Parícutin (or Volcán de Parícutin, also accented Paricutín) is a cinder cone volcano located in the Mexican state of Michoacán, near the city of Uruapan and about 322 kilometers (200 mi) west of Mexico City. The volcano surged suddenly from the cornfield of local farmer Dionisio Pulido in 1943, attracting both popular and scientific attention.

| Parícutin | |

|---|---|

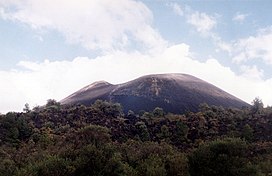

Parícutin in 1994 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,800 m (9,200 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 208 m (682 ft)[2] |

| Coordinates | 19°29′35″N 102°15′4″W / 19.49306°N 102.25111°W |

| Geography | |

| Country | Mexico |

| State | Michoacán |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | 1941–1952 |

| Mountain type | Cinder cone |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt |

| Last eruption | 1943 to 1952 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1943 |

| Easiest route | Hike |

Parícutin presented the first occasion for modern science to document the full life cycle of an eruption of this type. During the volcano's nine years of activity, scientists sketched and mapped it and took thousands of samples and photographs. By 1952, the eruption had left a 424-meter-high (1,391 ft) cone and significantly damaged an area of more than 233 square kilometers (90 sq mi) with the ejection of stone, volcanic ash and lava. Three people were killed, two towns were completely evacuated and buried by lava, and three others were heavily affected. Hundreds of people had to permanently relocate, and two new towns were created to accommodate their migration. Although the larger region still remains highly active volcanically, Parícutin is now dormant and has become a tourist attraction, with people climbing the volcano and visiting the hardened lava-covered ruins of the San Juan Parangaricutiro Church.

In 1997, CNN named Parícutin one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World.[3] The same year, the disaster film Volcano mentioned it as a precedent for the film's fictional events.

Description

editParícutin is located in the Mexican municipality of Nuevo Parangaricutiro, Michoacán, 29 kilometers (18 mi) west of the city of Uruapan and about 322 km west of Mexico City.[4][5][6] It lies on the northern flank of Pico de Tancítaro, which itself lies on top of an old shield volcano and extends 3,170 meters (10,400 ft) above sea level and 424 meters (1,391 ft) above the Valley of Quitzocho-Cuiyusuru.[6][7] These structures are wedged against old volcanic mountain chains and surrounded by small volcanic cones, with the intervening valleys occupied by small fields and orchards or small settlements, from groups of a few houses to those the size of towns.[6][7][8]

The volcano lies on, and is a product of, the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which runs 900 kilometers (560 mi) west-to-east across central Mexico. It includes the Sierra Nevada mountain range (a set of extinct volcanoes) as well as thousands of cinder cones and volcanic vents. Volcanic activity here has created the Central Mexican Plateau and rock deposits up to 1.8 kilometers (1.1 mi) deep. It has also created fertile soils by the widespread deposition of ash and thereby some of Mexico's most productive farmland.[9] The volcanic activity here is a result of the subduction of the Rivera and Cocos plates along the Middle America Trench.[10] More specifically, the volcano is the youngest of the approximately 1,400 volcanic vents of the Michoacán-Guanajuato volcanic field, a 40,000 square kilometers (15,000 sq mi) basalt plateau filled with scoria cones like Parícutin, along with small shield volcanoes, maars, tuff rings and lava domes.[10][11] Scoria cones are the most common type of volcano in Mexico, appearing suddenly and building a cone-shaped mountain with steep slopes before becoming extinct. Parícutin's immediate predecessor was El Jorullo, also in Michoacán, which erupted in 1759.[9][12]

By 2013, the crater of the volcano was about 200 meters (660 ft) across, and it was possible to both climb the volcano and walk around the entire perimeter.[8] Although classified as extinct by scientists, Parícutin is still hot, and seeping rainwater reacts with this heat so that the cone still emits steam in various streams.[8][13][14] The forces that created the volcano are still active. In 1997 there was a vigorous swarm of 230 earthquakes in the Parícutin area due to tectonic movement, with five above 3.9 on the moment magnitude scale.[10] There were also some reports of rumbling in 1995, and of black steam and rumbling in 1998.[14] In the summer of 2006, there was another major volcanic earthquake swarm, with over 300 located near the volcano, indicating magma movement, but with no eruption at Parícutin or elsewhere.[10]

Formation

editParícutin erupted from 1943 to 1952, unusually long for this type of volcano, and with several eruptive phases.[6][11] For weeks prior, residents of the area reported hearing noises similar to thunder but without clouds in the sky. This sound is consistent with deep earthquakes caused by the movement of magma.[4][11] A later study indicated that the eruption was preceded by 21 earthquakes over 3.2 in intensity starting five weeks before the eruption. One week prior to the eruption, newspapers reported 25–30 per day. The day before the eruption, the number was estimated at 300.[10]

The eruption began on February 20, 1943,[15] at about 4:00 pm local time. The center of the activity was a cornfield owned by Dionisio Pulido, near the town of Parícutin. During that day, he and his family had been working their land, clearing it to prepare for spring planting.[9] Suddenly the ground nearby swelled upward and formed a fissure between 2 and 2.5 meters across. They reported that they heard hissing sounds, and saw smoke which smelled like rotten eggs, indicating the presence of hydrogen sulfide. Within hours, the fissure would develop into a small crater.[4][11]

Pulido reported:

At 4 p.m., I left my wife to set fire to a pile of branches when I noticed that a crack, which was situated on one of the knolls of my farm, had opened . . . and I saw that it was a kind of fissure that had a depth of only half a meter. I set about to ignite the branches again when I felt a thunder, the trees trembled, and I turned to speak to Paula; and it was then I saw how, in the hole, the ground swelled and raised itself 2 or 2.5 meters high, and a kind of smoke or fine dust – grey, like ashes – began to rise up in a portion of the crack that I had not previously seen . . . Immediately more smoke began to rise with a hiss or whistle, loud and continuous; and there was a smell of sulfur.[11]

He tried to find his family and oxen but they had disappeared; so he rode his horse to town where he found his family and friends, happy to see him alive.[9] The volcano grew fast and furiously after this.[4] Celedonio Gutierrez, who witnessed the eruption on the first night, reported:

…when night began to fall, we heard noises like the surge of the sea, and red flames of fire rose into the darkened sky, some rising 800 meters or more into the air, that burst like golden marigolds, and a rain like fireworks fell to the ground.[4]

On that first day, the volcano had begun strombolian pyroclastic activity; and within 24 hours there was a scoria cone fifty meters high, created by the ejection of lapilli fragments up to the size of a walnut and larger, semi-molten volcanic bombs. By the end of the week, reports held that the cone was between 100 and 150 meters high.[4][9][11] Soon after the start, the valley was covered in smoke and ash.[4]

Phases

editThe nine-year activity of the volcano is divided into four stages, with names that come from the Purépecha language. The first phase (Quitzocho) extended from February 22 to October 18, 1943, with activity concentrated in the cracks that formed in the Cuiyusuro Valley, forming the initial cone. During this time, the ejected material was mostly lapilli and bombs.[6] In March, the eruption became more powerful, with eruptive columns that extended for several kilometers.[11] In four months, the cone reached 200 meters and in eight months 365 meters.[6] During this time period, there was some lava flow. On June 12, lava began to advance towards the village of Parícutin, forcing evacuations the next day.[11]

The second phase went from October 18, 1943 to January 8, 1944 and is called Sapichi, meaning "child", referring to the formation of a lateral vent and other openings on the north side of the cone.[6][8] Ash and bombs continued to be ejected but the new vent sent lava towards the town of San Juan Parangaricutiro, forcing its permanent evacuation. By August, the town was completely covered in lava and ash, with only the upper portions of the main church still visible.[6][11] The evacuations of Parícutin and San Juan were accomplished without loss of life due to the slow movement of the lava.[4][13] These two phases lasted just over a year and account for more than 90% of the total material ejected from the cone, as well as almost four-fifths (330 meters) of the final height of 424 meters from the valley floor. It also sent ash as far as Mexico City.[4][9]

The third (Taqué-Ahuan) lasted from January 8, 1944 to January 12, 1945 and featured mainly the formation of a series of cracks on the south side of the cone, as well as an increase in activity in the center. Lava flows from this time mostly extend to the west and northwest. During this period there also formed a mesa, now called Los Hornitos, to the south.[6]

Over the next seven years, the volcano became less active, with the ejection of ash, stone and lava coming sporadically, with periods of silence in between.[6][9][11] Professional geologists pulled out of the area in 1948, leaving only Celedonio Gutierrez to continue observations. The last burst of activity was recorded by him between January and February 1952. Several eruptions occurred in succession and a three-kilometer smoke column was produced.[6][9]

Scientific study

editThe particular importance of the Parícutin eruption was that it was the first time that volcanologists were able to fully document the entire life cycle of a volcano.[4][11] The event brought geologists from all over the world,[11] but the principal researchers were William F. Foshag of the Smithsonian Institution and Dr. Jenaro Gonzalez Reyna from the Mexican government, who came about a month after the eruption started and stayed for several years. These two wrote detailed descriptions, drew sketches and maps, and took samples and thousands of photographs during this time. Many of these are still used today by researchers. Foshag continued to study the volcano until his death in 1956.[4][9] Between 1943 and 1948, almost fifty scientific articles were published in major journals about the volcano, with even more since. The worldwide effort to study Parícutin increased understanding of volcanism in general but particularly that of scoria cone formation.[11][12]

Socioeconomic consequences

editDespite the ongoing Second World War, the eruption drew attention from around the world, with reporters from newspapers and magazines including Life coming to cover the story. In the later years of the eruption, airline pilots pointed the volcano out to passengers. The Hollywood film, Captain from Castile, was shot in the area, using the erupting volcano as a backdrop and employing locals as extras.[9] Some outdoor shots of the Western film, Garden of Evil , were filmed at the church ruins of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro and in the village of Guanajuato with the then unrestored church ruins of the Templo Santiago Apóstol, Marfil. The eruption also inspired a generation of Mexican artists to depict or allude to it in their works, including Dr Atl, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Alfredo Zalce and Pablo O'Higgins.[16]

The eruptions ended in 1952, leaving a final scoria cone with a height of 424 meters from the valley floor.[9][11] The eruption destroyed or heavily damaged a 233 km2 area,[7] and almost all of the vegetation within several kilometers of the crater was destroyed.[9] The volcano spread lava over 26 km2, with 52 km2 covered in volcanic sand.[9] The town of Parícutin, which once had a population of 733, is now completely gone, and all that remains of the town of San Juan Parangaricutiro, with a former population of 1,895, are parts of its main church which stand out among the hardened lava flow.[7][11][13]

Though no one died directly from the eruption, three people were killed when they were struck by lightning generated by pyroclastic eruptions.[11] The damage from the eruption primarily affected five towns in two municipalities, San Juan Parangaricutiro and Los Reyes. In addition to the two towns that were obliterated, Zacan (pop. 876), Angahuan (pop. 1,098) and Zirosto (pop. 1,314) were also heavily affected.[6] The main effect on the people of the area was the disruption of their lives and livelihood, especially during the first two years. The area most affected by the eruption had a population of 5,910,[7] and hundreds among these were permanently evacuated.[9] Before leaving his home for the last time, Dionisio Pulido placed a sign on the cornfield that read in Spanish: "This volcano is owned and operated by Dionisio Pulido."[9] The populations of the two destroyed towns were initially moved to camps on either side of the city of Uruapan.[7] The population of the other three towns mostly stayed in place, but made adaptations to survive during the eruption.[7] People of Angahuan and Zacan mostly stayed where they were.[7] The population of Zirosto divided into three: those that stayed in the original location, now known as Zirosto Viejo; those who moved a few miles away to a ranch which is now officially called Zirosto Nuevo but locally called Barranca Seca; and a third group who founded a completely new settlement called Miguel Silva near Ario de Rosales.[7]

The town of San Juan Parangaricutiro was the seat of the municipality of the same name, and its destruction prompted a political reorganization and a new seat at Parangaricutiro (today generally called San Juan Nuevo), where much of the population of the old seat had been relocated, with some going to Angahuan.[5][6][7]

The economy of the area was then and is now mostly agricultural, with a mostly Purépecha population, rural and poor.[6][8] However, the eruption did cause a number of changes both social and economic to the affected areas, both to adapt to the changed landscape but also because the fame of the eruption has brought greater contact from the rest of Mexico and beyond.[7]

The volcano has become a tourist attraction, with the main access in Angahuan, from which the volcano is clearly visible.[9] The town offers guides and horses, both to visit the ruins of the San Juan Parangaricutiro Church as well as to climb the volcano itself.[5] The volcano is part of the Pico de Tancítaro National Park and is mostly accessible on horseback, with only the last few hundred, very steep, meters to be climbed on foot.[13] The trek requires a guide even if horses are not used, as the path is not well-marked and passes through forest, agave fields and avocado groves. Many simply visit the ruins of the church, which are easier to access and still a pilgrimage site, the old altar regularly adorned with fresh candles and flowers. Nearby is a group of stands selling local food and souvenirs.[13]

The story of the formation of Parícutin is the subject of the children's book Hill of Fire by Thomas P. Lewis, published in 1983.[17] The book was featured in an episode of Reading Rainbow in 1985.[18]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Elevaciones principales – Michoacán de Ocampo" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. 2005. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ SRTM data

- ^ Alonso, Nathalie. "7 Natural Wonders of the World Today". USA Today Travel Tips. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Parícutin: The Birth of a Volcano". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Tips viajero Volcán Paricutín (Michoacán)". Mexico City: Mexico Desconocio magazine. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Volcanes Nombre del volcán: Paricutín". Instituto Latinoamericano de Comunicación Educativo. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nolan, Mary Lee (1972). The towns of the volcano: A study of the human consequences of the eruption of Parícutin Volcano (PhD). Texas A&M University. OCLC 7312281.

- ^ a b c d e Juan Guillermo Ordóñez (February 3, 2013). "Desafío Extremo / Aventura inolvidable en el Paricutín". El Norte. Monterrey. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Paricutin: The Volcano in a Cornfield". The Museum of Unnatural History. Archived from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Gardine, Matt; West, Michael E.; Cox, Tiffany (March 2011). "Dike emplacement near Paricutin volcano, Mexico in 2006". Bulletin of Volcanology. 73 (2): 123–132. Bibcode:2011BVol...73..123G. doi:10.1007/s00445-010-0437-9. S2CID 54179928.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "The eruption of Parícutin (1943–1952)". How Volcanos Work. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Antimio Cruz (February 20, 2003). "Niegan en Paricutin una nueva erupcion". Reforma. Mexico City. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e "Volcán Paricutín". Lonely Planet guides. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Adán García (December 5, 1998). "Chocan versiones sobre El Paricutin". Mural. Guadalajara. p. 10.

- ^ Foshag, William F. (1950). "The aqueous emanation from Paricutin volcano" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 35 (9 and 10): 749–755. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ Antimio Cruz (February 20, 2003). "'Multiplican' al Paricutin". Mural. Guadalajara. p. 5.

- ^ "Hill of Fire by Thomas P. Lewis | Scholastic". www.scholastic.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Burton, LeVar; Escandon, Fernando (July 3, 1985), Hill of Fire, archived from the original on February 21, 2017, retrieved February 20, 2017