The brachial plexus is a network of nerves (nerve plexus) formed by the anterior rami of the lower four cervical nerves and first thoracic nerve (C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1). This plexus extends from the spinal cord, through the cervicoaxillary canal in the neck, over the first rib, and into the armpit, it supplies afferent and efferent nerve fibers to the chest, shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand.

| Brachial plexus | |

|---|---|

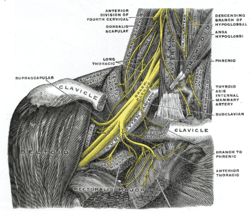

The right brachial plexus with its short branches, viewed from in front. | |

The roots, trunks and cords of the plexus shown in a dissected cadavaric specimen. | |

| Details | |

| Function | Network (nerve plexus) of nerves that supply the arms. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | plexus brachialis |

| MeSH | D001917 |

| TA98 | A14.2.03.001 |

| TA2 | 6395 |

| FMA | 5906 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Structure

editThe brachial plexus is divided into five roots, three trunks, six divisions (three anterior and three posterior), three cords, and five branches. There are five "terminal" branches and numerous other "pre-terminal" or "collateral" branches, such as the subscapular nerve, the thoracodorsal nerve, and the long thoracic nerve,[1] that leave the plexus at various points along its length.[2] A common structure used to identify part of the brachial plexus in cadaver dissections is the M or W shape made by the musculocutaneous nerve, lateral cord, median nerve, medial cord, and ulnar nerve.

Roots

editThe five roots are the five anterior primary rami of the spinal nerves, after they have given off their segmental supply to the muscles of the neck. The brachial plexus emerges at five different levels: C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1. C5 and C6 merge to establish the upper trunk, C7 continuously forms the middle trunk, and C8 and T1 merge to establish the lower trunk. Prefixed or postfixed formations in some cases involve C4 or T2, respectively. The dorsal scapular nerve comes from the superior trunk[2] and innervates the rhomboid muscles which retract and downwardly rotate the scapula. The subclavian nerve originates in both C5 and C6 and innervates the subclavius, a muscle that involves lifting the first ribs during respiration. The long thoracic nerve arises from C5, C6, and C7. This nerve innervates the serratus anterior, which draws the scapula laterally and is the prime mover in all forward-reaching and pushing actions.

Trunks

editThese roots merge to form the trunks:

Divisions

editEach trunk then splits in two, to form six divisions:

- anterior divisions of the upper, middle, and lower trunks

- posterior divisions of the upper, middle, and lower trunks

- when observing the body in the anatomical position, the anterior divisions are superficial to the posterior divisions

Cords

editThese six divisions regroup to become the three cords or large fiber bundles. The cords are named by their position with respect to the axillary artery.

- The posterior cord is formed from the three posterior divisions of the trunks (C5-C8, T1)

- The lateral cord is formed from the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks (C5-C7)

- The medial cord is simply a continuation of the anterior division of the lower trunk (C8, T1)

Diagram

edit

Branches

editThe branches are listed below. Most branches arise from the cords, but few branches arise (indicated in italics) directly from earlier structures. The five on the left are considered "terminal branches". These terminal branches are the musculocutaneous nerve, the axillary nerve, the radial nerve, the median nerve, and the ulnar nerve. Due to both emerging from the lateral cord the musculocutaneous nerve and the median nerve are well connected. The musculocutaneous nerve has even been shown to send a branch to the median nerve further connecting them.[1] There have been several variations reported in the branching pattern but these are very rare.[3]

Bold indicates primary spinal root component of nerve. Italics indicate spinal roots that frequently, but not always, contribute to the nerve.

| From | Nerve | Roots[4] | Muscles | Cutaneous |

| roots | dorsal scapular nerve | C4, C5 | rhomboid muscles and levator scapulae | - |

| roots | long thoracic nerve | C5, C6, C7 | serratus anterior | - |

| roots | branch to phrenic nerve | C3, C4,C5 | Diaphragm | - |

| upper trunk | nerve to the subclavius | C5, C6 | subclavius muscle | - |

| upper trunk | suprascapular nerve | C5, C6 | supraspinatus and infraspinatus | - |

| lateral cord | lateral pectoral nerve | C5, C6, C7 | pectoralis major and pectoralis minor (by communicating with the medial pectoral nerve) | - |

| lateral cord | musculocutaneous nerve | C5, C6, C7 | coracobrachialis, brachialis and biceps brachii | Becomes the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm Innervates the skin of the anterolateral forearm; elbow joint.[2] |

| lateral cord | lateral root of the median nerve | C5,C6,C7 | fibres to the median nerve

(see below) |

- |

| posterior cord | upper subscapular nerve | C5, C6 | subscapularis (upper part) | - |

| posterior cord | thoracodorsal nerve (middle subscapular nerve) | C6, C7, C8 | latissimus dorsi | - |

| posterior cord | lower subscapular nerve | C5, C6 | subscapularis (lower part ) and teres major | - |

| posterior cord | axillary nerve | C5, C6 | anterior branch: deltoid and a small area of overlying skin posterior branch: teres minor and deltoid muscles |

posterior branch becomes superior lateral cutaneous nerve of arm Innervates the skin of the lateral shoulder and arm: shoulder joint.[2] |

| posterior cord | radial nerve | C5, C6, C7, C8, T1 | triceps brachii, supinator, anconeus, the extensor muscles of the forearm, and brachioradialis | skin of the posterior arm and posterior forearm as the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm and the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm, respectively. Also superficial branch of radial nerve supplies back of the hand, including the web of skin between the thumb and index finger. |

| medial cord | medial pectoral nerve | C8, T1 | pectoralis major and pectoralis minor | - |

| medial cord | medial root of the median nerve | C8, T1 | all of the flexors in the forearm except flexor carpi ulnaris and that part of flexor digitorum profundus that supplies the 2nd and 3rd digits

1st and 2nd lumbrical muscles. muscles of the thenar eminence by a recurrent thenar branch |

portions of hand not served by ulnar or radial, i.e skin of the palmar side of the thumb, the index and middle finger, half the ring finger, and the nail bed of these fingers |

| medial cord | medial cutaneous nerve of the arm | C8, T1 | - | front and medial skin of the arm |

| medial cord | medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm | C8, T1 | - | medial skin of the forearm |

| medial cord | ulnar nerve | C7, C8, T1(C7 because it supplies to the Flexor carpi ulnaris) | flexor carpi ulnaris, the medial two bellies of flexor digitorum profundus, the intrinsic hand muscles, except the thenar muscles and the two lateral lumbricals of the hand which are served by the median nerve | the skin of the medial side of the hand and medial one and a half fingers on the palmar side and medial two and a half fingers on the dorsal side |

Function

editThe brachial plexus provides nerve supply to the skin and muscles of the arms, with two exceptions: the trapezius muscle (supplied by the spinal accessory nerve) and an area of skin near the axilla (supplied by the intercostobrachial nerve). The brachial plexus communicates through the sympathetic trunk via gray rami communicantes that join the plexus roots.

The terminal branches of the brachial plexus (musculocutaneous n., axillary n., radial n., median n., and ulnar n.) all have specific sensory, motor and proprioceptive functions.[5][6]

| Terminal Branch | Sensory Innervation | Muscular Innervation |

|---|---|---|

| musculocutaneous nerve | Skin of the anterolateral forearm | Brachialis, biceps brachii, coracobrachialis |

| axillary nerve | Skin of lateral portion of the shoulder and upper arm | Deltoid and teres minor |

| radial nerve | Posterior aspect of the lateral forearm and wrist; posterior arm | Triceps brachii, brachioradialis, anconeus, extensor muscles of the posterior arm and forearm |

| median nerve | Skin of lateral 2/3rd of hand and the tips of digits 1-4 | Forearm flexors, thenar eminence, lumbricals of the hand 1-2 |

| ulnar nerve | Skin of palm and medial side of hand and digits 3-5 | Hypothenar eminence, some forearm flexors, thumb adductor, lumbricals 3-4, interosseous muscles |

Clinical significance

editInjury

editInjury to the brachial plexus may affect sensation or movement of different parts of the arm. Injury can be caused by the shoulder being pushed down and the head being pulled up, which stretches or tears the nerves. Injuries associated with malpositioning commonly affect the brachial plexus nerves, rather than other peripheral nerve groups.[7][8] Due to the brachial plexus nerves being very sensitive to position, there are very limited ways of preventing such injuries. The most common victims of brachial plexus injuries consist of victims of motor vehicle accidents and newborns.[9]

Injuries can be caused by stretching, diseases, and wounds to the lateral cervical region (posterior triangle) of the neck or the axilla. Depending on the location of the injury, the signs and symptoms can range from complete paralysis to anesthesia. Testing the patient's ability to perform movements and comparing it to their normal side is a method to assess the degree of paralysis. A common brachial plexus injury is from a hard landing where the shoulder widely separates from the neck (such as in the case of motorcycle accidents or falling from a tree). These stretches can cause ruptures to the superior portions of the brachial plexus or avulse the roots from the spinal cord. Upper brachial plexus injuries are frequent in newborns when excessive stretching of the neck occurs during delivery. Studies have shown a relationship between a newborn's weight and brachial plexus injuries; however, the number of cesarean deliveries necessary to prevent a single injury is high at most birth weights.[10]

For the upper brachial plexus injuries, paralysis occurs in those muscles supplied by C5 and C6 like the deltoid, biceps, brachialis, and brachioradialis. A loss of sensation in the lateral aspect of the upper limb is also common with such injuries. An inferior brachial plexus injury is far less common but can occur when a person grasps something to break a fall or a baby's upper limb is pulled excessively during delivery. In this case, the short muscles of the hand would be affected and cause the inability to form a full fist position.[11]

To differentiate between preganglionic and postganglionic injury, clinical examination requires that the physician keep the following points in mind. Preganglionic injuries cause loss of sensation above the level of the clavicle, pain in an otherwise insensate hand, ipsilateral Horner's syndrome, and loss of function of muscles supplied by branches arising directly from roots—i.e., long thoracic nerve palsy leading to winging of scapula and elevation of ipsilateral diaphragm due to phrenic nerve palsy.

Acute brachial plexus neuritis is a neurological disorder that is characterized by the onset of severe pain in the shoulder region. Additionally, the compression of cords can cause pain radiating down the arm, numbness, paresthesia, erythema, and weakness of the hands. This kind of injury is common for people who have prolonged hyperabduction of the arm when they are performing tasks above their head.

Sports injuries

editOne sports injury that is becoming prevalent in contact sports, particularly in the sport of American football, is called a "stinger."[12] An athlete can incur this injury in a collision that can cause cervical axial compression, flexion, or extension of nerve roots or terminal branches of the brachial plexus.[13] In a study conducted on football players at United States Military Academy, researchers found that the most common mechanism of injury is, "the compression of the fixed brachial plexus between the shoulder pad and the superior medial scapula when the pad is pushed into the area of Erb's point, where the brachial plexus is most superficial.".[14] The result of this is a "burning" or "stinging" pain that radiates from the region of the neck to the fingertips. Although this injury causes only a temporary sensation, in some cases it can cause chronic symptoms.

Penetrating wounds

editMost penetration wounds require immediate treatment and are not as easy to repair. For example, a deep knife wound to the brachial plexus could damage and/or sever the nerve. According to where the cut was made, it could inhibit action potentials needed to innervate that nerve's specific muscle or muscles.

Injuries during birth

editBrachial plexus injuries can occur during the delivery of newborns when after the delivery of the head, the anterior shoulder of the infant cannot pass below the pubic symphysis without manipulation. This manipulation can cause the baby's shoulder to stretch, which can damage the brachial plexus to varying degrees.[15] This type of injury is referred to as shoulder dystocia. Shoulder dystocia can cause obstetric brachial plexus palsy (OBPP), which is the actual injury to the brachial plexus. The incidence of OBPP in the United States is 1.5 per 1000 births, while it is lower in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland (0.42 per 1000 births).[16] While there are no known risk factors for OBPP, if a newborn does have shoulder dystocia it increases their risk for OBPP 100-fold. Nerve damage has been connected to birth weight with larger newborns being more susceptible to the injury but it also has to do with the delivery methods. Although very hard to prevent during live birth, doctors must be able to deliver a newborn with precise and gentle movements to decrease chances of injuring the child.

Tumors

editTumors that may occur in the brachial plexus are schwannomas, neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

Imaging

editImaging of the Brachial Plexus can be done effectively by using a higher magnetic strength MRI Scanner like 1.5 T or more. It is impossible to evaluate the brachial plexuses with plain Xray, CT and ultrasound scanning can manage to view the plexuses to an extent; hence MRI is preferred in imaging brachial plexus over other imaging modalities due to its multiplanar capability and the tissue contrast difference between brachial plexus and adjacent vessels. The plexuses are best imaged in coronal and sagittal planes, but axial images give an idea about the nerve roots. Generally, T1 WI and T2 WI images are used in various planes for the imaging; but new sequences like MR Myelolography, Fiesta 3D and T2 cube are also used in addition to the basic sequences to gather more information to evaluate the anatomy more.

In anaesthetics

editSee also

editAdditional images

edit-

The brachial plexus surrounds the brachial artery.

-

Nerves in the infraclavicular portion of the right brachial plexus in the axillary fossa.

-

The outermost (distal) part of the brachial plexus shown from a dissected cadaveric specimen.

-

Brachial plexus

-

Mind map showing branches of brachial plexus

-

Spinal cord. Brachial plexus. Cerebrum. Inferior view. Deep dissection.

-

Diagram of the brachial plexus using colour to illustrate the contributions of each nerve root to the branches.

-

The brachial plexus, including all branches of the C5-T1 ventral primary rami. Includes mnemonics for learning the plexus's connections and branches.

-

Mixed fibres of a spinal nerve

References

edit- ^ a b Kawai, H; Kawabata, H (2000). Brachial Plexus Palsy. Singapore: World Scientific. pp. 6, 20. ISBN 9810231393.

- ^ a b c d Saladin, Kenneth (2015). Anatomy and Physiology (7 ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 489–491. ISBN 9789814646437.

- ^ Goel, Shivi; Rustagi, SM; Kumar, A; Mehta, V; Suri, RK (Mar 13, 2014). "Multiple unilateral variations in medial and lateral cords of brachial plexus and their branches". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 47 (1): 77–80. doi:10.5115/acb.2014.47.1.77. PMC 3968270. PMID 24693486.

- ^ Moore, K.L.; Agur, A.M. (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 430–1. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth (2007). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 491. ISBN 9789814646437.

- ^ "Axillary Brachial Plexus Block". www.nysora.com. New York School of Regional Anesthesia. 2013-09-20. Archived from the original on 2017-07-12.

- ^ Cooper, DE; Jenkins, RS; Bready, L; Rockwood Jr, CA (1988). "The prevention of injuries of the brachial plexus secondary to malposition of the patient during surgery". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 228 (228): 33–41. doi:10.1097/00003086-198803000-00005. PMID 3342585.

- ^ Jeyaseelan, L.; Singh, V. K.; Ghosh, S.; Sinisi, M.; Fox, M. (2013). "Iatropathic brachial plexus injury: A complication of delayed fixation of clavicle fractures". The Bone & Joint Journal. 95-B (1): 106–10. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.29625. PMID 23307682.

- ^ Midha, Rajiv (1997). "Epidemiology of Brachial Plexus Injuries in a Multitrauma Population". Neurosurgery. 40 (6): 1182–8, discussion 1188–9. doi:10.1097/00006123-199706000-00014. PMID 9179891.

- ^ Ecker, Jeffrey L.; Greenberg, James A.; Norwitz, Errol R.; Nadel, Allan S.; Repke, John T. (1997). "Birth Weight as a Predictor of Brachial Plexus Injury". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 89 (5): 643–47. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00007-0. PMID 9166293.

- ^ Moore, Keith (2006). Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 778–81. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0.

- ^ Dimberg, Elliot L.; Burns, Ted M. (July 2005). "Management of Common Neurologic Conditions in Sports". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 24 (3): 637–662. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2005.04.002. ISSN 0278-5919.

- ^ Elias, Ilan (2014). "Recurrent burner syndrome due to presumed cervical spine osteoblastoma in a collision sport athlete - a case report". Journal of Brachial Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injury. 02: e61–e65. doi:10.1186/1749-7221-2-13. PMC 1904218. PMID 17553154.

- ^ Cunnane, M (2011). "A retrospective study looking at the incidence of 'stinger' injuries in professional rugby union players". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 45 (15): A19.1–A19. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090606.60. Retrieved 2015-02-12.

- ^ "Brachial Plexus Injuries Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ^ Doumouchtsis, Stergios K.; Arulkumaran, Sabaratnam (2009-09-01). "Are all brachial plexus injuries caused by shoulder dystocia?". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 64 (9): 615–623. doi:10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181b27a3a. ISSN 1533-9866. PMID 19691859.

Bibliography

edit- Saladin, Kenneth (2014). Anatomy and Physiology (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. p. 491.

- Kishner, Stephen. "Brachial Plexus Anatomy". Medscape. WebMD. Retrieved 29 Nov 2015.

External links

edit- Brachial Plexus Injury/Illustration, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

- Learn the Brachial Plexus in Five Minutes or Less by Daniel S. Romm, M.D. and Dennis A. Chu Chu, M.D. [1]

- Video of the dissected axilla and brachial plexus