Pensions in the United States consist of the Social Security system, public employees retirement systems, as well as various private pension plans offered by employers, insurance companies, and unions.

History

editWhile various iterations of what could be considered pensions existed before the declared independence of the United States, most were designed solely for veterans of wars or set up as charitable initiatives by Church communities. This trend continued throughout early American history, with much of the first veterans' pension under the newly formed United States offered to retired naval officers in 1799.[2]

The United States Congress later created the Bureau of Pensions to oversee an increasing number of veterans' pensions in 1832 following the granting of pensions to all American Revolutionary War veterans. Eventually, responsibility for these pensions would be transferred to the Department of the Interior in 1849 as returning veterans from the Mexican–American War put further stress on the system.[3]

At the outset of the Civil War the General Law pension system was established by congress for both volunteer and conscripted soldiers fighting in the Union Army.[4] Payouts derived from this plan were based on degree of injury and subject to review by government boards. By 1890, general old-age pensions were incorporated for Union veterans.[5]

Outside of veterans' pensions, the institution of the first public pension plan for New York City Police is considered as the first iteration of a modern pension in the USA. The Police Life and Health Insurance Fund, created in 1857, provided payment to officers injured or otherwise disabled in the line of duty and offered compensation in a lump sum to families of officers killed in action.[6] The fund was initially funded not by state or municipal budgets, but by the sales of unclaimed stolen property, rewards, voluntary contributions and fines collected for violations of Sunday laws,[7] proving sufficient for the relatively low enrollment and demands of the initial plan.

The compensation scheme later came to cover firefighters as well, growing into a lifetime pension plan about 20 years after its initial creation, with added funding from more substantial sources.[8]

Within the private sector, the American Express and Baltimore and Ohio Railroad defined benefit pension plans are considered the first instances of major employers instituting a fully fledged retirement plan[9] The plans came to be established in 1875 and 1880 respectively.[10]

The United States saw significant growth in pension plans, both public and private, throughout the Progressive Era as labor sought more rights from larger, and often more industrialized employers. Private employer retirement plans also grew substantially following the passage of the Revenue Act of 1913, which implicitly granted tax exempt status to retirement plans, making them more economically desirable.[11]

Subsequent revenue acts in 1921 and 1926 added further, explicit benefits to contributions made to employees retirement plans (both defined contribution and benefit) spurring further growth.[12]

The establishment of the Social Security system and numerous New Deal initiatives aimed at providing a safe net for elderly Americans caused an explosion in the size of the nation's federal retirement investment.

From the New Deal through the 1960s, numerous federal acts and regulations were created in order to encourage and protect the growing number of pensioners in the US. In particular, early retirement options were added to Social Security benefits and IRS regulations were created that clearly defined tax policies and benefits to pensioners.[13] By the late 1960s, almost half of all employed persons in the United States had some form of pension.[14]

However, the next seminal event in the history of pensions would be the creation of the Employees Retirement Income Security Act, ostensibly enacted in response to the failure of Studebaker and the loss of pension benefits promised to thousands of employees.[15] Among other things, the act set fiduciary duties over pension plans, set funding requirements, and created the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation as a backstop to defined benefit plans.

Further shifts in tax regulations, age of participation, vesting status, and contribution limits would be set throughout the Reagan, Clinton, and Bush administrations. Most notably, the Retirement Equity Act of 1984 and The Tax Reform Act of 1986 made significant changes to maternity leave implications for retirement savings' vesting schedules, specific compensation brackets, and attempted to unify rules for individual retirement accounts.[16] Both acts built upon changes made in the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982.

Despite reform legislation under discussion in the ensuing decades, pension participation particularly in the private sector continues to decline. From a peak of nearly 50% prior to the ERISA, now less than 10% of private sector employees are granted a defined benefit pension plan[17]

Types

editA Defined Benefit Plan is commonly recognized as a "pension" in the United States. The structure of these plans guarantees a payout to a retiree following their date of retirement. This contrasts with a Defined Contribution Plan which creates a trust based on the amount invested by an employee during their working years. IRA, 401k plans, 403b, and 457 plans are prominent examples of the latter [19][better source needed] and are not generally considered pensions in common parlance.

Qualified vs. non-qualified plans

editPensions can either be qualified or non-qualified under U.S. law. For defined benefit plans, the benefits of a qualified plan are protections under the Employees Retirement Income Security Act and offer tax incentives for contributions made by employers to fund the plans.[20]

Non-Qualified plans are generally offered to employees at the higher echelons of companies as they do not qualify for income restrictions related to pensions.[21][better source needed] Typical iterations of these plans include executive bonus structures and life insurance contracts. Plans are also typically deferred compensation rather than defined benefit.[22]

Public, private, and union distinctions

editThere are also delineations drawn between public pensions, private company pensions, and multi-employer pensions governed under Taft-Hartley Act regulations.

Multi-employer plans

editMulti-employer pensions necessitate a collective bargaining agreement between multiple employers and a labor union. The benefit of this structure is the mobility of labor between these employers without amending retirement and health benefits. A primary example of the benefit of these plans are the nations' Teamsters Unions whose employment demands necessitate movement across many geographies, maintaining benefits in each region.[23]

Multi-employer plans have courted a large degree of criticism in recent decades for corruption related to mob involvement and general misappropriation of pension funds.[24]

In response to growing concerns over funded ratios, the U.S. Congress enacting the Multi-employer Pension Protection Act of 1980 to increase funding requirements and curb bankruptcy fears.[25] Nonetheless, Congress was compelled to establish further regulations and restrictions on the specific stripe of plan in 2014 with the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014 (MPRA).[26] Given the billions of dollars in unfunded pension liabilities, the bill proposed reductions of pension benefits to plans slated to become insolvent.[27] The act also enforced penalty premiums on plans that necessitate PBGC intervention.

Social Security in the United States

editSocial Security, officially known as the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, is a federal initiative administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA). It provides retirement benefits, survivor benefits, and disability income to eligible individuals and their families, serving as a crucial safety net for millions of Americans.

Social Security operates as an insurance program, where workers contribute to the system through payroll withholding. Self-employed individuals pay Social Security taxes when filing their federal tax returns. Workers can earn up to four credits each year, based on their annual earnings. These credits determine eligibility for benefits, with workers needing at least 40 credits (equivalent to 10 years of work) to qualify for retirement benefits.

The contributions made by workers flow into two trust funds: the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund (OASI) and the Disability Insurance Trust Fund (DI). These funds are overseen by a board of trustees, including government officials and public representatives. The board ensures the proper management and utilization of funds to meet the program's obligations to beneficiaries.

Medicare, a federal health insurance program primarily for individuals aged 65 and older, is also supported through payroll withholding. Contributions for Medicare go into a separate trust fund managed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Workers become eligible for retirement benefits at age 62, but the amount of benefits increases for those who delay claiming until their full retirement age (FRA), which ranges from 66 to 67 depending on birth year. Benefits continue to increase for those who delay beyond their FRA until age 70. The amount of benefits is calculated based on the worker's average indexed monthly earnings (AIME) during their 35 highest-earning years.

Social Security also provides disability benefits for individuals unable to work due to physical or mental impairments. These benefits offer crucial support to disabled individuals and their families, ensuring financial stability during times of hardship. Survivor benefits are available to the spouse, children, and other dependents of deceased workers, providing essential income assistance to families dealing with the loss of a breadwinner.¨

Social Security remains a critical pillar of retirement security for millions of Americans. While it provides valuable support, it is essential to supplement Social Security benefits with other retirement savings and investment vehicles to ensure financial stability in retirement. As policymakers work to address the program's challenges, maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of Social Security is vital to safeguarding the well-being of current and future beneficiaries.[28]

Tax law

editVarious federal tax provisions of the Internal Revenue Code apply to pension plans. Similar rules apply to profit-sharing plans and stock bonus plans, which are commonly used for retirement savings. Significant portions of these tax law provisions parallel portions of ERISA (see discussion in a preceding section of this article).

Contributions made to qualified pension plans can be deducted from taxable income, subject to specific limits. Any dividends and capital gains within these accounts are not taxed until they are withdrawn, allowing for tax-deferred growth. Upon withdrawal, the entire amount is taxed as regular income.

Employees have the option to designate part or all of their contributions to a 401(k) plan as Roth contributions. These Roth contributions are made with after-tax dollars and do not provide immediate tax benefits, as they are included in gross income. However, unlike traditional 401(k) plans, the investment returns and benefits in Roth accounts remain tax-free. Additionally, unlike traditional plans, Roth 401(k) plans do not mandate withdrawals at a certain age. Retirees have the flexibility to choose when and if they withdraw their accumulated assets.

Bankruptcy law

editIn April 2012, the Northern Mariana Islands Retirement Fund filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The retirement fund is a defined benefit type pension plan and was only partially funded by the government, with only $268.4 million in assets and $911 million in liabilities. The plan experienced low investment returns and a benefit structure that had been increased without raises in funding.[29]

According to "Pensions and Investments", this is "apparently the first" US public pension plan to declare bankruptcy.[29]

See also

editReferences

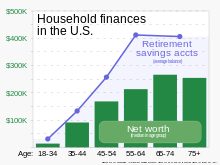

edit- ^ Dagher, Veronica; Tergesen, Anne; Ettenheim, Rosie (March 31, 2023). "Here's What Retirement Looks Like in America in Six Charts". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023.

(For Average household retirement savings account balance:) Estimates of 401(k), IRA, Keogh and other defined contribution account balances based on 2019 data. Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute. . . . (For median net worth:) Source: Federal Reserve.

- ^ Clark, R. L., Craig, L. A., & Wilson, J. W. (1999). The Life and Times of a Public-Sector Pension Plan before Social Security: The US Navy Pension Plan in the Nineteenth Century. Life, 1, 1-1999.

- ^ Davies, W. E. (1948). The Mexican War veterans as an organized group. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 35(2), 221-238.

- ^ Costa, D. L. (1995). Pensions and retirement: Evidence from union army veterans. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 297-319.

- ^ ibid

- ^ "PPF History - New York City Police Pension Fund".

- ^ ibid

- ^ ibid

- ^ Seburn, P. W. (1991). Evolution of employer-provided defined benefit pensions. Monthly Labor Review, 114(12), 16-23.

- ^ ibid

- ^ Flexibility, W. (2010). A Timeline of the Evolution of Retirement in the United States.

- ^ ibid

- ^ ibid

- ^ ibid

- ^ "History of PBGC | Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation".

- ^ Flexibility, W. (2010). A Timeline of the Evolution of Retirement in the United States. Georgetown Press.

- ^ Wiatrowski, William J. (December 2012). "The last private industry pension plans: a visual essay" (PDF). Monthly Labor Review. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ "Actuarial Life Table". U.S. Social Security Administration Office of Chief Actuary. 2020. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023.

- ^ "457 Plan".

- ^ Internal Revenue Service. "A Guide to Common Qualified Plan Requirements." Accessed April 26, 2020

- ^ "Reading into Nonqualified Plans".

- ^ ibid

- ^ "Introduction to Multiemployer Plans | Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation".

- ^ Marte, J. (2016). One of the nation’s largest pension funds could soon cut benefits for retirees. The Washington Post.

- ^ "Introduction to Multiemployer Plans | Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation".

- ^ ibid

- ^ ibid

- ^ https://www.ssa.gov/ [bare URL]

- ^ a b Mercado, Darla (2012-04-19). "In apparent first, a public pension plan files for bankruptcy". Pensions and Investments. Retrieved 2012-04-28.