The parietal bones (/pəˈraɪ.ɪtəl/ pə-RY-it-əl) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, and four angles. It is named from the Latin paries (-ietis), wall.

| Parietal bone | |

|---|---|

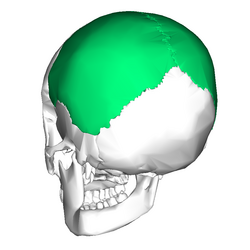

Position of the parietal bones | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | Five bones: the opposite parietal, the occipital, the frontal, the temporal, and the sphenoid |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os parietale |

| MeSH | D010294 |

| TA98 | A02.1.02.001 |

| TA2 | 504 |

| FMA | 9613 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Surfaces

editExternal

editThe external surface [Fig. 1] is convex, smooth, and marked near the center by an eminence, the parietal eminence (tuber parietale), which indicates the point where ossification commenced.

Crossing the middle of the bone in an arched direction are two curved lines, the superior and inferior temporal lines; the former gives attachment to the temporal fascia, and the latter indicates the upper limit of the muscular origin of the temporal muscle.

Above these lines the bone is covered by a tough layer of fibrous tissue – the epicranial aponeurosis; below them it forms part of the temporal fossa, and affords attachment to the temporal muscle.

At the back part and close to the upper or sagittal border is the parietal foramen which transmits a vein to the superior sagittal sinus, and sometimes a small branch of the occipital artery; it is not constantly present, and its size varies considerably.

Internal

editThe internal surface [Fig. 2] is concave; it presents depressions corresponding to the cerebral convolutions, and numerous furrows (grooves) for the ramifications of the middle meningeal artery; the latter run upward and backward from the sphenoidal angle, and from the central and posterior part of the squamous border.

Along the upper margin is a shallow groove, which, together with that on the opposite parietal, forms a channel, the sagittal sulcus, for the superior sagittal sinus; the edges of the sulcus afford attachment to the falx cerebri.

Near the groove are several depressions, best marked in the skulls of old persons, for the arachnoid granulations (Pacchionian bodies).

In the groove is the internal opening of the parietal foramen when that aperture exists.

Borders

edit- The sagittal border, the longest and thickest, is dentated (has toothlike projections) and articulates with its fellow of the opposite side, forming the sagittal suture.

- The frontal border is deeply serrated, and bevelled at the expense of the outer surface above and of the inner below; it articulates with the frontal bone, forming half of the coronal suture. The point where the coronal suture intersects with the sagittal suture forms a T-shape and is called the bregma.

- The squamous border is divided into three parts: of these:

- the anterior is thin and pointed, bevelled at the expense of the outer surface, and overlapped by the tip of the great wing of the sphenoid;

- the middle portion is arched, bevelled at the expense of the outer surface, and overlapped by the squama of the temporal;

- the posterior part is thick and serrated for articulation with the mastoid portion of the temporal.

- The occipital border, deeply denticulated (finely toothed), articulates with the occipital bone, forming half of the lambdoid suture. That point where the sagittal suture intersects the lambdoid suture is called the lambda, because of its resemblance to the Greek letter.

-

Skull seen from top. Sagittal suture separates left and right parietal bone.

-

Coronal suture. It separates the parietal bones and the frontal bone.

-

Squamosal suture. It separates the parietal bones and the temporal bone.

-

Lambdoid suture. It separates the parietal bones and the occipital bone.

Angles

edit- The frontal angle is practically a right angle, and corresponds with the point of meeting of the sagittal and coronal sutures; this point is named the bregma; in the fetal skull and for about a year and a half after birth this region is membranous, and is called the anterior fontanelle.

- The sphenoidal angle, thin and acute, is received into the interval between the frontal bone and the great wing of the sphenoid. Its inner surface is marked by a deep groove, sometimes a canal, for the anterior divisions of the middle meningeal artery.

- The occipital angle is rounded and corresponds with the point of meeting of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures—a point which is termed the lambda; in the fetus this part of the skull is membranous, and is called the posterior fontanelle.

- The mastoid angle is truncated; it articulates with the occipital bone and with the mastoid portion of the temporal, and presents on its inner surface a broad, shallow groove which lodges part of the transverse sinus. The point of meeting of this angle with the occipital and the mastoid part of the temporal is named the asterion.

Ossification

editThe parietal bone is ossified in membrane from a single center, which appears at the parietal eminence about the eighth week of fetal development.

Ossification gradually extends in a radial manner from the center toward the margins of the bone; the angles are consequently the parts last formed, and it is here that the fontanelles exist.

Occasionally the parietal bone is divided into two parts, upper and lower, by an antero-posterior suture.

In other animals

editIn non-human vertebrates, the parietal bones typically form the rear or central part of the skull roof, lying behind the frontal bones. In many non-mammalian tetrapods, they are bordered to the rear by a pair of postparietal bones that may be solely in the roof of the skull, or slope downwards to contribute to the back of the skull, depending on the species. In the living tuatara and some lizards, as well as in many fossil tetrapods, a small opening, the parietal foramen (also called the pineal foramen), is present between the two parietal bones at the midline of the skull. This opening is the location of the parietal eye (also called the pineal or third eye), which is much smaller than the two main eyes.[1][2][3]

In dinosaurs

editThe parietal bone is usually present in the posterior end of the skull and is near the midline. This bone is part of the skull roof, which is a set of bones that cover the brain, eyes and nostrils. The parietal bones make contact with several other bones in the skull. The anterior part of the bone articulates with the frontal bone and the postorbital bone. The posterior part of the bone articulates with the squamosal bone, and less commonly the supraoccipital bone. The bone-supported neck frills of ceratopsians were formed by extensions of the parietal bone. These frills, which overhang the neck and extend past the rest of the skull is a diagnostic trait of ceratopsians. The recognizable skull domes present in pachycephalosaurs were formed by the fusion of the frontal and parietal bones and the addition of thick deposits of bone to that unit.[4]

Additional images

edit-

Position of parietal bone (shown in green). Animation.

-

Parietal bone

-

Trajectory of the missile through President Kennedy's skull. The bullet struck posterior part of his right parietal bone from behind.

See also

editReferences

editThis article incorporates text in the public domain from page 133 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 217–244. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Benoit, Julien; Abdala, Fernando; Manger, Paul; Rubidge, Bruce (2016). "The sixth sense in mammalians forerunners: variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic eutheriodont therapsids". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.00219.2015.

- ^ Smith, Krister T.; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Köhler, Gunther; Habersetzer, Jörg (April 2018). "The Only Known Jawed Vertebrate with Four Eyes and the Bauplan of the Pineal Complex". Current Biology. 28 (7): 1101–1107.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.021.

- ^ Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

External links

edit- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.