Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (French: Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers) is a science fiction adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne. It is often considered a classic within both its genres and world literature. The novel was originally serialised from March 1869 to June 1870 in Pierre-Jules Hetzel's French fortnightly periodical, the Magasin d'éducation et de récréation. A deluxe octavo edition, published by Hetzel in November 1871, included 111 illustrations by Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou.[2]

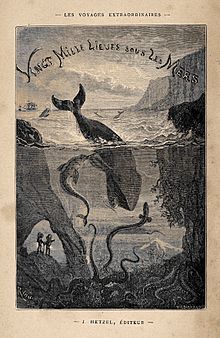

Frontispiece of 1871 edition | |

| Author | Jules Verne |

|---|---|

| Original title | Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers |

| Illustrator | Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou |

| Language | French |

| Series | Voyages extraordinaires Captain Nemo #1 |

| Genre | Adventure, Science fiction[1] |

| Publisher | Pierre-Jules Hetzel |

Publication date | March 1869 to June 1870 (as serial) 1870 (book form) |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1872 |

| Preceded by | In Search of the Castaways |

| Followed by | Around the Moon |

The book was widely acclaimed on its release, and remains so; it is regarded as one of the premier adventure novels and one of Verne's greatest works, along with Around the World in Eighty Days and Journey to the Center of the Earth. Its depiction of Captain Nemo's submarine, the Nautilus, is regarded as ahead of its time, since it accurately describes many features of modern submarines, which in the 1860s were comparatively primitive vessels.

Jules Verne saw a model of the French submarine Plongeur at the Exposition Universelle in 1867, which inspired him while writing the novel.[3][4][5]

Title

editThe title refers to the distance travelled under the various seas: 20,000 metric leagues (80,000 km, over 40,000 nautical miles), nearly twice the circumference of the Earth.[6]

Principal characters

edit- Professor Pierre Aronnax, a French natural scientist and the narrator of the story.

- Conseil, Aronnax's Flemish servant who is highly devoted to him and knowledgeable in biological classification.

- Ned Land, a Canadian harpooner, described as having "no equal in his dangerous trade".[7]

- Captain Nemo, the designer and captain of the Nautilus.

Plot

editIn 1866, ships of various nationalities sight a mysterious sea monster, which is speculated to be a gigantic narwhal. The U.S. government assembles an expedition in New York City to find and destroy the monster. Professor Pierre Aronnax, a French marine biologist and the story's narrator, is in town at the time and receives a last-minute invitation to join the expedition. Canadian whaler and master harpooner Ned Land and Aronnax's faithful manservant Conseil are also among the participants.

The expedition leaves Brooklyn aboard the United States Navy frigate Abraham Lincoln, then travels south around Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean. After a five-month search ending off Japan, the frigate locates and attacks the monster, which damages the ship's rudder. Aronnax and Land are hurled into the sea, and Conseil jumps into the water after them. They survive by climbing onto the "monster", which, they are startled to find, is a futuristic submarine. They wait on the deck of the vessel until morning, when they are captured and introduced to the submarine's mysterious constructor and commander, Captain Nemo.

The rest of the novel describes the protagonists' adventures aboard the Nautilus, which was built in secrecy and now roams the seas beyond the reach of land-based governments. In self-imposed exile, Captain Nemo seems to have a dual motivation — a quest for scientific knowledge and a desire to escape terrestrial civilization. Nemo explains that his submarine is electrically powered and can conduct advanced marine research; he also tells his new passengers that his secret existence means he cannot let them leave — they must remain on board permanently.

They visit many oceanic regions, some factual and others fictitious. The travelers view coral formations, sunken vessels from the Battle of Vigo Bay, the Antarctic ice barrier, the transatlantic telegraph cable, and the legendary underwater realm of Atlantis. They even travel to the South Pole and are trapped in an upheaval of an iceberg on the way back, caught in a narrow gallery of ice from which they are forced to dig themselves out. The passengers also put on diving suits, hunt sharks and other marine fauna with air guns in the underwater forests of Crespo Island, and attend an undersea funeral for a crew member who died during a mysterious collision experienced by the Nautilus. When the submarine returns to the Atlantic Ocean, a school of giant squid ("devilfish") attacks the vessel and kills another crewman.

The novel's later pages suggest that Captain Nemo went into undersea exile after his homeland was conquered and his family slaughtered by a powerful imperialist nation. Following the episode of the devilfish, Nemo largely avoids Aronnax, who begins to side with Ned Land. Ultimately, the Nautilus is attacked by a warship from the mysterious nation that has caused Nemo such suffering. Carrying out his quest for revenge, Nemo — whom Aronnax dubs an "archangel of hatred" — rams the ship below her waterline and sends her to the bottom, much to the professor's horror. Afterward, Nemo kneels before a portrait of his deceased wife and children, then sinks into a deep depression.

Circumstances aboard the submarine change drastically: watches are no longer kept, and the vessel wanders about aimlessly. Ned becomes so reclusive that Conseil fears for the harpooner's life. One morning, he announces that they are in sight of land and have a chance to escape. Professor Aronnax is more than ready to leave Captain Nemo, who now horrifies him, yet he is still drawn to the man. Fearing that Nemo's very presence could weaken his resolve, he avoids contact with the captain. Before their departure, the professor eavesdrops on Nemo and overhears him calling out in anguish, "O almighty God! Enough! Enough!". Aronnax immediately joins his companions as they carry out their escape plans, but as they board the submarine's skiff they realize that the Nautilus has seemingly blundered into the ocean's deadliest whirlpool, the Moskenstraumen (more commonly known as the "Maelstrom"). They escape and find refuge on an island off the coast of Norway. The submarine's ultimate fate remained unknown until the events of The Mysterious Island.

Themes and subtext

editCaptain Nemo's assumed name recalls Homer's Odyssey, when Odysseus encounters the monstrous Cyclops Polyphemus in the course of his wanderings. Polyphemus asks Odysseus his name, and Odysseus replies that it is Outis (Οὖτις) 'no one', translated into Latin as "Nemo". Like Captain Nemo, Odysseus wanders the seas in exile (though only for ten years) and similarly grieves the tragic deaths of his crewmen.

The novel repeatedly mentions the U.S. Naval Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury, an oceanographer who investigated the winds, seas, and currents, collected samples from the depths, and charted the world's oceans. Maury was internationally famous, and Verne may have known of his French ancestry.

The novel alludes to other Frenchmen, including Lapérouse, the celebrated explorer whose two sloops of war vanished during a voyage of global circumnavigation; Dumont d'Urville, a later explorer who found the remains of one of Lapérouse's ships; and Ferdinand de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal and nephew of the sole survivor of Lapérouse's ill-fated expedition. The Nautilus follows in the footsteps of these men: she visits the waters where Lapérouse's vessels disappeared; she enters Torres Strait and becomes stranded there, as did d'Urville's ship, the Astrolabe; and she passes beneath the Suez Canal via a fictitious underwater tunnel joining the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.

In possibly the novel's most famous episode, the above-described battle with a school of giant squid, one of the monsters captures a crew member. Reflecting on the battle in the next chapter, Aronnax writes: "To convey such sights, it would take the pen of our most renowned poet, Victor Hugo, author of The Toilers of the Sea." A bestselling novel in Verne's day, The Toilers of the Sea also features a threatening cephalopod: a laborer battles with an octopus, believed by critics to be symbolic of the Industrial Revolution. Certainly, Verne was influenced by Hugo's novel, and, in penning this variation on its octopus encounter, he may have intended the symbol to also take in the Revolutions of 1848.

Other symbols and themes pique modern critics. Margaret Drabble, for instance, argues that Verne's masterwork also anticipated the ecology movement and influenced French avant-garde imagery.[8] As for additional motifs in the novel, Captain Nemo repeatedly champions the world's persecuted and downtrodden. While in Mediterranean waters, the captain provides financial support to rebels resisting Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866–1869, proving to Professor Aronnax that he had not severed all relations with terrestrial mankind. In another episode, Nemo rescues an Indian pearl diver from a shark attack, then gives the fellow a pouch full of pearls, more than the man could have gathered after years of his hazardous work. When asked why he would help a "representative of that race from which he'd fled under the seas", Nemo responds that the diver, as an "East Indian", "lives in the land of the oppressed".[9]

Indeed, the novel has an under-the-counter political vision, hinted at in the character and background of Captain Nemo himself. In the book's final form, Nemo says to professor Aronnax, "That Indian, sir, is an inhabitant of an oppressed country; and I am still, and shall be, to my last breath, one of them!"[10] In the novel's initial drafts, the mysterious captain was a Polish nobleman, whose family and homeland were slaughtered by Russian forces during the Polish January Uprising of 1863. These specifics were suppressed during the editing stages at the insistence of Verne's publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel, believed responsible by today's scholars for many modifications of Verne's original manuscripts. At the time France was a putative ally of the Russian Empire, hence Hetzel demanded that Verne suppress the identity of Nemo's enemy, not only to avoid political complications but also to avert lower sales should the novel appear in Russian translation. Hence Professor Aronnax never discovers Nemo's origins.

Even so, a trace remains of the novel's initial concept, a detail that may have eluded Hetzel: its allusion to an unsuccessful rebellion under a Polish hero, Tadeusz Kościuszko, leader of the uprising against Russian and Prussian control in 1794;[11] Kościuszko mourned his country's prior defeat with the Latin exclamation "Finis Poloniae!" ("Poland is no more!").

Five years later, and again at Hetzel's insistence, Captain Nemo was revived and revamped for another Verne novel, The Mysterious Island. The novel changes the captain's nationality from Polish to Indian; in the book's final chapters, Nemo reveals that he is an Indian prince named Dakkar who was a descendant of Tipu Sultan, a prominent ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, and participated in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, an ultimately unsuccessful uprising against Company rule in India. After the rebellion, which led to the death of his family, Nemo fled beneath the seas, then made a final reappearance in the later novel's concluding pages.

Verne took the name "Nautilus" from one of the earliest successful submarines, built in 1800 by Robert Fulton, who also invented the first commercially successful steamboat. Fulton named his submarine after a marine mollusk, the chambered nautilus. As noted above, Verne also studied a model of the newly developed French Navy submarine Plongeur at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, which guided him in his development of the novel's Nautilus.[4]

The diving gear used by passengers on the Nautilus is presented as a combination of two existing systems: 1) the surface-supplied[12] hardhat suit, which was fed oxygen from the shore through tubes; 2) a later, self-contained apparatus designed by Benoit Rouquayrol and Auguste Denayrouze in 1865. Their invention featured tanks fastened to the back, which supplied air to a facial mask via the first-known demand regulator.[12][13][14] The diver didn't swim but walked upright across the seafloor. This device was called an aérophore (Greek for "air-carrier"). Its air tanks could hold only thirty atmospheres, but Nemo claims that his futuristic adaptation could do far better: "The Nautilus's pumps allow me to store air under considerable pressure ... my diving equipment can supply breathable air for nine or ten hours."

English translations

editThe novel was first translated into English in 1872 by Reverend Lewis Page Mercier. Mercier cut nearly a quarter of Verne's French text and committed hundreds of translating errors, sometimes drastically distorting Verne's original (including uniformly mistranslating the French scaphandre — properly "diving suit" — as "cork-jacket", following a long-obsolete usage as "a type of lifejacket"). Some of these distortions may have been perpetrated for political reasons, such as Mercier's omitting the portraits of freedom fighters on the wall of Nemo's stateroom, a collection originally including Daniel O'Connell[15] among other international figures. Mercier's text became the standard English translation, and some later retranslations continued to recycle its mistakes, including mistranslating the title as "... under the Sea", rather than "... under the Seas".

In 1962, Anthony Bonner published a translation of the novel with Bantam Classics. This edition included an introduction by Ray Bradbury, comparing Captain Nemo to Captain Ahab of Moby-Dick.[16]

A significant modern revision of Mercier's translation appeared in 1966, prepared by Walter James Miller and published by Washington Square Press.[17] Miller addressed many of Mercier's errors in the volume's preface and restored a number of his deletions in the text. In 1976, Miller published "The Annotated Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea"[18] at the suggestion of the Thomas Y. Crowel Company editorial staff.[19] The cover declared it "The only completely restored and annotated edition". In 1993, Miller collaborated with his fellow Vernian Frederick Paul Walter to produce "The Completely Restored and Annotated Edition", published in 1993 by the Naval Institute Press.[20] Its text took advantage of Walter's unpublished translation, which Project Gutenberg later made available online.

In 1998, William Butcher issued a new, annotated translation with the title Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas, published by Oxford University Press (ISBN 978-0-19-953927-7). Butcher includes detailed notes, a comprehensive bibliography, appendices and a wide-ranging introduction studying the novel from a literary perspective. In particular, his original research on the two manuscripts studies the radical changes to the plot and to the character of Nemo urged on Verne by Hetzel, his publisher.

In 2010, Frederick Paul Walter issued a fully revised, newly researched translation, 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas: A World Tour Underwater. Complete with an extensive introduction, textual notes, and bibliography, it appeared in an omnibus of five of Walter's Verne translations titled Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics and published by State University of New York Press (ISBN 978-1-4384-3238-0).

In 2017, David Coward issued a new translation published by Penguin Classics (ISBN 9780141394930) with the title Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, including a new introduction, notes, and a note on the text, using the 1871 Christian Chelebourg edition of the text as the basis for his translation. Coward also included 42 illustrations, which were published for the first time in the 'Collection Hetzel' in 1901.

Reception

editThe science fiction writer Theodore L. Thomas criticized the novel in 1961, claiming that "there is not a single bit of valid speculation" in the book and that "none of its predictions has come true". He described its depictions of Nemo's diving gear, underwater activities, and the Nautilus as "pretty bad, behind the times even for 1869 ... In none of these technical situations did Verne take advantage of knowledge readily available to him at the time." The notes to the 1993 translation point out that the errors Thomas notes were in Mercier's translation, not the original.

Despite his criticisms, Thomas conceded: "Put them all together with the magic of Verne's story-telling ability, and something flames up. A story emerges that sweeps incredulity before it".[13]

In 2023, Malaurie Guillaume presented Nemo as the first eco-terrorist or first figure of ecologic radicality.[21]

See also

edit- List of underwater science fiction works

- Adaptations of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas

- French corvette Alecton – Ship which encountered a giant squid

References

edit- ^ Canavan, Gerry (2018). The Cambridge History of Science Fiction. Cambridge University Press. (ISBN 978-1-31-669437-4)

- ^ Dehs, Volker; Jean-Michel Margot; Zvi Har'El, "The Complete Jules Verne Bibliography: I. Voyages Extraordinaires", Jules Verne Collection, Zvi Har’El, retrieved 2012-09-06

- ^ Payen, J. (1989). De l'anticipation à l'innovation. Jules Verne et le problème de la locomotion mécanique.

- ^ a b Notice at the Musée de la Marine, Rochefort

- ^ Compère, D. (2006). Jules Verne: bilan d'un anniversaire. Romantisme, (1), 87-97.

- ^ F. P. Walter's Project Gutenberg translation of Part 2, Chapter 7, reads: "Accordingly, our speed was 25 miles (that is, twelve four–kilometer leagues) per hour. Needless to say, Ned Land had to give up his escape plans, much to his distress. Swept along at the rate of twelve to thirteen meters per second, he could hardly make use of the skiff."

- ^ Verne, Jules (2010) [1870]. 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas. Translated by Frederick Paul Walter. ISBN 978-1-4384-3238-0 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Margaret Drabble (8 May 2014). "Submarine dreams: Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas". New Statesman. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- ^ Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics. State University of New York Press. February 2012. ISBN 9781438432403.

- ^ Verne, Jules. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea. New York, Charles Scribner's Sons. 1937, p. 221

- ^ He also travelled to the Thirteen Colonies and served as an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

- ^ a b Davis, RH (1955). Deep Diving and Submarine Operations (6th ed.). Tolworth, Surbiton, Surrey: Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd. p. 693.

- ^ a b Thomas, Theodore L. (December 1961). "The Watery Wonders of Captain Nemo". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 168–177.

- ^ Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "How Lewis Mercier and Eleanor King brought you Jules Verne". Ibiblio.org. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray. "The Pomegranate Architect". The Paris Review. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Jules Verne (author), Walter James Miller (trans.). Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Washington Square Press, 1966. Standard Book Number 671-46557-0; Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 65-25245.

- ^ Jules Verne; Walter James Miller (trans.) (1976). The Annotated Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. ISBN 0690011512.

- ^ Jules Verne; Walter James Miller (trans.) (1976). The Annotated Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. pp. Acknowledgements. ISBN 0690011512.

- ^ Jules Verne (author), Walter James Miller (trans.), Frederick Paul Walter (trans.). Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: A Completely Restored and Annotated Edition, Naval Institute Press, 1993. ISBN 978-1-55750-877-5.

- ^ Guillaume, Malaurie (2023-09-07). "Le capitaine Nemo était-il le premier éco-terroriste ?". Challenges. Archived from the original on 2023-10-10.

Le personnage de Jules Verne est sans doute la première figure de la radicalité écologique en prise avec les conséquences de la disparition du système terre. Car oui, le capitaine Nemo, c'est un leader écologiste radical qui dans les arcanes des abysses marins a inauguré une ZAD. Un protagoniste éclairant à l'heure où les efforts publics sont insuffisants face à la crise écologique, estime Guillaume Malaurie

External links

edit- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, trans. by F. P. Walter in 1991, made available by Project Gutenberg.

- Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea at Project Gutenberg, obsolete translation by Lewis Mercier, 1872

- Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers 1871 French edition at the digital library of the National Library of France

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, audio version (in French)

- Manuscripts of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea in gallica.bnf.fr Archived 2014-04-12 at the Wayback Machine