Dog fighting is a type of blood sport that turns game and fighting dogs against each other in a physical fight, often to the death, for the purposes of gambling or entertainment to the spectators.[1] In rural areas, fights are often staged in barns or outdoor pits; in urban areas, fights are often staged in garages, basements, warehouses, alleyways, abandoned buildings, neighborhood playgrounds, or in the streets.[2][3] Dog fights usually last until one dog is declared a winner, which occurs when one dog fails to scratch, dies, or jumps out of the pit.[4] Sometimes dog fights end without declaring a winner; for instance, the dog's owner may call the fight.[4]

Dog fighting generates revenue from stud fees, admission fees and gambling. Most countries have banned dog fighting, but it is still legal in some countries, such as Honduras,[citation needed] Japan,[6] and Albania.[7] The sport is also popular in Russia.[8][needs update]

History

editEurope

editBlood sports in general can be traced back to the Roman Empire.[9] In 13 BC, for instance, the ancient Roman circus slew 600 African beasts.[10] Dog fighting, more specifically, can also be traced to ancient Roman times. In AD 43, for example, dogs fought alongside the Romans and the British in the Roman Conquest of Britain.[9] In this war, the Romans used a breed that originated from Greece called the Molossus; the Britons used broad-mouthed Mastiffs, which were thought to descend from the Molossus bloodline and which also originated from Greece.[11] Though the British were outnumbered and ultimately lost this war, the Romans were so impressed with the English Mastiffs that they began to import these dogs for use in the Colosseum, as well as for use in times of war.[9] While spectators watched, the imported English Mastiffs were pitted against animals such as elephants, lions, bears and bulls, and also against gladiators.[9]

Later, the Romans bred and exported fighting dogs to Spain, France and other parts of Europe until eventually these dogs made their way back to England.[9] Though bull-baiting and bear-baiting were popular throughout the Middle Ages up to the 19th century in Germany, France, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands, the British pitted dogs against bulls and bears.[11] In 12th century England during the feudal era, the landed aristocracy, who held direct military control in decentralized feudal systems and thus owned the animals necessary for waging war, introduced bull baiting and bear baiting to the rest of the British population.[11] In later years, bull-baiting and bear-baiting became a popular source of entertainment for the British royalty.[11] For instance, Queen Elizabeth I, who reigned from 1558 to 1603, was an avid follower of bull- and bear-baiting; she bred Mastiffs for baiting and would entertain foreign guests with a fight whenever they visited England.[11] In addition to breeding Mastiffs and entertaining foreign guests with a fight, Queen Elizabeth, and later her successor, King James I, built a number of bear gardens in London.[12] The garden buildings were round and roofless, and housed not only bears, but also bulls and other wild animals that could be used in a fight.[12] Today, a person can visit the Bear Garden Museum near the Shakespeare Global Complex in Bankside, Southwark.[citation needed]

With the popularity of bull- and bear-baiting, bears needed for such fights soon became scarce.[11] With the scarcity of the bear population, the price of bears rose and, because of this, bull-baiting became more common in England over time.[11] Bulls who survived the fights were slaughtered afterwards for their meat, as it was believed that the fight caused bull meat to become more tender.[11] In fact, if a bull was offered for sale in the market without having been baited the previous day, butchers were liable to face substantial fines.[11] Animal fights were temporarily suspended in England when Oliver Cromwell seized power, but were reinstated again after the Restoration.[12] Dog fighting, bull-baiting, and bear-baiting were officially outlawed in England by the Humane Act of 1835.[13] The official ban on all fights, however, actually served to promote dog fighting in England.[12] Since a small amount of space was required for the pit where a dog fight took place, as compared to the ring needed for bull- or bear-baiting, authorities had a difficult time enforcing the ban on dog fighting.[12]

United States

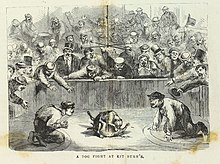

editIn 1817, the bull and terrier crossbreeds were brought to America and dog fighting slowly became part of American culture.[1] Yet, though historical accounts of dog fighting in America can be dated back to the 1750s, it was not until the end of the Civil War (1861–1865) that widespread interest and participation in the blood sport began in the United States.[3] For instance, in 1881, the Mississippi and Ohio railroads advertised special fares to a dog fight in Louisville; public forums such as Kit Burns' Tavern, "The Sportman's Hall", in Manhattan regularly hosted matches.[1] Many of these dogs thrown into the "professional pits" that flourished during the 1860s came from England and Ireland — where citizens had turned to dogs when bull-baiting and bear-baiting became illegal in their countries.[3]

In 20th century America, despite the expansion of laws to outlaw dog fighting, dog fighting continued to flourish underground.[3] Aiding in the expansion of dog fighting were the police and firemen, who saw dog fighting as a form of entertainment amongst their ranks.[3] In fact, the Police Gazette served as a go-to source for information about where one could attend a fight.[3] When Henry Bergh, who started the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), witnessed police involvement in these fights, he was motivated to seek and receive authority for the ASPCA Humane Law Enforcement Agents to have arresting power in New York.[3] Additionally, Bergh's 1867 revision to New York's animal cruelty law made all forms of animal fighting illegal.[3] However, According to the ASPCA website, the Humane Law Enforcement department of ASPCA has been disbanded and NYPD has taken over its duty.[3] As laws were passed to outlaw the activity, high-profile organizations, such as the United Kennel Club, who once endorsed the sport by formulating rules and sanctioning referees, withdrew their endorsement.[1]

On July 8, 2009, one of the largest dog fighting raids in U.S. history occurred. Law enforcement seized over 350 dogs, mostly pit bulls, and arrested 26 people across eight states. Most of the dogs were expected to have to be euthanized, as their harsh upbringing did not prepare them to be able to be safely placed in an adoptive home.[14][15]

Breed origins

editAccording to one scholar, Richard Strebel, the foundation for modern fighting dogs came from five dog types: the Tibetan Mastiff, the English Mastiff (out of which came the Dogue de Bordeaux, the Bulldog, and the Pug[citation needed]), the Great Dane (out of which came the Broholmer and the Boxer), the Newfoundland, and the Saint Bernard (out of which came the Leonberger).[12][16]: Table 1 However, Dieter Fleig disagreed with Strebel and offered the following list as composing the foundation of modern fighting dogs: the Tibetan Mastiff, the Molossus, the Bullenbeisser, the Great Dane, the English Mastiff, the Bulldog, the bull and terrier, and the Chincha Bulldog.[12][17][16]: Table 1 Other early dog types used for fighting included the Blue Paul Terrier,[18] the Córdoba Fighting Dog,[19] and the Dogo Cubano.[20]

The foundation breed of the fighting dog was, in its outward appearance, a large, low, heavy breed with a powerful build, strongly developed head, and tremendously threatening voice.[12] Additionally, these foundation breeds were also bred for a powerful jaw that would enable them to defend and protect humans, to overpower and pull down large animals on a hunt, and to control large, unmanageable domestic animals.[12] These dogs were also sometimes equipped with metal plates, chains, and collars with sharp spikes or hooked knives in order to be used in wars throughout history.[12]

When bull-baiting became popular in England due to the shortage of bears, bull-baiters soon realized that large fighting dogs were built too heavy and too slow for this type of combat.[11] When fighting a bull, dogs were trained to grab onto the bull's nose and pin the bull's head to the ground.[11] If the dog failed to do this, the bull would fling the dog out of the ring with its horns.[11] The British therefore decided to selectively breed fighting dogs for shorter legs and a more powerful jaw.[11] These efforts resulted in the Old English Bulldog.[11]

However, when countries started outlawing bull- and bear-baiting, dog fighters started pitting dogs against other dogs.[11] With the prevalence of such combat, dog fighters soon realized Bulldogs were inadequate and began to breed Bulldogs with terriers for more desired characteristics.[11] Terriers were most likely crossbred with Bulldogs due to their "generally rugged body structure", speed, aggression, and "highly developed gameness".[11] Yet, there is a debate over which type of terrier was bred with Bulldogs in order to create the bull and terrier. For instance, Joseph L. Colby claimed that it was the old English White Terrier that the bull and terrier is descended from, while Rhonda D. Evans and Craig J. Forsyth contend that its ancestor is the Rat Terrier.[11] Carl Semencic, on the other hand, held that a variety of terriers produced the bull and terrier.[11]

Eventually, out of crossbreeding Bulldogs and terriers, the English created the Staffordshire Bull Terrier.[3][21][22] When the Staffordshire Bull Terrier came to America in 1817, Americans began to selectively breed for gameness and created the American Pit Bull Terrier (originally known as the Pit Bull Terrier), which is a unique breed due to its absence of threat displays when fighting.[11][23][22][24] Bull Terriers,[25][22] Staffordshire Bull Terriers, American Pit Bull Terriers, and American Staffordshire Terriers,[26][22][24] are all breeds that are commonly labeled as "pit bulls".[27] The fact that pit bulls were historically bred to fight dogs, bulls, and bears has been used as one of the justifications in some US cities to implement breed-specific legislation.[28] Other breeds in which dogs at various stages of the breed history have sometimes been used as fighters include the Akita Inu,[29] the Boston terrier,[16]: Table 1 the Bully Kutta,[30] the Ca de Bou,[31] the Dogo Argentino,[32] the Gull Dong,[citation needed] the Gull Terrier,[citation needed] the Neapolitan Mastiff,[33] the Presa Canario,[34] the Spanish Mastiff,[35] and the Tosa.[36][37]

Societal aspects

editAfter interviewing 31 dogmen and attending 14 dog fights in the Southern United States, Evans, Gauthier, and Forsyth theorized on what attracts men to dog fights.[38] In their study, Evans, et al., discussed dog fighting's attractiveness in terms of masculinity and class immobility.[38] In the United States, masculinity embodies the qualities of strength, aggression, competition, and striving for success. By embodying these characteristics, a man can gain honor and status in his society.[38] Yet, working class occupations, unlike middle or upper class occupations, provide limited opportunities to validate this culturally accepted definition of masculinity.[38] So, working class men look for alternative ways to validate their masculinity and obtain honor and status. One way to do this is through dog fighting.[38] This is supported by the Evans, et al. findings: the majority of committed dogmen were mostly drawn from the working class, while the middle and upper classes were barely represented.[38] Men from middle and upper classes have opportunities to express their masculinity through their occupations; dog fighting, therefore, is just a hobby for them while it plays a central role in the lives of working class men.[38]

Aside from enjoyment of the sport and status, people are also drawn to dog fighting for money.[3] In fact, the average dog fight could easily net more money than an armed robbery or a series of isolated drug transactions.[39]

Bait animals

edit"Bait" animals are animals used to test a dog's fighting instinct; they are often mauled or killed in the process. Many of the training methods involve torturing and killing of other animals.[39] Often "bait" animals are stolen pets such as puppies, kittens, rabbits, small dogs and even stock (pit bulls acquired by the dog fighting ring which appear to be passive or less dominant).[40] Other sources for bait animals include wild or feral animals, animals obtained from a shelter or animals obtained from "free to good home" ads.[41] The snouts of bait animals are often wrapped with duct tape to prevent them from fighting back and they are used in training sessions to improve a dog's endurance, strength or fighting ability.[42] A bait animal's teeth may also be broken to prevent them from fighting back.[40] If the bait animals are still alive after the training sessions, they are usually given to the dogs as a reward and the dogs finish killing them.[39]

Types of dog fighters

editStreet fighters

editOften associated with gang activity, street fighters fight dogs over insults, turf invasions, or simple taunts like "my dog can kill your dog".[3] These type of fights are often spontaneous; unorganized; conducted for money, drugs, or bragging rights; and occur on street corners, back alleys, and neighborhood playgrounds.[3] Urban street fighters generally have several dogs chained in backyards, often behind privacy fences, or in basements or garages.[43] After a street fight, the dogs are often discovered by police and animal control officers either dead or dying.[3] Due to the spontaneity and secrecy of a street fight, they are very difficult to respond to unless reported immediately.[3]

Hobbyists and professionals often decry the techniques that street fighters use to train their dogs.[3] Such techniques include starving, drugging, and physically abusing the dog.[3]

Hobbyists

editHobbyists fight dogs for supplemental income and entertainment purposes.[3] They typically have one or more dogs participating in several organized fights and operate primarily within a specific geographic network.[3] Hobbyists are also acquainted with one another and tend to return to predetermined fight venues repeatedly.[43]

Professionals

editProfessional fighters breed generations of skilled "game dogs" and take great pride in their dogs' lineage.[43] These fighters make a tremendous amount of money charging stud fees to breed their champions, in addition to the fees and winnings they collect for fighting them.[43] They also tend to own a large number of dogs — sometimes 50 or more.[3] Professionals also use trade journals, such as Your Friend and Mine, Game Dog Times, The American Warrior, and The Pit Bull Chronicle, to discuss recent fights and to advertise the sale of training equipment and puppies. Some fighters operate on a national or even international level within highly secret networks.[43] When a dog is not successful in a fight, a professional may dispose of it using a variety of techniques such as drowning, strangulation, hanging, gun shot, electrocution or some other method.[3] Sometimes professionals and hobbyists dispose of dogs deemed aggressive to humans to street fighters.[3]

Gang and criminal activities

editDog fighting is a felony in all 50 states of the United States of America, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.[44] While dog fighting statutes exist independently of general anti-cruelty statutes and carry stiffer penalties than general state anti-cruelty statutes, a person can be charged under both or can be charged under one, but not the other — depending on the evidence.[44] In addition to felony charges for dog fighting, 48 states and the District of Columbia have provisions within their dog fighting statutes that explicitly prohibit attendance as a spectator at a dog fighting exhibition.[45] Since Montana and Hawaii do not have such provisions, a person can pay an entrance fee to watch a dog fight in either state and not be convicted under these statutes. Additionally, 46 states and the District of Columbia make possessing, owning or keeping a fighting dog a felony.[46]

While dog fighting was previously seen as isolated animal welfare issues — and therefore rarely enforced, the last decade has produced a growing body of legal and empirical evidence that has revealed a connection between dog fighting and other crimes within a community, such as organized crime, racketeering, drug distribution, and/or gangs.[47] Within the gang community, fighting dogs compete with firearms as the weapon of choice; indeed, their versatile utility arguably surpasses that of a loaded firearm in the criminal underground. Drug dealers distribute their illicit merchandise, wagers are made, weapons are concealed, and the dogs mutilate each other in a bloody frenzy as crowds cheer them on.[43] Violence often erupts among the usually armed gamblers when debts are to be collected and paid.[43] There is also a concern for children who are routinely exposed to dog fighting and are forced to accept the inherent violence as normal.[48] The routine exposure of the children to unfettered animal abuse and neglect is a major contributing factor in their later manifestation of social deviance.[48]

Animal welfare and rights

editAnimal advocates consider dog fighting to be one of the most serious forms of animal abuse, not only for the violence that the dogs endure during and after the fights, but because of the suffering they often endure in training, which ultimately can lead to death.[citation needed]

According to a filing in U.S. District Court in Richmond by federal investigators in Virginia, which was obtained under the Freedom of Information Act and published by The Baltimore Sun on July 6, 2007, a losing dog or one whose potential is considered unacceptable faces "being put to death by drowning, strangulation, hanging, gun shot, electrocution or some other method".[49] Some of the training of fighting dogs may entail the use of small animals (including kittens) as prey for the dogs.[citation needed]

Legal status

editDog fighting has been popular in many countries throughout history and continues to be practiced both legally and illegally around the world. In the 20th and 21st centuries, dog fighting has increasingly become an unlawful activity in most jurisdictions of the world, despite the fact that in cultural practice it may be common.[citation needed]

Dog fighting is illegal throughout the entire European Union and most of South America.[50] The American Pit Bull Terrier is by far the most common breed involved in the blood sport. The Dogo Cubano and Córdoba Fighting Dog were used for fighting a century ago, but both of these breeds have become extinct.[citation needed]

Afghanistan

editPreviously banned by the Taliban during their rule, dog fighting has made a resurgence throughout Afghanistan as a common winter weekend pastime, especially in Kabul, where the fights are public and often policed to maintain safety to the spectators. Dogs are not fought to the death, but to submission.[51][needs update?]

Albania

editDog fighting has been legal in Albania for over 25 years in professional fights.[7]

Argentina

editArticle 3.8 of Law 14.346 on the Ill-Treatment and Acts of Cruelty to Animals of 1954 explicitly prohibits 'carrying out public or private acts of animal fights, fights of bulls and heifers, or parodies [thereof], in which animals are killed, wounded or harassed.'[52]

Australia

editDog fighting and the possession of any fighting equipment designed for dog fighting is illegal in all Australian states and territories.[53] The illegal nature of dog fighting in Australia means that injured dogs rarely get veterinary treatment, placing the dog's health and welfare at even greater risk.[53] "Restricted Breed Dogs" cannot be imported into Australia. These include the Dogo Argentino, the Tosa, the Fila Brasileiro, the Perro de Presa Canario and the American Pit Bull Terrier. Of these, the American Pit Bull Terrier and the Perro de Presa Canario are the only breeds currently known to exist in Australia and there are strict regulations on keeping these breeds, including a prohibition on transferring ownership.[54]

Bolivia

editBolivia passed a law in 2003 or 2004 criminalising dog fighting.[55]

Brazil

editIn Brazil, Federal Decree 24.645 promulgated in 1934 by president Getúlio Vargas specifically prohibited 'to cause an animal to fight with another'.[56] Additionally, article 32 of the Federal Environmental Crimes Law (9.605 of 12 February 1998) prohibits abuse and cruelty against animals under the penalty of imprisonment from three months to one year, and a fine.[57][56]

Canada

editDog fighting has been illegal in Canada since 1892; however, the current law requires police to catch individuals during the unlawful act, which is often difficult.[58]

China

editDog fighting is allowed under Chinese law, although gambling remains illegal.[59]

Costa Rica

editIn Costa Rica, dog fights were illegal for decades as a misdemeanor; since 2014 and after a legal reform, they became a felony and are punished with up to three years of imprisonment.[60][61]

India

editDog fighting is prevalent in some parts of India, particularly in the state of Haryana.[62] The practice is illegal under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960.[63]

Japan

editAccording to historical documents, Hōjō Takatoki, the 14th shikken (shōgun's regent) of the Kamakura shogunate was known to be obsessed with dog fighting, to the point where he allowed his samurai to pay taxes with dogs. During this period, dog fighting was known as inuawase (犬合わせ).[citation needed]

Dog fighting was considered a way for the samurai to retain their aggressive edge during peaceful times. Several daimyōs (feudal lords), such as Chōsokabe Motochika and Yamauchi Yōdō, both from Tosa Province (present-day Kōchi Prefecture), were known to encourage dog fighting. Dog fighting was also popular in Akita Prefecture, which is the origin of the Akita breed.[citation needed]

Dog fighting evolved in Kōchi to a form that is called tōken (闘犬). Under modern rules, dogs fight in a fenced ring until one of the dogs barks, yelps, or loses the will to fight. Owners are allowed to admit defeat, and matches are stopped if a doctor judges that it is too dangerous. Draws usually occur when both dogs will not fight or both dogs fight until the time limit. There are various other rules, including one that specifies that a dog will lose if it attempts to copulate. Champion dogs are called yokozuna, as in sumo. Dog fighting is not banned at a nationwide level, but the prefectures of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Fukui, Ishikawa, Toyama and Hokkaidō all ban the practice.[64] Currently, most fighting dogs in Japan are of the Tosa breed, which is native to Kōchi.[citation needed]

The European Union

editDog fighting is illegal throughout the European Union.[50]

Bulgaria

editIn 2019, an investigation by Hidden-in-Sight for the League Against Cruel Sports and the BBC highlighted a global trade in fighting dogs centered in Bulgaria.[65] Subsequently, in April, a raid took place where 58 people were arrested at the site of two fighting pits.[66]

Greece

editIn October 2018, Vice.Gr released an exposé into dog fighting in Greece and the Balkans. This covered how dog fighting is linked to serious organised group in the country. The piece was advised by Hidden-in-Sight.[67]

Ireland

editDog fighting has been illegal in Ireland for over 150 years, although the sport is still popular in underground circles.[68]

Guatemala

editArticle 62 §h of decree no. 5-2017 – Animal Protection and Welfare Act of Guatemala, enacted in April 2017, explicitly prohibits the promotion of, participation in and organisation of shows that include fighting between dogs.[69]

Honduras

editDog fighting had previously been popular for decades amongst the poorest people of Honduras. The most common dog of choice for trainers was the American Pit Bull Terrier. Matches were held in the shanty towns of Tegucigalpa, with fights taking place in a simple sand pit surrounded by bleachers, often with only a few dozen spectators. Dog Fighting was more of a spectating pastime for those living in poverty than a form of gambling for locals. Dog Fighting On The Rise Among Poor Of Honduras | The Seattle Times

On November 12, 2015, the Honduran National Congress approved the Animal Welfare Act which banned the use and ownership of fighting dogs. Anyone found subjecting a dog to, assisting in the management or organization of any form of dog fight training, matches or breeding programs can be imprisoned for 3–6 years.Honduras Bans Use Of Animals In Circuses And Dog Fighting

Kuwait

editDog fighting became illegal in Kuwait as well as animal abuse as is stated "The law stipulates penalties of up to one year imprisonment and a fine of KD 1,000 for anyone who abuses, neglects or offers animals for sale ".[70]

Mexico

editDog fighting became illegal in Mexico on June 24, 2017.[71][72]

Morocco

editSome breeds of dog previously imported from France on the black market are now illegal. However, dogfighting as an activity has not been specifically banned.[73]

New Zealand

editIn accordance with the Animal Welfare Act 1999, dog fighting is illegal within New Zealand. Breeding, training or owning dogs for fighting is also illegal.[74]

Pakistan

editEven though it has recently been banned by law, it is still being practiced in rural Pakistan, especially in provinces such as Punjab, Azad Kashmir, Sindh and Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa. Now Karachi is the most popular city about pit bull fighting with the proper rules. There can be as much as millions of rupees at stake for the owners of winning dogs,[75] so different breeds have carefully been bred and selected specifically for the purpose, such as the Bully Kutta.[citation needed]

Panama

editLaw 308 on the Protection of Animals was approved by the National Assembly of Panama on 15 March 2012. Article 7 of the law states: 'Dog fights, animal races, bullfights – whether of the Spanish or Portuguese style – the breeding, entry, permanence and operation in the national territory of all kinds of circus or circus show that uses trained animals of any species, are prohibited.' Horse racing and cockfighting were exempt from the ban.[76]

Paraguay

editOrganising fights between all animals, both in public and private, is prohibited in Paraguay under Law No. 4840 on Animal Protection and Welfare, promulgated on 28 January 2013. Specifically:

- 'The use of animals in shows, fights, popular festivals and other activities that imply cruelty or mistreatment, that can cause death, suffering or make them the object of unnatural and unworthy treatments' is prohibited (Article 30).

- 'Training domestic animals to carry out provoked fights, with the goal of holding a public or private show' is considered an 'act of mistreatment'. (Article 31)

- 'The use of animals in shows, fights, popular festivals, and other activities that imply cruelty or mistreatment, which may cause death, suffering or make them subject to unnatural or humiliating treatment' is considered a 'very serious infraction' (Article 32), which are punishable by between 501 and 1500 minimum daily wages (jornales mínimos, Article 39), and the perpetrator may be barred from 'acquiring or possessing other animals for a period that may be up to 10 years' (Article 38).[77]

The Philippines

editDog fighting is illegal in the Philippines, with those involved being convicted under animal cruelty laws.[78]

Russia

editAlthough animal cruelty laws exist in Russia, dog fighting is widely practiced. Laws prohibiting dog fights have been passed in certain places like Moscow by order of that city's mayor. In much of Russia, dog fights are legally held, generally using Caucasian Shepherd Dogs, Georgian shepherds and Central Asian Shepherd Dogs. Temperament tests, which are a common and relatively mild form of dog fighting used for breeding purposes, are fairly commonplace. Most dog fights are traditional contests used to test the stamina and ability of working dogs used to protect livestock. Unlike fights with pit bulls and other fighting breeds, a veterinarian is always on hand, the contests are never to the death, and serious injuries are very rare. Most fights are over in minutes when it is clear which dog is superior. At the end of three rounds, the contest is declared a draw.[79]

South Africa

editDog fighting has been declared illegal in the Republic of South Africa. However, it is still very popular in the underground world, with dog fighting being a highly syndicated and organized crime. The NSPCA (National Council of SPCAs) is the largest animal welfare organization in Africa, and has been the organization that has conducted the most raids and busts, of which the most recent was in 2013, where 18 people were arrested, and 14 dogs were involved. Dog fighting is practiced throughout the country, in the townships area where gangs and drugs are mostly associated with dog fighting.[citation needed]

Dog fighting has been well documented in South Africa, particularly in the Western Cape region of Stellenbosch. The Stellenbosch Animal Welfare Society (AWS) frequently responds to complaints of nighttime dog fighting in the town of Cloetesville, in which hundreds of dogs fight. Young children may be used to transport fighting dogs to avoid the arrest of the owners.[80][81]

Tsakane dog fighting case

editIn November 2013, the NSPCA arrested 18 suspects who were caught in the act of illegal dog fighting in Tsakane in the East Rand. The suspects were arrested and charged for illegal dog fighting. Dog fighting is a criminal and prosecutable offence in South Africa. 14 pit bull-type dogs were confiscated from the property and were used for fighting purposes. Some of the dogs were badly injured as a result of the fighting and had to be humanely euthanised.[82] On 5 February 2018, a guilty verdict was handed down on 17 of the suspects by the presiding Magistrate in the Nigel Regional Court. 10 men were found guilty of being spectators at this dog fight and were sentenced to two years under strict house arrest (Benedict Ngcobo, Gift Nkabinde, Sabelo Mtshali, Thabiso Mahlangu, Bongani Skakane, Lehlohonolo Nomadola, Thulane Dhlosi, Mxolisi Khumalo, Nkosana Masilela, Sipho Masombuka). All the convicted men were found unfit to possess firearms and found unfit to own dogs and, if found to be in possession of a dog, would be liable to 12 months direct imprisonment. Further to the life-changing conditions of house arrest, the 10 spectators were also sentenced to 360 hours of community service and a total of R50 000 to be paid to the NSPCA. During the course of this trial, one of the accused chose to plead guilty and was sentenced to R20 000 or 20 months imprisonment, which was suspended for five years on the condition that he did not re-offend.[83]

South Korea

editDog fighting is illegal in South Korea.[50]

Taiwan

editAccording to Article 10 of the Taiwan Animal Protection Law, any "fights between animals or between animals and people through direct or indirect gambling, entertainment, operation, advertisement and other illegitimate purposes" is prohibited and carries a fine ranging from NT$50,000 to NT$250,000.[84]

United Arab Emirates

editDog fighting is illegal in the United Arab Emirates according to Federal Law No. 16 of 2007 on animal welfare and its amendments in Federal Law No. 18 of 2016. It is considered an 'act of animal cruelty' that is punishable by either imprisonment for a term not exceeding one year, or a fine of 200,000 United Arab Emirates dirham, or both.[85]

United Kingdom

editDog fighting remains illegal under U.K. law.[86] Despite periodic dog fight prosecutions, however, illegal canine pit battles continued after the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835 of England and Wales.[87] The Protection of Animals Act 1911 was specific in outlawing "the fighting or baiting of animals".[88]

Sporting journals of the 18th and 19th centuries depict the Black Country and London as the primary English dog fight centers of the period.[89]

On 13 February 2019, the BBC News released an exposé on global dog fighting with strong U.K. links. [90] The investigation started in June 2016, run by Hidden-in-Sight for the League Against Cruel Sports and latterly with the BBC. The exposé centred on a dog fighting group out of Bulgaria, who had been shipping fighting dogs around the world to over 20 countries. This exposé was the final piece of the Project BLOODLINE campaign that was set up to raise awareness of this cruel sport, the current weak sentencing options in the U.K. and show how animal crime links closely to existing policing priorities.

United States

editDog fighting is a felony in all 50 U.S. states, as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.[44] In most of the U.S., a spectator at a dog fight can be charged with a felony, while some areas only consider it a misdemeanor offense. In addition, the federal U.S. Animal Welfare Act makes it unlawful for any person to knowingly sell, buy, possess, train, transport, deliver, or receive any dog for purposes of having the dog participate in an animal fighting venture. The act also makes it unlawful for any person to knowingly use the mail service of the United States Postal Service or any instrumentality of interstate commerce for commercial speech for purposes of advertising a dog for use in an animal fighting venture, promoting or in any other manner furthering an animal fighting venture, except as performed outside the limits of the states of the U.S.[91]

In the second largest dog fighting raid in U.S. history in August 2013, the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama handed down the longest prison term ever handed down in a federal dog fighting case: eight years.[92]

According to a Michigan State University College of Law study published in 2005, in the U.S., dog fighting was once completely legal and was sanctioned and promoted during the Colonial period through the Victorian and well into the 20th century. In the second half of the 19th century, dog fighting started to be criminalized in the U.S.[citation needed]

There is a US$5,000 reward for reporting dog fighting to the Humane Society of the United States[93] From the HSUS: How to spot signs of dog fighting in your community: an inordinate number of pit bull-type dogs being kept in one location, especially multiple dogs who are chained and seem unsocialized; dogs with scars on their faces, front legs and stifle area (hind end and thighs); dog fighting training equipment, such as "breaking sticks" or "break sticks" used to pry apart the jaws of dogs locked in battle, which are a foot long, flat on one side and appear to be sharpened; tires or "spring poles" (usually a large spring with rope attached to either end) hanging from tree limbs; or unusual foot traffic coming and going from a location at odd hours.

CNN in 2007 estimated that in the U.S., more than 100,000 people are engaged in dog fighting on a non-professional basis and roughly 40,000 individuals are involved as professionals in the sport of dog fighting as a commercial activity. Top fights are said to have purses of $100,000 or more.[94]

Further reading

edit- Espejo, Esther (2023). "Case report: First criminal conviction of dog fighting in Brazil: an international network organization". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 10. doi:10.3389/fvets.2023.1327436. PMC 10800658. PMID 38260207.

- Loeb, Josh (2024). "UK dog fighting ring had cross-Channel reach". Veterinary Record. 194 (8): 292–293. doi:10.1002/vetr.4166. PMID 38639257.

- Pierpoint, Harriet (2018). "Dog fighting: a role for veterinary professionals in tackling a harmful and illegal practice". Veterinary Record. 183 (18): 563–566. doi:10.1136/vr.k4527. PMID 30413580.

See also

edit- Breed-specific legislation

- Cockfight

- Cricket fighting

- Cur – Dog-fighting term for a cowardly dog[95][96]

- Gameness – Dog-fighting term for the willingness to fight[97]

- Spider fighting

References

edit- ^ a b c d Gitson, Hannah (2005). "Quick Summary of Dog Fighting". Animal Legal and Historical Center. Michigan State University College of Law. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Gibson 2005, section 1C.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Boucher, B.G. (2011). Pitt Bulls: Villains or Victims? Underscoring Actual Causes of Societal Violence. Lana'i City, Hawaii: Puff & Co Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9826964-7-7.

- ^ a b Forsyth, Craig J; Evans, Rhonda D (1998). "Dogmen: The Rationalization of Deviance" (PDF). Society and Animals. 6 (3): 203 to 218. doi:10.1163/156853098x00159. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Sir Edwin Landseer". Philadelphia : Philadelphia Museum of Art. October 4, 1981 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gibson 2005, section 3.

- ^ a b "Peshkopi, qeni fitues quhet... Obama". Dita. Archived from the original on 2014-06-22. Retrieved 2019-04-17. (in Albanian)

- ^ "Dogfighting latest Hobby of 'New Russians'". Russia Today. Moscow, Russia. February 8, 1999.

- ^ a b c d e Villavicencio, Monica (2007-07-19). "A History of Dogfighting". NPR. Archived from the original on 2018-04-13. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ Favre, David (2011-05-16). Animal Law: Welfare, Interests, and Rights. Frederick, MD: Wolter Kluwer Law and Business. ISBN 978-1-4548-3398-7. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Massey, Wil (2012). Bloodsport and the Michael Vick Dogfighting Case: A Critical Cultural Analysis (M.A. thesis). East Tennessee University. Archived from the original on 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2019-09-17. (Unpublished Masters Thesis)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fleig, Dieter (1996). The History of Fighting Dogs. Neptune, NJ: TFH Publications.

- ^ Gibson 2005, section 2.

- ^ "Inside America's Biggest Dog-Fighting Bust". July 9, 2009.

- ^ "Historic Eight-State Dog Fighting Raid—July 2009". ASPCA. Archived from the original on 2015-10-22. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ^ a b c Hecht, Erin E.; Smaers, Jeroen B. (2019). "Significant Neuroanatomical Variation Among Domestic Dog Breeds" (PDF). The Journal of Neuroscience. 39 (39): 7748–7758. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0303-19.2019. PMC 6764193. PMID 31477568. S2CID 201804417.

- ^ Morris (2001), p. 346.

- ^ Morris (2001), p. 348.

- ^ Morris (2001), p. 352.

- ^ Morris (2001), p. 369.

- ^ Fogle (2009), p. 181.

- ^ a b c d Parker, Heidi G.; Dreger, Dayna L. (25 April 2017). "Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development". Cell Reports. 19 (4): 697–708. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.079. PMC 5492993. PMID 28445722.

- ^ Fogle (2009), p. 176.

- ^ a b Lockwood, Randall (2013). Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff (2nd ed.). Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Fogle (2009), p. 182.

- ^ Alderton (1987), pp. 32–33.

- ^ staff (2005). "Melvindale.Michigan BSL". Animal Legal and Historical Center at Michigan State University College of Law. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ staff (2005). "Breed Specific Legislation: Related Ordinances". Animal Legal and Historical Center at Michigan State University College of Law. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ Morris (2001), pp. 357–358.

- ^ Symonds, Tom (24 May 2016). "Street dog fighting crackdown urged". BBC. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ Morris (2001), p. 355.

- ^ Fogle (2009), p. 248.

- ^ Fogle (2009), p. 249.

- ^ Morris (2001), pp. 351–352.

- ^ Alderton (1987), p. 102.

- ^ Alderton (1987), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Matsuu, Aya; Kawabe, Akemi (2004). "Incidence of Canine Babesia gibsoni Infection and Subclinical Infection among Tosa dogs in Aomori Prefecture, Japan". Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 66 (8): 893–897. doi:10.1292/jvms.66.893. PMID 15353837. S2CID 26621025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Iliopoulou, Maria A.; Rosenbaum, Rene P. "Understanding Blood Sports". Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law. 9: 125–140.

- ^ a b c Gibson, Hannah. "Overview of Dog Fighting". Animal Legal and Historical Center. Michigan State University College of Law. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Michael Vick Sentencing Plea To Court Filed on Behalf of Pit Bull Victims, Dog Owners, ADOA, NAIS and Other Groups". Archived from the original on 2008-10-25.

- ^ "U.S. Dog-Fighting Rings Stealing Pets for "Bait"". News.nationalgeographic.com. 2010-10-28. Archived from the original on 2007-09-23. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- ^ "Congressional commentary to 7 U.S.C. §2156". Archived from the original on 2008-10-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gibson 2005, section 4.

- ^ a b c Gibson 2005, section 8A.

- ^ Gibson 2005, section 9B.

- ^ Gibson 2005, section 9C.

- ^ Gibson 2005, section 1.

- ^ a b Gibson 2005, section 5B.

- ^ "Doggy Dans The Online Dog Trainer Reviews". Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Linzey, Andrew; Linzey, Clair (2018). The Palgrave Handbook of Practical Animal Ethics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 155. ISBN 9781137366719. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Motlagh, Jason. "The Dog Fighters of Kabul". Time. Kabul. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ "Ley 14346 – Malos Tratos y Actos de Crueldad a los Animales" (PDF) (in Spanish). National University of the Littoral. 27 November 1954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Is dog fighting illegal in Australia?". RSPCA Australia Knowledgebase. n.d. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Things you should know about restricted breed dogs" (PDF). November 4, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Neil Trent, Stephanie Edwards, Jennifer Felt, and Kelly O’Meara (2005). "International Animal Law, with a Concentration on Latin America, Asia, and Africa". The Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lane Azevedo Clayton (2011). "Overview of Brazil's Legal Structure for Animal Issues". Animal Legal & Historical Center. Michigan State University College of Law. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Lei nº 9.605 de 12 de Fevereiro de 1998". www.planalto.gov.br (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Canadian Federal Legislation regarding animal welfare". Cfhs.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- ^ Moon, Louise (19 April 2018). "Police break up dog-fighting ring in China where dog fights are legal but gambling is not". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Diputados aprueban ley que castiga hasta con tres años de cárcel peleas de perros La Nación. In Spanish

- ^ Congreso de Costa Rica aprueba Legislación en contra de las peleas de perros Archived 2015-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Humane Society International. 2014. In Spanish

- ^ "युवक अपने पिटबुल डॉगी से करवाता है हमला:पूरा गांव परेशान; ग्रामीण बोले- स्ट्रीट डॉग्स से भी लड़वाता है, FIR दर्ज" [Youth makes his pitbull dog attack: entire village upset; "fights even with street dogs"say villagers, FIR registered]. Dainik Bhaskar (in Hindi).

- ^ "PETA India asks govt to crackdown on 'illegal dogfights'". The Times of India. 2022-09-13. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- ^ "闘犬、闘鶏、闘牛等取締条例とは – わかりやすく解説 Weblio辞書". www.weblio.jp. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011.

- ^ "Dog fighting in Bulgaria". BBC News. 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ^ "Незаконните боеве с кучета: Образувано е досъдебно производство срещу криминално проявен" (in Bulgarian). 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Θοδωρής Χονδρόγιαννος (5 October 2018). "Το Παράνομο Εκτροφείο Pit Bull στο Λαύριο, οι Κυνομαχίες στην Κατερίνη, η Ατιμωρησία". Vice News (in Greek). Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Hosford, Paul (19 July 2014). "ISPCA warns that casual dog fighting is on the rise". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Decreto Número 5-2017 – Ley de Protección y Bienestar Animal" (PDF). Diario de Centro América (in Spanish). 306 (87). Government of Guatemala: 5. 3 April 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Justice for animals". 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Dog fights as sport now illegal in Mexico". Mexico News Daily. 2017-06-24. Archived from the original on 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

The blood sport of dog fighting became illegal today in Mexico.

- ^ Pacelle, Wayne (2017-04-26). "Mexico adopts felony-level penalties for dogfighting". Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

[Mexico's] Senate has put the final stamp of approval on a comprehensive law that bans all dogfighting in the country and establishes tough penalties, including imprisonment and fines, for anyone involved in dogfighting activities like organizing fights, owning or trading a dog, and attending a fight as a spectator.

- ^ Senoussi, Zoubida (9 August 2018). "Moroccan Government Unveils Final List of Banned Dog Breeds". Morocco World News. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Animal Welfare Act 1999". www.legislation.govt.nz/. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Dog fighting in pakistan is alive and kicking". January 23, 2012. Archived from the original on April 23, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "Panamá prohíbe las corridas de toros" (in Spanish). Anima Naturalis. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "Ley Nº 4840 / de Proteccion y Bienestar Animal". Leyes Paraguayas (in Spanish). Biblioteca y Archivo del Congreso de la Nación. 30 January 2013. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Strother, Jason (13 February 2015). "South Korean Dog Fighting Ring Organizers Return From Philippines". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Chivers, C. J. (9 February 2007). "A Brutal Sport Is Having Its Day Again in Russia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- ^ "Dog fights are back in the news… again". Animal-info.co.za. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- ^ Murphy, Caryle. "Hundreds of animals savaged in night-time dog fighting in Cloetesville".[dead link]

- ^ "18 arrested for dog fighting". News24. Archived from the original on 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- ^ "Justice in Tsakane Dog Fighting Case – NSPCA Cares about all Animals". NSPCA Cares about all Animals. 2018-04-20. Archived from the original on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "Taiwan – Cruelty – Taiwan Animal Protection Law | Animal Legal & Historical Center". www.animallaw.info. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021.

- ^ Ashley Hammond (27 May 2019). "Dog fighting in UAE? Incident of abused Rottweiler pup prompts ministry to issue warning". Gulf News. Al Nisr Publishing. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Winter, Stuart (25 May 2018). "Dog News: Soaring numbers of dogs stolen and forced to FIGHT – make sure YOURS isn't next". Express.co.uk. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Glaze, Ben (10 March 2018). "Mutilated dogs found dead at side of road were 'victims of fighting ring'". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Protection of Animals Act 1911". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Holt, Richard (1990). Sport and the British: A Modern History. Clarendon Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780192852298. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Inside the illegal world of organised dogfighting". BBC News. 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ^ "The Animal Welfare Act". United States Code. 2008. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ "Strong Sentences Handed Down By Alabama Court in Historic Dog Fighting Case". American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. November 12, 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-11-16. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ "How To Spot Dog Fighting and Get $5000 For Reporting" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ "Dogfighting a booming business, experts say". CNN. 2007-07-19. Archived from the original on 2013-04-28. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Dogfighting Terminology". Veterinary Forensics: Animal Cruelty Investigations. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 5 April 2013. pp. 372–373. doi:10.1002/9781118704738.app31. ISBN 9781118704738.

- ^ "Dog Fighting in Britain: The Shocking Reality". www.k9magazine.com. 2012-06-28. Archived from the original on 2018-09-13. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Cumming, Geoff (23 June 2006). "The shadowy, paranoid world of dogfighting". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018 – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

Bibliography

edit- Alderton, David (1987). The dog: the most complete, illustrated, practical guide to dogs and their world. London: New Burlington Books. ISBN 0-948872-13-6.

- Fogle, Bruce (2009). The encyclopedia of the dog. New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-6004-8.

- Gibson, Hannah (2005). "Detailed Discussion of Dog Fighting". Animal Legal and Historical Center. United States: Michigan State University College of Law. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- Morris, Desmond (2001). Dogs: The Ultimate Dictionary of Over 1,000 Dog Breeds. North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square Publishing. ISBN 1-57076-219-8.

News articles

edit- Staff (30 November 2007). "Dog fighting in Acadiana: Video part 1". KLFY TV 10. Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Webster, Richard (26 November 2007). "Dog fighting remains big business in Louisiana". New Orleans City Business. Archived from the original on 2008-03-14. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- Burke, Bill (17 June 2007). "Once limited to the rural South, dogfighting sees a cultural shift". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- Staff (7 July 2012). "Detroit Rapper Young Calicoe Raided After Dog Fighting Video Goes Viral". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2012-07-11.