A lymph node, or lymph gland,[1] is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that include B and T cells. Lymph nodes are important for the proper functioning of the immune system, acting as filters for foreign particles including cancer cells, but have no detoxification function.

| Lymph node | |

|---|---|

Diagram showing major parts of a lymph node | |

Lymph nodes form part of the lymphatic system, and are present in most parts of the body, and connected by small lymphatic vessels. | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system, part of the immune system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nodus lymphaticus (singular); nodi lymphatici (plural) |

| MeSH | D008198 |

| TA98 | A13.2.03.001 |

| TA2 | 5192 |

| FMA | 5034 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In the lymphatic system, a lymph node is a secondary lymphoid organ. A lymph node is enclosed in a fibrous capsule and is made up of an outer cortex and an inner medulla.

Lymph nodes become inflamed or enlarged in various diseases, which may range from trivial throat infections to life-threatening cancers. The condition of lymph nodes is very important in cancer staging, which decides the treatment to be used and determines the prognosis. Lymphadenopathy refers to glands that are enlarged or swollen. When inflamed or enlarged, lymph nodes can be firm or tender.

Structure

editLymph nodes are kidney or oval shaped and range in size from 2 mm to 25 mm on their long axis, with an average of 15 mm.[2]

Each lymph node is surrounded by a fibrous capsule, which extends inside a lymph node to form trabeculae.[3] The substance of a lymph node is divided into the outer cortex and the inner medulla.[3] These are rich with cells.[4] The hilum is an indent on the concave surface of the lymph node where lymphatic vessels leave and blood vessels enter and leave.[4]

Lymph enters the convex side of a lymph node through multiple afferent lymphatic vessels and from there flows into a series of sinuses.[3] After entering the lymph node from afferent lymphatic vessels, lymph flows into a space underneath the capsule called the subcapsular sinus, then into cortical sinuses.[3] After passing through the cortex, lymph then collects in medullary sinuses.[3] All of these sinuses drain into the efferent lymph vessels to exit the node at the hilum on the concave side.[3]

Location

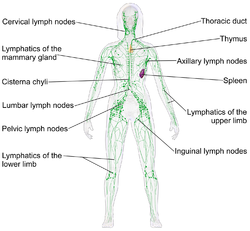

editLymph nodes are present throughout the body, are more concentrated near and within the trunk, and are divided into groups.[4] There are about 450 lymph nodes in the adult.[4] Some lymph nodes can be felt when enlarged (and occasionally when not), such as the axillary lymph nodes under the arm, the cervical lymph nodes of the head and neck and the inguinal lymph nodes near the groin crease. Most lymph nodes lie within the trunk adjacent to other major structures in the body - such as the paraaortic lymph nodes and the tracheobronchial lymph nodes. The lymphatic drainage patterns are different from person to person and even asymmetrical on each side of the same body.[5][6]

There are no lymph nodes in the central nervous system, which is separated from the body by the blood–brain barrier. Lymph from the meningeal lymphatic vessels in the CNS drains to the deep cervical lymph nodes.[7] However, the CNS does innervate lymph node by sympathetic nerves. These regulate lymphocyte proliferation and migration, antibody secretion, blood perfusion, and inflammatory cytokine production.[8]

Size

edit| Generally | 10 mm[9][10] |

| Inguinal | 10[11] – 20 mm[12] |

| Pelvis | 10 mm for ovoid lymph nodes, 8 mm for rounded[11] |

| Neck | |

|---|---|

| Generally (non-retropharyngeal) | 10 mm[11][13] |

| Jugulodigastric lymph nodes | 11mm[11] or 15 mm[13] |

| Retropharyngeal | 8 mm[13]

|

| Mediastinum | |

| Mediastinum, generally | 10 mm[11] |

| Superior mediastinum and high paratracheal | 7mm[14] |

| Low paratracheal and subcarinal | 11 mm[14] |

| Upper abdominal | |

| Retrocrural space | 6 mm[15] |

| Paracardiac | 8 mm[15] |

| Gastrohepatic ligament | 8 mm[15] |

| Upper paraaortic region | 9 mm[15] |

| Portacaval space | 10 mm[15] |

| Porta hepatis | 7 mm[15] |

| Lower paraaortic region | 11 mm[15] |

Subdivisions

editA lymph node is divided into compartments called nodules (or lobules), each consisting of a region of cortex with combined follicle B cells, a paracortex of T cells, and a part of the nodule in the medulla.[16] The substance of a lymph node is divided into the outer cortex and the inner medulla.[3] The cortex of a lymph node is the outer portion of the node, underneath the capsule and the subcapsular sinus.[16] It has an outer part and a deeper part known as the paracortex.[16] The outer cortex consists of groups of mainly inactivated B cells called follicles.[4] When activated, these may develop into what is called a germinal centre.[4] The deeper paracortex mainly consists of the T cells.[4] Here the T-cells mainly interact with dendritic cells, and the reticular network is dense.[17]

The medulla contains large blood vessels, sinuses and medullary cords that contain antibody-secreting plasma cells. There are fewer cells in the medulla.[4]

The medullary cords are cords of lymphatic tissue, and include plasma cells, macrophages, and B cells.

Cells

editIn the lymphatic system a lymph node is a secondary lymphoid organ.[4] Lymph nodes contain lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, and are primarily made up of B cells and T cells.[4] B cells are mainly found in the outer cortex where they are clustered together as follicular B cells in lymphoid follicles, and T cells and dendritic cells are mainly found in the paracortex.[18]

There are fewer cells in the medulla than the cortex.[4] The medulla contains plasma cells, as well as macrophages which are present within the medullary sinuses.[18]

As part of the reticular network, there are follicular dendritic cells in the B cell follicle and fibroblastic reticular cells in the T cell cortex. The reticular network provides structural support and a surface for adhesion of the dendritic cells, macrophages and lymphocytes. It also allows exchange of material with blood through the high endothelial venules and provides the growth and regulatory factors necessary for activation and maturation of immune cells.[19]

Lymph flow

editLymph enters the convex side of a lymph node through multiple afferent lymphatic vessels, which form a network of lymphatic vessels (Latin: plexus) and flows into a space (Latin: sinus) underneath the capsule called the subcapsular sinus.[4][3] From here, lymph flows into sinuses within the cortex.[3] After passing through the cortex, lymph then collects in medullary sinuses.[3] All of these sinuses drain into the efferent lymphatic vessels to exit the node at the hilum on the concave side.[3]

These are channels within the node lined by endothelial cells along with fibroblastic reticular cells, allowing for the smooth flow of lymph. The endothelium of the subcapsular sinus is continuous with that of the afferent lymph vessel and also with that of the similar sinuses flanking the trabeculae and within the cortex. These vessels are smaller and do not allow the passage of macrophages so that they remain contained to function within a lymph node. In the course of the lymph, lymphocytes may be activated as part of the adaptive immune response.

There is usually only one efferent vessel though sometimes there may be two, in contrast to the multiple afferent channels that bring lymph into the node.[20] Medullary sinuses contain histiocytes (immobile macrophages) and reticular cells, the former of which, along with T and B cells, become activated in the presence of antigens through lymphatic flow. The fewer efferent vessels allow this flow to be slowed, providing time to activate and distribute a larger number of immune cells in the event of an infection.

A lymph node contains lymphoid tissue, i.e., a meshwork or fibers called reticulum with white blood cells enmeshed in it. The regions where there are few cells within the meshwork are known as lymph sinus. It is lined by reticular cells, fibroblasts and fixed macrophages.[21]

Capsule

editThin reticular fibers (reticulin) of reticular connective tissue form a supporting meshwork inside the node.[4] These reticular cells also form a conduit network within the lymph node that functions as a molecular sieve, to prevent pathogens that enter the lymph node through afferent vessels re-enter the blood stream.[22] The lymph node capsule is composed of dense irregular connective tissue with some plain collagenous fibers, and a number of membranous processes or trabeculae extend from its internal surface. The trabeculae pass inward, radiating toward the center of the node, for about one-third or one-fourth of the space between the circumference and the center of the node. In some animals they are sufficiently well-marked to divide the peripheral or cortical portion of the node into a number of compartments (nodules), but in humans this arrangement is not obvious. The larger trabeculae springing from the capsule break up into finer bands, and these interlace to form a mesh-work in the central or medullary portion of the node. These trabecular spaces formed by the interlacing trabeculae contain the proper lymph node substance or lymphoid tissue. The node pulp does not, however, completely fill the spaces, but leaves between its outer margin and the enclosing trabeculae a channel or space of uniform width throughout. This is termed the subcapsular sinus (lymph path or lymph sinus). Running across it are a number of finer trabeculae of reticular fibers, mostly covered by ramifying cells.

Function

editIn the lymphatic system, a lymph node is a secondary lymphoid organ.[4]

The primary function of lymph nodes is the filtering of lymph to identify and fight infection. In order to do this, lymph nodes contain lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, which includes B cells and T cells. These circulate through the bloodstream and enter and reside in lymph nodes.[23] B cells produce antibodies. Each antibody has a single predetermined target, an antigen, that it can bind to. These circulate throughout the bloodstream and if they find this target, the antibodies bind to it and stimulate an immune response. Each B cell produces different antibodies, and this process is driven in lymph nodes. B cells enter the bloodstream as "naive" cells produced in bone marrow. After entering a lymph node, they then enter a lymphoid follicle, where they multiply and divide, each producing a different antibody. If a cell is stimulated, it will go on to produce more antibodies (a plasma cell) or act as a memory cell to help the body fight future infection.[24] If a cell is not stimulated, it will undergo apoptosis and die.[24]

Antigens are molecules found on bacterial cell walls, chemical substances secreted from bacteria, or sometimes even molecules present in body tissue itself. These are taken up by cells throughout the body called antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells.[25] These antigen presenting cells enter the lymph system and then lymph nodes. They present the antigen to T cells and, if there is a T cell with the appropriate T cell receptor, it will be activated.[24]

B cells acquire antigen directly from the afferent lymph. If a B cell binds its cognate antigen it will be activated. Some B cells will immediately develop into antibody secreting plasma cells, and secrete IgM. Other B cells will internalize the antigen and present it to follicular helper T cells on the B and T cell zone interface. If a cognate FTh cell is found it will upregulate CD40L and promote somatic hypermutation and isotype class switching of the B cell, increasing its antigen binding affinity and changing its effector function. Proliferation of cells within a lymph node will make the node expand.

Lymph is present throughout the body, and circulates through lymphatic vessels. These drain into and from lymph nodes – afferent vessels drain into nodes, and efferent vessels from nodes. When lymph fluid enters a node, it drains into the node just beneath the capsule in a space called the subcapsular sinus. The subcapsular sinus drains into trabecular sinuses and finally into medullary sinuses. The sinus space is criss-crossed by the pseudopods of macrophages, which act to trap foreign particles and filter the lymph. The medullary sinuses converge at the hilum and lymph then leaves the lymph node via the efferent lymphatic vessel towards either a more central lymph node or ultimately for drainage into a central venous subclavian blood vessel.

- The B cells migrate to the nodular cortex and medulla.

- The T cells migrate to the deep cortex. This is a region of a lymph node called the paracortex that immediately surrounds the medulla. Because both naive T cells and dendritic cells express CCR7, they are drawn into the paracortex by the same chemotactic factors, increasing the chance of T cell activation. Both B and T lymphocytes enter lymph nodes from circulating blood through specialized high endothelial venules found in the paracortex.

Clinical significance

editSwelling

editLymph node enlargement or swelling is known as lymphadenopathy.[26] Swelling may be due to many causes, including infections, tumors, autoimmune disease, drug reactions, diseases such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis, or because of lymphoma or leukemia.[27][26] Depending on the cause, swelling may be painful, particularly if the expansion is rapid and due to an infection or inflammation.[26] Lymph node enlargement may be localized to an area, which might suggest a local source of infection or a tumour in that area that has spread to the lymph node.[26] It may also be generalized, which might suggest infection, connective tissue or autoimmune disease, or a malignancy of blood cells such as a lymphoma or leukemia.[26] Rarely, depending on location, lymph node enlargement may cause problems such as difficulty breathing, or compression of a blood vessel (for example, superior vena cava obstruction[28]).

Enlarged lymph nodes might be felt as part of a medical examination, or found on medical imaging.[29] Features of the medical history may point to the cause, such as the speed of onset of swelling, pain, and other constitutional symptoms such as fevers or weight loss.[30] For example, a tumour of the breast may result in swelling of the lymph nodes under the arms[26] and weight loss and night sweats may suggest a malignancy such as lymphoma.[26]

In addition to a medical exam by a medical practitioner, medical tests may include blood tests and scans may be needed to further examine the cause.[26] A biopsy of a lymph node may also be needed.[26]

Cancer

editLymph nodes can be affected by both primary cancers of lymph tissue, and secondary cancers affecting other parts of the body. Primary cancers of lymph tissue are called lymphomas and include Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[31] Cancer of lymph nodes can cause a wide range of symptoms from painless long-term slowly growing swelling to sudden, rapid enlargement over days or weeks, with symptoms depending on the grade of the tumour.[31] Most lymphomas are tumours of B-cells.[31] Lymphoma is managed by haematologists and oncologists.

Local cancer in many parts of the body can cause lymph nodes to enlarge because of tumorous cells that have metastasised into the node.[32] Lymph node involvement is often a key part in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, acting as "sentinels" of local disease, incorporated into TNM staging and other cancer staging systems. As part of the investigations or workup for cancer, lymph nodes may be imaged or even surgically removed. If removed, the lymph node will be stained and examined under a microscope by a pathologist to determine if there is evidence of cells that appear cancerous (i.e. have metastasized into the node). The staging of the cancer, and therefore the treatment approach and prognosis, is predicated on the presence of node metastases.

Lymphedema

editLymphedema is the condition of swelling (edema) of tissue relating to insufficient clearance by the lymphatic system.[33] It can be congenital as a result usually of undeveloped or absent lymph nodes, and is known as primary lymphedema. Lymphedema most commonly arises in the arms or legs, but can also occur in the chest wall, genitals, neck, and abdomen.[34] Secondary lymphedema usually results from the removal of lymph nodes during breast cancer surgery or from other damaging treatments such as radiation. It can also be caused by some parasitic infections. Affected tissues are at a great risk of infection.[citation needed] Management of lymphedema may include advice to lose weight, exercise, keep the affected limb moist, and compress the affected area.[33] Sometimes surgical management is also considered.[33]

Similar lymphoid organs

editThe spleen and the tonsils are the larger secondary lymphoid organs that serve somewhat similar functions to lymph nodes, though the spleen filters blood cells rather than lymph. The tonsils are sometimes erroneously referred to as lymph nodes. Although the tonsils and lymph nodes do share certain characteristics, there are also many important differences between them, such as their location, structure and size.[35] Furthermore, the tonsils filter tissue fluid whereas lymph nodes filter lymph.[35]

The appendix contains lymphoid tissue and is therefore believed to play a role not only in the digestive system, but also in the immune system.[36]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Swollen glands NHS inform". www.nhsinform.scot. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Ioachim, Harry L. (1994). Lymph Node Pathology (Second ed.). J. B. Lippincott Company. p. 3. ISBN 9780397508075. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Young B, O'Dowd G, Woodford P (2013). Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 209–210. ISBN 9780702047473.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). "Lymphoid tissues". Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 73–4. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Themes, U. F. O. (6 January 2018). "Lymphatic Anatomy and Clinical Implications". Ento Key. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Pan, Wei-Ren; Wang, De-Guang (2013). "Historical review of lymphatic studies in the head and neck" (PDF). Journal of Lymphoedema. 8. WoundsGroup. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Dupont G, Schmidt C, Yilmaz E, Oskouian RJ, Macchi V, de Caro R, Tubbs RS (January 2019). "Our current understanding of the lymphatics of the brain and spinal cord". Clinical Anatomy. 32 (1): 117–121. doi:10.1002/ca.23308. PMID 30362622. S2CID 53102520.

- ^ Cleypool, Cindy G. J.; Mackaaij, Claire; Lotgerink Bruinenberg, Dyonne; Schurink, Bernadette; Bleys, Ronald L. A. W. (2021). "Sympathetic nerve distribution in human lymph nodes". Journal of Anatomy. 239 (2). Wiley: 282–289. doi:10.1111/joa.13422. ISSN 0021-8782.

- ^ Ganeshalingam, Skandadas; Koh, Dow-Mu (2009). "Nodal staging". Cancer Imaging. 9 (1): 104–111. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2009.0017. ISSN 1470-7330. PMC 2821588. PMID 20080453.

- ^ Schmidt Júnior, Aurelino Fernandes; Rodrigues, Olavo Ribeiro; Matheus, Roberto Storte; Kim, Jorge Du Ub; Jatene, Fábio Biscegli (2007). "Distribuição, tamanho e número dos linfonodos mediastinais: definições por meio de estudo anatômico". Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 33 (2): 134–140. doi:10.1590/S1806-37132007000200006. ISSN 1806-3713. PMID 17724531.

- ^ a b c d e f Torabi M, Aquino SL, Harisinghani MG (September 2004). "Current concepts in lymph node imaging". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 45 (9): 1509–18. PMID 15347718.

- ^ "Assessment of lymphadenopathy". BMJ Best Practice. Retrieved 4 March 2017. Last updated: Last updated: Feb 16, 2017

- ^ a b c Page 432 in: Luca Saba (2016). Image Principles, Neck, and the Brain. CRC Press. ISBN 9781482216202.

- ^ a b Sharma, Amita; Fidias, Panos; Hayman, L. Anne; Loomis, Susanne L.; Taber, Katherine H.; Aquino, Suzanne L. (2004). "Patterns of Lymphadenopathy in Thoracic Malignancies". RadioGraphics. 24 (2): 419–434. doi:10.1148/rg.242035075. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 15026591. S2CID 7434544.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dorfman, R E; Alpern, M B; Gross, B H; Sandler, M A (1991). "Upper abdominal lymph nodes: criteria for normal size determined with CT". Radiology. 180 (2): 319–322. doi:10.1148/radiology.180.2.2068292. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 2068292.

- ^ a b c Willard-Mack CL (25 June 2016). "Normal structure, function, and histology of lymph nodes". Toxicologic Pathology. 34 (5): 409–24. doi:10.1080/01926230600867727. PMID 17067937.

- ^ Katakai T, Hara T, Lee JH, Gonda H, Sugai M, Shimizu A (August 2004). "A novel reticular stromal structure in lymph node cortex: an immuno-platform for interactions among dendritic cells, T cells and B cells". International Immunology. 16 (8): 1133–42. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxh113. PMID 15237106.

- ^ a b Davidson's 2018, p. 67.

- ^ Kaldjian EP, Gretz JE, Anderson AO, Shi Y, Shaw S (October 2001). "Spatial and molecular organization of lymph node T cell cortex: a labyrinthine cavity bounded by an epithelium-like monolayer of fibroblastic reticular cells anchored to basement membrane-like extracellular matrix". International Immunology. 13 (10): 1243–53. doi:10.1093/intimm/13.10.1243. PMID 11581169.

- ^ Henrikson RC, Mazurkiewicz JE (1 January 1997). Histology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780683062250.

- ^ Warwick R, Williams PL (1973) [1858]. "Angiology (Chapter 6)". Gray's anatomy. illustrated by Richard E. M. Moo re (Thirty-fifth ed.). London: Longman. pp. 588–785.

- ^ Roozendaal, Ramon (29 September 2008). "The conduit system of the lymph node". International Immunology. 20 (12): 1483–1487. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxn110. PMID 18824503. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Hoffbrand's 2016, p. 103,110.

- ^ a b c Hoffbrand's 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Hoffbrand's 2016, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Davidson's 2018, p. 927.

- ^ Hoffbrand's 2016, p. 114.

- ^ Davidson's 2018, p. 1326.

- ^ Gaddey, Heidi L.; Riegel, Angela M. (1 December 2016). "Unexplained Lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis". American Family Physician. 94 (11): 896–903. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 27929264.

- ^ Davidson's 2018, p. 913.

- ^ a b c Davidson's 2018, p. 961.

- ^ Davidson's 2018, p. 1324.

- ^ a b c Maclellan RA, Greene AK (August 2014). "Lymphedema". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 23 (4): 191–7. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.004. PMID 25241097.

- ^ "Lymphedema". MayoClinic.org. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b Lakna (31 January 2019). "What is the Difference Between Tonsils and Lymph Nodes". Pediaa.Com. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Kooij IA, Sahami S, Meijer SL, Buskens CJ, Te Velde AA (October 2016). "The immunology of the vermiform appendix: a review of the literature". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 186 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/cei.12821. PMC 5011360. PMID 27271818.

Bibliography

edit- Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MW, Hobson RP (2018). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

- Hoffbrand V, Moss PA (2016). Hoffbrand's essential haematology (7th ed.). West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-1184-0867-4.

External links

edit- Histology image: 07101loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Lymph Nodes

- Lymph Nodes Drainage

- An overview of Normal Lymph Nodes and Swollen lymph nodes and their evaluation