Lieutenant General Count Pier Ruggero Piccio (27 September 1880 – 30 July 1965) was an Italian aviator and the founding Chief of Staff of the Italian Air Force. With 24 victories during his career, he is one of the principal Italian air aces of World War I, behind only Count Francesco Baracca and Tenente Silvio Scaroni. Piccio rose to the rank of Lieutenant General and in later years, became a Roman senator under the Fascists before and during World War II.

Lieutenant General Count Pier Ruggero Piccio | |

|---|---|

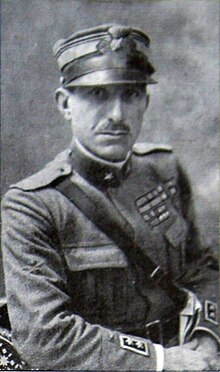

Pier Ruggero Piccio in L'Illustration. | |

| Born | 27 September 1880 Rome Lazio, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 30 July 1965 (aged 84) Rome, Lazio, Italy |

| Allegiance | Italy |

| Service | Artillery, infantry, aerial service |

| Years of service | 1900–1932 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Unit | 43rd Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Regiment, 19th Infantry Regiment, 5 Squadriglia, Squadriglia 3 |

| Commands | 77a Squadriglia, 10th Group Squadriglie, Regia Aeronautica |

| Battles / wars | World War I |

| Awards | Order of the Crown of Italy, Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, Medal for Military Valor (multiple awards), Military Order of Savoy, French Legion d'Honneur |

| Other work | Founded Regia Aeronautica. Senator and Minister in Mussolini's government. |

Early life

editPier Ruggero Piccio was born in Rome on 27 September 1880,[1] to Giacomo Piccio and Caterina Locatelli.[2] He attended the Military Academy of Modena, enrolling on October 29, 1898. He graduated on September 8, 1900, as a sottotenente (second lieutenant)[3] assigned to the 43rd Infantry Regiment.[1]

In 1903, stultified by garrison duty, he had himself seconded to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. At that time, Italy and Belgium had an agreement to allow for exchange duty between their militaries; Piccio's aim was service in the Belgian Congo.[3] From 5 November 1903 until 17 February 1907, he was engaged in a mission to Kalambari, Africa.[1] His return from Africa took him via Paris, where he managed to spend his three years' savings in a few days revelry. Upon his return to Italy, he shipped out again for foreign duty.[3] He spent from 13 March 1908 to 31 July 1909 assigned to the 2nd Mixed Company of Crete.[1]

From November 14, 1911, through December 2, 1912, he served in the Italo-Turkish War[1] (also sometimes called the Libyan War because Libya became an Italian protectorate as a result of the conflict). This war was notable for the first use of aircraft in battle, although the pioneer events of aerial reconnaissance and bombing occurred just before Piccio's arrival.[4] Piccio's duty station was with an artillery unit belonging to the 37th Infantry. During this service, while commanding a machine gun section, he was decorated with the Bronze Medal for Military Valor during February 1912.[1]

On 31 March 1913, Piccio was transferred to the 19th Infantry at the rank of captain. Then finally one of his attempts to attend aviation training succeeded; he was approved to attend the Malpensa flying school. On 27 July 1913, he qualified as a pilot upon Nieuport monoplanes.[3] After further training, he also qualified on 25 October to pilot Caproni bombers. He was then assigned to command 5a Squadriglia Aeroplani. On 31 December 1914, as Europe settled into the bitter trench warfare of World War I, Piccio was knighted in the Order of the Crown of Italy.[1]

World War I

editItaly organized its air assets into the Corpo Aeronautico Militare in January 1915. When Italy entered World War I in May 1915, Piccio went into combat. For his reconnaissance flights from May–August 1915, during which his craft was hit upon several occasions, he was again decorated with the Bronze Medal of Military Valor. In August, he was posted to Malpensa for additional training on Caproni bombers. After graduation, Piccio became commander of Squadriglia 3, which operated Capronis. Piccio commanded this squadron until February 1916.[1]

He spent March–April 1916 in Paris upgrading his Nieuport fighter skills. On 31 May 1916 he assumed command of the brand new 77a Squadriglia, a Nieuport fighter squadron stationed at Istrana, near Venice.[1] On 18 October 1916, he scored his first aerial victory, over an enemy observation balloon. The enterprising Piccio persuaded a nearby French escadrille into "loaning" him the latest in anti-balloon firepower, Le Prieur rockets–the loan being conditional upon French pilots partaking in the balloon busting expedition. Somehow, the flight line chauffeur was uncharacteristically late with the French pilots that day, and Piccio departed before their arrival. The subsequent victory won Piccio a silver medal for Military Valor for the hazardous combat duty of shooting a German observation balloon down in flames.[3]

On 26 January 1917, he was promoted to major.[1] On 15 April 1917, he was transferred to command the 10o Gruppo.[3] The group consisted of 91a Squadriglia, commanded by Francesco Baracca, in addition to the 77a Squadriglia. Piccio flew with either of the two squadrons within the group; though he spent the majority of his time with 77a, he tended to credit his victories to 91a, the "squadron of aces".[1]

On 20 May 1917, flying with the 91a Squadriglia, he shot down an Albatros to restart his victory tally. By June 29, he was an ace.[3] He continued to score, and on 2 August 1917, he caught Austro-Hungarian pilot Frank Linke-Crawford flying a two-seater without a rear gunner and shot him down for victory number eight. However, Linke-Crawford survived uninjured.[5]

Piccio accumulated successes until his double wins of October 25, 1917, at which time his tally was up to 17.[3] It was during this stretch of time he transferred from the Nieuport he had been flying, to a Spad adorned with a black flag painted on the fuselage.[citation needed] He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in October, 1917, being placed first in command of the "Fighter Mass", then as Inspector of Fighter Squadrons.[1] Once again, there was a break in his victory string.[3]

It wasn't until seven months later, on May 26, 1918, that he resumed his winning ways. He followed up with a victory in July, three in August, and an unconfirmed win on 29 September 1918.[3]

In the meantime, in the summer of 1918, he had become Inspector of Fighter Units. He seized the opportunity to reorganize the fighter squadrons. He instituted formation flying and patrol discipline; he codified the first Italian manual of air tactics. He was also decorated again, this time with the Gold Medal of Military Valor for his leadership skills,[3] as well as a Silver Medal of Military Valor.[citation needed]

Piccio had his fighter squadrons massed against the final Austro-Hungarian offensive in June 1918. They gained immediate air supremacy over the Luftfahrtruppen; the Austro-Hungarians called this dismal time the "Black Weeks" for good reason. They lost 22 percent of their pilots, 19 percent of their observers, and an appalling 41 percent of their aircraft between 15 and 24 June 1918. For all practical purposes, it was the effective end of the Austro-Hungarian air arm. The invaders' infantry now faced bombing and strafing from the air whenever there was flying weather.[6]

Piccio was shot down and captured on 27 October 1918.[citation needed] He was flying a ground attack mission into a storm of enemy ground fire, leading from the front as always, when he took a round in the engine and glided into captivity. He ended the war with 24 solidly confirmed victories.[3]

On November 4, the day of the Austro-Hungarian armistice, Piccio returned, having slipped out of the collapsing Empire in an enemy overcoat.[3]

Post War Life

editDomestic life

editIn 1918, even as the war ended, one rather dramatic report says Piccio was courting the young daughter of a deceased Louisiana millionaire. Piccio had been assigned to the Air Attaché's office of the Italian Embassy in Paris. Loranda Batchelder was just sixteen years old and finishing her education at École Lamartine. She supposedly fell for Piccio after he took her on a flight over Paris.[citation needed]

The teenager's mother objected to the match because of her daughter's age, but Piccio followed them to the United States and they were married in New York. They promptly returned to Paris, and from there, to Italy. They had one son, Pier Giacomo.[citation needed]

It was a stormy relationship that descended into a welter of cultural misunderstandings and child custody issues. While living in Italy, Loranda Piccio attempted to flee her husband during or before August 1924, taking her child with her, only to be thwarted.[citation needed] The marriage ended with the Countess's successful suit for annulment in July 1926.[7][8]

Piccio later married again, to Matilde Veglia.[2]

Professional life

editIn 1921, Piccio was named the Italian air attache in France.[3] In May 1922, the Italian military held joint force military maneuvers in Friuli; the air assets used had difficulty signaling military intelligence gained via reconnaissance to the exercise's ground forces because of deficiencies in communication equipment. The same weaknesses would be disclosed again during air/naval joint maneuvers in August 1923.[9]

Before the latter maneuvers, in January 1923, Piccio began service under Benito Mussolini. Mussolini was the titular head of the Italian commissariat of aviation; his aim was to establish a Fascist base in Italian military service. Aldo Finzi was installed as the civilian Undersecretary of the Air Force, with Piccio as his military deputy. Piccio had the skills needed to establish one of the original independent air forces (Britain being the other). At this time, France was the only other continental nation building their air power.[9]

The Italian Army and Navy air forces were merged into one in March 1923, forming the Regia Aeronautica. Finzi instituted new personnel and promotion policies for the new air force's officers, and Piccio carried them out. As pilots were being promoted over administrative officers in violation of existing regulations, dissatisfaction resulted. This situation only ended when Finzi left office in June 1924.[10] However, even as the Finzi/Piccio team purged the officers' ranks of deadwood, they succeeded in almost doubling the new air arm's 1923/1924 budget from 256 million lira to 450 million for the following year. They also began the practice of advertising for new aircraft designs. They established a corps of aeronautical engineers, as well as an air force academy, located in Livorno.[9]

Piccio was the senior officer serving as part of the establishment of the new air force;[9] thus, he was appointed the Commandant General of the Regia Aeronautica from October 23, 1923[3] through 17 April 1925. The job was then converted into Chief of Air Staff. Piccio returned to being the Air Attache in Paris, remaining in that post until 15 November 1925.[9]

Piccio held the post of Chief of Air Staff between 1 January 1926 and February 1927.[3] He was then appointed Chief of Air Staff in August, but didn't give up his Air Attache's job. He was constantly in conflict with the Undersecretary of State in the former role while doing neither job well. It did not end well. Piccio's superior, Italo Balbo, sacked Piccio for spending excessive time in Paris, where Piccio insisted he was still the Air Attaché. News of his playing the stock market and living luxuriously had led to cries of treason, which made Balbo's task easier.[11] Piccio was then promoted to air force Lieutenant General on 17 September 1932.[citation needed]

Piccio was named an honorary aide de camp of the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III as of 1 March 1923.[2]

He was appointed a Senator of the kingdom by his King on 11 March 1933,[3] as a member of the Fascist Party. Two years later, he was placed on permanent leave after 36 years military service.[citation needed] While in the Senate, he held several different positions. He spent two terms on the Board of Finance, from 1 May 1934 to 2 March 1939, and from 17 April 1939 to 28 January 1940. He served on the commission to verify new senators from 26 March 1939 through 5 August 1943. He was also on the foreign trade and customs legislation committee, from 17 April 1939 through 5 August 1943.[2]

None of this kept him from living mostly in France; in October 1934, he served as a backchannel between France's Premier Flandin and Foreign Secretary Laval and Piccio's own boss, Benito Mussolini.[12] Piccio even listed an address in Paris on his senatorial records.[2]

In 1940, while living in Geneva, Piccio met his former enemy and long-time friend, Belgian ace Willy Coppens. Coppens mentioned that they must be enemies again. Piccio showed him a cigarette case salvaged from the wreckage of an Austro-Hungarian plane, and remarked, "From 1915 to 1918 Italy was at war to eliminate the spiked helmets and now Mussolini has brought them back to us!" During World War II, Piccio continued to live in neutral Switzerland. He helped Italian soldiers who sought sanctuary after the mid-war armistice. He was also a liaison between the Italian and French resistance movements.[3]

Post World War II, he seems to have temporarily forfeited the wealth he had made as a fascist; there is a decree of forfeiture dated 29 November 1945. It is followed by a revocation on 30 June 1946.[2] Pier Piccio died in Rome, Italy on 31 July 1965.[3]

Decorations and Honours

edit- 1911/1912: Commemorative Medal of the Italo-Turkish war

- 1911/1912: Bronze Medaglia al Valore Militare (Medal for Military Valor)

- May to August 1915: Bronze Medaglia al Valore Militare

- 18 October 1916: Silver Medaglia al Valore Militare: First award

- 5 May 1918: Gold Medaglia al Valore Militare

- June 1918: Silver Medaglia al Valore Militare: Second award

- 17 May 1919: Officer of the Military Order of Savoy (A.D. - Aeronautical; Knight: 28 February 1918)

- 20 November 1924: Commander of the Order of the S.S. Maurice and Lazarus (Knight: 11 June 1922)

- 29 September 1935: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy (Grand Officer: 28 January 1926; Commander: 5 September 1923; Officer: 17 May 1919; Knight: 31 December 1914)

- Knight of the French Legion d'Honneur

- Silver military long-distance air navigation award, second degree[1][2]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Franks et al 1997, pp. 151-152.

- ^ a b c d e f g Italian senate's website page on Piccio [1] (In Italian, translated by Microsoft) Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Variale 2009, pp. 75-78.

- ^ Hallion 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Chant 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Varriale 2009, pp. 9-10.

- ^ "Milestones". Time Magazine. 12 July 1926. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2006.

- ^ "PICCIO MARRIAGE ANNULLED IN ITALY; Court Says Constraint Marked Agreement of War Ace and Loranda Batchelder. SHE FLED WITH BABY IN 1924 Taken Back From Mediterranean by Government Order, Count Then Being Head of Air Service. Marital Career Stormy. Flees Across Mediterranean". The New York Times. 27 December 1929. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Gooch 2005, pp. 55-57.

- ^ Wohl 2005, pp. 63, 66.

- ^ Gooch 2005, pp. 98, 108.

- ^ Gooch 2005, p. 260.

References

edit- Christopher Chant. Austro-Hungarian Aces of World War 1. Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1-84176-376-4, ISBN 978-1-84176-376-7.

- John Gooch (2007). Mussolini and His Generals: The Armed Forces and Fascist Foreign Policy, 1922-1940. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85602-7.

- Norman Franks (2000). Nieuport Aces of World War 1. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-961-1. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- Jon Guttman, Tony Holmes (2001). SPAD VII Aces of World War I. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-222-9. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- Hallion, Richard P. Strike From the Sky: The History of Battlefield Air Attack, 1910-1945. (second edition) University of Alabama Press, 2010. ISBN 0817356576, 9780817356576.

- Paolo Varriale (2009). Italian Aces of World War 1. Osprey Publishing Co, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84603-426-8.

- Robert Wohl. The Spectacle Of Flight: Aviation And The Western Imagination, 1920-1950 Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300106920, 9780300106923.