This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

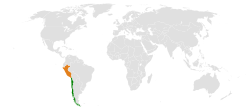

Chilean-Peruvian relations are the historical and current bilateral relations between the adjoining South American countries of the Republic of Chile and the Republic of Peru. Peru and Chile have shared diplomatic relations since at least the time of the Inca Empire in the 15th century. Under the Viceroyalty of Peru, Chile and Peru had connections using their modern names for the first time. Chile aided in the Peruvian War of Independence by providing troops and naval support.

| |

Chile |

Peru |

|---|---|

In the 19th century, as both countries became independent from Spain, Peru and Chile shared peaceful relations resulting from the formation of economic and political ties that further encouraged good relations. During the War of the Confederation (1836–1839), Chile and dissident Peruvians formed a military alliance to liberate and reunite the republics of South Peru and North Peru from the Peru-Bolivian Confederation. Later, during the Chincha Islands War (1864–1866), Peru and Chile led a united front against the Spanish fleet that occupied the Peruvian Chincha Islands and disrupted commerce in the South Pacific. In the 1870s, during the early conflicts prior to the War of the Pacific, Peru sought to negotiate a peaceful diplomatic solution between Bolivia and Chile. Although Peru had a secret defensive alliance with Bolivia,[1] Peru did not declare war on Chile even after Chile invaded the Bolivian port of Antofagasta. War was not declared formally until Chile declared war on both Peru and Bolivia in 1879. Peru declared war on Chile the following day. The war resulted in a Chilean invasion of Peru and the destruction of various Peruvian buildings, cities, a major raid and a two-year occupation of the capital of Peru, Lima. The ultimate result of the war left a deep scar on the three societies involved, and the relations between Peru and Chile soured for over a century, although relations were stabilized to some extent by the 1929 Treaty of Lima.

In 1975, the two countries were again on the brink of war, but armed conflict between left-wing Peru and right-wing Chile was averted. Relations remained tense due to alliances during and after the 1995 Cenepa War between Peru and Ecuador, but they have improved gradually, with the neighboring countries entering into new trade agreements in the 21st century.

History of diplomatic relations

editRule under the Spanish Empire

editAfter the conquest of Peru by Francisco Pizarro and his troops, Diego de Almagro went on an expedition to explore the lands of Chile that he had been assigned. After finding no gold and little more than farming societies and the fierce attacks of the Mapuche, Diego de Almagro returned to Peru with a broken army seeking to gain some sort of power and prestige. After attempting to overthrow Pizarro in Cusco, Diego de Almagro failed and was sentenced to death.

Some time after the events of Almagro, Pedro de Valdivia led an expedition from Peru to Chile, then called "Nuevo Toledo", that ended in the creation of Santiago de la Nueva Extremadura and the Captaincy General of Chile. The lack of the treasures and natural resources that the Spanish valued (such as gold and silver) for their economy and the constant raids from the local Mapuche made Chile a highly undesirable place. As a result, during the colonial era Chile was a poor and problematic province of the Viceroyalty of Peru, and it took a while before settlers would begin to find the other natural resources of the lands. In order to protect themselves from further attacks and full-scale revolts (such as the Arauco War), and retain official control of the lands, the Viceroyalty of Peru had to finance the defence of Chile by constructing extensive forts such as the Valdivian fort system.[2] In order to prevent other European nations from making colonies in these sparsely-populated areas, the trade of Chile became restricted to directly providing supplies, such as tallow, leather, and wine, to Peru. Moreover, a series of young officers in Chile made careers as governors of this territory, and a few even made it all the way to getting appointed viceroys of Peru (such as Ambrosio O'Higgins and Agustin de Jauregui y Aldecoa). This exchange of goods and supplies between both regions became the first recorded trade of both future nations.

Wars of Independence (1810–1830)

editA series of excellent historical relations followed these times, especially during this period of independence from Spain. From the start of the Spanish conquest, the Incas (and later their mestizo descendants) kept up the struggle for independence from Spain in the viceroyalty of Peru. A series of revolts by people such as Túpac Amaru II kept up the spirits for independence in Peru and the rest of South America. Nonetheless, Chile's remoteness greatly helped in making it become one of the first nations to declare independence with the so-called Patria Vieja. Even as this first attempt was thwarted by the Spanish, the spirit of independence continued in Chile. Later, with the aid of José de San Martín and the Argentine army, Chile once again became an independent nation. Meanwhile, Peru remained as a stronghold for the remaining Spanish forces whom sought to form a force large enough to re-conquer their lost territories. Jose de San Martin's army which included some Chilean soldiers marched into Lima and proclaimed the independence of Peru. Soon after that, more reinforcements arrived from the Peruvian population and commanders such as Ramon Castilla began to prove themselves as excellent tacticians. The arrival of Simón Bolívar and the subsequent victories at the battles of Junin and Ayacucho finally served as the end of Spanish rule in South America.

Afterwards, several of these war heroes helped in forming good relations between the newly formed nations as they became prominent politicians in their nations. People like Bernardo O'Higgins, Ramon Freire, Agustin Gamarra, and Ramon Castilla would often seek aid and refuge in either Peru or Chile. After the wars of independence, the mutual concerns of both nations mainly revolved around consolidating their nations as sovereign states. Peru and Chile found themselves in one of the friendliest of positions as they shared no territorial claims and also due to their historic trade. The cultures of both nations also kept close ties as the popular Peruvian Zamacueca evolved in Chile as the Cueca and in Peru as the yet-to-be named Marinera. Still, economic disputes and greed would soon destroy that which was apparently one of the best international relations in the world at that time.

Formation of Peru-Bolivia Confederation (1836)

editThe formation of large, united South American nations was a popular idea that Simón Bolívar and a series of other prominent leaders of that time sought to form. Nonetheless, the problems began when the leaders could not agree where the center of power of this union would be located. Many of the leaders would soon figure that this union would not happen, and many (such as José de San Martín) went back to their regular lives in disappointment. Yet, in order to expand his personal dream of Gran Colombia, Bolívar allowed Sucre to form the nation of Bolivia in Upper Peru. This action led to much controversy as the republican government of Peru sought to re-consolidate its power in a region that had belonged to them under the Spanish authorities. This period of time was filled with much political intrigue, and soon a war erupted between Peru and Gran Colombia. The political turmoil in Peru stopped Bolivar's plans to reach Bolivia and keep expanding Colombia, but the warfare ended indecisively. The aftermath of this left Peru consolidated as a state, Bolivia formally recognized as a separate entity by Peru, and the beginning of the dissolution of Gran Colombia into the nations of the New Granada (today, Colombia), Ecuador, and Venezuela.

Even though Peru had recognized the independence of Bolivia, the national sentiment among the Peruvian society and its politicians greatly influenced the events that would soon take place. Agustin Gamarra and Andres de Santa Cruz were the leading proponents of a union between these two nations during the 1830s, but each had different views on which nation would command the union. While Santa Cruz favored a Bolivian-led confederation, Gamarra sought to annex Bolivia into Peru. A series of political conflicts in Peru would soon give Santa Cruz the chance to start his plans, and led an invasion of Peru claiming his intentions were to restore order. A series of Peruvians felt betrayed by their own government as the president and several leaders of congress allowed Santa Cruz to divide Peru into two nations: North Peru and South Peru. The Peru-Bolivian Confederation was soon formed, and several leading powers of the day (Such as France and Great Britain) and the United States recognized the nation's existence. Politicians in South America would also form divided opinions about this new nation, but due to the political conflicts in the former states of the Greater Colombia, the main turmoil to this idea centered in Southern South America.

Among the most heavily involved in this situation was the Republic of Chile. Famous Chilean leaders such as Bernardo O'Higgins and Ramon Freire openly favored the ideas of the newly self-appointed "Grand Marshal" Santa Cruz, but at the same time they opposed the regime that at that moment governed Chile. The government in Chile was also deeply divided as to what they should do about this new nation. A series of Peruvians, including Agustin Gamarra and Ramon Castilla, saw the situation as an invasion of Bolivia into Peruvian territory, and they went into exile in Chile in order gain support from the Chilean government. Nevertheless, as far as things concerned Chile, Peru still owed a debt to the Chilean government as a result of this government helping in the liberation of Peru from Spain, and both nations were still under a commercial competition as to which port would become the most important in the southern Pacific coasts (Callao in Peru or Valparaíso in Chile). Moreover, Chile saw the creation of this new Peru-Bolivia government as a threat to Chilean independence and sovereignty due to the major influence that the combined territories of Peru and Bolivia were beginning to form in the world, and the many important Chilean figures exiled in Peru that sought to take over and change the current Chilean governmental administration. Even though the Peru-Bolivian Confederation was still very young, the economic and infrastructure plans of Grand Marshal Santa Cruz had made a major impact in the economy of Bolivia, and the nation of South Peru also began to greatly benefit as a result of being free from the control of Lima and staying under the economic policies of Santa Cruz. The only state from this union that did not truly benefit was North Peru, and soon this state would begin to provide the greatest support for Chilean intervention into this situation.

War of the Confederation (1836–1839)

editWhat eventually led Chile to form a liberation army (composed of Peruvians and Chileans) was the invasion of Chile by Chilean exiles in Peru-Bolivia under the leadership of Ramon Freire, who was under the support of Andres de Santa Cruz. The invasion of Freire failed, but the situation had escalated the bad relations between Peru-Bolivia and Chile. The first attack by the liberation army came without a declaration of war, and Santa Cruz was deeply offended by these actions that Chile was sponsoring. Nonetheless, in order to avoid war, Santa Cruz proposed a treaty of peace that would keep the relations between both nations at ease. Seeing this as a chance at formally setting forth a cause for war, Chile sent their ultimatum to Santa Cruz among which the dissolution of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation was included. Santa Cruz agreed to everything but the dissolution of the confederation, and Chile thus declared war upon the confederation. At the same time, the Argentine Confederation saw this as a chance to stop the meddling of Santa Cruz in northern Argentina and they also declared war upon Peru-Bolivia.

The first battles of the war were heavily disputed by both sides, but they mainly came in favor of Santa Cruz. Argentina's first major attempt also became their last as the northern provinces, whom were sympathetic of Santa Cruz, began a major revolt against the war. This left the combined forces of Chile and Peru alone in the war against Santa Cruz and his Peru-Bolivian troops (some under command of former Chilean officers such as Ramon Freire and even a French officer named Juan Blanchet). The first major attack of this liberation army also turned into a major disaster as the people of South Peru completely turned against this liberation force, and Santa Cruz persuaded the commander of these troops to sign a peace agreement confident that Chile would accept it as it stated (along several other things) that the debt of Peru to Chile would be repaid. In Chile, the war at first met much opposition from the Chilean society as they did not approve of the war. Still, after the assassination of an important political figure in Chile, the situation became a matter of national pride. In the Chilean congress, the votes turned against the peace treaty and several of the military officers that had lost at this first battle were court martialed.

The second campaign to attack Santa Cruz was better organized with excellent commanders such as the Chilean Manuel Bulnes Prieto and the Peruvian Ramon Castilla. This time they fought and eventually won an important victory in the Battle of Portada de Guias, and thus the liberation force was able to enter the city of Lima. Lima and the majority of the rest of North Peru met the liberation army with much approval, and even appointed Agustin Gamarra as provisional president. The victory was short-lived, though, as the liberation army retreated as they heard of a major army that would arrive soon under the command of Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, in the southern Pacific, a Confederate naval attack on Chile failed, but the victory was of mixed blessings as only one Confederate ship was sunk but the majority of the Chilean ships were badly and heavily damaged. Although Santa Cruz's army began to once again win a series of skirmishes and battles, a series of uprisings took the nation into instability. Santa Cruz could not be everywhere at once, and thus he decided to first finish the war with liberation forces and next deal with the insurrections. What came next was a surprising military defeat of the Confederate troops by the liberation forces as the Confederate forces began to split on opinions and the commanding skills of Manuel Bulnes Prieto proved superior to Santa Cruz, who was killed during the battle.

Following this, Peru was once again unified, and Agustin Gamarra attempted to lead an invasion to Bolivia. The attack utterly failed, Gamarra was killed, and Peru and Bolivia entered into another war. Bolivia would once again invade Peru but, without Gamarra, Ramon Castilla became the most prominent military figure of Peru and troops were soon dispatched for the defensive. The success in this defense resulted in Peruvian victories that returned both Peru and Bolivia to the former status quo. Although the relations between Peru and Bolivia would eventually find a "friendly point" in terms for the defense of both nations, Peru and Chile once again showed heavy improvements in their international relations as Peru soon paid back the Chilean assistance for this war and later in the past debt owed for the original liberation of Peru from Spain. The only major conflict between these nations became trade in the Pacific Ocean, but the lack of a land border left this topic solely as a commercial problem. As far as it concerned the Chilean society, Peru was the nation's closest ally against a possible invasion from Argentina; and as far as it concerned the Peruvian society, Chile had faithfully aided Peru in maintaining its independence. The political leadership of Ramon Castilla in Peru would further bring peaceful relations with Chile.

Chincha Islands War (1864–1866)

editThe first major intercontinental event involving these nations erupted as a result of guano, a resource that was heavily demanded in the international market and that western South America (mainly in the territories of Peru, Bolivia, and Chile) had plenty of to sell. The main problem arose out of Spain's belief that Peru was not an independent nation and that it was simply a rebellious state. This deeply angered Peru, but during those times the close ties among the Peruvians and their Spanish relatives did not amount to much trouble. In fact, when Spain sent a "scientific expedition" team to South America, the people of Chile and Peru greeted them with much cordiality. Nonetheless, for reasons not clear to this date, a fight broke out between two Spanish citizens a crowd of people in Lambayeque, Peru. The "scientific expedition" suddenly turned aggressive as they demanded the government of Peru to give reparations to the Spanish citizens and a government apology. The response of Peru was simple, according to the government the situation was an internal matter better left for the justice system and no apology was due. Without knowing it, this was the beginning of what would turn out to be a war.

As a result of this meeting, the Spanish expedition then made demands for Peru to pay its debt owed to Spain from the wars of independence. Peru was willing to negotiate, but when Spain sent a Royal Commissary instead of an ambassador, the government of Peru was deeply offended and soon diplomatic relations would turn for the worse. For Peru, a Royal Commissary was a custom that applied to the colony of another nation, while an ambassador was the appropriate title for a discussion among independent nations. Aside from this matter of technical names, due to the lack of good diplomacy between the Spanish envoy and the Peruvian minister of foreign affairs, the Spanish "scientific expedition" invaded the Chincha Islands (Rich in guano) of Peru just off the coast of the port of Callao. No war had been declared, but this action heavily deteriorated relations to a critical point. Meanwhile, the government of Chile sought to avoid a war with Spain and declared neutrality by officially denying provisions of armaments and fuel to Peru and Spain. Still, just as this order was put into effect two Peruvian steamers were heading out of Valparaíso with supplies, armaments, and Chilean volunteers. Although this was the only incident that went against the Chilean order, the Spanish fleet (no longer a scientific expedition) took it as a pretext to increase hostilities against Chile. Therefore, a week after refusing to salute the Spanish order to salute the Spanish flag by a gun salute, Chile declared war upon Spain.

The first battle of the war went in favor of Chile as the Spanish fleet suffered a humiliating defeat in the Battle of Papudo. Still, in order to achieve such a victory, Chile used the flag of Great Britain in order to ambush the Spanish fleet in Papudo. The Chileans captured the ship they attacked, the Covadonga, and kept it for use in the Chilean navy. In Peru, the situation was still stuck on the controversy over the occupation of the Chincha Islands. The lack of action eventually led to two Peruvian presidents to be overthrown until Mariano Ignacio Prado and the nationalist movement of Peru officially declared war against Spain and offered to aid Chile and form a united front against Spain. By this point, Chile was in much need of assistance as the Spanish fleet had begun its mobilization against the first nation who declared war upon them. Under a policy of punishment to the South American ports of the nations that had defied Spain, the Spanish fleet bombarded and destroyed the port and town of Valparaíso.

In Europe, the Spanish government was outraged at the Spanish fleet for it had defied orders to return to Spain before any blood was shed. Still, they did very little to stop the actions of Admiral Casto Méndez Núñez. The destruction of Valparaíso outraged several other South American nations including Ecuador and Bolivia (whom by this point had also declared war to Spain). Peru soon dispatched its fleet and admirals for the defense of Chile, and soon the Peruvian addition to the Chilean troops would make its mark as under the command of Peruvian admiral Manuel Villar the combined Peruvian and Chilean ships would effectively defend the Chiloe Archipelago from a Spanish bombardment or invasion. Prior to the battle, the Chilean and Peruvian ships had been waiting near the island of Chiloe for two Peruvian ships that were soon to arrive. The Spanish found out about this and dispatched their strongest ships to take care of this, and the ships of Chile and Peru were ambushed in Abtao (an island close to Chiloe). The Battle of Abtao thus took place, and although the result was inconclusive, the Spanish ships retreated after receiving heavy fire from the Peruvian ships Union and America.

Later, the Spanish fleet went to bombard and possibly invade Peru by giving a direct attack to the port of Callao. The port of Callao by that point had already received much aid from across South America, and the Peruvian defenders of Callao stood side by side with Chileans, Ecuadorians, and Bolivians. The Battle of Callao would prove to be another disaster for the Spanish fleet as the defenses of Callao proved stronger and defeated them to the point of forcing the complete retreat of the Spanish fleet from South American coasts. All the South American nations viewed the result favorably as Spain was not able to take control of any of the Guano-rich deposits. Still, the greed of guano would soon lead the former South American allies into a war that broke an alliance of nations that had proven stronger united than separated.

War of the Pacific (1879–1883)

edit-Tarapacá Department ceded by Peru to Chile in 1884.

-Puna de Atacama ceded by Bolivia/Chile to Argentina in 1889/1899

-Tarata occupied by Chile in 1885, return to Peru in 1925.

-Arica province occupied by Chile in 1884, ceded by Peru in 1929.

-Tacna (Sama River) occupied by Chile in 1884, return to Peru in 1929.

National borders in the region had never been definitively established; the two countries negotiated a treaty that recognized the 24th parallel south as their boundary and that gave Chile the right to share the export taxes on the mineral resources of Bolivia's territory between the 23rd and 24th parallels. But Bolivia subsequently became dissatisfied at having to share its taxes with Chile and feared Chilean seizure of its coastal region where Chilean interests already controlled the mining industry.

Peru's interest in the conflict stemmed from its traditional rivalry with Chile for hegemony on the Pacific coast. Also, the prosperity of the Peruvian government's guano (fertilizer) monopoly and the thriving nitrate industry in Peru's Tarapacá province were related to mining activities on the Bolivian coast.[3]

In 1873 Peru agreed secretly with Bolivia to a mutual guarantee of their territories and independence. In 1874 Chilean-Bolivian relations were ameliorated by a revised treaty under which Chile relinquished its share of export taxes on minerals shipped from Bolivia, and Bolivia agreed not to raise taxes on Chilean enterprises in Bolivia for 25 years. Amity was broken in 1878 when Bolivia tried to increase the taxes of the Chilean Antofagasta Nitrate Company over the protests of the Chilean government. When Bolivia threatened to confiscate the company's property, Chilean armed forces occupied the port city of Antofagasta on Feb. 14, 1879. Bolivia then imposed a presidential decree that confiscated all Chilean property in Bolivia and made a formal declaration of war on March 18, 1879.[4] The government of La Paz next called for Peruvian aid in accordance to the defensive alliance both nations had made in 1873, but Peru tried to negotiate a peaceful solution between Bolivia and Chile in order to avoid war. Chile, after finding out about the defensive alliance of Bolivia and Peru, demanded for Peru to remain neutral, and the Peruvian government decided to discuss both the Chilean and Bolivian proposal in a congressional meeting. However, becoming aware that Peru was actively mobilizing its armed forces while discussing peace, Chile declared war on both Bolivia and Peru on April 5, 1879.[5]

Chile easily occupied the Bolivian coastal region (Antofagasta province) and then took the offensive against Peru. Naval victories at Iquique (May 21, 1879) and Angamos (Oct. 8, 1879) enabled Chile to control the sea approaches to Peru. A Chilean army then invaded Peru. An attempt at mediation by the United States failed in October 1880, and Chilean forces occupied the Peruvian capital of Lima the following January.[6]

Chile was also to occupy the provinces of Tacna and Arica for 10 years, after which a plebiscite was to be held to determine their nationality. But the two countries failed for decades to agree on what terms the plebiscite was to be conducted. This diplomatic dispute over Tacna and Arica was known as the Question of the Pacific. Finally, in 1929, through the mediation of the United States, an accord was reached by which Chile kept Arica; Peru reacquired Tacna and received $6 million indemnity and other concessions.

During the war Peru suffered the loss of thousands of people and much property, and, at the war's end, a seven-month civil war ensued; the nation foundered economically for decades thereafter. In 1884 a truce between Bolivia and Chile gave the latter control of the entire Bolivian coast (Antofagasta province), with its nitrate, copper, and other mineral industries; a treaty in 1904 made this arrangement permanent. In return Chile agreed to build a railroad connecting the Bolivian capital of La Paz with the port of Arica and guaranteed freedom of transit for Bolivian commerce through Chilean ports and territory. But Bolivia continued its attempt to break out of its landlocked situation through the La Plata river system to the Atlantic coast, an effort that led ultimately to the Chaco War (1932–35) between Bolivia and Paraguay.[7]

In 1883, Chile and Peru signed the Treaty of Ancón in which Peru handed over the Province of Tarapacá. Peru also had to hand over the departments of Arica and Tacna. These would remain under Chilean control until a later date, when there would be a plebiscite to decide which nation would maintain control over Arica and Tacna. Chile and Peru, however, were unable to agree on how or when to hold the plebiscite, and in 1929, both countries signed the Treaty of Lima, in which Peru gained Tacna and Chile maintained control of Arica.

Military Regimes (1960s, 1970s)

editRelations remained sour because of the war. In 1975, both countries were on the brink of war, only a few years before the centennial of the War of the Pacific. The conflict was fueled by ideological disputes: Peruvian General Juan Velasco was a left-winger while Chilean General Augusto Pinochet was a right-winger. Velasco, backed by Cuba, set the date for invasion on August 6,[citation needed] the 150th independence anniversary of Bolivia, and the proposed date when Chile intended to grant this country with a sovereign corridor north of Arica, in former Peruvian territory, an action not approved by Peru. However, he was successfully dissuaded from starting the invasion on that date by his advisor, General Francisco Morales Bermúdez, whose original family was from the former Peruvian (currently Chilean) region of Tarapacá. Velasco later fell ill and was deposed by a group of generals who proclaimed Morales Bermúdez president on August 28.

Morales Bermúdez assured the Chilean government that Peru had no plans for an invasion. Tensions mounted again when a Chilean spy mission in Peru was discovered.[citation needed] Morales Bermúdez was again able to avert war, despite pressure from Velasco's ultranationalist followers.

Cenepa War controversy (1995)

editIn 1995, Peru was involved in the Cenepa War, a brief thirty-three-day war with Ecuador over the Cenepa River sector of the Cordillera del Condor territory in the western Amazon basin.[8] Chile, Argentina, Brazil, and the United States, as the guarantors of the 1942 Rio Protocol that had put an end to the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War earlier that century, worked with the governments of Peru and Ecuador to find a return to the status quo and end their border disputes once and for all. However, during the conflict, a series of Peruvian newspapers brought forth information claiming that Chile had sold armaments to Ecuador while the war was taking place.[9] This claim was promptly denied by Chile the following day on February 5, 1995, but admitted that they had sold weaponry to Ecuador on September 12, 1994, as part of a regular commercial exchange that had no aim against any particular nation. Due to lack of further information, Peru's president, Alberto Fujimori, put a momentary end to the scandal.[9]

However, the controversy was once again ignited when General Víctor Manuel Bayas, former Chief of Staff of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces during the Cenepa War, made a series of declarations in regards to the armed conflict between Peru and Ecuador. On March 21, 2005, General Bayas was asked by the Ecuadorian newspaper El Comercio if Chile had sold armaments to Ecuador during the Cenepa War, to which he replied: "Yes, it was a contract with the militaries during the conflict."[9] Furthermore, General Bayas revealed that Argentina and Russia had also sold weaponry to Ecuador during the conflict.[8] Later that same year, on April 11, Colonel Ernesto Checa, Ecuador's military representative in Chile during the Cenepa War, stated that Chile provided Ecuador with "ammunition, rifles and night vision devices" during the war.[9] Moreover, the Peruvian government revealed that it held knowledge that during the war at least a couple of Ecuadorian C-130 transport airplanes had landed in Chilean territory to pick up 9mm ammunition, and that the Ecuadorian Air Force had planned three more of those armament acquisition voyages to Chile. Nonetheless, the Peruvian government at that time regarded this as a minor incident due to the fact that the Chilean Sub-secretary of Foreign Relations told the Peruvian ambassador in Chile on February 2, 1995, that the Chilean government would take immediate measures to stop any other possible operations of this nature.[9]

In response to the declarations made by General Bayas, on March 22, 2005, the government of Chile denied the claims and stated that the only registered sale of weapons to Ecuador was in 1994. Jaime Ravinet, the Chilean Minister of Defense, assured that any other armament transfer after the 1994 date had been illegal. Ravinet further stated that, after discussing the matter with his Peruvian counterpart, Roberto Chiabra, the situation had been resolved.[8] Yet, the Peruvian government did not find the February 5, 1995, and March 22, 2005, declarations as acceptable or sufficient; and went on to send a note of protest to the Chilean government. Peru added that Chile, as a guarantor of the Rio Protocol, should have maintained absolute neutrality and that this alleged weapons commerce during the Cenepa War goes against resolutions made by the United Nations and the Organization of American States.[8][9]

Edwin Donayre (2008)

editDonayre became the center of an international controversy on November 24, 2008, when Peruvian media showed a YouTube video in which the general said "We are not going to let Chileans pass by (...) [A] Chilean who enters will not leave. Or will leave in a coffin. And if there aren't sufficient coffins, there will be plastic bags". The video, dated to 2006 or 2007, was recorded during a party at a friend's house attended by army officials and civilians. These comments caused widespread indignation in Chile, making headlines in the El Mercurio newspaper. The Peruvian president, Alan García, called his Chilean counterpart, Michelle Bachelet, to explain that these remarks did not reflect official Peruvian policy. Bachelet declared herself satisfied with the explanations.[10]

On November 28, in response to this incident, a Chilean government spokesman stated that a scheduled visit to Chile by the Peruvian defense minister, Antero Flores Aráoz, might be inopportune given the circumstances. The following day, Flores Aráoz announced his decision to postpone his trip after conferring with the Foreign Affairs Minister, José Antonio García Belaúnde. Several members of the Peruvian government commented on the spokesman's remarks including president García who said the country "did not accept pressure or orders from anybody outside of Peru".[11] Donayre defended the video, declaring that Peruvian citizens have a right to say whatever they want at private gatherings and that even though he is scheduled to retire on December 5 he will not be forced to resign early under external pressure. As a consequence of these exchanges, tensions between Peru and Chile rose again; president Bachelet met with top aides on December 1 to discuss the matter and possible courses of action. Meanwhile, in Lima, Congressman Gustavo Espinoza became the center of attention as the main suspect of leaking the video to Chilean press and politicians.[12] Donayre ended his tenure as Commanding General of the Army on December 5, 2008, as expected; president Alan García appointed General Otto Guibovich as his replacement.[13]

Maritime dispute (2008–2014)

editRelations between the two nations have since mostly recovered. In 2005, the Peruvian Congress unilaterally approved a law which increased the stated sea limit with Chile. This law superseded the Peruvian supreme decree 781 for same purpose from 1947, which had automatically limited its maritime border to geographical parallels only. Peru's position was that the border has never been fully demarcated, but Chile disagreed reminding on treaties in 1952 and 1954 between the countries, which supposedly defined sea border. The border problem has still not been solved. However, Chile's Michelle Bachelet and Peru's Alan García have established a positive diplomatic relationship, and it is very unlikely any hostilities will break out because of the dispute.

On January 26, 2007, Peru's government issued a protest against Chile's demarcation of the coastal frontier the two countries share. According to the Peruvian Foreign Ministry, the Chilean legislatures had endorsed a plan regarding the Arica and Parinacota region which did not comply with the current established territorial demarcation. Moreover, it is alleged that the proposed Chilean law included an assertion of sovereignty over 19,000 sq. meters of land in Peru's Tacna Region. According to the Peruvian Foreign Ministry, Chile has defined a new region "without respecting the Concordia demarcation."

The Chilean deputies and senators that approved the law said they did not notice this error.[citation needed] For its part, the Chilean government has asserted that the region in dispute is not a coastal site named Concordia, but instead refers to boundary stone No. 1, which is located to the northeast and 200 meters inland. A possible border dispute was averted when the Chilean Constitutional Court formally ruled on January 26, 2007, against the legislation. While agreeing with the court's ruling, the Chilean government reiterated its stance that the maritime borders between the two nations were not in question and have been formally recognized by the international community.

Nevertheless, in early April 2007, Peruvian nationalistic sectors, mainly represented by left wing ex-presidential candidate Ollanta Humala decided to congregate at 'hito uno' right at the border with Chile, in a symbolic attempt to claim sovereignty over a maritime area known in Peru as Mar de Grau (Grau's Sea) just west of the Chilean city of Arica. Peruvian police stopped a group of nearly 2,000 people just 10 km from the border, preventing them from reaching their intended destination. Despite these incidents, the presidents of both Chile and Peru have confirmed their intentions to improve the relationships between the two countries, mainly fueled by the huge amount of commercial exchange between both countries' private sectors.

In 2007 the Chilean government decided, as a sign of goodwill, to voluntarily return thousands of historical books plundered from Lima's National Library during the Chilean occupation of Peru.[14] Peru is still looking for other cultural items to be brought back home.

On January 16, 2008, Peru formally presented the case to the International Court of Justice, in which the Peruvian government sued the state of Chile regarding the Chilean-Peruvian maritime dispute of 2006–2007. The court is expected to reach a verdict in no less than 7 years.[15]

In 2011, prior to new Peruvian President Ollanta Humala's visit to Bolivia in his pre-inauguration Pan-Americas tour, Peru agreed to cede territory claimed by Bolivia against Chile so as to facilitate resolution of the maritime claim. The 1929 Peace and Friendship treaty, which formalized relations between the three states following the War of the Pacific, requires Peru's "prior agreement" to pursue further negotiations for Chile to cede former Peruvian territory to a third party and settle the conflict.[16]

Recent history

editIn late 2009, Chile continued a multi-national military exercise dubbed Salitre II 2009,[17] which concerned the Peruvian government due to the planned scenario of a northern country attacking a southern country (Both Peru and Bolivia are the northern neighbors of Chile; and both Peru and Chile are expecting to receive a formal decision from the International Court of Justice). However, Chile eventually modified the scenario in order to deal with a dictator in a foreign continent.[18] Airmen from Argentina, Brazil, France and the United States participated in the exercise.[19] Afterwards, Peru's Chancellor José Antonio García Belaúnde expressed the Peruvian government's decision to neither attend the event or make any further comments on this internal affair of Chile.[20][21] Nonetheless, upon the event's conclusion, Chilean congressman Jorge Tarud stated that the military exercise was a "loss for Peru" based on the idea that Peru used its full diplomatic force in order to prevent the event from taking place. Tarud also added that this was not an offensive exercise but for the maintenance of peace.[21] Yet, Peru's major diplomatic action during this time was its proposal to create a non-aggression pact among all South American nations and to prevent further increase in weaponry from the nations of South America, which Tarud considered to be aimed at Chile.[22]

In November 2009 Peru detained a low-ranking air force officer on suspicion of treason for allegedly spying for Chile. Peru cited the incident as its reason for quitting the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Singapore early that month. Chile has rejected the spying accusations and accused Garcia of overreacting. Chilean officials suggested he timed the espionage revelation to create a scandal at the summit where leaders were holding talks on regional integration.[23]

In 2014, the International Court of Justice resolved the Chilean-Peruvian Maritime Dispute of 2006, demarcating the sea border line between the two nations.[24][25]

Both nations are members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Organization of Ibero-American States, Organization of American States, Pacific Alliance, Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, Rio Group and the United Nations.

Trade relations

editThe Peru-Chile Free Trade Agreement entered into force on 1 March 2009.

Resident diplomatic missions

edit- Chile has an embassy in Lima and consulates-general in Arequipa and Tacna.[26][27]

- Peru has an embassy in Santiago de Chile and consulates-general in Arica and Iquique.[28]

-

Embassy of Chile in Lima

-

Embassy of Peru in Santiago

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "War of the Pacific - South American history - Britannica.com". britannica.com. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Breve Historia de Valdivia". Editorial Francisco Vigil. Archived from the original on 2007-02-18.

- ^ Shepherd, W.R. (1919). The Hispanic Nations of the New World: A Chronicle of Our Southern Neighbors. Vol. 50. Yale University Press. p. 137. ISBN 9781465535702. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific" Sater, 2007"

- ^ "Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific" Sater, 2007

- ^ Farcau, B.W. (2000). The Ten Cents War: Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Praeger. ISBN 9780275969257. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Armed Conflict Year Index". onwar.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Chile niega haber vendido armas a Ecuador antes del conflicto con Perú en 1995". clarin.com. 22 March 2005. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores del Perú - Portal Institucional". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ CNN, Peru leader rejects top general's remarks on Chile, November 26, 2008. Retrieved on December 3, 2008.

- ^ Reuters, Peru leader rejects top general's remarks on Chile, November 29, 2008. Retrieved on December 3, 2008.

- ^ CNN, Chileans angry over Peru general's 'body bag' remark, December 1, 2008. Retrieved on December 3, 2008.

- ^ Living in Peru, Peru appoints new army chief, replaces Donayre, December 5, 2008. Retrieved on December 6, 2008.

- ^ "Chile concreta devolución de miles de libros a Biblioteca de Lima". emol.com. 5 November 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Perú demanda a Chile ante la Corte de la Haya por diferencias en los límites marítimos - Internacional - EL PAÍS". El País. elpais.com. 16 January 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Bolivia Weekly - Humala Visits Burnt Palace; Morales Expected to Discuss Pacific Access". Archived from the original on 2011-07-02. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ http://salitre2009.fach.cl/inglish_salitre/what_is.htm[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Chile admite que sí conversó con EEUU para cambiar ejercicio militar "Salitre 2009"". Archived from the original on 2009-10-23. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "Embassy News 2009 - Santiago, Chile - Embassy of the United States". chile.usembassy.gov. Archived from the original on February 20, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Al Perú no le preocupan ejercicios militares "Salitre 2009" realizados en Chile, afirma su canciller". Archived from the original on 2009-10-23. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ a b "Diputado chileno Jorge Tarud: "Ejercicio militar Salitre 2009 es una derrota del Perú porque quiso que se cayera"". Archived from the original on 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "Diputado chileno Jorge Tarud: "Perú inició una campaña de desprestigio contra Chile"". Archived from the original on 2009-10-26. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "Peru's Garcia calls on Chile to explain spy case". Reuters. November 16, 2009. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ CORDER, MIKE (27 January 2014). "World court draws new Peru-Chile maritime border". ap.org. Associated Press. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Peru insiste en levantar un conflicto por el mar". estrellaiquique.cl. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ Embassy of Chile in Lima

- ^ Consulates of Chile in Peru

- ^ Embassy of Peru in Santiago