Townsend's big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) is a species of vesper bat.

| Townsend's big-eared bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Corynorhinus |

| Species: | C. townsendii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Corynorhinus townsendii Cooper, 1837

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

editTownsend's big-eared bat is a medium-sized bat (7-12 g)[2] with extremely long, flexible ears, and small yet noticeable lumps on each side of the snout. Its total length is around 10 cm (4 in.), its tail being around 5 cm (2 in) and its wingspan is about 28 cm (11 in).

The dental formula of Corynorhinus townsendii is 2.1.2.3.3.1.3.3. × 2 = 36[3]

Range

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2024) |

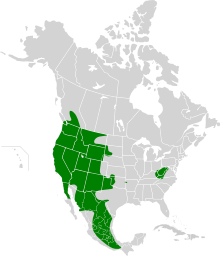

C. townsendii can be found in Canada, Mexico, and United States.[1]

Ecology

editThe mating season for the Townsend's big-eared bat takes place in late fall. As with many other bat species, the female stores sperm in her reproductive tract after mating, and fertilization occurs in the spring. Gestation lasts from 50 to 60 days. As with other bat species, pups are born without the ability to fly. Only one pup is birthed per female.[4] One study found the average lifespan of a Townsend's big-eared bat to be 16 years.[5]

This bat requires large cavities for roosting; these may include abandoned buildings and mines, caves, and basal cavities of trees.[2] During summer, these bats inhabit rocky crevices, caves, and derelict buildings. In winter, they hibernate in a variety of dwellings, including rocky crevices, caves, tunnels, mineshafts, spaces under loose tree bark, hollow trees, and buildings.[6] During the summer, males and females occupy separate roosting sites; males are typically solitary, while females form maternity colonies, where they raise their pups. A maternity colony may range in size from 12 bats to 200, although in the eastern United States, colonies of 1,000 or more have been formed.[2] During the winter, these bats hibernate, often when temperatures are around 32 to 53 °F (around 0 °C to 11.5 °C.) Townsend's roost singly during hibernation, forming small clusters only rarely. Males often hibernate in warmer places than females and are more easily aroused and active in winter than females. The bats are often interrupted from their sleep because they tend to wake up frequently and move around in the cave or move from one cave entirely to another. Before hibernation, C. townsendii individuals increase their body mass to compensate for the food they do not eat during the winter.[2]

This species has 2-3 feeding periods between dark and dawn, with periods of rest in between. They rest in areas different from where they roost during the day.[7]

During tests on straight-line courses, C. townsendii flew at speeds ranging from 2.9 to 5.5 m/s (6.4 to 12.3 mph).[8]

Diet and echolocation

editThis species is a moth specialist, and may feed almost exclusively on Lepidoptera.[9] However, its diet may include small moths, flies, lacewings, dung beetles, sawflies, and other small insects.[2] As a whisper bat, it echolocates at much lower intensities than other bats, and may be difficult to record using a bat detector. (This may be partly because it specializes on moths --- with some moths having the ability to hear bats, possibly producing their own noises to 'jam' a bat's echolocation in an effort to thwart predation.

Functional morphology

editC. townsendii, as well as its close relative C. rafinesquii, both have low wing loading, which means a large wing area to mass ratio. This morphology allows for a large amount of lift, high maneuverability, low-speed flight, and hovering during flight.[8]

Their large pinnae are usually in line with the body during flight; this indicates one of the roles of the pinnae is to impart lift during flight. The ears are also used to transmit sound into the bat's external auditory meatus, effectively distinguishing between ambient noise, and the sounds of predators or prey.[8]

Subspecies

editFive subspecies are described:[10]

- C. t. australis[10]

- C. t. townsendii – Townsend's big-eared bat

- C. t. ingens – Ozark big-eared bat (federally endangered)[11]

- C. t. pallescens – western big-eared bat

- C. t. virginianus – Virginia big-eared bat (federally endangered),[12] the Virginia state bat

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Álvarez-Castañeda, S.T. (2017). "Corynorhinus townsendii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T17598A21976681. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T17598A21976681.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Townsend's Big-eared Bat (Plecotus townsendii). Nsrl.ttu.edu. Retrieved on 2010-11-05.

- ^ Schwartz, Charles (2001). The Wild Mammals of Missouri. University of Missouri Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780826213594.

- ^ Townsend's Big-eared Bat – Colorado Division of Wildlife. Wildlife.state.co.us (2009-07-27). Retrieved on 2010-11-05. Archived October 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ministry of Environment – Okanagan Region – Townsend's Big-eared Bat. Env.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved on 2010-11-05.

- ^ Schwartz, Charles; Schwartz, Elizabeth (2001). The Wild Mammals of Missouri. Missouri: University of Missouri Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780826213594.

- ^ Schwartz, Charles; Schwartz, Elizabeth (2001). The Wild Mammals of Missouri. Missouri: University of Missouri Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780826213594.

- ^ a b c Kunz, Thomas; Martin, Robert (June 1982). "Plecotus townsendii". Mammalian Species (175): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503998. JSTOR 3503998.

- ^ Dobkin, David S. (1995), Radiotelemetry Study of Townsend's Big-eared Bat (Plecotus townsendii) on the Fort Rock Ranger District, Deschutes National Forest, Central Oregon, p. 35

- ^ a b "ITIS Standard Report Page: Corynorhinus townsendii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. United States Government. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Ozark Big-Eared Bats, Ozark Big-Eared Bat Pictures, Ozark Big-Eared Bat Facts – National Geographic. Animals.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved on 2010-11-05.

- ^ Virginia big-eared bat. Biology.eku.edu. Retrieved on 2010-11-05.

External links

edit- Media related to Corynorhinus townsendii at Wikimedia Commons

- Data related to Corynorhinus townsendii at Wikispecies