Paolo Di Canio (born 9 July 1968) is an Italian former professional footballer and manager. During his playing career he made over 500 league appearances and scored over one hundred goals as a forward. He primarily played as a deep-lying forward, but he could also play as an attacking midfielder, or as a winger. Di Canio was regarded as a technically skilled but temperamental player.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

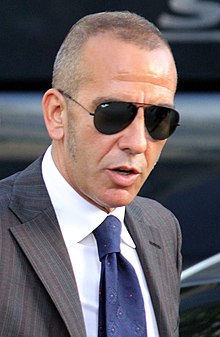

Di Canio in 2010 | |||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Paolo Di Canio[1] | ||

| Date of birth | 9 July 1968[1] | ||

| Place of birth | Rome, Italy[1] | ||

| Height | 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in)[2] | ||

| Position(s) | Forward | ||

| Youth career | |||

| Lazio | |||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) |

| 1985–1990 | Lazio | 54 | (4) |

| 1986–1987 | → Ternana (loan) | 27 | (2) |

| 1990–1993 | Juventus | 78 | (6) |

| 1993–1994 | Napoli | 26 | (5) |

| 1994–1996 | Milan | 37 | (6) |

| 1996–1997 | Celtic | 26 | (12) |

| 1997–1999 | Sheffield Wednesday | 41 | (15) |

| 1999–2003 | West Ham United | 118 | (47) |

| 2003–2004 | Charlton Athletic | 31 | (4) |

| 2004–2006 | Lazio | 50 | (11) |

| 2006–2008 | Cisco Roma | 46 | (14) |

| Total | 534 | (126) | |

| International career | |||

| 1988–1990 | Italy U21 | 9 | (2) |

| 1989 | Italy B[3] | 1 | (0) |

| Managerial career | |||

| 2011–2013 | Swindon Town | ||

| 2013 | Sunderland | ||

| *Club domestic league appearances and goals | |||

Di Canio began his career in the Italian Serie A, playing for Lazio, Juventus, Napoli and Milan, before a brief spell with the Scottish club Celtic. He subsequently spent seven years in the English Premier League with Sheffield Wednesday, West Ham United and Charlton Athletic. He returned to Italy in 2004, playing for Lazio and Cisco Roma before retiring in 2008. He played for the Italian under-21s, making nine appearances and scoring twice, and was a member of the squad that finished in third place at the 1990 UEFA European Under-21 Championship under manager Cesare Maldini, but was never capped for the senior team.[10]

Among the individual awards he received as a player, Di Canio was named SPFA Players' Player of the Year in 1997 and West Ham's player of the season in 2000. However, his career was at times characterised by controversy: he received an eleven-match ban in 1998 for pushing a referee and attracted negative publicity over his allegiance to fascism.

In 2011, Di Canio entered football management in England with Swindon Town, guiding them in his first full season as manager to promotion to League One. He was appointed as the Sunderland manager at the end of March 2013 but was sacked on 22 September after Sunderland had won only three of thirteen games under his managership.

Early life

editDi Canio was born in Rome, in the district of Quarticciolo, a working-class area populated mainly by Roma fans. However, Di Canio was drawn to their local rivals Lazio. As a young boy, he was addicted to cola and similar drinks and called Pallocca, a slang term meaning lard-ball. He was fat and knock-kneed, and needed to wear orthopedic shoes – "But I never hid. My response was to exercise; to try to become the kind of person I am."[11]

Playing career

editItaly

editHe signed for Lazio in 1985 and remained there until 1990. Lazio won promotion to Serie A in 1988, having narrowly escaped relegation to Serie C1 the year before. He finally made his first-team debut in October 1988 and went on to play 30 games during the 1988–89 season.[12] Di Canio scored the winner in the first Rome derby of the season, a goal which contributed to Lazio's survival in Serie A that season and earning him hero status. In 1990, he was sold to another of Italy's biggest clubs, Juventus;[12] although he won the UEFA Cup with the Turin side in 1993, he struggled to gain playing time during his tenure with the club, because of the presence of other forwards and creative midfielders in the team, such as Roberto Baggio, Salvatore Schillaci, Pierluigi Casiraghi, Fabrizio Ravanelli, Gianluca Vialli and Andreas Möller.[7] He left Juventus after an "animated exchange" with then manager Giovanni Trapattoni[11][13] and spent the 1993–94 season with Napoli.[11] Two seasons followed at AC Milan, where, despite winning the Serie A title in 1996, he once again struggled to gain playing time because of heavy competition from his teammates, culminating in another row, this time with Fabio Capello.[11][13][7][6]

Celtic

editIn July 1996 he joined Celtic in Scotland. In his first season at the club, he scored 15 goals in 37 appearances[14] and won the SPFA Player of the Year award.[15] However, his time in Glasgow was dogged by controversy; he was sent off during a 2–2 draw against Hearts in November 1996[16] and was heavily involved in an acrimonious league match against Rangers in March 1997 where he behaved aggressively towards Ian Ferguson and gestured in the direction of Rangers' bench as he was led from the field by teammates.[15] He was called to the referee's room after the teams had returned to the dressing room and was shown another yellow card in addition to the one he had received earlier in the game.[15] He demanded a large wage rise at the end of the season, but this was rejected by Celtic.[15] He then refused to join the squad in the Netherlands for their pre-season training during July 1997.[12]

Sheffield Wednesday

editOn 6 August 1997, Di Canio moved to the English Premiership as he joined Sheffield Wednesday in a transfer deal valued at around £4.2 million.[15] Whilst in Sheffield, Di Canio was the club's leading goal scorer for the 1997–98 season with 14 goals and he became a favourite of the fans.

In September 1998, Di Canio pushed referee Paul Alcock to the ground after being sent off while playing for Sheffield Wednesday against Arsenal at Hillsborough, which resulted in an extended ban of eleven matches.[17] and him being fined £10,000.[18]

West Ham United

editIn January 1999, Di Canio signed for West Ham United for £1.5 million. He had not played football since his ban following his push on Paul Alcock. West Ham manager Harry Redknapp, on signing Di Canio, admitted he was taking a chance but said of the player "He can do things with the ball that people can only dream of". Di Canio said of his ban, "I made a mistake and I'm sorry. West Ham have given me a big chance and I'm very happy."[19] He scored his first goal for West Ham on 27 February 1999 in his fourth game. Playing against Blackburn Rovers, Di Canio made the first goal in a 2–0 win, for Ian Pearce in the 27th minute and scored the second in the 31st minute.[20] He helped them to achieve a high league position (5th) and qualify for the UEFA Cup through the Intertoto Cup. He was also the OPTA player of the season 1998–99. He scored the BBC Goal of the Season in March 2000 with a flying volley against Wimbledon,[21] which is still considered among the best goals in Premiership history[22] and was named as the Premiership's goal of the decade in a December 2009 Sky Sports News viewers' poll, scoring 30% of votes.[23] In this season he was also voted Hammer of the Year by the club's fans.

In December 2000, late in a game against Everton and with both sides vying for the winning goal, Di Canio shunned a goal-scoring opportunity and stopped play, grabbing the ball from a cross inside the box, as the Everton goalkeeper Paul Gerrard was lying injured on the ground after he twisted his knee attempting a clearance on the edge of the box. The Goodison Park crowd reacted with a standing ovation. FIFA officially lauded Di Canio's gesture, describing it as "a special act of good sportsmanship,"[24] and awarded him next year the FIFA Fair Play Award.

Sir Alex Ferguson tried to sign him for Manchester United halfway through the 2001–02 season, but his attempts were unsuccessful and Di Canio remained in East London for another season and a half.[25] Di Canio insisted that he would not have been able to leave West Ham, who had handed him a "lifeline" in the "worst moment" in his life.[26]

In 2003, with the Hammers struggling at the bottom of the league, Di Canio had a very public row with manager Glenn Roeder and was dropped from the first team. However, he returned at the end of the season (after Roeder, stricken by a brain tumour, was replaced by Trevor Brooking) and scored a winner against Chelsea in the penultimate game of the season, a game that boosted West Ham's chances of staying in the Premiership.[27] However, they were relegated on the final day of the season after a 2–2 draw away to Birmingham City, where Di Canio scored an 89th-minute equaliser.[28] He was released on a free transfer and signed with Charlton Athletic for the start of the 2003–04 season.[29]

Charlton Athletic

editIn his one season at The Valley, Di Canio helped Charlton finish the season in 7th place, the club's highest league finish since 1953. However, he only scored four league goals for the Addicks, all of which came from the penalty spot (one from a rebound). One of the penalty kicks was an audacious "Panenka"-style penalty kick against Arsenal.[30][31] Di Canio also continued to be a provider of goals, however, notably in October 2003 when he came on as a second-half substitute with Charlton trailing 1–0 away at Portsmouth. He provided most of the spark for Charlton's much-improved second-half display, and after Jonathan Fortune had equalised for Charlton, it was from Di Canio's corner kick in the last minute that Shaun Bartlett headed home the winning goal.[32][33]

Return to Italy

editEven though he had already signed an extension to his Charlton contract, in August 2004 he returned to his home team of Lazio, taking a massive pay cut in order to return to the financially stretched Roman team.[34] Lazio fans were happy to have a Rome-bred Lazio supporter in the team again, something missing since the departure of Alessandro Nesta in 2002. He scored in the Rome derby, just as he had in 1989, leading the team to a 3–1 victory over Roma on 6 January 2005. However, the negative publicity that Di Canio generated for Lazio, including his intimate relationship with club's ultras and their increased influence due to his presence in the team, coupled with problems with some teammates and coaches, exasperated club president and majority shareholder, Claudio Lotito, with whom he already had a difficult relationship. As a result, Di Canio's contract was not renewed in the summer of 2006. During several of his games for Lazio – including during goal celebrations – Di Canio made a fascist salute to their right-wing fans.[35] He subsequently signed with Cisco Roma of Serie C2 on a free transfer. In his first season with Cisco Roma, the team finished second in the league but lost in the play-offs. He subsequently agreed to stay with Cisco for another season, in a second attempt to win promotion to Serie C1 with the Roman side.

On 10 March 2008, Di Canio announced his retirement from football, ending his 23-year playing career before the end of the season because of physical issues. It was his intention to begin coaching lessons at Coverciano to gain a coaching position.[36] In an interview he revealed that his dream would be to manage former club West Ham, and applied for the position after the resignation of Alan Curbishley in September 2008.[37] Di Canio played in Tony Carr's testimonial game at Upton Park on 5 May 2010, which featured a West Ham team against West Ham Academy old boys. He played for both sides during the match. The West Ham team won 5–1.[38] In July 2010, in honour of Di Canio, West Ham announced the opening of the Paolo Di Canio Lounge, within the West Stand, at their Upton Park ground,[39] which was formally launched by the unveiling of a plaque by Di Canio himself, on 11 September 2010.[40]

International

editDi Canio was never capped for Italy at senior level, although at U21 level he earned eleven call-ups and nine caps between 1988 and 1990, scoring twice.[41]

Style of play

editA versatile attacker, Di Canio primarily played as a deep-lying forward, but he could also play as an attacking midfielder, or as a winger. A talented yet controversial player, Di Canio was predominantly known for his creativity, eye for goal, technical ability, and dribbling skills, as well as his quick feet and intelligent play on the pitch, and was described as having "an eye for the spectacular" by The Irish Times in 2001, and as a "mercurial" player by Chris Howie of beIN Sports in 2020; however, he was equally known for being inconsistent and for his temperamental character, as well as his tenacity and aggression on the pitch.[4][5][6][7][8][9][42][43][44][45]

Managerial career

editSwindon Town

editOn 20 May 2011, Di Canio was appointed manager of Swindon Town on a two-year contract, following the club's relegation to League Two.[46] Di Canio began his career as a manager with a 3–0 win over Crewe Alexandra on 6 August 2011.[47] On 30 August 2011, Di Canio was involved in a pitch-side altercation with Swindon striker Leon Clarke after their defeat in the League Cup to Southampton.[48] In January 2012, Swindon caused a FA Cup shock by defeating Premier League club Wigan Athletic 2–1. Di Canio stated that he believed his players deserved to have their names put on the stadium and dedicated the victory to his father, who died late in 2011.[49] He was sent to the stands later in the month in a league game against Macclesfield Town for vociferously venting his frustration at his side not being awarded a free-kick. Swindon won the match 1–0 and with over half the season gone, his team were fighting for promotion to League One.[50]

Under Di Canio, Swindon reached the 2012 Football League Trophy Final, where they were defeated 2–0 by Chesterfield.[51]

On 21 April 2012, Swindon were promoted to the League One after Crawley Town's 1–1 draw with Dagenham & Redbridge and Torquay United's 2–0 loss to AFC Wimbledon, despite Di Canio's side having lost 3–1 to Gillingham on the same day. He dedicated the promotion to his parents, his mother having died shortly after his father in April of that year.[52] One week later, Swindon won the League Two title thanks to an emphatic 5–0 victory over Port Vale.[53] Swindon finished the season on 93 points.[54]

Although in the 2012–13 season, Swindon were knocked out of the FA Cup and the Football League Trophy in their first games against lower-league opposition, they did have a solid run in the League Cup in which they won against three teams from higher leagues. They beat Brighton & Hove Albion 3–0, won against Stoke City 4–3 after extra time, and beat Burnley 3–1 before narrowly missing out against Aston Villa 3–2 at home.

On 18 January 2013, ahead of Swindon's Saturday clash with Shrewsbury Town, Di Canio worked into the night alongside approximately 200 volunteers to clear a snow-covered pitch at the County Ground, thus allowing the game to go ahead. He showed his appreciation by ordering the volunteers pizza. Swindon won the match 2–0, which Di Canio publicly deemed a present to the volunteers.[55][56][57]

In January 2013, the Swindon Town chairman announced that because of financial difficulties, no money would be made available for future signings. Di Canio offered to pay £30,000 of his own money to keep loan players John Bostock, Chris Martin and Danny Hollands at the club.[58] With the possibility of the club entering administration, a new buyer was found, subject to Football League approval, and without the knowledge of Di Canio, player Matt Ritchie was sold to AFC Bournemouth. Further attempts to sign players by Di Canio were rejected by the Football League because of the club's financial situation, with Di Canio "considering his future" at Swindon because of off-field financial problems. In February, Di Canio offered his resignation but said he would withdraw this if approval for the new owners, by the Football League, was received by 18 February. This did not happen, and he resigned as manager of Swindon Town.[59]

Sunderland

editOn 31 March 2013, Sunderland appointed Di Canio as manager on a two-and-a-half-year contract, following the dismissal of Martin O'Neill the previous day.[60] The appointment prompted the immediate resignation of club vice-chairman David Miliband over Di Canio's "past political statements".[61] The appointment of Di Canio also sparked opposition from the Durham Miners' Association,[62] which decided to remove one of its mining banners from Sunderland's Stadium of Light, which is built on the former site of the Monkwearmouth Colliery, as a symbol of its anger over the appointment.[63][64] The background to the opposition was past statements made by Di Canio supporting fascism.[62][65]

Di Canio was tasked with keeping Sunderland in the Premier League, following a run of only three points from a possible 24. His first game as manager of Sunderland resulted in a 2–1 away defeat to Chelsea.[66] Di Canio's second game in charge was the Tyne–Wear derby against Newcastle United at St James' Park on 14 April. Sunderland defeated their fierce rivals 3–0, their first away victory in the fixture in over a decade. Each goal sparked wild celebrations from Di Canio and the Sunderland bench.[67] Di Canio then got his first win at the Stadium of Light against Everton.[68]

Although the team did not win the next three matches, including drawing the final two home games and a heavy 6–1 defeat to Aston Villa, Sunderland secured their Premier League survival when Wigan Athletic were defeated at Arsenal and relegated, trailing then-17th placed Sunderland by four points with only one game to play.[69]

For the 2013–14 season, Di Canio was asked to integrate thirteen players signed by Roberto De Fanti and cope with the loss of experienced players such as Simon Mignolet,[70] James McClean[71] and Stéphane Sessègnon.[72] After five league games, Sunderland had gained only a single point, from an away draw with Southampton.[73] Di Canio was dismissed on 22 September 2013, the day after the fifth match of the season, a 3–0 defeat to West Bromwich Albion, and only his 13th match in charge.[74] Sunderland chief executive officer Margaret Byrne stated that Di Canio had been sacked after senior players had approached her and that his situation became untenable because of his "brutal and vitriolic" criticism of the squad.[75] Di Canio denies this.[76]

Subsequent managerial links

editDi Canio was linked with the Celtic job in May 2014,[77] and applied for vacant managerial positions at Bolton Wanderers in October 2014,[78] and Rotherham United in September 2015[79] and again in February 2016.[80]

Political views

editIn 2005, he characterised his political views by declaring that he was "a fascist, not a racist".[81]

His use of the Roman salute toward Lazio supporters, a gesture adopted by Italian fascists in the 20th century, has created controversy. Documented uses of the salute include in matches against arch-rivals Roma and Livorno, a club inclined to left-wing politics.[82] Di Canio received a one-match ban after the second event and was fined €7,000.[83] He was later quoted as saying, "I will always salute as I did because it gives me a sense of belonging to my people ... I saluted my people with what for me is a sign of belonging to a group that holds true values, values of civility against the standardisation that this society imposes upon us."[84] His salute has been featured on unofficial merchandise sold outside Stadio Olimpico after the ban.[82]

He has also expressed admiration for the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. In his 2001 autobiography Paolo Di Canio: l'Autobiografia (Paolo Di Canio: The Autobiography), published by Libreria dello Sport,[85] he praised Mussolini as "basically a very principled, ethical individual" who was "deeply misunderstood".[86][87]

In 2010, Di Canio attended the funeral of senior fascist Paolo Signorelli, where mourners were photographed making mass fascist salutes towards Signorelli's coffin.[88] Signorelli had been convicted of involvement in the 1980 Bologna massacre, a neo-fascist terrorist attack which killed 85 people and wounded more than 200.[89]

Di Canio's political ideology has been a source of controversy in the course of his managerial career. When Di Canio was appointed as the manager of Swindon Town in 2011, the trade union GMB terminated its sponsorship agreement with the club, worth around £4,000 per season, because of Di Canio's fascist views.[90]

He was appointed as manager of Sunderland on 31 March 2013. The club's vice-chairman David Miliband, a Labour politician and former foreign secretary, subsequently stepped down. Miliband stated that he had taken the decision to resign "in the light of the new manager's past political statements".[61] It also met opposition from the Durham Miners' Association,[62] which threatened to remove one of its mining banners from Sunderland's Stadium of Light, which is built on the former site of the Wearmouth Colliery, as a symbol of its anger over the appointment.[91][92]

In a profile piece in 2011, an unnamed source asserted that Di Canio was not "an ideological fascist", attributing his behaviour to "his psychological history, particularly his former compulsive tendencies and pronounced mood swings". In the same article, Di Canio said that he was not politically active: "I don't vote, I haven't voted for 14 years. Italian politicians — all of them — think only about themselves, and making money."[86]

Personal life

editDi Canio has several tattoos, including on his right biceps the Latin word "DUX", meaning "leader" or, in Italian, Il Duce—a nickname for Benito Mussolini.[93] Sky Sports Italia was forced to apologise after Di Canio appeared as a pundit in September 2016 in a short-sleeved shirt, thus revealing the tattoo to television viewers; he was later suspended by the station.[94] His back is covered with a tattoo of fascist imagery, including an eagle, fasces, and a portrait of Mussolini.[95] He also has a West Ham United tattoo on his left upper arm[96] and a tattoo of his father on his chest.[97]

Di Canio has spoken also of the growing influence in his life of Samurai culture, and of the Japanese spiritual mentality from reading Mishima, and the teachings in the traditions of Hagakure and Bushido.[11]

Career statistics

editClub

edit| Club | Season | League | Cup1 | League Cup2 | Continental3 | Other4 | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Ternana (loan) | 1986–87 | Serie C2 | 27 | 2 | 6 | 3 | — | 33 | 5 | |||||

| Lazio | 1988–89 | Serie A | 30 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 36 | 2 | ||||||

| 1989–90 | Serie A | 24 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 4 | |||||||

| Total | 54 | 4 | 8 | 2 | — | 62 | 6 | |||||||

| Juventus | 1990–91 | Serie A | 23 | 3 | 6 | 0 | — | 5 | 0 | — | 34 | 3 | ||

| 1991–92 | Serie A | 24 | 0 | 9 | 1 | — | 33 | 1 | ||||||

| 1992–93 | Serie A | 31 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 44 | 4 | |||||

| Total | 78 | 6 | 19 | 1 | — | 14 | 0 | — | 111 | 7 | ||||

| Napoli | 1993–94 | Serie A | 26 | 5 | 1 | 0 | — | — | — | 27 | 5 | |||

| Milan | 1994–95 | Serie A | 15 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 19 | 1 | ||||

| 1995–96 | Serie A | 22 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 34 | 6 | |||||

| Total | 37 | 6 | 6 | 1 | — | 10 | 0 | — | 53 | 7 | ||||

| Celtic[98] | 1996–97 | Scottish Premier Division | 26 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | — | 37 | 15 | |

| Sheffield Wednesday | 1997–98 | Premier League | 35 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | — | 40 | 14 | |||

| 1998–99 | Premier League | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | |||||

| Total | 41 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | — | 48 | 17 | |||||

| West Ham United | 1998–99 | Premier League | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 13 | 4 | ||

| 1999–2000 | Premier League | 30 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 45 | 18 | |||

| 2000–01 | Premier League | 31 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | — | 37 | 11 | ||||

| 2001–02 | Premier League | 26 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 9 | |||||

| 2002–03 | Premier League | 18 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 9 | |||||

| Total | 118 | 47 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 1 | — | 141 | 51 | |||

| Charlton Athletic | 2003–04 | Premier League | 31 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | — | 33 | 5 | |||

| Lazio | 2004–05 | Serie A | 23 | 6 | 1 | 0 | — | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 7 | |

| 2005–06 | Serie A | 27 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | — | 32 | 7 | ||||

| Total | 50 | 11 | 2 | 0 | — | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 62 | 14 | |||

| Cisco Roma | 2006–07 | Serie C2 | 28 | 7 | 5 | 3 | — | 33 | 10 | |||||

| 2007–08 | Serie C2 | 18 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 7 | |||||||

| Total | 46 | 14 | 7 | 3 | — | 53 | 17 | |||||||

| Career total | 534 | 126 | 64 | 14 | 15 | 5 | 46 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 670 | 149 | ||

- 1.^ Includes Coppa Italia, Scottish Cup and FA Cup

- 2.^ Includes Scottish League Cup and EFL Cup.

- 3.^ Includes UEFA Champions League and UEFA Cup.

- 4.^ Includes Supercoppa Italiana.

Managerial statistics

edit- As of 22 September 2013

| Team | From | To | Record | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | W | D | L | Win % | ||||

| Swindon Town | 20 May 2011 | 18 February 2013 | 95 | 54 | 18 | 23 | 56.8 | [99] |

| Sunderland | 31 March 2013 | 22 September 2013 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 23.1 | [74][99] |

| Total | 108 | 57 | 21 | 30 | 52.8 | — | ||

Honours

editPlayer

editLazio[6]

- Serie B promotion: 1987–88

- Supercoppa Italiana runner-up: 2004

Juventus[5]

- UEFA Cup: 1992–93

- Coppa Italia runner-up: 1991–92

Milan[6]

- Serie A: 1995–96

- UEFA Super Cup: 1994

- Intercontinental Cup runner-up: 1994

West Ham United

Individual

- PFA Scotland Players' Player of the Year: 1996–97[101]

- Sheffield Wednesday F.C. Player of the Year: 1998[102]

- Hammer of the Year: 2000[103]

- BBC Goal of the Season: 1999–2000[104]

- FIFA Fair Play Award: 2001[24]

Manager

editSwindon Town

Individual

References

edit- ^ a b c "Paolo Di Canio". Barry Hugman's Footballers. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Di Canio: Paolo Di Canio". Premier League. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Courtney, Barrie (22 May 2014). "England – International Results B-Team – Details". RSSSF. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Di Canio, Paolo". tuttocalciatori.net (in Italian). Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b c "Paolo Di Canio" (in Italian). Il Pallone Racconta. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Paolo di Canio". magliarossonera.it (in Italian). Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d Stefano Bedeschi (10 July 2014). "Gli eroi in bianconero: Paolo DI CANIO" (in Italian). Tutto Juve. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b Thorpe, Lee (14 June 2011). "English Premier League: Ranking 60 of the Best Overseas Players in EPL History". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b Taylor, Daniel (4 January 2002). "Maverick worth the risk". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Nazionale in Cifre: Convocazioni e presenze in campo – Di Canio, Paolo". figc.it (in Italian). FIGC. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Paolo Di Canio: 'My life speaks for me' – Profiles – People". The Independent. London. 11 December 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "Paolo Di Canio factfile". Sky Sports. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ a b Fisher, Stewart (20 February 2013). "Is Di Canio a martyr or does he have a hidden agenda?". Herald Scotland. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ Haggerty, Anthony (24 December 2008). "Subbuteo team was reason I joined Celtic, admits Paolo Di Canio". Daily Record. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Di Canio's Celtic years: good, bad and ugly". The Scotsman. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "Paolo's Italian for loco". Scotland on Sunday. 1 December 1996. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Di Canio gets 11-match ban for push on ref". BBC Sport. 23 October 1998.

- ^ "Di Canio ban too short, say referees". BBC Sport. 24 October 1998.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (28 January 1999). "West Ham sign £1.5m Di Canio". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Callow, Nick (27 February 1999). "Di Canio strikes right note". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "West Ham 2 Wimbledon 1". Sporting Life. UK. Retrieved 1 May 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Raynor, Dominic (23 October 2009). "Paolo Di Canio: Explosive Italian". ESPN FC. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Football Tonight". Sky Sports News. 31 December 2009. 50 (approx) minutes in. BSkyB.

- ^ a b "Di Canio wins Fair Play award". BBC News. 17 December 2001. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Ferguson: 21 that got away – Manchester Evening News". Menmedia.co.uk. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Di Canio reveals Ferguson reaction after he rejected Man Utd". 8 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Di Canio grabs West Ham lifeline". BBC News. 3 May 2003. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Birmingham 2 West Ham 2". Sporting Life. UK. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Di Canio joins Charlton". BBC Sport. 11 August 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Arsenal back on top". BBC Sport. 26 October 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Wright, Matt. "Extra time with Paolo Di Canio". Voice of the Valley. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Charlton snatch late win". BBC News. 4 October 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Stone, Jimmy (21 November 2013). "CAFC Moments: Di Canio inspires comeback". cafc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Lazio offer has di Canio begging Charlton for release". TheGuardian.com. 5 August 2004.

- ^ "I'm a fascist, not a racist, says Paolo di Canio". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "Di Canio Smette di giocare, addio alla Cisco Roma". Yahoo! Eurosport Italia. 10 March 2008.

- ^ "Di Canio wants to be Hammers boss". BBC Sport. 4 September 2008.

- ^ "Paolo's pride". Whufc.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Take your seat in the Di Canio Lounge | West Ham United". Whufc.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Di Canio Lounge a hit". West Ham United F.C. Archived from the original on 16 September 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Convocazioni e presenze in campo: DI CANIO PAOLO" (in Italian). FIGC. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Kanoute always happy to go against the tide". The Irish Times. 27 January 2001. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Howie, Chris (9 April 2020). "One of a Kind – Frederic Kanoute". beIN SPORTS. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Edwards, John (2 July 2001). "£6m Di Canio fee floors Ferguson". ESPN.com. Retrieved 17 August 2020. [dead link]

- ^ Frostick, Nancy (23 April 2020). "'For Benny and Paolo it didn't matter what day it was, they were gung-ho.'". The Athletic. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "Swindon Town confirm Paolo Di Canio as new manager". BBC Sport. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Swindon 3-0 Crewe". BBC Sport. 5 August 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Time called on Clarke". Swindon Advertiser. 1 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Swindon 2 – 1 Wigan". BBC Sport. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ "Swindon 1 – 0 Macclesfield". BBC Sport. 21 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ Wembley, Sachin Nakrani at (25 March 2012). "Chesterfield 2-0 Swindon Town | Johnstone's Paint Trophy match report". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ Crook, Alex (21 April 2012). "Gillingham 3 Swindon Town 1: match report". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Swindon 5–0 Port Vale". BBC. 28 April 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Football League 2 table 2011/12". footballsite. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio shovels snow off Swindon pitch and orders pizza for helpers". Metro. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "PDC – Victory a present". Swindon Town FC. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Shrewsbury game on". Swindon Town FC. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio offers own money to keep Swindon players". BBC Sport. 7 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio quits as manager of Swindon Town". BBC Sport. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio appointed Sunderland head coach". BBC Sport. 31 March 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b Quinn, Ben (1 April 2013). "David Miliband quits Sunderland FC in Di Canio protest". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "Miners' Di Canio protest 'will only end with Sunderland campaign support'". BBC News. 6 April 2013.

- ^ "Durham Miners' Association: Our Issues With Di Canio At Sunderland Now Resolved – Sky Tyne and Wear". Archived from the original on 25 June 2013.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (2 April 2013). "Sunderland miners demand return of banner after Paolo Di Canio's arrival". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Miners join opposition to Paolo Di Canio's appointment at Sunderland". The Independent. London. 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Premier League round-up – Sky Sports". Sky Sports.

- ^ "Newcastle 0 Sunderland 3". BBC Sport. 14 April 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Luke (20 April 2013). "Sunderland 1 Everton 0". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Podolski double condemns Wigan to relegation". Global Post. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Luke (25 June 2013). "Liverpool sign Sunderland goalkeeper Simon Mignolet". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Wigan: James McClean took pay cut to join – Owen Coyle". BBC Sport. 9 August 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Luke (20 September 2013). "Sunderland manager Paolo Di Canio: I had to sell Stephane Sessegnon to West Bromwich Albion". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Southampton 1-1 Sunderland". BBC Sport. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ a b Rose, Gary (22 September 2013). "Paolo Di Canio: Sunderland reign that lasted only six months". BBC Sport. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio: Sunderland players met CEO before sacking". BBC Sport. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio denies bust-up with players caused Sunderland exit". BBC Sport. BBC. 1 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio puts himself forward for Celtic manager's job". The Guardian. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Hunter, Andy (8 October 2014). "Paolo Di Canio and Neil Lennon apply for job as Bolton Wanderers manager". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Rotherham reject approach from Paolo Di Canio over manager's job". The Guardian. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio applies for Rotherham manager job for second time". The Guardian. 8 February 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Fenton, Ben (24 December 2005). "I'm a fascist, not a racist, says Paolo di Canio". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ a b Kassimeris, Christos (2008). European football in black and white: tackling racism in football. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 70. ISBN 9780739119600.

- ^ Bar-On, Tamir (2007). Where have all the fascists gone?. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 1. ISBN 9780754671541.

- ^ Nursey, James (19 December 2005). "Football: ll Di Canio new salute row". Daily Mirror. London (UK). Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ "PAOLO DI CANIO – L'AUTOBIOGRAFIA" (in Italian). libreriadellosport.it. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Paolo Di Canio: 'My life speaks for me'". The Independent. London. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Duff, Mark (9 January 2005). "Footballer's 'fascist salute' row". BBC News. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ "HOPE not hate news: Paolo Di Canio at bomb fascist's funeral". Archived from the original on 6 April 2013.

- ^ Sergio Zavoli, La notte della Repubblica, Nuova Eri, 1992 (in Italian).

- ^ "Swindon sponsor pulls out after Paolo Di Canio appointment". The Guardian. 21 May 2011.

- ^ Daunt, Joe. "Durham Miners' Association: Our Issues With Di Canio at Sunderland Now Resolved". Sky Tyne and Wear. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (2 April 2013). "Sunderland miners demand return of banner after Paolo Di Canio's arrival". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Political Football: Paolo Di Canio". Channel 4. 26 April 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Dobson, Mark (14 September 2016). "Sky Sport Italia suspends Paolo Di Canio after showing 'dux' tattoo". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Mussolini tattoos and fascist salutes: The troubling political history of former Sheffield Wednesday forward Paolo Di Canio". www.thestar.co.uk.

- ^ "Where Are They Now? Paolo Di Canio". 27 March 2018.

- ^ Warren, Andy (1 May 2012). "The man with the Swindon tattoo (From Swindon Advertiser)". Swindonadvertiser.co.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Player Details – Di Canio, Paolo". FitbaStats – Celtic. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Managers: Paolo Di Canio". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Intertoto win gives Hammers Uefa spot". BBC. 24 August 1999. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/sheffield-wednesday-legend-paolo-di-canio-announces-return-city-158272 [dead link]

- ^ "Sheffield Wed Player of the Year 1969-2021".

- ^ "Awards". West Ham United F.C. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Swindon Town confirm Paolo di Canio as new manager". BBC Sport. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ "Chesterfield 2–0 Swindon". BBC Sport. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b "NPower Manager of the Month". Football League. September 2011 – April 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

Bibliography

edit- Paolo Di Canio, Paolo Di Canio: l'Autobiografia, Milan, Libreria dello Sport, 2001, ISBN 88-86753-40-3 (Paolo Di Canio: The Autobiography). (in Italian)

External links

edit- Paolo Di Canio at TuttoCalciatori.net (in Italian)

- Profile at FIGC (in Italian)

- Paolo Di Canio at Premier League