Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), also known as South American blastomycosis, is a fungal infection that can occur as a mouth and skin type, lymphangitic type, multi-organ involvement type (particularly lungs), or mixed type.[1][6] If there are mouth ulcers or skin lesions, the disease is likely to be widespread.[1] There may be no symptoms, or it may present with fever, sepsis, weight loss, large glands, or a large liver and spleen.[4][7]

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | South American blastomycosis,[1] Brazilian blastomycosis,[2] Lutz-Splendore-de Almeida disease,[3] |

| |

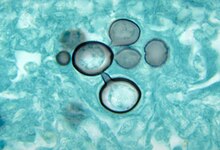

| Paracoccidioides histopathology | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, sepsis, weight loss, large glands, large liver and spleen,[4] mouth ulcers, skin lesions.[5] |

| Types | Mucocutaneous, lymphatic, multi-organ[1] |

| Causes | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Sampling of blood, sputum, or skin[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Tuberculosis, leukaemia, lymphoma[4] |

| Treatment | Antifungal medication[6] |

| Medication | Itraconazole, amphotericin B,[6] trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole[7] |

| Deaths | 200 deaths per year in Brazil[1] |

The cause is fungi in the genus Paracoccidioides, including Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii,[8] acquired by breathing in fungal spores.[6]

Diagnosis is by sampling of blood, sputum, or skin.[4] The disease can appear similar to tuberculosis, leukaemia, and lymphoma[4] Treatment is with antifungals; itraconazole.[1][7] For severe disease, treatment is with amphotericin B followed by itraconazole, or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as an alternative.[1][7]

It is endemic to Central and South America,[9] and is considered a type of neglected tropical disease.[8] In Brazil, the disease causes around 200 deaths per year.[1]

Signs and symptoms

editAsymptomatic lung infection is common, with fewer than 5% of infected individuals developing clinical disease.[10]

It can occur as a mouth and skin type, lymphangitic type, multi-organ involvement type (particularly lungs), or mixed type.[1][6] If there are mouth ulcers or skin lesions, the disease is likely to be widespread.[1] There may be no symptoms, or it may present with fever, sepsis, weight loss, large glands, or a large liver and spleen.[4][7]

Two presentations are known, firstly the acute or subacute form, which predominantly affects children and young adults,[11] and the chronic form, predominantly affecting adult men.[12] Most cases are infected before age 20, although symptoms may present many years later.[13]

Juvenile (acute/subacute) form

editThe juvenile, acute form is characterised by symptoms, such as fever, weight loss and feeling unwell together with enlarged lymph nodes and enlargement of the liver and spleen.[14][15][16] This form is most often disseminated, with symptoms manifesting depending on the organs involved.[14] Skin and mucous membrane lesions are often present,[17] and bone involvement may occur in severe cases.[14] This acute, severe presentation may mimic tuberculosis, lymphoma or leukaemia.[17]

Adult (chronic) form

editThe chronic form presents months to years after the initial infection occurs and most frequently presents with dry cough and shortness of breath.[10] Other symptoms include excess salivation, difficulty swallowing, and difficulties with voice control.[14] Upper respiratory tract mucosal lesions may be present, as well as increased mucus production and coughing up blood.[18] Both pulmonary and extrapulmonary involvement is common.[14]

Up to 70% of cases have mucosal involvement, with lesions often found in the mouth, oropharynx, larynx, and palate. Classic lesions are superficial painful granular ulcers, with small spots of bleeding.[15]

Cause

editParacoccidioidomycosis is caused by two species of fungi that can exist as a mold or yeast depending on temperature, P. brasiliensis and P. lutzii.[19] In protected soil environments, near water sources, that are disturbed either naturally or by human activity, P. brasiliensis has been epidemiologically observed (although not isolated).[20] A known animal carrier is the armadillo.[13] In the natural environment, the fungi are found as filamentous structures, and they develop infectious spores known as conidia.[13]

Human to human transmission has never been proven.[21]

Mechanism

editPrimary infection, although poorly understood due to lack of data, is thought to occur through inhalation of the conidia through the respiratory tract, after inhaling fungal conidia produced by the mycelial form of P. brasiliensis.[14][21] This occurs predominantly in childhood and young adulthood, after exposure to agricultural activity.[13] Infection may occur through direct skin inoculation, although this is rare.[15]

After inhalation into the alveoli, there is rapid multiplication of the organism in the lung tissue, sometimes spreading via the venous and lymphatic systems.[14] Approximately 2% of people develop clinical features after the initial asymptomatic infection.[15]

The type of immune response determines the clinical manifestation of the infection, with children and HIV co-infected individuals most commonly developing the acute/subacute disseminated disease.[14] Most of those infected develop a Type 1 T-cell (Th1) mediated immune response, resulting in fibrosing alveolitis and compact granuloma formation that control fungal replication, and latent or asymptomatic infection.[13][14] It then is thought to remain dormant in residual lung lesions and mediastinal lymph nodes.[21] A deficient Th1 cell response results in the severe forms of the disease. In these individuals, granulomas do not form, and the affected person develops Th2 and Th9 responses, resulting in activation of B lymphocytes, high levels of circulating antibodies, eosinophilia, and hypergammaglobulinemia.[13]

Lung involvement subsequently occurs after a dormant phase, manifesting in upper respiratory tract symptoms, and lung infiltrates on imaging.[15] The commonest, chronic form, is almost certainly a reactivation of the disease,[15] and may develop into progressive scarring of the lungs (pulmonary fibrosis).[22]

It can cause disease in those with normal immune function, although immunosuppression increases the aggressiveness of the fungus. It rarely causes disease in fertile-age women, probably due to a protective effect of estradiol.[23]

Diagnosis

editMore than 90% of cases can be diagnoses with direct histological examination of tissue, such as sputum, bronchial lavage fluid, exudates and biopsies. Histopathological study with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain revealing large yeast cells with translucent cell walls with multiple buds.[14]

In the juvenile form, lung abnormalities are shown in high-resolution CT scans of the lungs, whereas in the chronic form plain X-rays may show interstitial and alveolar infiltrates in the central and lower lung fields.[14]

Culture of P. brasiliensis takes between 20 and 30 days, requiring multiple samples and culture media. Initial culture can occur at room temperature, however after growth is noted, confirmation occurs by incubating at to 36-37 degrees to transform the fungus into yeast cells.[14]

Antibody detection is useful both for acute diagnosis and monitoring. Gel immunodiffusion is commonly used in endemic areas, diagnoses 95% of cases with high specificity.[14] Complement fixation allows for a measure of severity of cases by quantifying the antibody level, and is thus useful for monitoring treatment response. It is however only sensitive for 85% of cases, and cross-reacts with H. capsulatum.[14]

Differential diagnosis

editThe disease can appear similar to tuberculosis, leukaemia, and lymphoma[4]

Treatment

editBoth P. brasiliensis and P. lutzii are in-vitro susceptible to most antifungal agents, unlike other systemic fungal infections. Mild and moderate forms are treated with itraconazole for 9 to 18 months, as this has been shown to be more effective, has a shorter treatment duration and is more tolerated.[citation needed] Acidic beverages have been shown to reduce absorption of itraconazole.[13] Co-trimoxazole is a second line agent, and is preferred for those with brain involvement, and during pregnancy.[13] For severe cases, intravenous treatment with amphotericin B is indicated, for an average of 2 to 4 weeks.[13]Prednisolone prescribed at the same time may reduce inflammation during treatment.[13] Patients should be treated until stabilisation of symptoms, and increase in body weight. Advice in regards to nutritional support, as well as smoking and alcohol intake should be provided. Adrenal insufficiency, if found, is treated with corticosteroids.[24] Clinical criteria for cure includes the absence or healing of lesions, stabilisation of body weight, negative as well as negative autoantibody tests.[13] There is insufficient data to support the benefits of above drugs to treat the disease.[25]

Epidemiology

editParacoccidioidomycosis is endemic in rural areas of Latin America, from southern Mexico to Argentina, and is also found in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Paraguay.[13][15] An epidemic outbreak has never been observed.[13] It has the highest prevalence of all systemic mycoses (fungal infections) in the area.[12] As many as 75% of people in endemic areas have been estimated to be infected with the asymptomatic form (up to 10 million people), with 2% developing clinically significant disease.[12] Morbidity and mortality is strongly associated with patient's socioeconomic background,[12] with most adult patients being male agricultural workers.[26] Other risk factors include smoking, alcohol use, HIV co-infection or other immunosuppression.[21] 80% of reported cases are in Brazil, in the southeast, midwest, and south, spreading in the 1990s to the Amazon area. Most of the remaining infections are in Argentina, Colombia and Venezuela.[21] Most epidemiological reports have focused on P. brasliensis, with P. lutzii epidemiology poorly understood as of 2015.[21]

Rising cases have been linked to agriculturalization and deforestation in Brazil, urbanisation to peripheral city areas with poor infrastructure, as well as increased soil and air humidity.[13][21] One Brazilian indigenous tribe, the Surui, after changing from subsistence agriculture to coffee farming showed higher infection rates than surrounding tribes.[21]

There have also been reports in non-endemic areas with the rise of eco-tourism, in the United States, Europe and Japan.[15] All reported cases were returned travellers from endemic regions.[21]

History

editLutz-Splendore-de Almeida disease[3] is named for the physicians Adolfo Lutz,[27] Alfonso Splendore (1871–1953), an Italo-Brazilian parasitologist[28] and Floriano Paulo de Almeida (1898–1977), a Brazilian pathologist specializing in Pathologic Mycology (Study of Infectious Fungi),[29][30] who first characterized the disease in Brazil in the early 20th century.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2019). "13. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 313–314. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6.

- ^ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007), Dermatology: 2-Volume Set, St. Louis: Mosby, ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1

- ^ a b Lutz-Splendore-de Almeida disease at Who Named It?

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0.

- ^ a b c d e Barlow, Gavin; Irving, Irving; moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious diseases". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5.

- ^ a b c d e Proia, Laurie (2020). "28. The dimorphic mycoses". In Spec, Andrej; Escota, Gerome V.; Chrisler, Courtney; Davies, Bethany (eds.). Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 419–420. ISBN 978-0-323-56866-1.

- ^ a b Queiroz-Telles, Flavio; Fahal, Ahmed Hassan; Falci, Diego R; Caceres, Diego H; Chiller, Tom; Pasqualotto, Alessandro C (November 2017). "Neglected endemic mycoses". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (11): e367–e377. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30306-7. PMID 28774696.(subscription required)

- ^ Marques, Silvio Alencar (October 2013). "Paracoccidioidomycosis: epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic and treatment up-dating". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 88 (5): 700–711. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132463. ISSN 0365-0596. PMC 3798345. PMID 24173174.

- ^ a b Queiroz-Telles, Flavio; Escuissato, Dante (December 2011). "Pulmonary Paracoccidioidomycosis". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 32 (6): 764–774. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1295724. ISSN 1069-3424. PMID 22167404. S2CID 260319905.

- ^ Brummer, E; Castaneda, E; Restrepo, A (April 1993). "Paracoccidioidomycosis: an update". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 6 (2): 89–117. doi:10.1128/CMR.6.2.89. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 358272. PMID 8472249.

- ^ a b c d Travassos, Luiz R; Taborda, Carlos P; Colombo, Arnaldo L (April 2008). "Treatment options for paracoccidioidomycosis and new strategies investigated". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 6 (2): 251–262. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.2.251. ISSN 1478-7210. PMID 18380607. S2CID 41184245.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Shikanai-Yasuda, Maria Aparecida; Mendes, Rinaldo Pôncio; Colombo, Arnaldo Lopes; Queiroz-Telles, Flávio de; Kono, Adriana Satie Gonçalves; Paniago, Anamaria M. M; Nathan, André; Valle, Antonio Carlos Francisconi do; Bagagli, Eduardo (2017-07-12). "Brazilian guidelines for the clinical management of paracoccidioidomycosis". Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 50 (5): 715–740. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0230-2017. hdl:11449/163455. ISSN 1678-9849. PMID 28746570.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Restrepo, Angela M.; Tobón Orozco, Angela Maria; Gómez, Beatriz L.; Benard, Gil (2015), Hospenthal, Duane R.; Rinaldi, Michael G. (eds.), "Paracoccidioidomycosis", Diagnosis and Treatment of Fungal Infections, Infectious Disease, Springer International Publishing, pp. 225–236, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13090-3_19, ISBN 9783319130903, S2CID 243500706

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marques, SA (Nov–Dec 2012). "Paracoccidioidomycosis". Clinics in Dermatology. 30 (6): 610–5. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2012.01.006. PMID 23068148.

- ^ F. Franco, Marcello; Del Negro, Gildo; Lacaz, Carlos da Silva; Restrepo-Moreno, Angela (1994). Paracoccidioidomycosis. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 9780849348686. OCLC 28421361.

- ^ a b Ferreira, Marcelo Simão (2009-12-01). "Paracoccidioidomycosis". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 10 (4): 161–165. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2009.08.001. ISSN 1526-0542. PMID 19879504.

- ^ RESTREPO, ANGELA; TOBÓN, ANGELA MARÍA (2010), "Paracoccidioides brasiliensis", Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, Elsevier, pp. 3357–3363, doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-06839-3.00268-x, ISBN 9780443068393

- ^ Salgado-Salazar, Catalina; Jones, Leandro R.; Restrepo, Ángela; McEwen, Juan G. (2010-11-10). "The human fungal pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Onygenales: Ajellomycetaceae) is a complex of two species: phylogenetic evidence from five mitochondrial markers". Cladistics. 26 (2010): 613–624. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00307.x. hdl:11336/84231. ISSN 1096-0031. PMID 34879597. S2CID 84410217.

- ^ Felipe, Maria S. S.; Bagagli, Eduardo; Nino-Vega, Gustavo; Theodoro, Raquel C.; Teixeira, Marcus M. (2014-10-30). "Paracoccidioides Species Complex: Ecology, Phylogeny, Sexual Reproduction, and Virulence". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (10): e1004397. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004397. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 4214758. PMID 25357210.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Martinez, Roberto (September 2015). "Epidemiology of Paracoccidioidomycosis". Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 57 (suppl 19): 11–20. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652015000700004. ISSN 0036-4665. PMC 4711199. PMID 26465364.

- ^ Kasper, Dennis L.; Fauci, Anthony S.; Hauser, Stephen L.; Longo, Dan L.; Larry Jameson, J.; Loscalzo, Joseph (2018-02-06). "Superficial Mycoses and Less Common Systemic Mycoses". Harrison's principles of internal medicine. Jameson, J. Larry,, Kasper, Dennis L.,, Fauci, Anthony S., 1940-, Hauser, Stephen L.,, Longo, Dan L. (Dan Louis), 1949-, Loscalzo, Joseph (Twentieth ed.). New York. ISBN 9781259644047. OCLC 990065894.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Severo LC, Roesch EW, Oliveira EA, Rocha MM, Londero AT (June 1998), "Paracoccidioidomycosis in women", Rev Iberoam Micol, 15 (2): 88–9, PMID 17655417.

- ^ Shikanai-Yasuda, Maria Aparecida (September 2015). "Paracoccidioidomycosis Treatment". Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 57 (Suppl 19): 31–37. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652015000700007. PMC 4711189. PMID 26465367.

- ^ da Mota Menezes, Valfredo; Soares, Bernardo GO; Fontes, Cor Jesus Fernandes (2006-04-19). Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (ed.). "Drugs for treating paracoccidioidomycosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (2): CD004967. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004967.pub2. PMC 6532700. PMID 16625617.

- ^ Restrepo, Angela; Tobón, Angela M.; Agudelo, Carlos A. (2008), "Paracoccidioidomycosis", Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Mycoses, Infectious Disease, Humana Press, pp. 331–342, doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-325-7_18, ISBN 9781588298225

- ^ Lutz A (1908), "Uma mycose pseudococcidioidica localizada no boca e observada no Brasil. Contribuicao ao conhecimento das hypoblastomycoses americanas.", Imprensa Médica (in Portuguese), 16, Rio de Janeiro: 151–163

- ^ Splendore A (1912), "Zimonematosi con localizzazione nella cavita della bocca osservata nel Brasile", Bulletin de la Société de pathologie exotique (in French), 5, Paris: 313–319

- ^ De Almeida FP (1928), "Lesoes cutaneas da blastomicose en cabaios experimentalmente infeetados", Anais da Faculdade de Medicina de Universidade de São Paulo (in Portuguese), 3: 59–64

- ^ de Almeida FP, da Silva Lacaz C (1942), "Micoses broco-pulmonares", Comp. Melhoramentos (in Portuguese), São Paulo: 98 pages