The pineal gland (also known as the pineal body[1] or epiphysis cerebri) is a small endocrine gland in the brain of most vertebrates. It produces melatonin, a serotonin-derived hormone, which modulates sleep patterns following the diurnal cycles.[2] The shape of the gland resembles a pine cone, which gives it its name.[3] The pineal gland is located in the epithalamus, near the center of the brain, between the two hemispheres, tucked in a groove where the two halves of the thalamus join.[4][5] It is one of the neuroendocrine secretory circumventricular organs in which capillaries are mostly permeable to solutes in the blood.[6]

| Pineal gland | |

|---|---|

Pineal gland or epiphysis (in red) | |

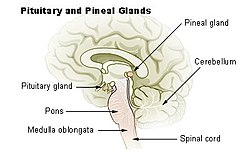

Diagram of pituitary and pineal glands in the human brain | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Neural ectoderm, roof of diencephalon |

| Artery | Posterior cerebral artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandula pinealis |

| MeSH | D010870 |

| NeuroNames | 297 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1184 |

| TA98 | A11.2.00.001 |

| TA2 | 3862 |

| FMA | 62033 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The pineal gland is present in almost all vertebrates, but is absent in protochordates in which there is a simple pineal homologue. The hagfish, considered as a primitive vertebrate, has a rudimentary structure regarded as the "pineal equivalent" in the dorsal diencephalon.[7] In some species of amphibians and reptiles, the gland is linked to a light-sensing organ, variously called the parietal eye, the pineal eye or the third eye.[8] Reconstruction of the biological evolution pattern suggests that the pineal gland was originally a kind of atrophied photoreceptor that developed into a neuroendocrine organ.

Ancient Greeks were the first to notice the pineal gland and believed it to be a valve, a guardian for the flow of pneuma. Galen in the 2nd century C.E. could not find any functional role and regarded the gland as a structural support for the brain tissue. He gave the name konario, meaning cone or pinecone, which during Renaissance was translated to Latin as pinealis. The 17th century philosopher René Descartes regarded the gland as having a mystical purpose, describing it as the "principal seat of the soul". In the mid-20th century, the biological role as a neuroendocrine organ was established.[9]

Etymology

editThe word pineal, from Latin pinea (pine-cone) in reference to the gland's similar shape, was first used in the late 17th century.[3]

Structure

editThe pineal gland is a pine cone-shaped (hence the name), unpaired midline brain structure.[3][10] It is reddish-gray in colour and about the size of a grain of rice (5–8 mm) in humans. It forms part of the epithalamus.[1] It is attached to the rest of the brain by a pineal stalk.[11] The ventral lamina of the pineal stalk is continuous with the posterior commissure, and its dorsal lamina with the habenular commissure.[11]

Location

editIt normally lies in a depression between the two superior colliculi.[11] It is situated between the laterally positioned thalamic bodies, and posterior to the habenular commissure. It is located in the quadrigeminal cistern.[1] It is located posterior to the third ventricle and encloses the small, cerebrospinal fluid-filled pineal recess of the third ventricle which projects into the stalk of the gland.[12]

Blood supply

editUnlike most of the mammalian brain, the pineal gland is not isolated from the body by the blood–brain barrier system;[13] it has profuse blood flow, second only to the kidney,[14] supplied from the choroidal branches of the posterior cerebral artery.

Afferents

editThe afferent nerve supply of pineal gland is by the nervus conarii which receives postganglionic sympathetic afferents from the superior cervical ganglion,[15] and parasympathetic afferents from the pterygopalatine ganglia and otic ganglia.[15][16] According to research on animals, neurons of the trigeminal ganglion that are involved in pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide neuropeptide signaling project the gland.[17][16]

Neural pathway for melatonin production

editThe canonical neural pathway regulating pineal melatonin production begins in the eye with the intrinsically photosensitive ganglion cells of the retina which project inhibitory GABAergic efferents to the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus via the retinohypothalamic tract. The paraventricular nucleus in turn projects to the superior cervical ganglia, which finally projects to the pineal gland. Darkness thus leads to disinhibition of the paraventricular nucleus, leading it to activate pineal gland melatonin production by way of the superior cervical ganglia.[18]

Microanatomy

editThe pineal body in humans consists of a lobular parenchyma of pinealocytes surrounded by connective tissue spaces. The gland's surface is covered by a pial capsule.

The pineal gland consists mainly of pinealocytes, but four other cell types have been identified. As it is quite cellular (in relation to the cortex and white matter), it may be mistaken for a neoplasm.[19]

| Cell type | Description |

|---|---|

| Pinealocytes | The pinealocytes consist of a cell body with 4–6 processes emerging. They produce and secrete melatonin. The pinealocytes can be stained by special silver impregnation methods. Their cytoplasm is lightly basophilic. With special stains, pinealocytes exhibit lengthy, branched cytoplasmic processes that extend to the connective septa and its blood vessels. |

| Interstitial cells | Interstitial cells are located between the pinealocytes. They have elongated nuclei and a cytoplasm that is stained darker than that of the pinealocytes. |

| Perivascular phagocyte | Many capillaries are present in the gland, and perivascular phagocytes are located close to these blood vessels. The perivascular phagocytes are antigen presenting cells. |

| Pineal neurons | In higher vertebrates neurons are usually located in the pineal gland. However, this is not the case in rodents. |

| Peptidergic neuron-like cells | In some species, neuronal-like peptidergic cells are present. These cells might have a paracrine regulatory function. |

Development

editThe human pineal gland grows in size until about 1–2 years of age, remaining stable thereafter,[20][21] although its weight increases gradually from puberty onwards.[22][23] The abundant melatonin levels in children are believed to inhibit sexual development, and pineal tumors have been linked with precocious puberty. When puberty arrives, melatonin production is reduced.[24]

Symmetry

editIn the zebrafish the pineal gland does not straddle the midline, but shows a left-sided bias. In humans, functional cerebral dominance is accompanied by subtle anatomical asymmetry.[25][26][27]

Function

editOne function of the pineal gland is to produce melatonin. Melatonin has various functions in the central nervous system, the most important of which is to help modulate sleep patterns. Melatonin production is stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light.[28][29] Light sensitive nerve cells in the retina detect light and send this signal to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), synchronizing the SCN to the day-night cycle. Nerve fibers then relay the daylight information from the SCN to the paraventricular nuclei (PVN), then to the spinal cord and via the sympathetic system to superior cervical ganglia (SCG), and from there into the pineal gland.

The compound pinoline is also claimed to be produced in the pineal gland; it is one of the beta-carbolines.[30] This claim is subject to some controversy.[citation needed]

Regulation of the pituitary gland

editStudies on rodents suggest that the pineal gland influences the pituitary gland's secretion of the sex hormones, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH). Pinealectomy performed on rodents produced no change in pituitary weight, but caused an increase in the concentration of FSH and LH within the gland.[31] Administration of melatonin did not return the concentrations of FSH to normal levels, suggesting that the pineal gland influences pituitary gland secretion of FSH and LH through an undescribed transmitting molecule.[31]

The pineal gland contains receptors for the regulatory neuropeptide, endothelin-1,[32] which, when injected in picomolar quantities into the lateral cerebral ventricle, causes a calcium-mediated increase in pineal glucose metabolism.[33]

Regulation of bone metabolism

editStudies in mice suggest that the pineal-derived melatonin regulates new bone deposition. Pineal-derived melatonin mediates its action on the bone cells through MT2 receptors. This pathway could be a potential new target for osteoporosis treatment as the study shows the curative effect of oral melatonin treatment in a postmenopausal osteoporosis mouse model.[34]

Clinical significance

editCalcification

editCalcification of the pineal gland is typical in young adults, and has been observed in children as young as two years of age.[35] The internal secretions of the pineal gland are known to inhibit the development of the reproductive glands because when it is severely damaged in children, development of the sexual organs and the skeleton are accelerated.[36] Pineal gland calcification is detrimental to its ability to synthesize melatonin[37][38] and scientific literature presents inconclusive findings on whether it causes sleep problems.[39][40]

The calcified gland is often seen in skull X-rays.[35] Calcification rates vary widely by country and correlate with an increase in age, with calcification occurring in an estimated 40% of Americans by age seventeen.[35] Calcification of the pineal gland is associated with corpora arenacea, also known as "brain sand".

Tumors

editTumors of the pineal gland are called pinealomas. These tumors are rare and 50% to 70% are germinomas that arise from sequestered embryonic germ cells. Histologically they are similar to testicular seminomas and ovarian dysgerminomas.[41]

A pineal tumor can compress the superior colliculi and pretectal area of the dorsal midbrain, producing Parinaud's syndrome. Pineal tumors also can cause compression of the cerebral aqueduct, resulting in a noncommunicating hydrocephalus. Other manifestations are the consequence of their pressure effects and consist of visual disturbances, headache, mental deterioration, and sometimes dementia-like behaviour.[42]

These neoplasms are divided into three categories: pineoblastomas, pineocytomas, and mixed tumors, based on their level of differentiation, which, in turn, correlates with their neoplastic aggressiveness.[43] The clinical course of patients with pineocytomas is prolonged, averaging up to several years.[44] The position of these tumors makes them difficult to remove surgically.

Other conditions

editThe morphology of the pineal gland differs markedly in different pathological conditions. For instance, it is known that its volume is reduced in both obese patients and those with primary insomnia.[45]

Other animals

editNearly all vertebrate species possess a pineal gland. The most important exception is a primitive vertebrate, the hagfish. Even in the hagfish, however, there may be a "pineal equivalent" structure in the dorsal diencephalon.[7] A few more complex vertebrates have lost pineal glands over the course of their evolution.[46] The lamprey (another primitive vertebrate), however, does possess one.[47] The lancelet Branchiostoma lanceolatum, an early chordate which is a close relative to vertebrates, also lacks a recognizable pineal gland.[47] Protochordates in general do not have the distinct structure as an organ, but they have a mass of photoreceptor cells called lamellar body, which is regarded as a pineal homologue.[48][49]

The results of various scientific research in evolutionary biology, comparative neuroanatomy and neurophysiology have explained the evolutionary history (phylogeny) of the pineal gland in different vertebrate species. From the point of view of biological evolution, the pineal gland is a kind of atrophied photoreceptor. In the epithalamus of some species of amphibians and reptiles, it is linked to a light-sensing organ, known as the parietal eye, which is also called the pineal eye or third eye.[8] It is likely that the common ancestor of all vertebrates had a pair of photosensory organs on the top of its head, similar to the arrangement in modern lampreys.[50] In many lower vertebrates (such as species of fish, amphibians and lizards), the pineal gland is associated with parietal or pineal eye. In these animals, the parietal eye acts as a photoreceptor, and hence are also known as the third eye, and they can be seen on top of the head in some species.[51] Some extinct Devonian fishes have two parietal foramina in their skulls,[52][53] suggesting an ancestral bilaterality of parietal eyes. The parietal eye and the pineal gland of living tetrapods are probably the descendants of the left and right parts of this organ, respectively.[54]

During embryonic development, the parietal eye and the pineal organ of modern lizards[55] and tuataras[56] form together from a pocket formed in the brain ectoderm. The loss of parietal eyes in many living tetrapods is supported by developmental formation of a paired structure that subsequently fuses into a single pineal gland in developing embryos of turtles, snakes, birds, and mammals.[57]

The pineal organs of mammals fall into one of three categories based on shape. Rodents have more structurally complex pineal glands than other mammals.[58]

Crocodilians and some tropical lineages of mammals (some xenarthrans (sloths), pangolins, sirenians (manatees and dugongs), and some marsupials (sugar gliders)) have lost both their parietal eye and their pineal organ.[59][60][58] Polar mammals, such as walruses and some seals, possess unusually large pineal glands.[59]

All amphibians have a pineal organ, but some frogs and toads also have what is called a "frontal organ", which is essentially a parietal eye.[61]

Pinealocytes in many non-mammalian vertebrates have a strong resemblance to the photoreceptor cells of the eye. Evidence from morphology and developmental biology suggests that pineal cells possess a common evolutionary ancestor with retinal cells.[62]

Pineal cytostructure seems to have evolutionary similarities to the retinal cells of the lateral eyes.[62] Modern birds and reptiles express the phototransducing pigment melanopsin in the pineal gland. Avian pineal glands are thought to act like the suprachiasmatic nucleus in mammals.[63] The structure of the pineal eye in modern lizards and tuatara is analogous to the cornea, lens, and retina of the lateral eyes of vertebrates.[57]

In most vertebrates, exposure to light sets off a chain reaction of enzymatic events within the pineal gland that regulates circadian rhythms.[64] In humans and other mammals, the light signals necessary to set circadian rhythms are sent from the eye through the retinohypothalamic system to the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) and the pineal gland.

The fossilized skulls of many extinct vertebrates have a pineal foramen (opening), which in some cases is larger than that of any living vertebrate.[65] Although fossils seldom preserve deep-brain soft anatomy, the brain of the Russian fossil bird Cerebavis cenomanica from Melovatka, about 90 million years old, shows a relatively large parietal eye and pineal gland.[66]

History

editThe secretory activity of the pineal gland is only partially understood. Its location deep in the brain suggested to philosophers throughout history that it possessed particular importance. This combination led to its being regarded as a "mystery" gland with mystical, metaphysical, and occult theories surrounding its perceived functions. The earliest recorded description of the pineal gland is from the Greek physician Galen in the 2nd century C.E.[67] According to Galen, Herophilus (325–280 B.C.E.) had already considered the structure as a kind of valve that partitioned the brain chambers, particularly for the flow of vital spirits (pneuma).[68] Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed that the structure maintained the movement of vital spirits from the middle (now identified as the third) ventricle to the one in the parencephalis (fourth ventricle).[69][70]

Galen described the pineal gland in De usu partium corporis humani, libri VII (On the Usefulness of Parts of the Body, Part 8) and De anatomicis administrationibus, libri IX (On Anatomical Procedures, Part 9).[71] He introduced the name κωνάριο (konario, often Latinised as conarium) that means cone, as in pinecone,[72] in De usu partium corporis humani. He correctly located the gland as directly lying behind the third ventricle. He argued against the prevailing concept of it as a valve for two basic reasons: it is located outside of the brain tissue and it does not move on its own.[67]

Galen instead identified the valve as a worm-like structure in the cerebellum (later called vermiform epiphysis, known today as the vermis cerebelli or cerebellar vermis).[73] From his study on the blood vessels surrounding the pineal gland he discovered the great vein of the cerebellum, later called the vein of Galen.[72][74] He could not establish any functional role of the pineal gland and regarded it as a structural support for the cerebral veins.[75]

Seventeenth-century philosopher and scientist René Descartes discussed the pineal gland both in his first book, the Treatise of Man (written before 1637, but only published posthumously 1662/1664), and in his last book, The Passions of the Soul (1649) and he regarded it as "the principal seat of the soul and the place in which all our thoughts are formed".[9] In the Treatise of Man, he described conceptual models of man, namely creatures created by God, which consist of two ingredients, a body and a soul.[9][76] In the Passions, he split man up into a body and a soul and emphasized that the soul is joined to the whole body by "a certain very small gland situated in the middle of the brain's substance and suspended above the passage through which the spirits in the brain's anterior cavities communicate with those in its posterior cavities". Descartes gave importance to the structure as it was the only unpaired component of the brain.[9]

The Latin name pinealis became popular in the 17th century. For example, English physician Thomas Willis described a glandula pinealis in his book, Cerebri anatome cui accessit nervorum descriptio et usus (1664). Willis criticised Descartes's concept, remarking: "we can scarce[ly] believe this to be the seat of the Soul, or its chief Faculties to arise from it; because Animals, which seem to be almost quite destitute of Imagination, Memory, and other superior Powers of the Soul, have this Glandula or Kernel large and fair enough."[75]

Walter Baldwin Spencer at the University of Oxford gave the first description of the pineal gland in lizards. In 1886, he described an eye-like structure, which he called the pineal eye or parietal eye, that was associated with the parietal foramen and the pineal stalk.[77] The presence of a pineal body was already discovered by German zoologist Franz Leydig in 1872, in European lizards. Leydig called them the "frontal organ" (German stirnorgan).[78][79] In 1918, Swedish zoologist Nils Holmgren described the "parietal eye" in frogs and dogfish.[80] He discovered that the parietal eyes were made up of sensory cells similar to the cone cells of the retina,[75] and suggested that it was a primitive light-sensor organ (photoreceptor).[80]

The pineal gland was originally believed to be a "vestigial remnant" of a larger organ. Epiphysan – an extract derived from the pineal glands of cattle – was historically used by veterinarians for rut suppression in mares and cows. In the 1930s it was tested on humans, and resulted in a temporary reduction in their masturbation impulse.[81] In 1917, it was known that extract of cow pineals lightened frog skin. Dermatology professor Aaron B. Lerner and colleagues at Yale University, hoping that a hormone from the pineal gland might be useful in treating skin diseases, isolated it and named it melatonin in 1958.[82] The substance did not prove to be helpful as intended, but its discovery helped solve several mysteries, such as why removing a rat's pineal gland accelerated its ovary growth, why keeping rats in constant light decreased the weight of their pineals, and why pinealectomy and constant light affect ovary growth to an equal extent; this knowledge gave a boost to the then-new field of chronobiology.[83] Of the endocrine organs, the function of the pineal gland was the last to be discovered.[84]

Society and culture

editThe notion of a "pineal-eye" is central to the philosophy of the French writer Georges Bataille, which is analyzed at length by literary scholar Denis Hollier in his study Against Architecture. In this work Hollier discusses how Bataille uses the concept of a "pineal-eye" as a reference to a blind-spot in Western rationality, and an organ of excess and delirium.[85] This conceptual device is explicit in his surrealist texts, The Jesuve and The Pineal Eye.[86]

In the late 19th century Madame Blavatsky, founder of theosophy, identified the pineal gland with the Hindu concept of the third eye, or the Ajna chakra. This association is still popular today.[9] The pineal gland has also featured in other religious contexts, such as in the Principia Discordia, which claims it can be used to contact the goddess of discord Eris.[87]

In the short story "From Beyond" by H. P. Lovecraft, a scientist creates an electronic device that emits a resonance wave, which stimulates an affected person's pineal gland, thereby allowing them to perceive planes of existence outside the scope of accepted reality, a translucent, alien environment that overlaps our own recognized reality. It was adapted as a film of the same name in 1986. The 2013 horror film Banshee Chapter is heavily influenced by this short story. In Season 16, episode 6 of "American Dad" Steve tries to "astral project" using his pineal gland to help him understand the meaning of life. The episode is entitled "The Wondercabinet".

Additional images

editThe pineal body is labeled in these images.

-

Mesal aspect of a brain sectioned in the median sagittal plane

-

Dissection showing the ventricles of the brain

-

Hind- and mid-brains; antero-lateral view

-

Median sagittal section of brain

-

Pineal gland

-

Brainstem; posterior view

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Chen CY, Chen FH, Lee CC, Lee KW, Hsiao HS (October 1998). "Sonographic characteristics of the cavum velum interpositum" (PDF). AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 19 (9): 1631–1635. PMC 8337493. PMID 9802483.

- ^ Reiter, R. J. (November 1991). "Neuroendocrine effects of light". International Journal of Biometeorology. 35 (3): 169–175. doi:10.1007/BF01049063. ISSN 0020-7128. PMID 1778647.

- ^ a b c "Pineal (as an adjective)". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Macchi MM, Bruce JN (2004). "Human pineal physiology and functional significance of melatonin". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 25 (3–4): 177–195. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.08.001. PMID 15589268. S2CID 26142713.

- ^ Arendt J, Skene DJ (February 2005). "Melatonin as a chronobiotic". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 9 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.05.002. PMID 15649736.

Exogenous melatonin has acute sleepiness-inducing and temperature-lowering effects during 'biological daytime', and when suitably timed (it is most effective around dusk and dawn) it will shift the phase of the human circadian clock (sleep, endogenous melatonin, cortisol) to earlier (advance phase shift) or later (delay phase shift) times.

- ^ Gross PM, Weindl A (December 1987). "Peering through the windows of the brain". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 7 (6): 663–672. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.1987.120. PMID 2891718. S2CID 18748366.

- ^ a b Ooka-Souda S, Kadota T, Kabasawa H (December 1993). "The preoptic nucleus: the probable location of the circadian pacemaker of the hagfish, Eptatretus burgeri". Neuroscience Letters. 164 (1–2): 33–36. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(93)90850-K. PMID 8152610. S2CID 40006945.

- ^ a b Eakin RM (1973). The Third Eye. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ a b c d e Lokhorst GJ (2018). Zalta EN (ed.). "Descartes and the Pineal Gland; In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy" (Winter 2018 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Bowen R. "The Pineal Gland and Melatonin". Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Waxman SG (2009). Clinical Neuroanatomy (26th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-07-160399-7.

- ^ Dorland's (2 May 2011). Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Elsevier Saunders. p. 1607. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Pritchard TC, Alloway KD (1999). Medical Neuroscience (Google books preview). Hayes Barton Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-889325-29-3. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ Arendt J: Melatonin and the Mammalian Pineal Gland, ed 1. London. Chapman & Hall, 1995, p 17

- ^ a b Møller M, Baeres FM (July 2002). "The anatomy and innervation of the mammalian pineal gland". Cell and Tissue Research. 309 (1): 139–150. doi:10.1007/s00441-002-0580-5. PMID 12111544. S2CID 25719864.

- ^ a b Møller M, Baeres FM (September 2003). "PACAP-containing intrapineal nerve fibers originate predominantly in the trigeminal ganglion: a combined retrograde tracing- and immunohistochemical study of the rat". Brain Research. 984 (1–2): 160–169. doi:10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03127-5. PMID 12932850. S2CID 40328108.

- ^ Liu W, Møller M (September 2000). "Innervation of the rat pineal gland by PACAP-immunoreactive nerve fibers originating in the trigeminal ganglion: a degeneration study". Cell and Tissue Research. 301 (3): 369–373. doi:10.1007/s004410000251. PMID 10994782. S2CID 5763932.

- ^ Tonon AC, Pilz LK, Markus RP, Hidalgo MP, Elisabetsky E (8 April 2021). "Melatonin and Depression: A Translational Perspective From Animal Models to Clinical Studies". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12: 638981. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638981. PMC 8060443. PMID 33897495.

- ^ Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Prayson RA (November 2006). "An algorithmic approach to the brain biopsy--part I". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 130 (11): 1630–1638. doi:10.5858/2006-130-1630-AAATTB. PMID 17076524.

- ^ Schmidt F, Penka B, Trauner M, Reinsperger L, Ranner G, Ebner F, Waldhauser F (April 1995). "Lack of pineal growth during childhood". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 80 (4): 1221–1225. doi:10.1210/jcem.80.4.7536203. PMID 7536203.

- ^ Sumida M, Barkovich AJ, Newton TH (February 1996). "Development of the pineal gland: measurement with MR". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 17 (2): 233–236. PMC 8338352. PMID 8938291.

- ^ Tapp E, Huxley M (September 1971). "The weight and degree of calcification of the pineal gland". The Journal of Pathology. 105 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1002/path.1711050105. PMID 4943068. S2CID 38346296.

- ^ Tapp E, Huxley M (October 1972). "The histological appearance of the human pineal gland from puberty to old age". The Journal of Pathology. 108 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1002/path.1711080207. PMID 4647506. S2CID 28529644.

- ^ "Melatonin Production and Age". Chronobiology. Medichron Publications.

- ^ Snelson CD, Santhakumar K, Halpern ME, Gamse JT (May 2008). "Tbx2b is required for the development of the parapineal organ". Development. 135 (9): 1693–1702. doi:10.1242/dev.016576. PMC 2810831. PMID 18385257.

- ^ Snelson CD, Burkart JT, Gamse JT (December 2008). "Formation of the asymmetric pineal complex in zebrafish requires two independently acting transcription factors". Developmental Dynamics. 237 (12): 3538–3544. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21607. PMC 2810829. PMID 18629869.

- ^ Snelson CD, Gamse JT (June 2009). "Building an asymmetric brain: development of the zebrafish epithalamus". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 20 (4): 491–497. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.11.008. PMC 2729063. PMID 19084075.

- ^ Axelrod J (September 1970). "The pineal gland". Endeavour. 29 (108): 144–148. PMID 4195878.

- ^ Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS (2000). "Genetics of the mammalian circadian system: Photic entrainment, circadian pacemaker mechanisms, and posttranslational regulation". Annual Review of Genetics. 34 (1): 533–562. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.533. PMID 11092838.

- ^ Callaway JC, Gyntber J, Poso A, Airaksinen MM, Vepsäläinen J (1994). "The pictet-spengler reaction and biogenic tryptamines: Formation of tetrahydro-β-carbolines at physiologicalpH". Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 31 (2): 431–435. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570310231.

- ^ a b Motta M, Fraschini F, Martini L (November 1967). "Endocrine effects of pineal gland and of melatonin". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 126 (2): 431–435. doi:10.3181/00379727-126-32468. PMID 6079917. S2CID 28964258.

- ^ Naidoo V, Naidoo S, Mahabeer R, Raidoo DM (May 2004). "Cellular distribution of the endothelin system in the human brain". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 27 (2): 87–98. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.12.002. PMID 15121213. S2CID 39053816.

- ^ Gross PM, Wainman DS, Chew BH, Espinosa FJ, Weaver DF (March 1993). "Calcium-mediated metabolic stimulation of neuroendocrine structures by intraventricular endothelin-1 in conscious rats". Brain Research. 606 (1): 135–142. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)91581-C. PMID 8461995. S2CID 12713010.

- ^ Sharan K, Lewis K, Furukawa T, Yadav VK (September 2017). "Regulation of bone mass through pineal-derived melatonin-MT2 receptor pathway". Journal of Pineal Research. 63 (2): e12423. doi:10.1111/jpi.12423. PMC 5575491. PMID 28512916.

- ^ a b c Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT (March 1982). "Age-related incidence of pineal calcification detected by computed tomography" (PDF). Radiology. 142 (3). Radiological Society of North America: 659–662. doi:10.1148/radiology.142.3.7063680. PMID 7063680. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "The Pineal Body". Human Anatomy (Gray's Anatomy). Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Kunz D, Schmitz S, Mahlberg R, Mohr A, Stöter C, Wolf KJ, Herrmann WM (December 1999). "A new concept for melatonin deficit: on pineal calcification and melatonin excretion". Neuropsychopharmacology. 21 (6): 765–772. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00069-X. PMID 10633482. S2CID 20184373.

- ^ Tan DX, Xu B, Zhou X, Reiter RJ (January 2018). "Pineal Calcification, Melatonin Production, Aging, Associated Health Consequences and Rejuvenation of the Pineal Gland". Molecules. 23 (2): 301. doi:10.3390/molecules23020301. PMC 6017004. PMID 29385085.

- ^ Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Lama J, Zambrano M, Castillo PR (November 2014). "Pineal gland calcification is not associated with sleep-related symptoms. A population-based study in community-dwelling elders living in Atahualpa (rural coastal Ecuador)". Sleep Medicine. 15 (11): 1426–1427. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.008. PMID 25277665.

- ^ Mahlberg R, Kienast T, Hädel S, Heidenreich JO, Schmitz S, Kunz D (April 2009). "Degree of pineal calcification (DOC) is associated with polysomnographic sleep measures in primary insomnia patients". Sleep Medicine. 10 (4): 439–445. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2008.05.003. PMID 18755628.

- ^ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC (5 September 2014). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1137. ISBN 9780323296359.

- ^ Bruce J. "Pineal Tumours". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Pineal Tumours". American Brain Tumour Association. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ Clark AJ, Sughrue ME, Ivan ME, Aranda D, Rutkowski MJ, Kane AJ, et al. (November 2010). "Factors influencing overall survival rates for patients with pineocytoma". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 100 (2): 255–260. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0189-6. PMC 2995321. PMID 20461445.

- ^ Tan DX, Xu B, Zhou X, Reiter RJ (January 2018). "Pineal Calcification, Melatonin Production, Aging, Associated Health Consequences and Rejuvenation of the Pineal Gland". Molecules. 23 (2): 301. doi:10.3390/molecules23020301. PMC 6017004. PMID 29385085. S2CID 25611663.

- ^ Erlich SS, Apuzzo ML (September 1985). "The pineal gland: anatomy, physiology, and clinical significance". Journal of Neurosurgery. 63 (3): 321–341. doi:10.3171/jns.1985.63.3.0321. PMID 2862230. S2CID 29929205.

- ^ a b Vernadakis AJ, Bemis WE, Bittman EL (April 1998). "Localization and partial characterization of melatonin receptors in amphioxus, hagfish, lamprey, and skate". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 110 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1006/gcen.1997.7042. PMID 9514841.

- ^ Lacalli TC (March 2008). "Basic features of the ancestral chordate brain: a protochordate perspective". Brain Research Bulletin. 75 (2–4): 319–323. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.038. PMID 18331892. S2CID 25837046.

- ^ Ivashkin E, Adameyko I (April 2013). "Progenitors of the protochordate ocellus as an evolutionary origin of the neural crest". EvoDevo. 4 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/2041-9139-4-12. PMC 3626940. PMID 23575111.

- ^ Cole WC, Youson JH (October 1982). "Morphology of the pineal complex of the anadromous sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus L". The American Journal of Anatomy. 165 (2): 131–163. doi:10.1002/aja.1001650205. PMID 7148728.

- ^ Dodt E (1973), Jung R (ed.), "The Parietal Eye (Pineal and Parietal Organs) of Lower Vertebrates", Visual Centers in the Brain, Handbook of Sensory Physiology, vol. 7 / 3 / 3 B, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 113–140, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-65495-4_4, ISBN 978-3-642-65497-8, retrieved 28 March 2023

- ^ Cope ED (1888). "The pineal eye in extinct vertebrates". American Naturalist. 22 (262): 914–917. doi:10.1086/274797. S2CID 85280810.

- ^ Schultze HP (1993). "Patterns of diversity in the skulls of jawed fishes". In Hanken J, Hall BK (eds.). The Skull. Vol. 2: Patterns of Structural and Systematic Diversity. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 189–254. ISBN 9780226315683. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Dodt E (1973). "The parietal eye (pineal and parietal organs) of lower vertebrates". Visual Centers in the Brain. Springer. pp. 113–140.

- ^ Tosini G (1997). "The pineal complex of reptiles: physiological and behavioral roles". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 9 (4): 313–333. doi:10.1080/08927014.1997.9522875.

- ^ Dendy A (1911). "On the structure, development and morphological interpretation of the pineal organs and adjacent parts of the brain in the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 201 (274–281): 227–331. doi:10.1098/rstb.1911.0006.

- ^ a b Quay WB (1979). "The parietal eye–pineal complex". In Gans C, Northcutt RG, Ulinski P (eds.). Biology of the Reptilia. Volume 9. Neurology A. London: Academic Press. pp. 245–406. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ^ a b Vollrath L (1979). Comparative Morphology of the Vertebrate Pineal Complex. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 52. pp. 25–38. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62909-X. ISBN 9780444801142. PMID 398532.

- ^ a b Ralph CL (December 1975). "The pineal gland and geographical distribution of animals". International Journal of Biometeorology. 19 (4): 289–303. Bibcode:1975IJBm...19..289R. doi:10.1007/bf01451040. PMID 1232070. S2CID 30406445.

- ^ Ralph C, Young S, Gettinger R, O'Shea TJ (1985). "Does the manatee have a pineal body?". Acta Zoologica. 66: 55–60. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.1985.tb00647.x.

- ^ Adler K (April 1976). "Extraocular photoreception in amphibians". Photophysiology. 23 (4): 275–298. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1976.tb07250.x. PMID 775500. S2CID 33692776.

- ^ Natesan A, Geetha L, Zatz M (July 2002). "Rhythm and soul in the avian pineal". Cell and Tissue Research. 309 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1007/s00441-002-0571-6. PMID 12111535. S2CID 26023207.

- ^ Moore RY, Heller A, Wurtman RJ, Axelrod J (January 1967). "Visual pathway mediating pineal response to environmental light". Science. 155 (3759): 220–223. Bibcode:1967Sci...155..220M. doi:10.1126/science.155.3759.220. PMID 6015532. S2CID 44377291.

- ^ Edinger T (1955). "The size of parietal foramen and organ in reptiles: a rectification". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 114: 1–34. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- ^ Kurochkin EN, Dyke GJ, Saveliev SV, Pervushov EM, Popov EV (June 2007). "A fossil brain from the Cretaceous of European Russia and avian sensory evolution". Biology Letters. 3 (3): 309–313. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0617. PMC 2390680. PMID 17426009.

- ^ a b Shoja MM, Hoepfner LD, Agutter PS, Singh R, Tubbs RS (April 2016). "History of the pineal gland". Child's Nervous System. 32 (4): 583–586. doi:10.1007/s00381-015-2636-3. PMID 25758643. S2CID 26207380.

- ^ Choudhry O, Gupta G, Prestigiacomo CJ (July 2011). "On the surgery of the seat of the soul: the pineal gland and the history of its surgical approaches". Neurosurgery Clinics of North America. 22 (3): 321–33, vii. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2011.04.001. PMID 21801980.

- ^ Berhouma M (September 2013). "Beyond the pineal gland assumption: a neuroanatomical appraisal of dualism in Descartes' philosophy". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 115 (9): 1661–1670. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.02.023. PMID 23562082. S2CID 9140909.

- ^ Cardinali DP (2016). "The Prescientific Stage of the Pineal Gland". Ma Vie en Noir. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 9–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41679-3_2. ISBN 978-3-319-41678-6.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Marín F, Álamo C (2016). "History of Pineal Gland as Neuroendocrine Organ and the Discovery of Melatonin". In López-Muñoz F, Srinivasan V, de Berardis D, Álamo C (eds.). Melatonin, Neuroprotective Agents and Antidepressant Therapy. New Delhi: Springer India. pp. 1–23. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2803-5_1. ISBN 978-81-322-2801-1. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ a b Laios K (July 2017). "The Pineal Gland and its earliest physiological description". Hormones. 16 (3): 328–330. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1751. PMID 29278521.

- ^ Steinsiepe KF (January 2023). "The 'worm' in our brain. An anatomical, historical, and philological study on the vermis cerebelli". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 32 (3): 265–300. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2022.2146515. PMID 36599122. S2CID 255470624.

- ^ Ustun C (September 2004). "Galen and his anatomic eponym: vein of Galen". Clinical Anatomy. 17 (6): 454–457. doi:10.1002/ca.20013. PMID 15300863.

- ^ a b c Pearce JM (2022). "The pineal: seat of the soul". Hektoen International. ISSN 2155-3017. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Descartes R (2002). "The Passions of the Soul". In Chalmers D (ed.). Philosophy of the Mind. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-514581-6.

- ^ Spencer B (1885). "On the Presence and Structure of the Pineal Eye in Lacertilia". Quarterly Journal of Microscopy. London: Bartholomew Close. pp. 1–76.

- ^ Flemming AF (1991). "A third eye". Culna (40): 26–27 – via Sabinet.

- ^ Eakin RM (1973). "3 Structure". The Third Eye. University of California Press. pp. 32–84. doi:10.1525/9780520326323-004. ISBN 978-0-520-32632-3.

- ^ a b Wurtman RJ, Axelrod J (July 1965). "The Pineal Gland". Scientific American. 213 (1): 50–60. Bibcode:1965SciAm.213a..50W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0765-50. PMID 14298722.

- ^ Talbot, Margaret (25 September 2023). "The Villa Where a Doctor Experimented on Children". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ Lerner AB, Case JD, Takahashi Y (July 1960). "Isolation of melatonin and 5-methoxyindole-3-acetic acid from bovine pineal glands". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 235 (7): 1992–1997. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)69351-2. PMID 14415935.

- ^ Coates PM, Blackman MR, Cragg GM, Levine M, Moss J, White JD (2005). Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. CRC Press. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-8247-5504-1. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ Sahai A, Sahai RJ (December 2013). "Pineal gland: A structural and functional enigma". Journal of the Anatomical Society of India. 62 (2): 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.jasi.2014.01.001.

- ^ Hollier D (1989). Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille. Translated by Wing B. MIT.

- ^ Bataille G (1985). Visions of excess: Selected writings 1927-1939. Manchester University Press.

- ^ "Principia Discordia - Page 15". principiadiscordia.com. Retrieved 22 September 2023.