Peripheral neuropathy, often shortened to neuropathy, refers to damage or disease affecting the nerves.[1] Damage to nerves may impair sensation, movement, gland function, and/or organ function depending on which nerve fibers are affected. Neuropathies affecting motor, sensory, or autonomic nerve fibers result in different symptoms. More than one type of fiber may be affected simultaneously. Peripheral neuropathy may be acute (with sudden onset, rapid progress) or chronic (symptoms begin subtly and progress slowly), and may be reversible or permanent.

| Peripheral neuropathy | |

|---|---|

| |

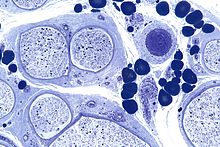

| Micrograph showing a vasculitic peripheral neuropathy; plastic embedded; Toluidine blue stain | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Shooting pain, numbness, tingling, tremors, bladder problems, unsteadiness |

Common causes include systemic diseases (such as diabetes or leprosy), hyperglycemia-induced glycation,[2][3][4] vitamin deficiency, medication (e.g., chemotherapy, or commonly prescribed antibiotics including metronidazole and the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics (such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin)), traumatic injury, ischemia, radiation therapy, excessive alcohol consumption, immune system disease, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, or viral infection. It can also be genetic (present from birth) or idiopathic (no known cause).[5][6][7][8] In conventional medical usage, the word neuropathy (neuro-, "nervous system" and -pathy, "disease of")[9] without modifier usually means peripheral neuropathy.

Neuropathy affecting just one nerve is called "mononeuropathy", and neuropathy involving nerves in roughly the same areas on both sides of the body is called "symmetrical polyneuropathy" or simply "polyneuropathy". When two or more (typically just a few, but sometimes many) separate nerves in disparate areas of the body are affected it is called "mononeuritis multiplex", "multifocal mononeuropathy", or "multiple mononeuropathy".[5][6][7]

Neuropathy may cause painful cramps, fasciculations (fine muscle twitching), muscle loss, bone degeneration, and changes in the skin, hair, and nails. Additionally, motor neuropathy may cause impaired balance and coordination or, most commonly, muscle weakness; sensory neuropathy may cause numbness to touch and vibration, reduced position sense causing poorer coordination and balance, reduced sensitivity to temperature change and pain, spontaneous tingling or burning pain, or allodynia (pain from normally nonpainful stimuli, such as light touch); and autonomic neuropathy may produce diverse symptoms, depending on the affected glands and organs, but common symptoms are poor bladder control, abnormal blood pressure or heart rate, and reduced ability to sweat normally.[5][6][7]

Classification

editPeripheral neuropathy may be classified according to the number and distribution of nerves affected (mononeuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, or polyneuropathy), the type of nerve fiber predominantly affected (motor, sensory, autonomic), or the process affecting the nerves; e.g., inflammation (neuritis), compression (compression neuropathy), chemotherapy (chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy). The affected nerves are found in an EMG (electromyography) / NCS (nerve conduction study) test and the classification is applied upon completion of the exam.[10]

Mononeuropathy

editMononeuropathy is a type of neuropathy that only affects a single nerve.[11] Diagnostically, it is important to distinguish it from polyneuropathy because when a single nerve is affected, it is more likely to be due to localized trauma or infection.[citation needed]

The most common cause of mononeuropathy is physical compression of the nerve, known as compression neuropathy. Carpal tunnel syndrome and axillary nerve palsy are examples. Direct injury to a nerve, interruption of its blood supply resulting in (ischemia), or inflammation also may cause mononeuropathy.[citation needed]

Polyneuropathy

edit"Polyneuropathy" is a pattern of nerve damage that is quite different from mononeuropathy, often more serious and affecting more areas of the body. The term "peripheral neuropathy" sometimes is used loosely to refer to polyneuropathy. In cases of polyneuropathy, many nerve cells in various parts of the body are affected, without regard to the nerve through which they pass; not all nerve cells are affected in any particular case. In distal axonopathy, one common pattern is that the cell bodies of neurons remain intact, but the axons are affected in proportion to their length; the longest axons are the most affected. Diabetic neuropathy is the most common cause of this pattern. In demyelinating polyneuropathies, the myelin sheath around axons is damaged, which affects the ability of the axons to conduct electrical impulses. The third and least common pattern affects the cell bodies of neurons directly. This affects the sensory neurons (known as sensory neuronopathy or dorsal root ganglionopathy).[12][13]

The effect of this is to cause symptoms in more than one part of the body, often symmetrically on the left and right sides. As for any neuropathy, the chief symptoms include motor symptoms such as weakness or clumsiness of movement; and sensory symptoms such as unusual or unpleasant sensations such as tingling or burning; reduced ability to feel sensations such as texture or temperature, and impaired balance when standing or walking. In many polyneuropathies, these symptoms occur first and most severely in the feet. Autonomic symptoms also may occur, such as dizziness on standing up, erectile dysfunction, and difficulty controlling urination.[citation needed]

Polyneuropathies usually are caused by processes that affect the body as a whole. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance are the most common causes. Hyperglycemia-induced formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) is related to diabetic neuropathy.[14] Other causes relate to the particular type of polyneuropathy, and there are many different causes of each type, including inflammatory diseases such as Lyme disease, vitamin deficiencies, blood disorders, and toxins (including alcohol and certain prescribed drugs).

Most types of polyneuropathy progress fairly slowly, over months or years, but rapidly progressive polyneuropathy also occurs. It is important to recognize that at one time it was thought that many of the cases of small fiber peripheral neuropathy with typical symptoms of tingling, pain, and loss of sensation in the feet and hands were due to glucose intolerance before a diagnosis of diabetes or pre-diabetes. However, in August 2015, the Mayo Clinic published a scientific study in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences showing "no significant increase in...symptoms...in the prediabetes group", and stated that "A search for alternate neuropathy causes is needed in patients with prediabetes."[15]

The treatment of polyneuropathies is aimed firstly at eliminating or controlling the cause, secondly at maintaining muscle strength and physical function, and thirdly at controlling symptoms such as neuropathic pain.[citation needed]

Mononeuritis multiplex

editMononeuritis multiplex, occasionally termed polyneuritis multiplex, is simultaneous or sequential involvement of individual noncontiguous nerve trunks,[16] either partially or completely, evolving over days to years and typically presenting with acute or subacute loss of sensory and motor function of individual nerves. The pattern of involvement is asymmetric. However, as the disease progresses, deficit(s) becomes more confluent and symmetrical, making it difficult to differentiate from polyneuropathy.[17] Therefore, attention to the pattern of early symptoms is important.

Mononeuritis multiplex is sometimes associated with a deep, aching pain that is worse at night and frequently in the lower back, hip, or leg. In people with diabetes mellitus, mononeuritis multiplex typically is encountered as acute, unilateral, and severe thigh pain followed by anterior muscle weakness and loss of knee reflex.[medical citation needed]

Electrodiagnostic medicine studies will show multifocal sensory motor axonal neuropathy.[citation needed]

It is caused by, or associated with, several medical conditions:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Vasculitides: polyarteritis nodosa,[18][19] granulomatosis with polyangiitis[19] and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[19] This results in vasculitic neuropathy.

- Immune-mediated diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis,[20] systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Infections: leprosy, lyme disease, parvovirus B19,[21] HIV[22]

- Sarcoidosis[23]

- Cryoglobulinemia[24]

- Reactions to exposure to chemical agents, including trichloroethylene and dapsone[medical citation needed]

- Rarely, following the sting of certain jellyfish, such as the sea nettle[medical citation needed]

Autonomic neuropathy

editAutonomic neuropathy is a form of polyneuropathy that affects the non-voluntary, non-sensory nervous system (i.e., the autonomic nervous system), affecting mostly the internal organs such as the bladder muscles, the cardiovascular system, the digestive tract, and the genital organs. These nerves are not under a person's conscious control and function automatically. Autonomic nerve fibers form large collections in the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis outside the spinal cord. They have connections with the spinal cord and ultimately the brain, however. Most commonly autonomic neuropathy is seen in persons with long-standing diabetes mellitus type 1 and 2. In most—but not all—cases, autonomic neuropathy occurs alongside other forms of neuropathy, such as sensory neuropathy.[citation needed]

Autonomic neuropathy is one cause of malfunction of the autonomic nervous system, but not the only one; some conditions affecting the brain or spinal cord also may cause autonomic dysfunction, such as multiple system atrophy, and therefore, may cause similar symptoms to autonomic neuropathy.[citation needed]

The signs and symptoms of autonomic neuropathy include the following:

- Urinary bladder conditions: bladder incontinence or urine retention

- Gastrointestinal tract: dysphagia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, malabsorption, fecal incontinence, gastroparesis, diarrhoea, constipation

- Cardiovascular system: disturbances of heart rate (tachycardia, bradycardia), orthostatic hypotension, inadequate increase of heart rate on exertion

- Respiratory system: impairments in the signals associated with regulation of breathing and gas exchange (central sleep apnea, hypopnea, bradypnea).[25]

- Skin: thermal regulation, dryness through sweat disturbances

- Other areas: hypoglycemia unawareness, genital impotence

Neuritis

editNeuritis is a general term for inflammation of a nerve[26] or the general inflammation of the peripheral nervous system. Symptoms depend on the nerves involved, but may include pain, paresthesia (pins-and-needles), paresis (weakness), hypoesthesia (numbness), anesthesia, paralysis, wasting, and disappearance of the reflexes.

Causes of neuritis include:

- Physical injury

- Infection

- Diphtheria

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Leprosy

- Lyme disease

- Chemical injury such as chemotherapy

- Radiation therapy

Types of neuritis include:

- Brachial neuritis

- Cranial neuritis such as Bell's palsy

- Optic neuritis

- Vestibular neuritis

- Wartenberg's migratory sensory neuropathy

- Underlying conditions including:

- Alcoholism

- Autoimmune disease, especially multiple sclerosis and Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Beriberi (vitamin B1 deficiency)

- Cancer

- Celiac disease[27]

- Non-celiac gluten sensitivity[8]

- Diabetes mellitus (Diabetic neuropathy)

- Hypothyroidism

- Porphyria

- Vitamin B12 deficiency[28]

- Vitamin B6 excess[29]

Signs and symptoms

editThose with diseases or dysfunctions of their nerves may present with problems in any of the normal nerve functions. Symptoms vary depending on the types of nerve fiber involved.[30] [citation needed] In terms of sensory function, symptoms commonly include loss of function ("negative") symptoms, including numbness, tremor, impairment of balance, and gait abnormality.[31] Gain of function (positive) symptoms include tingling, pain, itching, crawling, and pins-and-needles. Motor symptoms include loss of function ("negative") symptoms of weakness, tiredness, muscle atrophy, and gait abnormalities; and gain of function ("positive") symptoms of cramps, and muscle twitch (fasciculations).[32]

In the most common form, length-dependent peripheral neuropathy, pain and parasthesia appear symmetrically and generally at the terminals of the longest nerves, which are in the lower legs and feet. Sensory symptoms generally develop before motor symptoms such as weakness. Length-dependent peripheral neuropathy symptoms make a slow ascent of the lower limbs, while symptoms may never appear in the upper limbs; if they do, it will be around the time that leg symptoms reach the knee.[33] When the nerves of the autonomic nervous system are affected, symptoms may include constipation, dry mouth, difficulty urinating, and dizziness when standing.[32]

CAP-PRI scale for diagnosis

editA user-friendly, disease-specific, quality-of-life scale can be used to monitor how someone is doing living with the burden of chronic, sensorimotor polyneuropathy. This scale, called the Chronic, Acquired Polyneuropathy - Patient-reported Index (CAP-PRI), contains only 15 items and is completed by the person affected by polyneuropathy. The total score and individual item scores can be followed over time, with item scoring used by the patient and care provider to estimate the clinical status of some of the more common life domains and symptoms impacted by polyneuropathy.[34]

Causes

editThe causes are grouped broadly as follows:

- Ribose-5-Phosphate Isomerase Deficiency

- Surgery: LASIK (corneal neuropathy — 20 to 55% of people).[35]

- Genetic diseases: Friedreich's ataxia, Fabry disease,[36] Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease,[37] hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy

- Hyperglycemia-induced formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs)[14][38][39]

- Metabolic and endocrine diseases: diabetes mellitus,[36] chronic kidney failure, porphyria, amyloidosis, liver failure, hypothyroidism[40]

- Idiopathic peripheral neuropathy refers to neuropathy with no known cause.[41]

- Toxic causes: drugs (vincristine, metronidazole, phenytoin, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid, ethyl alcohol, statins),[medical citation needed] organic herbicides TCDD dioxin, organic metals, heavy metals, excess intake of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine). Peripheral neuropathies also may result from long-term (more than 21 days) treatment with linezolid.[medical citation needed]

- Adverse effects of fluoroquinolones: irreversible neuropathy is a serious adverse reaction of fluoroquinolone drugs[42]

- Inflammatory diseases: Guillain–Barré syndrome,[36] systemic lupus erythematosus, leprosy, Sjögren's syndrome, Babesiosis, Lyme disease,[36] vasculitis,[36] sarcoidosis.[43] Multiple sclerosis may also be causal.[36][44]

- Vitamin deficiency states: Vitamin B12 (Methylcobalamin),[36] vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin B1 (thiamin)

- Physical trauma: compression, automobile accident, sports injury, sports pinching, cutting, projectile injuries (for example, gunshot wound), strokes including prolonged occlusion of blood flow, electric discharge, including lightning strikes[medical citation needed]

- Effect of chemotherapy – see Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy[36]

- Exposure to Agent Orange[45]

- Others: Carpal tunnel syndrome, electric shock, HIV,[36][46] malignant disease, radiation, shingles, MGUS (Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance).[47]

Diagnosis

editPeripheral neuropathy may first be considered when an individual reports symptoms of numbness, tingling, and pain in feet. After ruling out a lesion in the central nervous system as a cause, a diagnosis may be made on the basis of symptoms, laboratory and additional testing, clinical history, and a detailed examination.

During physical examination, specifically a neurological examination, those with generalized peripheral neuropathies most commonly have distal sensory or motor and sensory loss, although those with a pathology (problem) of the nerves may be perfectly normal; may show proximal weakness, as in some inflammatory neuropathies, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome; or may show focal sensory disturbance or weakness, such as in mononeuropathies. Classically, ankle jerk reflex is absent in peripheral neuropathy.

A physical examination will involve testing the deep ankle reflex as well as examining the feet for any ulceration. For large fiber neuropathy, an exam will usually show an abnormally decreased sensation to vibration, which is tested with a 128-Hz tuning fork, and decreased sensation of light touch when touched by a nylon monofilament.[33]

Diagnostic tests include electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCSs), which assess large myelinated nerve fibers.[33] Testing for small-fiber peripheral neuropathies often relates to the autonomic nervous system function of small thinly- and unmyelinated fibers. These tests include a sweat test and a tilt table test. Diagnosis of small fiber involvement in peripheral neuropathy may also involve a skin biopsy in which a 3 mm-thick section of skin is removed from the calf by a punch biopsy, and is used to measure the skin intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), the density of nerves in the outer layer of the skin.[31] Reduced density of the small nerves in the epidermis supports a diagnosis of small-fiber peripheral neuropathy.

In EMG testing, demyelinating neuropathy characteristically shows a reduction in conduction velocity and prolongation of distal and F-wave latencies, whereas axonal neuropathy shows a reduction in amplitude.[48]

Laboratory tests include blood tests for vitamin B12 levels, a complete blood count, measurement of thyroid stimulating hormone levels, a comprehensive metabolic panel screening for diabetes and pre-diabetes, and a serum immunofixation test, which tests for antibodies in the blood.[32]

Treatment

editThe treatment of peripheral neuropathy varies based on the cause of the condition, and treating the underlying condition can aid in the management of neuropathy. When peripheral neuropathy results from diabetes mellitus or prediabetes, blood sugar management is key to treatment. In prediabetes in particular, strict blood sugar control can significantly alter the course of neuropathy.[31] In peripheral neuropathy that stems from immune-mediated diseases, the underlying condition is treated with intravenous immunoglobulin or steroids. When peripheral neuropathy results from vitamin deficiencies or other disorders, those are treated as well.[31]

Medications

editA range of medications that act on the central nervous system have been used to symptomatically treat neuropathic pain. Commonly used medications include tricyclic antidepressants (such as nortriptyline,[49] amitriptyline.[50] imapramine,[51] and desipramine,[52]) serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) medications (duloxetine,[53] venlafaxine,[54] and milnacipran[55]) and antiepileptic medications (gabapentin,[56] pregabalin,[57] oxcarbazepine[58] zonisamide[59] levetiracetam,[60] lamotrigine,[61] topiramate,[62] clonazepam,[63] phenytoin,[64] lacosamide,[65] sodium valproate[66] and carbamazepine[67]). Opioid and opiate medications (such as buprenorphine,[68] morphine,[69] methadone,[70] fentanyl,[71] hydromorphone,[72] tramadol[73] and oxycodone[74]) are also often used to treat neuropathic pain.

As is revealed in many of the Cochrane systematic reviews listed below, studies of these medications for the treatment of neuropathic pain are often methodologically flawed and the evidence is potentially subject to major bias. In general, the evidence does not support the usage of antiepileptic and antidepressant medications for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Better-designed clinical trials and further review from non-biased third parties are necessary to gauge just how useful for patients these medications truly are. Reviews of these systematic reviews are also necessary to assess their failings.

It is also often the case that the aforementioned medications are prescribed for neuropathic pain conditions for which they had not been explicitly tested on or for which controlled research is severely lacking; or even for which evidence suggests that these medications are not effective.[75][76][77] The NHS for example explicitly states that amitriptyline and gabapentin can be used for treating the pain of sciatica.[78] This is despite both the lack of high-quality evidence that demonstrates the efficacy of these medications for that symptom,[50][56] and also the prominence of generally moderate to high-quality evidence that reveals that antiepileptics in specific, including gabapentin, demonstrate no efficacy in treating it.[79]

Antidepressants

editIn general, according to Cochrane's systematic reviews, antidepressants have shown to either be ineffective for the treatment of neuropathic pain or the evidence available is inconclusive.[49][52][80][81] Evidence also tends to be tainted by bias or issues with the methodology.[82][83]

Cochrane systematically reviewed the evidence for the antidepressants nortriptyline, desipramine, venlafaxine, and milnacipran and in all these cases found scant evidence to support their use for the treatment of neuropathic pain. All reviews were done between 2014 and 2015.[49][52][80][81]

A 2015 Cochrane systematic review of amitriptyline found that there was no evidence supporting the use of amitriptyline that did not possess inherent bias. The authors believe amitriptyline may have an effect in some patients but that the effect is overestimated.[82] A 2014 Cochrane systematic review of imipramine notes that the evidence suggesting benefit were "methodologically flawed and potentially subject to major bias."[83]

A 2017 Cochrane systematic review assessed the benefit of antidepressant medications for several types of chronic non-cancer pains (including neuropathic pain) in children and adolescents and the authors found the evidence inconclusive.[84]

Antiepileptics

editA 2017 Cochrane systematic review found that daily dosages between 1800–3600 mg of gabapentin could provide good pain relief for pain associated with diabetic neuropathy only. This relief occurred for roughly 30–40% of treated patients, while placebo had a 10–20% response. Three of the seven authors of the review had conflicts of interest declared.[56] In a 2019 Cochrane review of pregabalin the authors conclude that there is some evidence of efficacy in the treatment of pain deriving from post-herpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-traumatic neuropathic pain only. They also warned that many patients treated will have no benefit. Two of the five authors declared receiving payments from pharmaceutical companies.[57]

A 2017 Cochrane systematic review found that oxcarbazepine had little evidence to support its use for treating diabetic neuropathy, radicular pain, and other neuropathies. The authors also call for better studies.[58] In a 2015 Cochrane systematic review the authors found a lack of evidence showing any effectiveness of zonisamide for the treatment of pain deriving from any peripheral neuropathy.[59] A 2014 Cochrane review found that studies of levetiracetam showed no indication of its effectiveness at treating pain from any neuropathy. The authors also found that the evidence was possibly biased and that some patients experienced adverse events.[85]

A 2013 Cochrane systematic review concluded that there was high-quality evidence to suggest that lamotrigine is not effective for treating neuropathic pain, even at high dosages 200–400 mg.[86] A 2013 Cochrane systematic review of topirimate found that the included data had a strong likelihood of major bias; despite this, it found no effectiveness for the drug in treating the pain associated with diabetic neuropathy. It had not been tested for any other type of neuropathy.[62] Cochrane reviews from 2012 of clonazepam and phenytoin uncovered no evidence of sufficient quality to support their use in chronic neuropathic pain."[87][88]

A 2012 Cochrane systematic review of lacosamide found it very likely that the drug is ineffective for treating neuropathic pain. The authors caution against positive interpretations of the evidence.[89] For sodium valproate the authors of a 2011 Cochrane review found that "three studies no more than hint that sodium valproate may reduce pain in diabetic neuropathy". They discuss how there is a probable overestimate of the effect due to the inherent problems with the data and conclude that the evidence does not support its usage.[90] In a 2014 systematic review of carbamazepine the authors believe the drug to be of benefit to some people. No trials were considered greater than level III evidence; none were longer than 4 weeks in length or were deemed as having good reporting quality.[91]

A 2017 Cochrane systematic review aiming to assess the benefit of antiepileptic medications for several types of chronic non-cancer pains (including neuropathic pain) in children and adolescents found the evidence inconclusive. Two of the ten authors of this study declared receiving payments from pharmaceutical companies.[92]

Opioids

editA Cochrane review of buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, and morphine, all dated between 2015 and 2017, and all for the treatment of neuropathic pain, found that there was insufficient evidence to comment on their efficacy. Conflicts of interest were declared by the authors in this review.[68][69][71][72] A 2017 Cochrane review of methadone found very low-quality evidence, three studies of limited quality, of its efficacy and safety. They could not formulate any conclusions about its relative efficacy and safety compared to a placebo.[70]

For tramadol, Cochrane found that there was only modest information about the benefits of its usage for neuropathic pain. Studies were small, had potential risks of bias and apparent benefits increased with risk of bias. Overall the evidence was of low or very low quality and the authors state that it "does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect".[73] For oxycodone the authors found very low-quality evidence showing its usefulness in treating diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia only. One of the four authors declared receiving payments from pharmaceutical companies.[74]

More generally, a large-scale 2013 review found opioids to be more effective for intermediate-term use than short-term use, but couldn't properly assess effectiveness for chronic use because of insufficient data. Most recent guidelines on the pharmacotherapy of neuropathic pain however are in agreement with the results of this review and recommend the use of opioids.[93] A 2017 Cochrane review examining mainly propoxyphene therapy as a treatment for many non-cancer pain syndromes (including neuropathic pain) concluded, "There was no evidence from randomised controlled trials to support or refute the use of opioids to treat chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents."[94]

Others

editA 2016 Cochrane review of paracetamol for the treatment of neuropathic pain concluded that its benefit alone or in combination with codeine or dihydrocodeine is unknown.[95]

Few studies have examined whether nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective in treating peripheral neuropathy.[96]

There is some evidence that symptomatic relief from the pain of peripheral neuropathy may be obtained by the application of topical capsaicin. Capsaicin is the factor that causes heat in chili peppers. However, the evidence suggesting that capsaicin applied to the skin reduces pain for peripheral neuropathy is of moderate to low quality and should be interpreted carefully before this treatment is used.[97]

Evidence supports the use of cannabinoids for some forms of neuropathic pain.[98] A 2018 Cochrane review of cannabis-based medicines for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain included 16 studies. All of these studies included THC as a pharmacological component of the test group. The authors rated the quality of evidence as very low to moderate. The primary outcome was quoted as, "Cannabis-based medicines may increase the number of people achieving 50% or greater pain relief compared with placebo" but "the evidence for improvement in Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) with cannabis to be of very low quality". The authors also conclude, "The potential benefits of cannabis-based medicine... might be outweighed by their potential harms."[99]

A 2014 Cochrane review of topical lidocaine for the treatment of various peripheral neuropathies found its usage supported by a few low-quality studies. The authors state that no high-quality randomised control trials demonstrate its efficacy or safety profile.[100]

A 2015 (updated in 2022) Cochrane review of topical clonidine for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy included two studies of 8 and 12 weeks in length; both of which compared topical clonidine to placebo and both of which were funded by the same drug manufacturer. The review found that topical clonidine may provide some benefit versus placebo. However, the authors state that the included trials are potentially subject to significant bias and that the evidence is of low to moderate quality.[101]

A 2007 Cochrane review of aldose reductase inhibitors for the treatment of pain deriving from diabetic polyneuropathy found it no better than a placebo.[102]

Medical devices

editTranscutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) therapy is often used to treat various types of neuropathy. A 2010 review of three trials, for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy explicitly, involving a total of 78 patients found some improvement in pain scores after 4 and 6 but not 12 weeks of treatment and an overall improvement in neuropathic symptoms at 12 weeks.[103] Another 2010 review of four trials, for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy, found significant improvement in pain and overall symptoms, with 38% of patients in one trial becoming asymptomatic. The treatment remains effective even after prolonged use, but symptoms return to baseline within a month of cessation of treatment.[104]

These older reviews can be balanced with a more recent 2017 review of TENS for neuropathic pain by Cochrane which concluded that "This review is unable to state the effect of TENS versus sham TENS for pain relief due to the very low quality of the included evidence... The very low quality of evidence means we have very limited confidence in the effect estimate reported." A very low quality of evidence means, 'multiple sources of potential bias' with a 'small number and size of studies'.[105]

Surgery

editPeripheral neuropathy due to nerve compression is treatable with a nerve decompression.[106][107][108][109] When a nerve is subject to localized pressure or stretching, the vascular supply is interrupted leading to a cascade of physiological changes that causes nerve injury.[110] In a nerve decompression, a surgeon explores the entrapment site and removes tissue around the nerve to relieve pressure. Common sites of entrapment are spaces of anatomic narrowing such as osteofibrous tunnels (e.g. carpal tunnel in carpal tunnel syndrome).[111] In many cases the potential for nerve recovery (full or partial) after decompression is excellent, as chronic nerve compression is associated with low-grade nerve injury (Sunderland classification I-III) rather than high-grade nerve injury (Sunderland classification IV-V).[112] Nerve decompressions for properly selected patients are associated with a significant reduction in pain, in some cases the complete elimination of pain.[113][106][107]

In people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, two reviews make a case for nerve decompression surgery as an effective means of pain relief and support claims for protection from foot ulceration.[114][115] There is less evidence for efficacy of surgery for non-diabetic peripheral neuropathy of the legs and feet. One uncontrolled study that performed before/after comparisons with a minimum of one-year follow-up reported improvements in pain relief, impaired balance, and numbness. "There was no difference in outcomes between patients with diabetic versus idiopathic neuropathy in response to nerve decompression."[41] There are no placebo-controlled trials for idiopathic peripheral neuropathy in the published scientific literature.

Diet

editAccording to a review, strict gluten-free diet is an effective treatment when neuropathy is caused by gluten sensitivity, with or without the presence of digestive symptoms or intestinal injury.[8]

Counselling

editA 2015 review on the treatment of neuropathic pain with psychological therapy concluded that "There is insufficient evidence of the efficacy and safety of psychological interventions for chronic neuropathic pain. The two available studies show no benefit of treatment over either waiting list or placebo control groups."[116]

Alternative medicine

editA 2019 Cochrane review of the treatment of herbal medicinal products for people with neuropathic pain for at least three months concluded that "There was insufficient evidence to determine whether nutmeg or St John's wort has any meaningful efficacy in neuropathic pain conditions. The quality of the current evidence raises serious uncertainties about the estimates of effect observed, therefore, we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect."[117]

A 2017 Cochrane review on the usage of acupuncture as a treatment for neuropathic pain concludes, "Due to the limited data available, there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of acupuncture for neuropathic pain in general, or for any specific neuropathic pain condition when compared with sham acupuncture or other active therapies." Also, "Most studies included a small sample size (fewer than 50 participants per treatment arm) and all studies were at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel." Also, the authors state, "we did not identify any study comparing acupuncture with treatment as usual."[118]

Alpha lipoic acid (ALA) with benfotiamine is a proposed pathogenic treatment for painful diabetic neuropathy only.[119] The results of two systematic reviews state that oral ALA produced no clinically significant benefit, intravenous ALA administered over three weeks may improve symptoms and that long-term treatment has not been investigated.[120]

Research

editA 2008 literature review concluded that "based on principles of evidence-based medicine and evaluations of methodology, there is only a 'possible' association of celiac disease and peripheral neuropathy due to lower levels of evidence and conflicting evidence. There is not yet convincing evidence of causality."[121]

A 2019 review concluded that "gluten neuropathy is a slowly progressive condition. About 25% of the patients will have evidence of enteropathy on biopsy (CD [celiac disease]) but the presence or absence of an enteropathy does not influence the positive effect of a strict gluten-free diet."[8]

Stem-cell therapy is also being looked at as a possible means to repair peripheral nerve damage but efficacy has not yet been demonstrated.[122][123][124]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Kaur J, Ghosh S, Sahani AK, Sinha JK (November 2020). "Mental Imagery as a Rehabilitative Therapy for Neuropathic Pain in People With Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 34 (11): 1038–1049. doi:10.1177/1545968320962498. PMID 33040678. S2CID 222300017.

- ^ Sugimoto K, Yasujima M, Yagihashi S (2008). "Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 14 (10): 953–61. doi:10.2174/138161208784139774. PMID 18473845.

- ^ Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS (February 2014). "Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications". The Korean Journal of Physiology & Pharmacology. 18 (1): 1–14. doi:10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.1. PMC 3951818. PMID 24634591.

- ^ Jack M, Wright D (May 2012). "Role of advanced glycation endproducts and glyoxalase I in diabetic peripheral sensory neuropathy". Translational Research. 159 (5): 355–65. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2011.12.004. PMC 3329218. PMID 22500508.

- ^ a b c Hughes RA (February 2002). "Peripheral neuropathy". BMJ. 324 (7335): 466–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7335.466. PMC 1122393. PMID 11859051.

- ^ a b c Torpy JM, Kincaid JL, Glass RM (April 2010). "JAMA patient page. Peripheral neuropathy". JAMA. 303 (15): 1556. doi:10.1001/jama.303.15.1556. PMID 20407067.

- ^ a b c "Peripheral neuropathy fact sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 19 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Zis P, Hadjivassiliou M (February 2019). "Treatment of Neurological Manifestations of Gluten Sensitivity and Coeliac Disease". Current Treatment Options in Neurology (Review). 21 (3): 10. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0552-7. PMID 30806821. S2CID 73466457.

- ^ "neuropathy". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Volume 12, Spring 1999 | University of Pennsylvania Orthopaedic Journal". Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:mononeuropathy".

- ^ Amato AA, Ropper AH (22 October 2020). "Sensory Ganglionopathy". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (17): 1657–1662. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2023935. PMID 33085862.

- ^ Gwathmey KG (January 2016). "Sensory neuronopathies". Muscle & Nerve. 53 (1): 8–19. doi:10.1002/mus.24943. PMID 26467754.

- ^ a b Sugimoto K, Yasujima M, Yagihashi S (2008). "Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 14 (10): 953–61. doi:10.2174/138161208784139774. PMID 18473845.

- ^ Kassardjian CD, Dyck PJ, Davies JL, Carter RE, Dyck PJ (August 2015). "Does prediabetes cause small fiber sensory polyneuropathy? Does it matter?". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 355 (1–2): 196–8. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.026. PMC 4621009. PMID 26049659.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Multiple mononeuropathy

- ^ Ball DA. "Peripheral Neuropathy". NeuraVite. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Criado PR, Marques GF, Morita TC, de Carvalho JF (June 2016). "Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory profiles of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa patients: Report of 22 cases and literature review". Autoimmunity Reviews. 15 (6): 558–63. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.02.010. PMID 26876385.

- ^ a b c Samson M, Puéchal X, Devilliers H, Ribi C, Cohen P, Bienvenu B, Terrier B, Pagnoux C, Mouthon L, Guillevin L (September 2014). "Mononeuritis multiplex predicts the need for immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs for EGPA, PAN and MPA patients without poor-prognosis factors". Autoimmunity Reviews. 13 (9): 945–53. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.08.002. PMID 25153486.

- ^ Hellmann DB, Laing TJ, Petri M, Whiting-O'Keefe Q, Parry GJ (May 1988). "Mononeuritis multiplex: the yield of evaluations for occult rheumatic diseases". Medicine. 67 (3): 145–53. doi:10.1097/00005792-198805000-00001. PMID 2835572. S2CID 24059700.

- ^ Lenglet T, Haroche J, Schnuriger A, Maisonobe T, Viala K, Michel Y, Chelbi F, Grabli D, Seror P, Garbarg-Chenon A, Amoura Z, Bouche P (July 2011). "Mononeuropathy multiplex associated with acute parvovirus B19 infection: characteristics, treatment and outcome". Journal of Neurology. 258 (7): 1321–6. doi:10.1007/s00415-011-5931-2. PMID 21287183. S2CID 8145505.

- ^ Kaku M, Simpson DM (November 2014). "HIV neuropathy". Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 9 (6): 521–6. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000103. PMID 25275705. S2CID 3023845.

- ^ Vargas DL, Stern BJ (August 2010). "Neurosarcoidosis: diagnosis and management". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 31 (4): 419–27. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1262210. PMID 20665392. S2CID 260321346.

- ^ Cacoub P, Comarmond C, Domont F, Savey L, Saadoun D (September 2015). "Cryoglobulinemia Vasculitis" (PDF). The American Journal of Medicine. 128 (9): 950–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.02.017. PMID 25837517. S2CID 12560858.

- ^ Vinik AI, Erbas T (2013). "Diabetic autonomic neuropathy". Autonomic Nervous System. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 117. pp. 279–94. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53491-0.00022-5. ISBN 978-0-444-53491-0. PMID 24095132.

- ^ "neuritis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Chin RL, Latov N (January 2005). "Peripheral Neuropathy and Celiac Disease". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 7 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1007/s11940-005-0005-3. PMID 15610706. S2CID 40765123.

- ^ Ghosh S, Sinha JK, Khandelwal N, Chakravarty S, Kumar A, Raghunath M (1 September 2020). "Increased stress and altered expression of histone modifying enzymes in brain are associated with aberrant behaviour in vitamin B12 deficient female mice". Nutritional Neuroscience. 23 (9): 714–723. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2018.1548676. PMID 30474509. S2CID 53785219.

- ^ Vitamin Toxicity at eMedicine

- ^ "Peripheral Neuropathy Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cioroiu CM, Brannagan TH (2014). "Peripheral Neuropathy". Current Geriatrics Reports. 3 (2): 83–90. doi:10.1007/s13670-014-0079-4. S2CID 195246984.

- ^ a b c Azhary H, Farooq MU, Bhanushali M, Majid A, Kassab MY (April 2010). "Peripheral neuropathy: differential diagnosis and management". American Family Physician. 81 (7): 887–92. PMID 20353146.

- ^ a b c Watson JC, Dyck PJ (July 2015). "Peripheral Neuropathy: A Practical Approach to Diagnosis and Symptom Management". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (7): 940–51. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004. PMID 26141332.

- ^ Gwathmey KG, Conaway MR, Sadjadi R, et al. (2015-12-29). "Construction and validation of the chronic acquired polyneuropathy patient-reported index (CAP-PRI): A disease-specific, health-related quality-of-life instrument". Muscle & Nerve. 54 (1). Muscle Nerve: 9–17. doi:10.1002/mus.24985. PMC 4950873. PMID 26600438.

- ^ Levitt AE, Galor A, Weiss JS, Felix ER, Martin ER, Patin DJ, Sarantopoulos KD, Levitt RC (April 2015). "Chronic dry eye symptoms after LASIK: parallels and lessons to be learned from other persistent post-operative pain disorders". Molecular Pain. 11: s12990–015–0020. doi:10.1186/s12990-015-0020-7. PMC 4411662. PMID 25896684.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gilron I, Baron R, Jensen T (April 2015). "Neuropathic pain: principles of diagnosis and treatment". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (4): 532–45. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.01.018. PMID 25841257.

- ^ Gabriel JM, Erne B, Pareyson D, Sghirlanzoni A, Taroni F, Steck AJ (December 1997). "Gene dosage effects in hereditary peripheral neuropathy. Expression of peripheral myelin protein 22 in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies nerve biopsies". Neurology. 49 (6): 1635–40. doi:10.1212/WNL.49.6.1635. PMID 9409359. S2CID 37715021.

- ^ Hayreh SS, Servais GE, Virdi PS (January 1986). "Fundus lesions in malignant hypertension. V. Hypertensive optic neuropathy". Ophthalmology. 93 (1): 74–87. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33773-4. PMID 3951818./

- ^ Kawana T, Yamamoto H, Izumi H (December 1987). "A case of aspergillosis of the maxillary sinus". The Journal of Nihon University School of Dentistry. 29 (4): 298–302. doi:10.2334/josnusd1959.29.298. PMID 3329218.

- ^ Wood-allum CA, Shaw PJ (2014). "Thyroid disease and the nervous system". Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part II. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 120. Elsevier. pp. 703–735. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-4087-0.00048-6. ISBN 978-0-7020-4087-0. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 24365348.

- ^ a b Valdivia JM, Weinand M, Maloney CT, Blount AL, Dellon AL (June 2013). "Surgical treatment of superimposed, lower extremity, peripheral nerve entrapments with diabetic and idiopathic neuropathy". Ann Plast Surg. 70 (6): 675–79. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182764fb0. PMID 23673565. S2CID 10150616.

- ^ Cohen JS (Dec 2001). "Peripheral neuropathy associated with fluoroquinolones". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 35 (12): 1540–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1Z429. PMID 11793615. S2CID 12589772.

- ^ Heck AW, Phillips LH (August 1989). "Sarcoidosis and the nervous system". Neurologic Clinics. 7 (3): 641–54. doi:10.1016/S0733-8619(18)30805-3. PMID 2671639.

- ^ Note NO mention of MS

- ^ "Service-Connected Disability Compensation For Exposure To Agent Orange" (PDF). Vietnam Veterans of America. April 2015. p. 4. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ Gonzalez-Duarte A, Cikurel K, Simpson DM (August 2007). "Managing HIV peripheral neuropathy". Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 4 (3): 114–8. doi:10.1007/s11904-007-0017-6. PMID 17883996. S2CID 34689986.

- ^ Nobile-Orazio E, Barbieri S, Baldini L, Marmiroli P, Carpo M, Premoselli S, Manfredini E, Scarlato G (June 1992). "Peripheral neuropathy in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: prevalence and immunopathogenetic studies". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 85 (6): 383–90. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb06033.x. PMID 1379409. S2CID 30788715.

- ^ Chung T, Prasad K, Lloyd TE (February 2014). "Peripheral Neuropathy – Clinical and Electrophysiological Considerations". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 24 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.nic.2013.03.023. PMC 4329247. PMID 24210312.

- ^ a b c Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Aldington D, Moore RA (January 2015). "Nortriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (5): CD011209. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011209.pub2. PMC 6485407. PMID 25569864.

- ^ a b Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ (July 2015). "Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (7): CD008242. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008242.pub3. PMC 6447238. PMID 26146793.

- ^ Hearn L, Derry S, Phillips T, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ (May 2014). "Imipramine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (5): CD010769. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010769.pub2. PMC 6485593. PMID 24838845.

- ^ a b c Hearn L, Moore RA, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Phillips T (September 2014). Hearn L (ed.). "Desipramine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9): CD011003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011003.pub2. PMC 6804291. PMID 25246131.

- ^ Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ (January 2014). "Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (1): CD007115. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007115.pub3. PMC 10711341. PMID 24385423.

- ^ Gallagher HC, Gallagher RM, Butler M, Buggy DJ, Henman MC (August 2015). "Venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (8): CD011091. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011091.pub2. PMC 6481532. PMID 26298465.

- ^ Derry S, Phillips T, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ (July 2015). "Milnacipran for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (7): CD011789. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011789. PMC 6485877. PMID 26148202.

- ^ a b c Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Bell RF, Rice AS, Tölle TR, Phillips T, Moore RA (June 2017). "Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (2): CD007938. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub4. PMC 6452908. PMID 28597471.

- ^ a b Derry S, Bell RF, Straube S, Wiffen PJ, Aldington D, Moore RA (January 2019). "Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD007076. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007076.pub3. PMC 6353204. PMID 30673120.

- ^ a b Zhou M, Chen N, He L, Yang M, Zhu C, Wu F (December 2017). "Oxcarbazepine for neuropathic pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (12): CD007963. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007963.pub3. PMC 6486101. PMID 29199767.

- ^ a b Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Lunn MP (January 2015). "Zonisamide for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD011241. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011241.pub2. PMC 6485502. PMID 25879104.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Lunn MP (July 2014). Derry S (ed.). "Levetiracetam for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (7): CD010943. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010943.pub2. PMC 6485608. PMID 25000215.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA (December 2013). Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group (ed.). "Lamotrigine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (12): CD006044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006044.pub4. PMC 6485508. PMID 24297457.

- ^ a b Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Lunn MP, Moore RA (August 2013). Derry S (ed.). "Topiramate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (8): CD008314. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008314.pub3. PMC 8406931. PMID 23996081.

- ^ Corrigan R, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (May 2012). "Clonazepam for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD009486. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009486.pub2. PMC 6485609. PMID 22592742.

- ^ Birse F, Derry S, Moore RA (May 2012). "Phenytoin for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD009485. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009485.pub2. PMC 6481697. PMID 22592741.

- ^ Hearn L, Derry S, Moore RA (February 2012). "Lacosamide for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (2): CD009318. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009318.pub2. PMC 8406928. PMID 22336864.

- ^ Gill D, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (October 2011). "Valproic acid and sodium valproate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (10): CD009183. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009183.pub2. PMC 6540387. PMID 21975791.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Kalso EA (April 2014). Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group (ed.). "Carbamazepine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD005451. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005451.pub3. PMC 6491112. PMID 24719027.

- ^ a b Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Stannard C, Aldington D, Cole P, Knaggs R (September 2015). "Buprenorphine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (9): CD011603. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011603.pub2. PMC 6481375. PMID 26421677.

- ^ a b Cooper TE, Chen J, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Carr DB, Aldington D, Cole P, Moore RA (May 2017). "Morphine for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD011669. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011669.pub2. PMC 6481499. PMID 28530786.

- ^ a b McNicol ED, Ferguson MC, Schumann R (May 2017). Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group (ed.). "Methadone for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD012499. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012499.pub2. PMC 6353163. PMID 28514508.

- ^ a b Derry S, Stannard C, Cole P, Wiffen PJ, Knaggs R, Aldington D, Moore RA (October 2016). "Fentanyl for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (5): CD011605. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011605.pub2. PMC 6457928. PMID 27727431.

- ^ a b Stannard C, Gaskell H, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Cooper TE, Knaggs R, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (May 2016). "Hydromorphone for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD011604. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011604.pub2. PMC 6491092. PMID 27216018.

- ^ a b Duehmke RM, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Bell RF, Aldington D, Moore RA (June 2017). "Tramadol for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (6): CD003726. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003726.pub4. PMC 6481580. PMID 28616956.

- ^ a b Gaskell H, Derry S, Stannard C, Moore RA (July 2016). Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group (ed.). "Oxycodone for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (7): CD010692. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010692.pub3. PMC 6457997. PMID 27465317.

- ^ Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE (September 2013). "Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain". JAMA Internal Medicine. 173 (17): 1573–81. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8992. PMC 4381435. PMID 23896698.

- ^ Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Hancock M, Oliveira VC, McLachlan AJ, Koes B (February 2012). "Drugs for relief of pain in patients with sciatica: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 344: e497. doi:10.1136/bmj.e497. PMC 3278391. PMID 22331277.

- ^ Pinto RZ, Verwoerd AJ, Koes BW (October 2017). "Which pain medications are effective for sciatica (radicular leg pain)?". BMJ. 359: j4248. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4248. PMID 29025735. S2CID 11229746.

- ^ "Which painkiller?". nhs.uk. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ Enke O, New HA, New CH, Mathieson S, McLachlan AJ, Latimer J, Maher CG, Lin CC (July 2018). "Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CMAJ. 190 (26): E786–E793. doi:10.1503/cmaj.171333. PMC 6028270. PMID 29970367.

- ^ a b Gallagher HC, Gallagher RM, Butler M, Buggy DJ, Henman MC (August 2015). "Venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (8): CD011091. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011091.pub2. PMC 6481532. PMID 26298465.

- ^ a b Derry S, Phillips T, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ (July 2015). "Milnacipran for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (7): CD011789. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011789. PMC 6485877. PMID 26148202.

- ^ a b Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ (July 2015). Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group (ed.). "Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (7): CD008242. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008242.pub3. PMC 6447238. PMID 26146793.

- ^ a b Hearn L, Derry S, Phillips T, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ (May 2014). "Imipramine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD010769. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010769.pub2. PMC 6485593. PMID 24838845.

- ^ Cooper TE, Heathcote LC, Clinch J, Gold JI, Howard R, Lord SM, Schechter N, Wood C, Wiffen PJ (August 2017). "Antidepressants for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD012535. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012535.pub2. PMC 6424378. PMID 28779487.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Lunn MP (July 2014). Derry S (ed.). "Levetiracetam for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (7): CD010943. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010943.pub2. PMC 6485608. PMID 25000215.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA (December 2013). "Lamotrigine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (12): CD006044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006044.pub4. PMC 6485508. PMID 24297457.

- ^ Corrigan R, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (May 2012). "Clonazepam for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD009486. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009486.pub2. PMC 6485609. PMID 22592742.

- ^ Birse F, Derry S, Moore RA (May 2012). "Phenytoin for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD009485. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009485.pub2. PMC 6481697. PMID 22592741.

- ^ Hearn L, Derry S, Moore RA (February 2012). "Lacosamide for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (2): CD009318. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009318.pub2. PMC 8406928. PMID 22336864.

- ^ Gill D, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (October 2011). "Valproic acid and sodium valproate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (10): CD009183. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009183.pub2. PMC 6540387. PMID 21975791.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Kalso EA (April 2014). "Carbamazepine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD005451. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005451.pub3. PMC 6491112. PMID 24719027.

- ^ Cooper TE, Wiffen PJ, Heathcote LC, Clinch J, Howard R, Krane E, Lord SM, Sethna N, Schechter N, Wood C (August 2017). "Antiepileptic drugs for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD012536. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012536.pub2. PMC 6424379. PMID 28779491.

- ^ McNicol ED, Midbari A, Eisenberg E (August 2013). "Opioids for neuropathic pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (8): CD006146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2. PMC 6353125. PMID 23986501.

- ^ Cooper TE, Fisher E, Gray AL, Krane E, Sethna N, van Tilburg MA, Zernikow B, Wiffen PJ (July 2017). "Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD012538. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012538.pub2. PMC 6477875. PMID 28745394.

- ^ Wiffen PJ, Knaggs R, Derry S, Cole P, Phillips T, Moore RA (December 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without codeine or dihydrocodeine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (5): CD012227. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012227.pub2. PMC 6463878. PMID 28027389.

- ^ Moore RA, Chi CC, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Rice AS (October 2015). "Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for neuropathic pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD010902. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010902.pub2. PMC 6481590. PMID 26436601.

- ^ Derry S, Rice AS, Cole P, Tan T, Moore RA (January 2017). "Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (7): CD007393. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007393.pub4. PMC 6464756. PMID 28085183.

- ^ Hill KP (June 2015). "Medical Marijuana for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Other Medical and Psychiatric Problems: A Clinical Review". JAMA. 313 (24): 2474–83. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6199. PMID 26103031.

Use of marijuana for chronic pain, neuropathic pain, and spasticity due to multiple sclerosis is supported by high-quality evidence

- ^ Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, Petzke F, Häuser W (March 2018). "Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (7): CD012182. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2. PMC 6494210. PMID 29513392.

- ^ Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, Quinlan J (July 2014). Derry S (ed.). "Topical lidocaine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (7): CD010958. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010958.pub2. PMC 6540846. PMID 25058164.

- ^ Serednicki WT, Wrzosek A, Woron J, Garlicki J, Dobrogowski J, Jakowicka-Wordliczek J, Wordliczek J, Zajaczkowska R (2022-05-19). "Topical clonidine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (5): CD010967. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010967.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 9119025. PMID 35587172.

- ^ Chalk C, Benstead TJ, Moore F (October 2007). "Aldose reductase inhibitors for the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (4): CD004572. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004572.pub2. PMC 8406996. PMID 17943821.

- ^ Jin DM, Xu Y, Geng DF, Yan TB (July 2010). "Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 89 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.021. PMID 20510476.

- ^ Pieber K, Herceg M, Paternostro-Sluga T (April 2010). "Electrotherapy for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a review". Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 42 (4): 289–95. doi:10.2340/16501977-0554. PMID 20461329.

- ^ Gibson W, Wand BM, O'Connell NE (September 2017). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (3): CD011976. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011976.pub2. PMC 6426434. PMID 28905362.

- ^ a b Kay J, de Sa D, Morrison L, Fejtek E, Simunovic N, Martin HD, Ayeni OR (December 2017). "Surgical Management of Deep Gluteal Syndrome Causing Sciatic Nerve Entrapment: A Systematic Review". Arthroscopy. 33 (12): 2263–2278.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2017.06.041. PMID 28866346.

- ^ a b ElHawary H, Barone N, Baradaran A, Janis JE (February 2022). "Efficacy and Safety of Migraine Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Outcomes and Complication Rates". Ann Surg. 275 (2): e315–e323. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005057. PMID 35007230.

- ^ Giulioni C, Pirola GM, Maggi M, Pitoni L, Fuligni D, Beltrami M, Palantrani V, De Stefano V, Maurizi V, Castellani D, Galosi AB (March 2024). "Pudendal Nerve Neurolysis in Patients Afflicted With Pudendal Nerve Entrapment: A Systematic Review of Surgical Techniques and Their Efficacy". Int Neurourol J. 28 (1): 11–21. doi:10.5213/inj.2448010.005. PMC 10990758. PMID 38569616.

- ^ Lu VM, Burks SS, Heath RN, Wolde T, Spinner RJ, Levi AD (January 2021). "Meralgia paresthetica treated by injection, decompression, and neurectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of pain and operative outcomes". J Neurosurg. 135 (3): 912–922. doi:10.3171/2020.7.JNS202191. PMID 33450741.

- ^ Lundborg G, Dahlin LB (May 1996). "Anatomy, function, and pathophysiology of peripheral nerves and nerve compression". Hand Clin. 12 (2): 185–93. PMID 8724572.

- ^ Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B (2020). "Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management". Pain Rep. 5 (4): e829. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000829. PMC 7382548. PMID 32766466.

- ^ Mackinnon SE (May 2002). "Pathophysiology of nerve compression". Hand Clin. 18 (2): 231–41. doi:10.1016/s0749-0712(01)00012-9. PMID 12371026.

- ^ Louie D, Earp B, Blazar P (September 2012). "Long-term outcomes of carpal tunnel release: a critical review of the literature". Hand (N Y). 7 (3): 242–6. doi:10.1007/s11552-012-9429-x. PMC 3418353. PMID 23997725.

- ^ Nickerson DS (2017). "Nerve decompression and neuropathy complications in diabetes: Are attitudes discordant with evidence?". Diabet Foot Ankle. 8 (1): 1367209. doi:10.1080/2000625X.2017.1367209. PMC 5613909. PMID 28959382.

- ^ Tu Y, Lineaweaver WC, Chen Z, Hu J, Mullins F, Zhang F (March 2017). "Surgical Decompression in the Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". J Reconstr Microsurg. 33 (3): 151–57. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1594300. PMID 27894152. S2CID 22825614.

- ^ Eccleston C, Hearn L, Williams AC (October 2015). "Psychological therapies for the management of chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (10): CD011259. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011259.pub2. PMC 6485637. PMID 26513427.

- ^ Boyd A, Bleakley C, Hurley DA, Gill C, Hannon-Fletcher M, Bell P, McDonough S (April 2019). "Herbal medicinal products or preparations for neuropathic pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (5): CD010528. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010528.pub4. PMC 6445324. PMID 30938843.

- ^ Ju ZY, Wang K, Cui HS, Yao Y, Liu SM, Zhou J, Chen TY, Xia J (December 2017). "Acupuncture for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (7): CD012057. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012057.pub2. PMC 6486266. PMID 29197180.

- ^ "Review of Diabetic Polyneuropathy: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis A".

- ^ Bartkoski S, Day M (2016-05-01). "Alpha-Lipoic Acid for Treatment of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy". American Family Physician. 93 (9): 786. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 27175957.

- ^ Grossman G (April 2008). "Neurological complications of coeliac disease: what is the evidence?". Practical Neurology. 8 (2): 77–89. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.139717. PMID 18344378. S2CID 28327166.

- ^ Sayad Fathi S, Zaminy A (September 2017). "Stem cell therapy for nerve injury". World Journal of Stem Cells. 9 (9): 144–151. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v9.i9.144. PMC 5620423. PMID 29026460.

- ^ Xu W, Cox CS, Li Y (2011). "Induced pluripotent stem cells for peripheral nerve regeneration". Journal of Stem Cells. 6 (1): 39–49. PMID 22997844.

- ^ Zhou JY, Zhang Z, Qian GS (2016). "Mesenchymal stem cells to treat diabetic neuropathy: a long and strenuous way from bench to the clinic". Cell Death Discovery. 2: 16055. doi:10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.55. PMC 4979500. PMID 27551543.

Further reading

edit- Latov N (2007). Peripheral Neuropathy: When the Numbness, Weakness, and Pain Won't Stop. New York: American Academy of Neurology Press Demos Medical. ISBN 978-1-932603-59-0.

- "Practice advisory for the prevention of perioperative peripheral neuropathies: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Prevention of Perioperative Peripheral Neuropathies". Anesthesiology. 92 (4): 1168–82. April 2000. doi:10.1097/00000542-200004000-00036. PMID 10754638.

External links

edit- Peripheral Neuropathy from the US NIH

- Peripheral Neuropathy at the Mayo Clinic