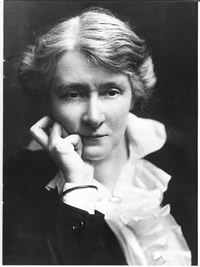

Edith Ailsa Geraldine Craig (née Edith Godwin; 9 December 1869 – 27 March 1947), known as Edy Craig, was a prolific theatre director, producer, costume designer and early pioneer of the women's suffrage movement in England. She was the daughter of actress Ellen Terry and the progressive English architect-designer Edward William Godwin, and the sister of theatre practitioner Edward Gordon Craig.

As a lesbian, an active campaigner for women's suffrage, and a woman working as a theatre director and producer, Edith Craig has been recovered by feminist scholars as well as theatre historians.[1] Craig lived in a ménage à trois with the dramatist Christabel Marshall and the artist Clare 'Tony' Atwood from 1916 until her death.[2][page needed][3][4][5]

Early years

editCraig, like her younger brother, Edward, was illegitimate, as her mother, Ellen Terry, was still married to her first husband George Frederic Watts when she eloped with Craig's father, Edward William Godwin, in 1868. Craig was born the following year at Gustardwood common in Hertfordshire.[6][7] Her birth name was Edith Godwin.[8] The family lived in Fallows Green, Harpenden in Hertfordshire, designed by Godwin, until 1874. The couple separated in 1875. In 1877 Terry married her second husband, Charles Wardell, an actor with the stage name Charles Kelly with whom she had worked. During the marriage, the children took the name Wardell, but after Terry and Wardell separated in 1881, Edith and her brother Edward changed their surname to Craig in 1883,[8] partly to avoid the stigma of their illegitimate birth.[9] She legally changed it in 1883 to Edith Ailsa Craig and was baptized Edith Ailsa Geraldine Craig in 1887.[citation needed]

Craig was educated at Mrs Cole's school, a co-educational institution in Earls Court in London, then studied at Dixton Manor, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, under Elizabeth Malleson, who introduced her to the suffrage movement, and later at the Royal Academy of Music.[8] Craig made her first appearance on the stage in 1878 during the run of Olivia at the Royal Court Theatre. She trained as a pianist under Alexis Hollander in Berlin, Germany, from 1887 to 1890.[10]

Theatre career

editCraig joined Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre company in 1890[8] as a costume designer and actress, touring America in 1895 and 1907 under the stage name Ailsa Craig. She was noted for historically accurate costumes and gained recognition for them. Like her younger brother, Craig appeared with Henry Irving in a number of plays, including The Bells (1895). In 1895 her performances in Pinero's Bygones and Charles Reade's The Lyons Mail respectively were praised by George Bernard Shaw and Eleonora Duse. George Bernard Shaw was a family friend of Craig's, he wrote several roles specifically for her. In Bernard Shaw's play Candida, it is believed that the role of Prossy was created for Craig, who originally played the role.[citation needed]

Craig also acted in plays by George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen, toured with Mrs Brown-Potter and the Independent Theatre.[10] During this time, she began to take over managing her mother’s career.[8] In 1899, Irving employed her to make the costumes for his production of Robespierre, which led to her going into business as a dressmaker as Edith Craig & Co in Covent Garden until 1903. After Ellen Terry left the Lyceum Theatre and went into management, Craig accompanied her on her tours in the English provinces and America as her stage-director, and from then play-production became her chief occupation.[10]

Craig founded the Pioneer Players (1911–1925), a theatre society based in London.[11][page needed] The Pioneer Players were known for producing formerly banned plays, plays on social humanism, women's suffrage and feminism and, from 1915, foreign plays in English. The plays in translation allowed the group to reach beyond the Actresses Franchise League and to be accepted into mainstream English theatre. Craig's mother, Ellen Terry, was president of the society. Craig served as the managing director / stage director, and her partner, Chris St. John, served as the secretary. An advisory committee included George Bernard Shaw and the President Gabrielle Enthoven.[12] The Pioneer Players has been described by some critics as a women's theatre company, increasing women's opportunities in theatre.[13] for whom Craig produced approximately 150 plays.[8]

After the Pioneer Players finally closed, Craig produced plays for the Little Theatre movement at York, Leeds, Letchworth and Hampstead. In 1919, she was an important figure in the British Drama League (BDL), which had been formed to promote amateur theatre throughout the United Kingdom, and to encourage a lasting peace after World War I.[14] Later Craig directed plays at the Everyman Theatre, Hampstead and Leeds Art Theatre.[15][page needed] In 1929, the year after Ellen Terry's death, Craig converted the Elizabethan barn adjacent to Terry's house at Smallhythe Place into a theatre which she named The Barn Theatre. Here she produced Shakespeare every year to commemorate the anniversary of her mother's death. Craig also appeared in a number of silent films,[16] including Fires of Fate (1923).

Craig was involved in many suffrage groups, and sold newspapers on behalf of that cause in the street. After she met a woman selling newspapers for the Women's Freedom she became a member and worked at branch level for that group. She did not fully understand the meaning of suffragism, but formed strong opinions about it quickly. She stated that she "grew up quite firmly certain that no self-respecting woman could be other than a suffragist". Craig used her theatrical experience on behalf of the Actresses' Franchise League and was also involved in various suffrage productions. She directed A Pageant of Great Women, a play she devised with the writer and actor Cicely Hamilton, which was performed across the United Kingdom before large audiences. A Pageant followed the concept of a morality play in which the main character, Woman, is confronted by the antagonist, Prejudice, who believes that men and women are not equal. Justice presides over the debate between Prejudice and Woman, as groups of great women process on stage as evidence of women's achievements in art, government, education, spiritual matters and battle.[17] Craig directed each production of this play, bringing the three professional actors to perform Woman, Justice and Prejudice and the historically accurate costumes with her to each venue. Craig frequently played the role of Rosa Bonheur, a lesbian artist.[10]

Personal life and death

editThe composer Martin Shaw proposed to Craig in 1903, and she accepted. However, the marriage was prevented by Ellen Terry, out of jealousy for her daughter's affection, and by Christabel Marshall, who wrote under the pseudonym Christopher St. John, with whom Craig lived from 1899 until they were joined in 1916 by the artist Clare 'Tony' Atwood, living in a ménage à trois until Craig's death in 1947.[2][3][4][5] Her lesbian lifestyle was looked down upon by her family. Her brother Edward said Edith's sexuality was a result of her "hatred of men, initiated by the hatred of her father". Craig became involved in several books about her mother and George Bernard Shaw which created a rift in the relationship with her brother, who asked Craig not to write about their mother, and specifically not to share the details of the family's innermost problems. Edward Gordon Craig's book Ellen Terry and her Secret Self (1931) explicitly objected to Ellen Terry and Bernard Shaw: a Correspondence (1931) edited by Christopher St. John. In 1932 Craig co-edited with St. John Ellen Terry's Memoirs in which she replied to her brother's representation of their mother. Also in 1932 Craig adopted Ruby Chelta Craig.[18] Craig was reconciled with her brother some time before her death.[10]

On the death of her mother Craig committed her life to preserving her mother's legacy. She opened the family home, Smallhythe Place in Kent, England to the public. From 1939 she was supported in running the house by the National Trust. On her death she left Smallhythe Place to the National Trust as a memorial to her mother.[19] Craig died of coronary thrombosis and chronic myocarditis on 27 March 1947 at Priest's House, Smallhythe Place while planning a Shakespeare festival in honour of her mother. Her body was cremated. Marshall and Atwood are buried alongside each other at St John the Baptist's Church, Small Hythe. Craig's ashes were supposed to be buried there as well, but at the time of Marshall and Atwood's deaths the ashes got lost, and a memorial was placed in the cemetery instead.[20]

Edith Craig suffered from acute arthritis especially in her hands. In her younger days, this painful condition prevented her from becoming a professional musician. She attended the Royal Academy of Music and held a certificate in piano from Trinity College. In her later years, after the death of her mother, Craig dictated her memoirs to her friend Vera Holme, known as Jacko. Holme wrote them down in a quarto notebook that was "lost in an attic" for decades and then sold to Ann Rachlin in 1978. They included Craig's reminiscences of her childhood and life with her mother, Edward Gordon Craig and Henry Irving. Rachlin published them in her book Edy was a Lady in 2011.[21]

Virginia Woolf is said to have used Edith Craig as a model for the character of Miss LaTrobe in her novel Between the Acts (1941).[14] A play by David Hare, to premiere in 2025 and starring Ralph Fiennes as Henry Irving, Grace Pervades, explores the life of Irving, Terry, Craig and her brother Edward.[22]

Selected filmography

edit- Her Greatest Performance (1916)

- God and the Man (1918)

- Victory and Peace (1918)

- The God in the Garden (1921)

- Fires of Fate (1923)

- The Desert Sheik (1924)

- Behind the Headlines (1937)

Sources

edit- Cockin, Katharine (1998). Edith Craig (1869–1947): Dramatic Lives. London: Cassell. ISBN 0304336459.

- Cockin, Katharine (2001). Women and Theatre in the Age of Suffrage: The Pioneer Players 1911–25, Palgrave.

- Cockin, Katharine (2005). "Cicely Hamilton's Warriors: Dramatic Reinventions of Militancy in the British Women's Suffrage Movement", Women's History Review, Vol. 14, No. 3 & 4.

- Gandolfi, Roberta (2003). La prima regista: Edith Craig, Roma: Bulzone Editore.

- Holroyd, Michael (2008). A Strange Eventful History: The Dramatic Lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving and Their Remarkable Families, London: Chatto & Windus.

- Rachlin, Ann (2011). Edy Was a Lady, Leicester: Matador.

Further reading

edit- Adlard, Eleanor, ed. (1949). Edy: Recollections of Edith Craig, London: Frederick Muller.

- Chiba, Yoko (1996). "Kori Torahiko and Edith Craig: A Japanese Playwright in London and Toronto", Comparative Drama, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 431–51.

- Cockin, Katharine (1991). "New Light on Edith Craig", Theatre Notebook, XLV, 3, pp. 132–43.

- Cockin, Katharine (1994). "The Pioneer Players: Plays of/with Identity", Difference in View: Women in Modernism, Gabriele Griffin (ed.) Taylor & Francis, pp. 142–54.

- Cockin, Katharine (2015). "Edith Craig and the Pioneer Players in a 'Khaki-clad and Khaki-minded World': London's International Art Theatre"], British Theatre and the Great War 1914–1919: New Perspectives, A. Maunder (ed.), Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 146–69.

- Dymkowski, Christine (1992). "Entertaining Ideas: Edy Craig and the Pioneer Players", The New Woman and Her Sisters, Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, pp. 221–33.

- Fisher, James (1995). "Edy Craig and the Pioneer Players' Production of Mrs Warren's Profession", Shaw, Vol. 15, pp. 37–56.

- Gandolfi, Roberta (2011). Ellen Terry, Spheres of Influence, Katharine Cockin (ed.), London: Pickering & Chatto, pp. 107–118.

- Holroyd, Michael (2008): A Strange Eventful History; The Dramatic Lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving and their Remarkable Families; Pub. Chatto & Windus ISBN 9780701179878

- Melville, Joy (1987). Ellen and Edy, London: Pandora.

- Steen, Marguerite (1962). A Pride of Terrys, London: Longmans.

- Webster, Margaret (1969). The Same Only Different, London: Victor Gollancz.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Dymkowski (1992); Cockin (1998); and Gandolfi (2003)

- ^ a b Holroyd (2008)

- ^ a b Rubin, Martin. "A Strange Eventful History: The Dramatic Lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving, and Their Remarkable Families by Michael Holroyd", Los Angeles Times, 23 March 2009, accessed 18 October 2015.

- ^ a b Rudd, Jill & Val Gough (eds.)Charlotte Perkins Gilmore: Optimist Reformer, University of Iowa Press, p. 90 (1999)

- ^ a b Law, Cheryl. Suffrage and Power: the Women's Movement, 1918–1928, i B Tauris & Co., p. 221 (1997)

- ^ Booth, Michael R. "Terry, Dame Ellen Alice (1847–1928)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004, online edn, January 2008, accessed 4 January 2010.

- ^ Profile of Terry by Amanda Hodges Archived 17 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f "Edith Craig", Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education (COVE), accessed January 22, 2022

- ^ Rachlin, p. 88

- ^ a b c d e Katharine Cockin, "Craig, Edith Ailsa Geraldine (1869–1947)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004, online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 10 March 2010

- ^ Cockin (2001)

- ^ Who's Who in the Theatre, 8th edition 1936, ed. John Parker

- ^ "The Orlando Project of Women Writers". Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ a b Cockin, Katharine. "Dame Ellen Terry and Edith Craig: Suitable Subjects for Teaching" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Wordplay, English Subject Centre Magazine, Issue 2, October 2009, accessed 18 October 2015

- ^ Cockin (1998)

- ^ Craig on the Internet Movie Database

- ^ Cockin (2005), pp. 527–42

- ^ Cockin (1998), p. 167

- ^ Ellen Terry and Edith Craig Database

- ^ Rachlin, Ann. Edy was a Lady. Troubador Publishing (2011), p. 62

- ^ Rachlin (2011), passim

- ^ "Ralph Fiennes / Theatre Royal Bath season announced for 2025 including new David Hare play Grace Pervades & As You Like It starring Gloria Obianyo & Harriet Walter", West End Theatre, 26 March 2024

External links

edit- Edith Craig at IMDb

- Craig on LGBT History Month Archived 31 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine