This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

The picaresque novel (Spanish: picaresca, from pícaro, for 'rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but "appealing hero", usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrupt society.[1] Picaresque novels typically adopt the form of "an episodic prose narrative"[2] with a realistic style. There are often some elements of comedy and satire. Although the term "picaresque novel" was coined in 1810, the picaresque genre began with the Spanish novel Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), which was published anonymously during the Spanish Golden Age because of its anticlerical content. Literary works from Imperial Rome published during the 1st–2nd century AD, such as Satyricon by Petronius and The Golden Ass by Apuleius had a relevant influence on the picaresque genre and are considered predecessors. Other notable early Spanish contributors to the genre included Mateo Alemán's Guzmán de Alfarache (1599–1604) and Francisco de Quevedo's El Buscón (1626). Some other ancient influences of the picaresque genre include Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence. The Golden Ass by Apuleius nevertheless remains, according to different scholars such as F. W. Chandler, A. Marasso, T. Somerville and T. Bodenmüller, the primary antecedent influence for the picaresque genre.[3] Subsequently, following the example of Spanish writers, the genre flourished throughout Europe for more than 200 years and it continues to have an influence on modern literature and fiction.

Defined

editAccording to the traditional view of Thrall and Hibbard (first published in 1936), seven qualities distinguish the picaresque novel or narrative form, all or some of which an author may employ for effect:[4]

- A picaresque narrative is usually written in first person as an autobiographical account.

- The main character is often of low character or social class. They get by with wits and rarely deign to hold a job.

- There is little or no plot. The story is told in a series of loosely connected adventures or episodes.

- There is little if any character development in the main character. Once a pícaro, always a pícaro. Their circumstances may change but these rarely result in a change of heart.

- The pícaro's story is told with a plainness of language or realism.

- Satire is sometimes a prominent element.

- The behavior of a picaresque protagonist stops just short of criminality. Carefree or immoral rascality positions the picaresque hero as a sympathetic outsider, untouched by the false rules of society.

In the English-speaking world, the term "picaresque" is often used loosely to refer to novels that contain some elements of this genre; e.g. an episodic recounting of adventures on the road.[5] The term is also sometimes used to describe works which only contain some of the genre's elements, such as Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605 and 1615), or Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers (1836–1837).

Etymology

editThe word pícaro first starts to appear in Spain with the current meaning in 1545, though at the time it had no association with literature.[6] The word pícaro does not appear in Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), the novella credited by modern scholars with founding the genre. The expression picaresque novel was coined in 1810.[7][8] Whether it has any validity at all as a generic label in the Spanish sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—Cervantes certainly used "picaresque" with a different meaning than it has today—has been called into question. There is unresolved debate within Hispanic studies about what the term means, or meant, and which works were, or should be, so called. The only work clearly called "picaresque" by its contemporaries was Mateo Alemán's Guzmán de Alfarache (1599–1604), which they considered "El libro del pícaro" (English: "The Book of the Pícaro").[9]

History

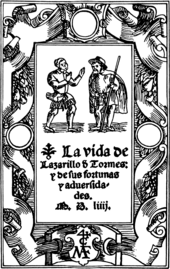

editLazarillo de Tormes and its sources

editWhile elements of literature by Geoffrey Chaucer and Giovanni Boccaccio have a picaresque feel and may have contributed to the style,[10] the modern picaresque begins with Lazarillo de Tormes,[11] which was published anonymously in 1554 in Burgos, Medina del Campo, and Alcalá de Henares in Spain, and also in Antwerp, which at the time was under Spanish rule as a major city in the Spanish Netherlands. It is variously considered either the first picaresque novel or at least the antecedent of the genre.

The protagonist, Lázaro, lives by his wits in an effort to survive and succeed in an impoverished country full of hypocrisy. As a pícaro character, he is an alienated outsider, whose ability to expose and ridicule individuals compromised within society gives him a revolutionary stance.[12] Lázaro states that the motivation for his writing is to communicate his experiences of overcoming deception, hypocrisy, and falsehood (engaño).[13]

The character type draws on elements of characterization already present in Roman literature, especially Petronius' Satyricon. Lázaro shares some of the traits of the central figure of Encolpius, a former gladiator,[14][15] though it is unlikely that the author had access to Petronius' work.[16] From the comedies of Plautus, Lazarillo borrows the figure of the parasite and the supple slave. Other traits are taken from Apuleius' The Golden Ass.[14] The Golden Ass and Satyricon are rare surviving samples of the "Milesian tale", a popular genre in the classical world, and were revived and widely read in Renaissance Europe.

The principal episodes of Lazarillo are based on Arabic folktales that were well known to the Moorish inhabitants of Spain. The Arabic influence may account for the negative portrayal of priests and other church officials in Lazarillo.[17] Arabic literature, which was read widely in Spain in the time of Al-Andalus and possessed a literary tradition with similar themes, is thus another possible influence on the picaresque style. Al-Hamadhani (d.1008) of Hamadhan (Iran) is credited with inventing the literary genre of maqāmāt in which a wandering vagabond makes his living on the gifts his listeners give him following his extemporaneous displays of rhetoric, erudition, or verse, often done with a trickster's touch.[18] Ibn al-Astarkuwi or al-Ashtarkuni (d.1134) also wrote in the genre maqāmāt, comparable to later European picaresque.[19]

The curious presence of Russian loanwords in the text of the Lazarillo also suggests the influence of medieval Slavic tales of tricksters, thieves, itinerant prostitutes, and brigands, who were common figures in the impoverished areas bordering on Germany to the west. When diplomatic ties to Germany and Spain were established under the emperor Charles V, these tales began to be read in Italian translations in the Iberian Peninsula.[20]

As narrator of his own adventures, Lázaro seeks to portray himself as the victim of both his ancestry and his circumstance. This means of appealing to the compassion of the reader would be directly challenged by later picaresque novels such as Guzmán de Alfarache (1599/1604) and El Buscón (composed in the first decade of the 17th century and first published in 1626) because the idea of determinism used to cast the pícaro as a victim clashed with the Catholic Revival doctrine of free will.[21]

Other initial works

editAn early example is Mateo Alemán's Guzmán de Alfarache (1599), characterized by religiosity. Guzmán de Alfarache is a fictional character who lived in the city of San Juan de Aznalfarache, in Seville, Spain.

Francisco de Quevedo's El Buscón (1604 according to Francisco Rico; the exact date is uncertain, yet it was certainly a very early work) is considered the absolute masterpiece of the genre by A. A. Parker, because of his baroque style and the study of delinquent psychology. However, a different school of thought, led by Francisco Rico, rejects Parker's view, contending instead that the protagonist, Don Pablos, is a unrealistic character, simply a means for Quevedo to launch classist, racist and sexist attacks. Moreover, argues Rico, the structure of the novel is radically different from previous works of the picaresque genre: Quevedo uses the conventions of the picaresque as a mere vehicle to show off his abilities with conceit and rhetoric, rather than to construct a satirical critique of Spanish Golden Age society.

Miguel de Cervantes wrote several works "in the picaresque manner, notably Rinconete y Cortadillo (1613) and El coloquio de los perros (1613; "Colloquy of the Dogs")". "Cervantes also incorporated elements of the picaresque into his greatest novel, Don Quixote (1605, 1615)",[22] the "single most important progenitor of the modern novel", that M. H. Abrams has described as a "quasi-picaresque narrative".[23] Here the hero is not a rogue but a foolish knight.

In order to understand the historical context that led to the development of these paradigmatic picaresque novels in Spain during the 16th and 17th centuries, it is essential to take into consideration the circumstances surrounding the lives of conversos, whose ancestors had been Jewish, and whose New Christian faith was subjected to close scrutiny and mistrust.[24]

The Spanish novels were read and imitated in other European countries where their influence can be found. In Germany, Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen wrote Simplicius Simplicissimus[25] (1669), considered the most important of non-Spanish picaresque novels. It describes the devastation caused by the Thirty Years' War. Grimmelshausen's novel has been called an example of the German abenteuerroman (which literally means "adventure novel"). An abenteuerroman is Germany's version of the picaresque novel; it is an "entertaining story of the adventures of the hero, but there is also often a serious aspect to the story."[26]

Alain-René Le Sage's Gil Blas (1715) is a classic example of the genre,[27] which in France had declined into an aristocratic adventure.[citation needed] In Britain, the first example is Thomas Nashe's The Unfortunate Traveller (1594) in which a court page, Jack Wilson, exposes the underclass life in a string of European cities through lively, often brutal descriptions.[28] The body of Tobias Smollett's work, and Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders (1722) are considered picaresque, but they lack the sense of religious redemption of delinquency that was very important in Spanish and German novels. The triumph of Moll Flanders is more economic than moral. While the mores of the early 18th century wouldn't permit Moll to be a heroine per se, Defoe hardly disguises his admiration for her resilience and resourcefulness.

Works with some picaresque elements

editThe autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, written in Florence beginning in 1558, also has much in common with the picaresque.

The classic Chinese novel Journey to the West is considered to have considerable picaresque elements. Having been published in 1590, it is contemporary with much of the above—but is unlikely to have been directly influenced by the European genre.

18th and 19th centuries

editHenry Fielding proved his mastery of the form in Joseph Andrews (1742), The Life and Death of Jonathan Wild, the Great (1743) and The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749), though Fielding attributed his style to an "imitation of the manner of Cervantes, author of Don Quixote".[29]

William Makepeace Thackeray is the master of the 19th-century English picaresque. His best-known work, Vanity Fair: A Novel Without a Hero (1847–1848) — a title ironically derived from John Bunyan's Puritan allegory of redemption The Pilgrim's Progress (1678) — follows the career of fortune-hunting adventuress Becky Sharp, her progress echoing the earlier Moll Flanders. His earlier novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844) recounts the rise and fall of an Irish arriviste conniving his way into the 18th-century English aristocracy.

The 1880 Romanian novella Ivan Turbincă tells the story of a kind, but hedonistic and scheming ex soldier who ends up tricking God, the Devil, and the Grim Reaper so that he can sneak into Heaven to party forever.

Aleko Konstantinov wrote the 1895 novel Bay Ganyo about the eponymous Bulgarian rogue. The character conducts business of uneven honesty around Europe before returning home to get into politics and newspaper publishing. Bay Ganyo is a well-known stereotype in Bulgaria.

Works influenced by the picaresque

editIn the English-speaking world, the term "picaresque" has referred more to a literary technique or model than to the precise genre that the Spanish call picaresco. The English-language term can simply refer to an episodic recounting of the adventures of an anti-hero on the road.[30]

Laurence Sterne's The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1761–1767) and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1768) each have strong picaresque elements. Voltaire's satirical novel Candide (1759) contains elements of the picaresque. An interesting variation on the tradition of the picaresque is The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan (1824), a satirical view on early 19th-century Persia, written by James Morier. Another novel on the same theme is A Rogue's Life (1857) by Wilkie Collins.

Elements[clarification needed] of the picaresque novel are found in Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers (1836–37).[31] Nikolai Gogol occasionally used the technique, as in Dead Souls (1842–52).[32] Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) also has some elements of the picaresque novel.[31]

20th and 21st centuries

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

Kvachi Kvachantiradze is a novel by Mikheil Javakhishvili published in 1924. This is, in brief, the story of a swindler, a Georgian Felix Krull, or perhaps a cynical Don Quixote, named Kvachi Kvachantiradze: womanizer, cheat, perpetrator of insurance fraud, bank-robber, associate of Rasputin, filmmaker, revolutionary, and pimp.

The Twelve Chairs (1928) and its sequel, The Little Golden Calf (1931), by Ilya Ilf and Yevgeni Petrov (together known as Ilf and Petrov) became classics of 20th-century Russian satire and the basis for numerous film adaptations.

Camilo José Cela's The Family of Pascual Duarte (1942),[33] Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man (1952) and The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow (1953) were also among mid-twentieth-century picaresque literature.[34] John A. Lee's Shining with the Shiner (1944) tells amusing tales about New Zealand folk hero Ned Slattery (1840–1927) surviving by his wits and beating the 'Protestant work ethic'. So too is Thomas Mann's Confessions of Felix Krull (1954), which like many novels emphasizes the theme of a charmingly roguish ascent in the social order. Under the Net (1954) by Iris Murdoch,[35] Günter Grass's The Tin Drum (1959) is a German picaresque novel. John Barth's The Sot-Weed Factor (1960) is a picaresque novel that parodies the historical novel and uses black humor by intentionally incorrectly using literary devices.[26]

Other examples from the 1960s and 1970s include Jerzy Kosinski's The Painted Bird (1965), Vladimir Voinovich's The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin (1969), and Arto Paasilinna's The Year of the Hare (1975).

Examples from the 1980s include John Kennedy Toole's novel A Confederacy of Dunces, which was published in 1980, eleven years after the author's suicide, and won the 1981 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. It follows the adventures of Ignatius J. Reilly, a well-educated but lazy and obese slob, as he attempts to find stable employment in New Orleans and meets many colorful characters along the way.

Later examples include Umberto Eco's Baudolino (2000),[36] and Aravind Adiga's The White Tiger (Booker Prize 2008).[37]

William S. Burroughs was a devoted fan of picaresque novels, and gave a series of lectures involving the topic in 1979 at Naropa University in Colorado. He says it is impossible to separate the anti-hero from the picaresque novel, that most of these are funny, and they all have protagonists who are outsiders by their nature. His list of picaresque novels includes Petronius' novel Satyricon (54–68 AD), The Unfortunate Traveller (1594) by Thomas Nashe, both Maiden Voyage (1943) and A Voice Through a Cloud (1950) by Denton Welch, Two Serious Ladies (1943) by Jane Bowles, Death on Credit (1936) by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, and even himself.[38]

In contemporary Latin American literature, there are Manuel Rojas' Hijo de ladrón (1951), Joaquín Edwards' El roto (1968), Elena Poniatowska's Hasta no verte Jesús mío (1969), Luis Zapata's Las aventuras, desventuras y sueños de Adonis García, el vampiro de la colonia Roma (1978) and José Baroja's Un hijo de perra (2017), among others.[39]

Works influenced by the picaresque

edit- Jaroslav Hašek's The Good Soldier Švejk (1923) is an example of a work from Central Europe that has picaresque elements.[40]

- J. B. Priestley made use of the form in his The Good Companions (1929), which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction.

- Fritz Leiber's sword and sorcery series of novels, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, are considered to have many picaresque elements, and are sometimes described as picaresque on the whole.[41][42][43][44]

- Hannah Tinti's novel The Good Thief (2008) features a young, one-handed orphan who craves a family, and finds one in a group of rogues and misfits.

In cinema

editIn 1987 an Italian comedy film written and directed by Mario Monicelli was released under the Italian title I picari. It was co-produced with Spain, where it was released as Los alegres pícaros,[45] and internationally as The Rogues. Starring Vittorio Gassman, Nino Manfredi, Enrico Montesano, Giuliana De Sio and Giancarlo Giannini, the film is freely inspired by the Spanish novels Lazarillo de Tormes and Guzman de Alfarache.[46] The Disney film Aladdin (1992) can be considered a picaresque story.[47]

In television

editThe sixth episode of Season 1 of the Spanish fantasy television series, El ministerio del tiempo (English title: The Ministry of Time), entitled "Tiempo de pícaros" (Time of rascals) focuses on Lazarillo de Tormes as a young boy prior to his adventures in the genre-creating novel that bears his name. The Netflix series Inventing Anna (2022) has been called "somewhat anhedonic post-internet picaresque". [48]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Canton, James; Cleary, Helen; Kramer, Ann; Laxby, Robin; Loxley, Diana; Ripley, Esther; Todd, Megan; Shaghar, Hila; Valente, Alex (2016). The Literature Book. New York: DK. p. 342. ISBN 978-1-4654-2988-9.

- ^ Ricapito, Joseph V. (1978). "The Golden Ass of Apuleius and the Spanish Picaresque Novel". Revista Hispánica Moderna. 40 (3/4). University of Pennsylvania Press: 77–85. JSTOR 30203173.

- ^ Thrall, William and Addison Hibbard. A Handbook to Literature. The Odyssey Press, New York. 1960.

- ^ "picaresque". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Best, O. F. "Para la etimología de pícaro". IN: Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, Vol. 17, No. 3/4 (1963/1964), pp. 352–357.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, p. 936. Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- ^ Rodríguez González, Félix (1996). Spanish Loanwords in the English Language: a tendency towards hegemony reversal, p. 36. Walter de Gruyter. Google Books.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel [in Spanish] (1979). "Does the Picaresque Novel Exist?" (PDF). Kentucky Romance Quarterly. Vol. 26. pp. 203–219. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2019.

- ^ Seán Ó Neachtain (2000). The History of Éamon O'Clery. Clo Iar-Chonnacht. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-902420-35-6. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Turner, Harriet; López de Martínez, Adelaida (11 September 2003). The Cambridge Companion to the Spanish Novel: From 1600 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-521-77815-2. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Cruz, Anne J. (2008). Approaches to teaching Lazarillo de Tormes and the picaresque tradition, p. 19. ("The pícaro's revolutionary stance, as an alienated outsider who nevertheless constructs his own self and his world").

- ^ MacAdam, Alfred J. Textual confrontations: comparative readings in Latin American literature, p. 138. Google Books.

- ^ a b Chaytor, Henry John (1922)La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes p. vii.

- ^ The life of Lazarillo de Tormes: his fortunes and adversities (1962) p. 18.

- ^ Martin, René (1999) Le Satyricon: Pétrone, p. 105. Google Books.

- ^ Fouad Al-Mounir, "The Muslim Heritage of Lazarillo de Tormes," The Maghreb Review vol. 8, no. 2 (1983), pp. 16–17.

- ^ James T. Monroe, The art of Badi'u 'l-Zaman al-Hamadhani as picaresque narrative (American University of Beirut c1983).

- ^ Monroe, James T. translator, Al-Maqamat al-luzumiyah, by Abu-l-Tahir Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Tamimi al-Saraqus'i ibn al-Astarkuwi. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

- ^ S. Rodzevich, "K istorii russkogo romantizma", Russky Filologichesky Vestnik, 77 (1917), 194–237 (in Russian).

- ^ Boruchoff, David A. (2009). "Free Will, the Picaresque, and the Exemplarity of Cervantes's Novelas ejemplares". MLN. 124 (2): 372–403. doi:10.1353/mln.0.0121. JSTOR 29734505. S2CID 162205817.

- ^ "Picaresque", Britannica online

- ^ A Glossary of Literary Terms (7th ed.). Harcourt Brace. 1985. p. 191. ISBN 0-03-054982-5.

- ^ For an overview of scholarship on the role of conversos in the development of the picaresque novel in 16th- and 17th-century Spain, see Halevi-Wise, Yael (2011). "The Life and Times of the Pícaro Converso from Spain to Latin America". In Halevi-Wise, Yael (ed.). Sephardism: Spanish Jewish History in the Modern Literary Imagination. Stanford University Press. pp. 143–167. ISBN 978-0-8047-7746-9.

- ^ Grimmelshausen, H. J. Chr. (1669). Der abentheurliche Simplicissimus [The adventurous Simplicissimus] (in German). Nuremberg: J. Fillion. OCLC 22567416.

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, Publishers. Springfield, Massachusetts, 1995. Page 3.

- ^ Paulson, Ronald (1965). "Reviewed Work: Rogue's Progress: Studies in the Picaresque Novel by Robert Alter". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 64 (2): 303. JSTOR 27714644.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael (2014). The Novel: A Biography. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

- ^ The title page of the first edition of Joseph Andrews lists its full title as: The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews, and of His Friend Mr. Abraham Adams. Written in Imitation of the Manner of Cervantes, Author of Don Quixote.

- ^ "Picaresque novel | literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- ^ a b "Picaresque", Britannica online.

- ^ Striedter, Jurij (1961). Der Schelmenroman in Russland: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Russischen Romans vor Gogol (in German). Berlin: Freien Universität. OCLC 1067476065.

- ^ Godsland, Shelley (2015), Garrido Ardila, J. A. (ed.), "The neopicaresque: The picaresque myth in the twentieth-century novel", The Picaresque Novel in Western Literature: From the Sixteenth Century to the Neopicaresque, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 247–268, ISBN 978-1-107-03165-4, retrieved 2021-03-11

- ^ Deters, Mary E. (1969). A Study of the Picaresque Novel in Twentieth-Century America (Master thesis). Wisconsin State University.

- ^ Chosen by Time magazine and Modern Library editors as one of the greatest English-language novels of the 20th century. See Under the Net.

- ^ As expressed by the author "With Baudolino, Eco Returns to Romance Writing". The Modern World. 11 September 2000. Archived from the original on 6 September 2006.

- ^ Sanderson, Mark (4 November 2003). "The picaresque, in detail". Telegraph. UK. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: NewThinkable (7 March 2013). "Class On Creative Reading – William S. Burroughs – 2/3". Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Fernández, Teodosio (2001). "Sobre la picaresca en Hispanoamérica". Edad de Oro (in Spanish). XX: 95–104. hdl:10486/670544. ISSN 0212-0429.

- ^ Weitzman, Erica (2006). "Imperium Stupidum: Švejk, Satire, Sabotage, Sabotage". Law and Literature. 18 (2). University of California Press: 117–148. doi:10.1525/lal.2006.18.2.117. ISSN 1535-685X. S2CID 144736158.

- ^ Thompson, William (2014). "The First & Second Books of Lankhmar". SF Site. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "1990: Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser". Totally Epic. Epic Comics. 27 May 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Review of "The First Book of Lankhmar" by Fritz Leiber". Speculiction. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "we ARE Rogue". The Outcast Rogue. Tumblr. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Roberto Chiti; Roberto Poppi; Enrico Lancia. Dizionario del cinema italiano. Gremese Editore, 1991.

- ^ Leonardo De Franceschi. Lo sguardo eclettico. Marsilio, 2001.

- ^ ""Wait! What? Aladdin is a Picaro?" by unknown". onthewarside.wordpress.com. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "False Profit". artforum. February 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

References

edit- Parker, Alexander Augustine (1967). Literature and the delinquent: the picaresque novel in Spain and Europe, 1599–1753. Norman Maccoll lecture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. OCLC 422136249.

- Cruz, Anne J. (2008). Approaches to teaching Lazarillo de Tormes and the picaresque tradition. Modern Language Association of America. ISBN 978-1-60329-016-6.

Further reading

edit- Robert Alter (1965), Rogue's progress: studies in the picaresque novel

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1979). "Does the Picaresque Novel Exist?". Kentucky Romance Quarterly. 16: 62–69. doi:10.1080/03648664.1979.9926339.

- Garrido Ardila, Juan Antonio, El género picaresco en la crítica literaria, Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 2008.

- Garrido Ardila, Juan Antonio, La novela picaresca en Europa, Madrid: Visor libros, 2009.

- Meyer-Minnemann, Klaus and Sabine Schlickers (eds), La novela picaresca: Concepto genérico y evolución del género (siglos XVI y XVII), Madrid, Iberoamericana, 2008.

- Klein, Norman M. and Margo Bistis, The Imaginary 20th Century, Karlsruhe, ZKM: Center for Art and Media, 2016. [1]

External links

editMedia related to Picaresque novel at Wikimedia Commons

- El Género Picaresco: La Novela Picaresca Española y Su Influencia (in Spanish)

- Fitzmaurice-Kelly, James (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). pp. 576–579.