This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

The piastre or piaster (English: /piˈæstər/) is any of a number of units of currency. The term originates from the Italian for "thin metal plate". The name was applied to Spanish and Hispanic American pieces of eight, or pesos, by Venetian traders in the Levant in the 16th century.

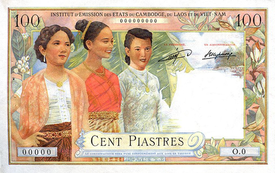

These pesos, minted continually for centuries, were readily accepted by traders in many parts of the world. After the countries of Latin America had gained independence, pesos of Mexico began flowing in through the trade routes, and became prolific in the Far East, taking the place of the Spanish pieces of eight which had been introduced by the Spanish at Manila, and by the Portuguese at Malacca. When the French colonised Indochina, they began issuing the new French Indochinese piastre (piastre de commerce), which was equal in value to the familiar Spanish and Mexican pesos.

In the Ottoman Empire, the word piastre was a colloquial European name of Kuruş. Successive currency reforms had reduced the value of the Ottoman piastre by the late 19th century so as to be worth about two pence (2d) sterling. Hence the name piastre referred to two distinct kinds of coins in two distinct parts of the world, both of which had descended from the Spanish pieces of eight.

Because of the debased values of the piastres in the Middle East, these piastres became subsidiary units for the Turkish, Lebanese, Cypriot, and Egyptian pounds.[1] Meanwhile, in Indochina, the piastre continued into the 1950s and was subsequently renamed the riel, the kip, and the dong in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam respectively.

As a main unit

editAs a sub-unit

edit- 1⁄100 of the Egyptian pound

- 1⁄100 of the Jordanian dinar

- 1⁄100 of the Lebanese pound

- 1⁄100 of the South Sudanese pound (spelled "piaster")

- 1⁄100 of the Sudanese pound

- 1⁄100 of the Syrian pound

Obsolete currencies

edit- 1⁄180 of the Cypriot pound

- 1⁄100 of the Libyan pound

- 1⁄100 of the Turkish lira

Other usage

editEarly private bank currency issues in French-speaking regions of Canada were denominated in piastres, and the term continued in official use for some time as a term for the Canadian dollar. For example, the original French version of the 1867 Constitution of Canada refers to a requirement that senators hold property d'une valeur de quatre mille piastres.

The term is still unofficially used in Quebec, Acadian, Franco-Manitoban, and Franco-Ontarian language as a reference to the Canadian dollar, much as English speakers say "bucks." (The official French term for the modern Canadian dollar is dollar.) When used colloquially in this way, the term is often pronounced and spelled "piasse" (pl. "piasses"). It was equivalent to 6 New France livres or 120 sous, a quarter of which was "30 sous", which is also still in slang use when referring to 25 cents.

Piastre was also the original French word for the United States dollar, used for example in the French text of the Louisiana Purchase. Calling the US dollar a piastre is still common among speakers of Cajun French and New England French. Modern French uses dollar for this unit of currency as well. The term is still used as slang for US dollars in the French-speaking Caribbean islands, most notably Haiti.

Piastre is another name for kuruş, 1⁄100 of the Turkish lira.

The piastre is still used in Mauritius when bidding in auction sales, similarly to the way that guineas are used at British racehorse auctions. It is equivalent to 2 Mauritian rupees.[2]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Thimm, Carl Albert. "Egyptian Money". Egyptian Self-Taught. William Brown & Co., Ltd., St. Mary Axe, London, E.C.

- ^ MD, Michael J. Aminoff (24 November 2010). Brown-Sequard: An Improbable Genius Who Transformed Medicine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-978064-8 – via Google Books.

Further reading

editEckfeldt, Jacob Reese; Du Bois, William Ewing; Saxton, Joseph (1842). A manual of gold and silver coins of all nations, struck within the past century. Showing their history, and legal basis, and their actual weight, fineness, and value chiefly from original and recent assays. With which are incorporated treatises on bullion and plate, counterfeit coins, specific gravity of precious metals, etc., with recent statistics of the production and coinage of gold and silver in the world, and sundry useful tables. Assay Office of the Mint. p. 132.