40°36′N 38°00′E / 40.6°N 38.0°E

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

| Pontos (Πόντος) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient region of Anatolia | |

Region of Pontus | |

| Location | North-eastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) |

| Ethnic Groups | Chalybes, Leukosyroi, Makrones, Mossynoikoi, Muški, Tibarenoi, Laz, Georgians, Armenians, Cimmerians, Pontic Greeks, Persians (from 6th c. BC), Jews, Hemshin, Chepni and Turks[1] (from 11th c.) |

| Historical capitals | Amasia (Amasya), Neocaesarea (Niksar), Sinope (Sinop), Trebizond (Trabzon) |

| Notable rulers | Mithradates Eupator |

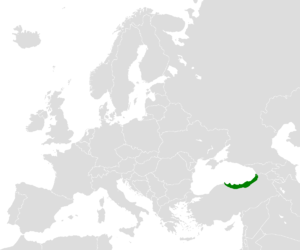

The modern definition of the Pontus: the area claimed for the "Republic of Pontus" after World War I, based on the extent of the six local Greek Orthodox bishoprics. | |

Pontus or Pontos (/ˈpɒntəs/; Greek: Πόντος, romanized: Póntos, lit. 'sea',[2]) is a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in the modern-day eastern Black Sea Region of Turkey. The name was applied to the coastal region and its mountainous hinterland (rising to the Pontic Alps in the east) by the Greeks who colonized the area in the Archaic period and derived from the Greek name of the Black Sea: Εύξεινος Πόντος (Eúxinos Póntos), "Hospitable Sea",[3] or simply Pontos (ὁ Πόντος) as early as the Aeschylean Persians (472 BC) and Herodotus' Histories (circa 440 BC).

Having originally no specific name, the region east of the river Halys was spoken of as the country Ἐν Πόντῳ (En Póntō), lit. "on the [Euxinos] Pontos", and hence it acquired the name of Pontus, which is first found in Xenophon's Anabasis (c. 370 BC). The extent of the region varied through the ages but generally extended from the borders of Colchis (modern western Georgia) until well into Paphlagonia in the west, with varying amounts of hinterland. Several states and provinces bearing the name of Pontus or variants thereof were established in the region in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods, culminating in the late Byzantine Empire of Trebizond. Pontus is sometimes considered as the original home of the Amazons, in ancient Greek mythology and historiography (e. g. by Herodotus and Strabo).

History

editEarly inhabitants

editPontus remained outside the reach of the Bronze Age empires, of which the closest was Great Hatti. The region went further uncontrolled by Hatti's eastern neighbors, Hurrian states like Azzi and (or) Hayasa. In those days, the best any outsider could hope from this region was temporary alliance with a local strongman. The Hittites called the unorganized groups on their northeastern frontier the Kaška. As of 2004 little had been found of them archaeologically.[4]

In the wake of the Hittite empire's collapse, the Assyrian court noted that the "Kašku" had overrun its territory in conjunction with a hitherto unknown group whom they labeled the Muški.[5] Iron Age visitors to the region, mostly Greek, noted that the hinterlands remained disunited, and they recorded the names of tribes: Moskhians (often associated with those Muški),[6] Leucosyri,[7] Mares, Makrones, Mossynoikoi, Tibarenoi,[8] Tzans[9] and Chalybes or Chaldoi.[10]

The Armenian language went unnoted by the Hittites, the Assyrians, and all the post-Hittite nations; an ancient theory – first conjectured by Herodotus – is that its speakers migrated from Phrygia, past literary notice, across Pontus during the early Iron Age. The Greeks, who spoke a closely related Indo-European tongue, followed them along the coast. The Greeks are the earliest long-term inhabitants of the region from whom written records survive. During the late 8th century BC, Pontus further became a base for the Cimmerians, another Indo-European speaking people; however, these were defeated by the Lydians, and became a distant memory after the campaigns of Alyattes.[11]

Since there was so little literacy in northeastern Anatolia[12] until the Persian and Hellenistic era, one can only speculate as to the other languages spoken here. Given that Kartvelian languages remain spoken to the east of Pontus, some are suspected to have been spoken in eastern Pontus during the Iron Age: the Tzans are usually associated with today's Laz.[9]

Ancient Greek colonization

editThe first travels of Greek merchants and adventurers to the Pontus region occurred probably from around 1000 BC, whereas their settlements would become steady and solidified cities only by the 8th and 7th centuries BC as archaeological findings document. This fits in well with a foundation date of 731 BC as reported by Eusebius of Caesarea for Sinope, perhaps the most ancient of the Greek colonies in what was later to be called Pontus.[13] The epical narratives related to the travels of Jason and the Argonauts to Colchis, the tales of Heracles' navigating the Black Sea, and Odysseus' wanderings into the land of the Cimmerians, as well as the myth of Zeus constraining Prometheus to the Caucasus mountains as a punishment for his outwitting the Gods, can all be seen as reflections of early contacts between early Greek colonists and the local, probably Caucasian, peoples. The earliest known written description of Pontus, however, is that of Scylax of Korianda, who in the 7th century BC described Greek settlements in the area.[14]

Persian Empire expansion

editBy the 6th century BC, Pontus had become officially a part of the Achaemenid Empire, which probably meant that the local Greek colonies were paying tribute to the Persians. When the Athenian commander Xenophon passed through Pontus around a century later in 401-400 BC, in fact, he found no Persians in Pontus.[15]

The peoples of this part of northern Asia Minor were incorporated into the third and nineteenth satrapies of the Persian empire.[16] Iranian influence ran deep, illustrated most famously by the temple of the Persian deities Anaitis, Omanes, and Anadatos at Zela, founded by victorious Persian generals in the 6th century BC.[17]

Kingdom of Pontus

editThe Kingdom of Pontus extended generally to the east of the Halys River. The Persian dynasty which was to found this kingdom had during the 4th century BC ruled the Greek city of Cius (or Kios) in Mysia, with its first known member being Ariobarzanes I of Cius and the last ruler based in the city being Mithridates II of Cius. Mithridates II's son, also called Mithridates, would proclaim himself later Mithridates I Ktistes of Pontus.

As the Encyclopaedia Iranica states, the most famous member of the family, Mithradates VI Eupator, although undoubtedly presenting himself to the Greek world as a civilized philhellene and new Alexander, also paraded his Iranian background: he maintained a harem and eunuchs in true Oriental fashion; he gave all his sons Persian names; he sacrificed spectacularly in the manner of the Persian kings at Pasargadae (Appian, Mith. 66, 70); and he appointed “satraps” (a Persian title) as his provincial governors.[18] Iranica further states, and although there is only one inscription attesting it, he seems to have adopted the title “king of kings.” The very small number of Hellenistic Greek inscriptions that have been found anywhere in Pontus suggest that Greek culture did not substantially penetrate beyond the coastal cities and the court.[18]

During the troubled period following the death of Alexander the Great, Mithridates Ktistes was for a time in the service of Antigonus, one of Alexander's successors,[19] and successfully maneuvering in this unsettled time managed, shortly after 302 BC, to create the Kingdom of Pontus which would be ruled by his descendants mostly bearing the same name, until 64 BC. Thus, this Persian dynasty managed to survive and prosper in the Hellenistic world while the main Persian Empire had fallen.

This kingdom reached its greatest height under Mithridates VI or Mithridates Eupator, commonly called the Great, who for many years carried on war with the Romans. Under him, the realm of Pontus included not only Pontic Cappadocia but also the seaboard from the Bithynian frontier to Colchis, part of inland Paphlagonia, and Lesser Armenia.[19] Despite ruling Lesser Armenia, King Mithridates VI was an ally of Armenian King Tigranes the Great, to whom he married his daughter Cleopatra.[20] Eventually, however, the Romans defeated both King Mithridates VI and his son-in-law, Armenian King Tigranes the Great, during the Mithridatic Wars, bringing Pontus under Roman rule.[21]

Roman province

editWith the subjugation of this kingdom by Pompey in 64 BC, little changed in the daily lives of either the oligarchies that controlled the cities or for the common people there and in the hinterland, though the meaning of the name Pontus underwent a change.[19] Part of the kingdom was now annexed to the Roman Empire, being united with Bithynia in a double province called Pontus and Bithynia: this part included only the seaboard between Heraclea (today Ereğli) and Amisus (Samsun), the ora Pontica.[19] The larger part of Pontus, however, was included in the province of Galatia.[21]

Hereafter the simple name Pontus without qualification was regularly employed to denote the half of this dual province, especially by Romans and people speaking from the Roman point of view; it is so used almost always in the New Testament.[19] The eastern half of the old kingdom was administered as a client kingdom together with Colchis. Its last king was Polemon II.

In AD 62, the country was constituted by Nero a Roman province. It was divided into the three districts: Pontus Galaticus in the west, bordering on Galatia; Pontus Polemoniacus in the centre, so called from its capital Polemonium; and Pontus Cappadocicus in the east, bordering on Cappadocia (Armenia Minor). Subsequently, the Roman Emperor Trajan moved Pontus into the province of Cappadocia itself in the early 2nd century AD.[21] In response to a Gothic raid on Trebizond in 287 AD, the Roman Emperor Diocletian decided to break up the area into smaller provinces under more localized administration.[9]

With the reorganization of the provincial system under Diocletian (about AD 295), the Pontic districts were divided up between three smaller, independent provinces within the Dioecesis Pontica:[9][19]

- Galatian Pontus, also called Diospontus, later renamed Helenopontus by Constantine the Great after his mother. It had its capital at Amisus, and included the cities of Sinope, Amasia, Andres, Ibora, and Zela as well.

- Pontus Polemoniacus, with its capital at Polemonium (also called Side), and including the cities of Neocaesarea, Argyroupolis, Comana, and Cerasus as well.

- Cappadocian Pontus, with its capital at Trebizond, and including the small ports of Athanae and Rhizaeon. This province extended all the way to Colchis.

Byzantine province and theme

editThe Byzantine Emperor Justinian further reorganized the area in 536:

- Pontus Polemoniacus was dissolved, with the western part (Polemonium and Neocaesarea) going to Helenopontus, Comana going to the new province of Armenia II, and the rest (Trebizond and Cerasus) joining the new province of Armenia I Magna with its capital at Justinianopolis.[9]

- Helenopontus gained Polemonium and Neocaesarea, and lost Zela to Armenia II. The provincial governor was relegated to the rank of moderator.

- Paphlagonia absorbed Honorias and was put under a praetor.

By the time of the early Byzantine Empire, Trebizond became a center of culture and scientific learning. In the 7th century, an individual named Tychicus returned from Constantinople to establish a school of learning. One of his students was the early Armenian scholar Anania of Shirak.[22]

Under the Byzantine Empire, the Pontus came under the Armeniac Theme, with the westernmost parts (Paphlagonia) belonging to the Bucellarian Theme. Progressively, these large early themes were divided into smaller ones, so that by the late 10th century, the Pontus was divided into the themes of Chaldia, which was governed by the Gabrades family,[22] and Koloneia. After the 8th century, the area experienced a period of prosperity, which was brought to an end only by the Seljuk conquest of Asia Minor in the 1070s and 1080s. Restored to the Byzantine Empire by Alexios I Komnenos, the area was governed by effectively semi-autonomous rulers, like the Gabras family of Trebizond.

The region was secured militarily from the 11th through the 15th centuries with a vast network of sophisticated coastal fortresses.[23]

Empire of Trebizond

editFollowing Constantinople's loss of sovereignty to the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Pontus retained independence as the Empire of Trebizond under the Komnenos dynasty. Through a combination of geographic remoteness and adroit diplomacy, this remnant managed to survive, until it was conquered by the Ottomans in 1461 after the Fall of Constantinople itself. This political adroitness included becoming a vassal state at various times to both Georgia and to various inland Turkic rulers. In addition, the Empire of Trebizond became a renowned center of culture under its ruling Komnenos dynasty.[24]

Ottoman vilayet

edit| Distribution of Millets in Trebizond Vilayet[25] | |||||||

| Source | Muslims | Greeks | Armenians | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official Ottoman Statistics, 1910 | 1,047,889 72.56% |

351,104 24.31% |

45,094 3.12% |

1,444,087 | |||

| Ecumenical Patriarchate Statistics, 1912 | 957,866 70.33% |

353,533 25.96% |

50,624 3.72% |

1,362,026 | |||

Under the subsequent Ottoman rule which began with the fall of Trebizond, particularly starting from the 17th century, some of the region's Pontic Greeks became Muslim through the Devşirme system. But at the same time some valleys inhabited by Greeks converted voluntarily, most notably those in the Of valley. Large communities (around 25% of the population) of Christian Pontic Greeks remained throughout the area (including Trabezon and Kars in northeastern Turkey/the Russian Caucasus) until the 1920s, and in parts of Georgia and Armenia until the 1990s, preserving their own customs and dialect of Greek. One group of Islamicized Greeks were called the Kromli, but were suspected of secretly having remained Christians. They numbered between 12,000 and 15,000 and lived in villages including Krom, Imera, Livadia, Prdi, Alitinos, Mokhora, and Ligosti.[26] Many of the Islamized Greeks continued speaking their language, known for its unique preservation of characteristics of Ancient Greek and still today there are some in the Of valley that speak the local Ophitic dialect.

Republic of Pontus

editThe Republic of Pontus (Greek: Δημοκρατία του Πόντου, romanized: Dimokratía tou Póntou) was a proposed Pontic Greek state on the southern coast of the Black Sea. Its territory would have encompassed much of historical Pontus and today forms part of Turkey's Black Sea Region. The proposed state was discussed at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, but the Greek government of Eleftherios Venizelos feared the precarious position of such a state and so it was included instead in the larger proposed state of Wilsonian Armenia. Neither state came into existence and the Pontic Greek population was subjected to genocide and expelled from Turkey after 1922 and resettled in the Soviet Union or in Macedonia. This state of affairs was later formally recognized as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

Present

editThe Black Sea Region (Turkish: Karadeniz Bölgesi), comprising all or parts of 22 provinces, is one of Turkey's seven census-defined geographical regions. It encompasses but is larger than historic Pontus.

Religion

editMentioned thrice in the New Testament, inhabitants of Pontus were some of the first converts to Christianity. Acts 2:9 mentions them present in Jerusalem on the Day of Pentecost; Acts 18:2 mentions a Jewish tentmaker from Pontus, Aquila, who was then living in Corinth with his wife Priscilla, who had both converted to Christianity, and in 1 Peter 1:1, Peter the Apostle addresses the Pontians in his letter as the "elect" and "chosen ones".

As early as the First Council of Nicea, Trebizond had its own bishop. Subsequently, the Bishop of Trebizond was subordinated to the Metropolitan Bishop of Poti. Then during the 9th century, Trebizond itself became the seat of the Metropolitan Bishop of Lazica.[10]

Notable Pontians

edit- Diogenes of Sinope (c. 408–323 BC), Greek philosopher from Sinope, one of founders of Cynic philosophy

- Mithridates VI Eupator (c. 135 BC – 63 BC), Pontic King, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents.

- Strabo (c. 64 BC – 24 AD), Greek historian, geographer, and philosopher, native from Amaseia

- Marcion of Sinope (c. 85 – c. 160 AD), early Christian theologian

- Evagrius Ponticus (345–399 AD), Greek theologian and monk

- Basilios Bessarion (1403–1472), Greek scholar, Roman Catholic cardinal and titular Latin Patriarch of Constantinople

- Alexander Ypsilantis (1792–1828), Greek military commander and national hero of the 19th century

- A. I. Bezzerides (1908–2007), American novelist and screenwriter, born in Samsun

- Antonis Fosteridis (1912–1979), Greek nationalist, anticommunist partisan during WWII

- Stelios Kazantzidis (1931–2001), Greek singer of Greek popular music, or Laïkó

- Chrysanthos Theodoridis (1933–2005), singer

- Mike Lazaridis (b. 1961), CEO of Research in Motion and creator of BlackBerry phones

- Melina Aslanidou (1974–present), Greek singer

- Pantelis Pantelidis (1983–2016), Greek singer

- Apolas Lermi (1986-present), Greco-Turkish folk musician

See also

edit- Amaseia, Ancient capital of Pontus

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

- Caucasus Greeks

- Greek genocide

- Lazistan

- Pontic Greek

- Republic of Pontus

Citations

edit- ^ Meeker, Michael E. (1971). "The Black Sea Turks: Some Aspects of Their Ethnic and Cultural Background". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2 (4): 318–345. doi:10.1017/S002074380000129X. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 162721. S2CID 162611158. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ πόντος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- ^ Εὔξεινος, William J. Slater, Lexicon to Pindar, on Perseus.

- ^ Roger Matthews (December 2004). "Landscapes of Terror and Control: Imperial Impacts in Paphlagonia". Near Eastern Archaeology. 67 (4): 200–211. doi:10.2307/4132387. JSTOR 4132387. S2CID 161960753.

- ^ Records of Tiglath-Pileser I apud RD Barnett (1975). "30". The Cambridge Ancient History. pp. 417f., 420.

- ^ So the 1877 translation of "Sargon's Great Inscription in the Palace of Khorsabad", http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/Sargon.html Archived 2015-06-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Meyer, Geschichte d. Königr. Pontos (Leipzig: 1879) [dead link]

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2009). "Armenians on the Black Sea: The Province of Trebizond". In Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.). Armenian Pontus: The Trebizond-Black Sea Communities. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, Inc. pp. 40 f. ISBN 978-1-56859-155-1.

- ^ a b c d e Hewsen, 43.

- ^ a b Hewsen, 46.

- ^ Kristensen, Anne Katrine Gade (1988). Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from?: Sargon II, and the Cimmerians, and Rusa I. Copenhagen Denmark: The Royal Danish Academy of Science and Letters.

- ^ "Ancient Turkey: History of Asia Minor".

- ^ Hewsen, 39 f.

- ^ Hewsen, 39.

- ^ Hewsen, 40.

- ^ Herodotus 3.90-94.

- ^ Strabo 11.8.4 C512; 12.3.37 C559.

- ^ a b electricpulp.com. "PONTUS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ a b c d e f This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Anderson, John George Clark (1911). "Pontus". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–71.

- ^ Hewsen, 41 f.

- ^ a b c Hewsen, 42.

- ^ a b Hewsen, 47.

- ^ Robert W. Edwards, “The Garrison Forts of the Pontos: A Case for the Diffusion of the Armenian Paradigm,” Revue des Études Arméniennes 19, 1985, pp. 181-284, pls.1-51b.

- ^ Hewsen, 48 f.

- ^ Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6.

- ^ Hewsen, 54.

General and cited sources

edit- Bryer, Anthony A. M. (1980), The Empire of Trebizond and the Pontos, London: Variorum Reprints, ISBN 0-86078-062-7

- Ramsay MacMullen, 2000. Romanization in the Time of Augustus (Yale University Press)

External links

edit- History of Pontus

- The term Euxinus Pontus Archived 2014-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Where East Meets West