A plasma propulsion engine is a type of electric propulsion that generates thrust from a quasi-neutral plasma. This is in contrast with ion thruster engines, which generate thrust through extracting an ion current from the plasma source, which is then accelerated to high velocities using grids/anodes. These exist in many forms (see electric propulsion). However, in the scientific literature, the term "plasma thruster" sometimes encompasses thrusters usually designated as "ion engines".[1]

Plasma thrusters do not typically use high voltage grids or anodes/cathodes to accelerate the charged particles in the plasma, but rather use currents and potentials that are generated internally to accelerate the ions, resulting in a lower exhaust velocity given the lack of high accelerating voltages.

This type of thruster has a number of advantages. The lack of high voltage grids of anodes removes a possible limiting element as a result of grid ion erosion. The plasma exhaust is 'quasi-neutral', which means that positive ions and electrons exist in equal number, which allows simple ion-electron recombination in the exhaust to neutralize the exhaust plume, removing the need for an electron gun (hollow cathode). Such a thruster often generates the source plasma using radio frequency or microwave energy, using an external antenna. This fact, combined with the absence of hollow cathodes (which are sensitive to all but noble gases), allows the possibility of using this thruster on a variety of propellants, from argon to carbon dioxide air mixtures to astronaut urine.[2]

Plasma engines are well-suited for interplanetary missions due to their high specific impulse.[3]

Many space agencies developed plasma propulsion systems, including the European Space Agency, Iranian Space Agency and Australian National University, who co-developed a double layer thruster.[4][5]

History

editSome plasma engines have seen active flight time and use on missions. The first use of plasma engines was a Pulsed plasma thruster on the Soviet Zond 2 space probe which carried six PPTs that served as actuators of the attitude control system. The PPT propulsion system was tested for 70 minutes on the 14 December 1964 when the spacecraft was 4.2 million kilometers from Earth.[6]

In 2011, NASA partnered with Busek to launch the first hall effect thruster aboard the Tacsat-2 satellite. The thruster was the satellite's main propulsion system. The company launched another hall effect thruster that year.[7] In 2020, research on a plasma jet was published by Wuhan University.[8] The thrust estimates published in that work, however, were subsequently shown to be almost nine times theoretically possible levels even if 100% of the input microwave power were converted to thrust.[9]

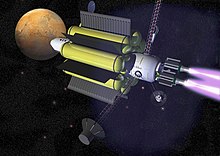

Ad Astra Rocket Company is developing the VASIMR. Canadian company Nautel is producing the 200 kW RF generators required to ionize the propellant. Some component tests and "Plasma Shoot" experiments are performed in a Liberia, Costa Rica laboratory. This project is led by former NASA astronaut Dr. Franklin Chang-Díaz (CRC-USA).

The Costa Rican Aerospace Alliance announced the development of exterior support for the VASIMR to be fitted outside the International Space Station. This phase of the plan to test the VASIMR in space was expected to be conducted in 2016.

Advantages

editPlasma engines have a much higher specific impulse (Isp) value than most other types of rocket technology. The VASIMR thruster can be throttled for an impulse greater than 12000 s, and hall thrusters have attained ~2000 s. This is a significant improvement over the bipropellant fuels of conventional chemical rockets, which feature specific impulses ~450 s.[10] With high impulse, plasma thrusters are capable of reaching relatively high speeds over extended periods of acceleration. Ex-astronaut Franklin Chang-Diaz claims the VASIMR thruster could send a payload to Mars in as little as 39 days[11] while reaching a maximum velocity of 34 miles per second (55 km/s).[citation needed]

Certain plasma thrusters, such as the mini-helicon, are hailed for their simplicity and efficiency. Their theory of operation is relatively simple and can use a variety of gases, or combinations.

These qualities suggest that plasma thrusters have value for many mission profiles.[12]

Drawbacks

editPossibly the most significant challenge to the viability of plasma thrusters is the energy requirement.[5] The VX-200 engine, for example, requires 200 kW electrical power to produce 5 N of thrust, or 40 kW/N. This power requirement may be met by fission reactors, but the reactor mass (including heat rejection systems) may prove prohibitive.[13][14]

Another challenge is plasma erosion. While in operation the plasma can thermally ablate the walls of the thruster cavity and support structure, which can eventually lead to system failure.[15]

Due to their extremely low thrust, plasma engines are not suitable for launch-to-Earth-orbit. On average, these rockets provide about 2 pounds of thrust maximum.[10] Plasma thrusters are highly efficient in open space, but do nothing to offset the orbit expense of chemical rockets.

Engine types

editHelicon plasma thrusters

editHelicon plasma thrusters use low-frequency electromagnetic waves (Helicon waves) that exist inside plasma when exposed to a static magnetic field. An RF antenna that wraps around a gas chamber creates waves and excites the gas, creating plasma. The plasma is expelled at high velocity to produce thrust via acceleration strategies that require various combinations of electric and magnetic fields of ideal topology. They belong to the category of electrodeless thrusters. These thrusters support multiple propellants, making them useful for longer missions. They can be made out of simple materials including a glass soda bottle.[12]

Magnetoplasmadynamic thrusters

editMagnetoplasmadynamic thrusters (MPD) use the Lorentz force (a force resulting from the interaction between a magnetic field and an electric current) to generate thrust. The electric charge flowing through the plasma in the presence of a magnetic field causes the plasma to accelerate. The Lorentz force is also crucial to the operation of most pulsed plasma thrusters.

Pulsed inductive thrusters

editPulsed inductive thrusters (PIT) also use the Lorentz force to generate thrust, but they do not use electrodes, solving the erosion problem. Ionization and electric currents in the plasma are induced by a rapidly varying magnetic field.

Electrodeless plasma thrusters

editElectrodeless plasma thrusters use the ponderomotive force which acts on any plasma or charged particle when under the influence of a strong electromagnetic energy density gradient to accelerate plasma electrons and ions in the same direction, thereby operating without a neutralizer.

VASIMR

editVASIMR, short for Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket, uses radio waves to ionize a propellant into a plasma. A magnetic field then accelerates the plasma out of the engine, generating thrust. A 200-megawatt VASIMR engine could reduce the time to travel from Earth to Jupiter or Saturn from six years to fourteen months, and from Earth to Mars from 6 months to 39 days.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mazouffre, Stéphane (2016-06-01). "Electric propulsion for satellites and spacecraft: established technologies and novel approaches" (PDF). Plasma Sources Science and Technology. 25 (3): 033002. Bibcode:2016PSST...25c3002M. doi:10.1088/0963-0252/25/3/033002. S2CID 41287361.

- ^ "Australian National University develops helicon plasma thruster". Dvice. January 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ "N.S. company helps build plasma rocket". cbcnews. January 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Plasma engine passes initial test". BBC News. 14 December 2005.

- ^ a b "Plasma jet engines that could take you from the ground to space". New Scientist. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ Shchepetilov, V. A. (December 2018). "Development of Electrojet Engines at the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy". Physics of Atomic Nuclei. 81 (7): 988–999. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ a b "TacSat-2". www.busek.com. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ "Could this Chinese plasma drive make green air travel a reality?". South China Morning Post. 8 May 2020.

- ^ Wright, Peter; Samples, Stephen; Uchizono, Nolan; Wirz, Richard (15 September 2020). "Comment on "Jet propulsion by microwave air plasma in the admosphere" [AIP Adv. 10, 05002 (2020)]". AIP Advances. 10 (9): 099101. Bibcode:2020AIPA...10i9101W. doi:10.1063/5.0013575. S2CID 224859826.

- ^ a b "Space Travel Aided by Plasma Thrusters: Past, Present and Future | DSIAC". www.dsiac.org. Archived from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ "Antimatter to ion drives: NASA's plans for deep space propulsion". Cosmos Magazine. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ a b "Rocket Aims For Cheaper Nudges In Space; Plasma Thruster Is Small, Runs On Inexpensive Gases". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ "Technical Information | Ad Astra Rocket". www.adastrarocket.com. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- ^ "The 123,000 MPH Plasma Engine That Could Finally Take Astronauts To Mars". Popular Science. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- ^ "Traveling to Mars with immortal plasma rockets". Retrieved 2017-07-29.