Powerlifting is a competitive strength sport that consists of three attempts at maximal weight on three lifts: squat, bench press, and deadlift. As in the sport of Olympic weightlifting, it involves the athlete attempting a maximal weight single-lift effort of a barbell loaded with weight plates. Powerlifting evolved from a sport known as "odd lifts", which followed the same three-attempt format but used a wider variety of events, akin to strongman competition. Eventually, odd lifts became standardized to the current three.

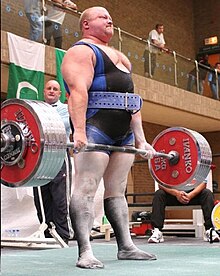

The deadlift being performed by 2009 IPF World Champion Dean Bowring | |

| Highest governing body | International Powerlifting Federation |

|---|---|

| First played | 1950s, United States of America |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Mixed-sex | No |

| Type | Strength sport |

| Equipment | Barbells, weight plates, collars, chalk, heel-elevated shoes, barefoot shoes, belt, knee sleeves & wrist wraps |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | No |

| Paralympic | 1984 – present |

| World Games | 1981 – present (Equipped) 2025 – present (Raw) |

In competition, lifts may be performed equipped or unequipped (typically referred to as 'classic' or 'raw' lifting in the IPF specifically). Equipment in this context refers to a supportive bench shirt or squat/deadlift suit or briefs. In some federations, knee wraps are permitted in the equipped but not unequipped division; in others, they may be used in both equipped and unequipped lifting. Weightlifting belts, knee sleeves, wrist wraps, and special footwear may also be used, but are not considered when distinguishing equipped from unequipped lifting.[1]

Competitions take place across the world. Powerlifting has been a Paralympic sport (bench press only) since 1984 and, under the IPF, is also a World Games sport. Local, national and international competitions have also been sanctioned by other federations operating independently of the IPF.

History

editEarly history

editThe roots of powerlifting are found in traditions of strength training stretching back as far as the ancient Mayan civilizations and ancient Persian times. The idea of powerlifting originated in ancient Greece, as men lifted stones to prove their strength and manhood.[2] The modern sport originated in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1950s.[3] Previously, the weightlifting governing bodies in both countries had recognized various "odd lifts" for competition and record purposes.[4] During the 1950s, Olympic weightlifting declined in the United States, while strength sports gained many new followers. People did not like the Olympic lifts Clean and Press, Snatch and Clean and Jerk.[5] In 1958, the National Weightlifting Committee of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) decided to begin recognizing records for odd lifts.[6] The first national competition was held in September 1964 under the auspices of the York Barbell Company.[7] York Barbell owner Bob Hoffman had been a longtime adversary of the sport, but his company was now making powerlifting equipment to make up for the sales it had lost on Olympic equipment.[6]

During the late 1950s, Hoffman's influence on Olympic lifting and his predominately Olympics-focused magazine Strength and Health were beginning to come under increasing pressure from Joe Weider's organization.[6] In order to combat the growing influence of Weider, Hoffman started another magazine, Muscular Development, which would be focused more on bodybuilding and the fast-growing interest in odd lift competitions.[8] The magazine's first editor was John Grimek.[9] During the late 1950s and early 1960s, various odd lift events gradually developed into the specific lifts of the bench press, squat, and deadlift, and were lifted in that order.[10] Hoffman became more and more influential in the development of this new lifting sport and organized the Weightlifting Tournament of America in 1964, effectively the first USA National championships. In 1965, the first named USA National Championships were held.[10] During the same period, lifting in Britain also had factions. In the late 1950s, because members of the ruling body (BAWLA, the British Amateur Weight Lifters' Association) were only interested in the development of Olympic lifting, a breakaway organization called the Society of Amateur Weightlifters had been formed to cater for the interests of lifters who were not particularly interested in Olympic lifting.[6]

Although at that time there were 42 recognized lifts, the "Strength Set" (biceps curl, bench press, and squat) soon became the standard competition lifts, and both organizations held Championships on these lifts (as well as on the Olympic lifts) until 1965. In 1966, the Society of Amateur Weightlifters rejoined BAWLA. The bicep curl was replaced with the deadlift to fall in line with the American lifts.[6] The first British Championship was held in 1966.[11] During the late 1960s and at the beginning of the 1970s, various international contests were held. At the same time, in early November of each year and to commemorate Hoffman's birthday, a prestigious lifting contest was held. In 1971, it was decided to make this event the "World Weightlifting Championships".[6] The event was held at 10 AM on 6 November 1971, in York, Pennsylvania. Most of the athletes were American lifters, since teams were not formed yet. There were also four British athletes, and one athlete from Jamaica.[12] All of the referees were American. Weights were in pounds. The lifting order was "rising bar", and the first lift was the bench press. There was no such thing as a bench shirt or squat suit, and various interpretations were held regarding the use and length of knee wraps and weightlifting belts. The IPF rules system did not exist yet, nor had world records been established.[6][12]

In 1972, the second AAU World Championships were held on 10 and 11 November. There were eight athletes from Great Britain, six from Canada, six from Puerto Rico, three from Zambia, and one from the West Indies. With 67 lifters in total, 47 athletes were Americans. Lifts were measured in pounds, and the bench press was the first lift.[6][13][14]

IPF and after

editThe International Powerlifting Federation was formed in November of 1972. The inaugural IPF World Championships was held in York on November of 1973. There were 47 entrants: one Swedish athlete, one Puerto Rican athlete, two Canadian athletes, one West Indian athlete, eight British athletes, and 34 American athletes.[15][16] 1974 was the first time that teams were selected in advance, as well as the inclusion of the 52 kilogram weight class.[17] In 1975, the World Championships was held outside America for the first time, at the town hall in Birmingham, hosted by Vic Mercer.[18]

The establishment of the IPF in 1973 spurred the establishment of the EPF (European Powerlifting Federation) in May 1977.[19] Since it was closely associated with bodybuilding and women had been competing as bodybuilders for years, powerlifting was opened to them. The first U.S. national championships for women were held in 1978. The IPF added women's competition in 1980.[20] In the US, the Amateur Sports Act of 1978 required that each Olympic or potential Olympic sport must have its own national governing body by November 1980.[21] As a result, the AAU lost control of every amateur sport. The USPF was founded in 1980 as the new national governing body for American powerlifting.[22] In 1981, the American Drug Free Powerlifting Association (ADFPA), led by Brother Bennett, became the first federation to break away from the USPF, citing the need to implement effective drug testing in the sport.[23] In 1982, drug testing was introduced to the IPF, although the USPF championships that year did not have drug testing.[24]

The IPF's push for drug testing was resisted by several American lifters. In 1982, Larry Pacifico and Ernie Frantz founded the American Powerlifting Federation (APF), which advertised its categorical opposition to all drug testing.[23]

In 1984, powerlifting was included into the Paralympic Games for men with spinal cord injuries. At the 2000 Paralympic Games in Sydney, women were invited to participate in powerlifting. Both men and women are allowed to compete in 10 weight classes respectively.[25][26]

In 1987, the American Powerlifting Association (APA) and World Powerlifting Alliance (WPA) were formed by Scott Taylor.[27] The APA offer both drug tested and untested categories in most of their competitions.[28] As of 2024, the WPA has over 60 affiliate nations.[29]

The USPF failed to conform to IPF demands and was expelled from the international body in 1997, with the ADFPA, now named USA Powerlifting (USAPL), taking its place (now replaced by Powerlifting America).[30] Despite the trend towards federations, each with their own rules and standards of performance, some powerlifters have attempted to bring unity to the sport. For example, 100% RAW promoted unequipped competition and merged with another federation, Anti-Drug Athletes United (ADAU), in 2013.[31] The Revolution Powerlifting Syndicate (RPS), founded by Gene Rychlak in 2011, was considered a move towards unity, as the RPS breaks the tradition of charging lifters membership fees to a specific federation in addition to entry fees for each competition.[32] Some meet promoters have sought to bring together top lifters from different federations, outside existing federations' hierarchy of local, regional, national and international meets; a prominent example of this is the Raw Unity Meet (RUM), held annually since 2007.[33]

Developments in equipment and rules

editAs new equipment was developed, it came to distinguish powerlifting federations from one another. Weightlifting belts and knee wraps (originally simple Ace bandages) predated powerlifting, but in 1983 John Inzer invented the first piece of equipment distinct to powerlifters—the bench shirt.[34] Bench shirts and squat/deadlift suits (operating on the same principle) became ubiquitous in powerlifting, but only some federations adopted the latest and most supportive canvas, denim, and multiply polyester designs, while others such as the IPF maintained more restrictive rules on which supportive equipment could be used.[35] The Monolift, a rack in which the bar catchers swing out and eliminate the walkout portion of the squat, was invented by Ray Madden and first used in competition in 1992.[36] This innovation was adopted by some federations and forbidden in others. Other inventions included specialized squat bars and deadlift bars, moving away from the IPF standard of using the same bar for all three lifts.[37][38]

The rules of powerlifting have also evolved and differentiated. For example, in ADFPA/USAPL competition, the "press" command on the bench press was used, not used,[39] and then used again, following a 2006 IPF motion to reinstate this rule.[40] IPF rules also mandate a "start" command at the beginning of the bench press. Many other federations, for example, the Natural Athlete Strength Association (NASA), have never used the "start" command.[41] As a further example of diversifying rules of performance, in 2011 the Southern Powerlifting Federation (SPF) eliminated the "squat" command at the beginning of the squat.[42] Most federations also now allow the sumo deadlift, which the athletes foot position is outside their grip position. Many communities and federations do not class the sumo variation as a technical deadlift.[43] Another rule change into effect from the IPF, is the bench press elbow depth rule, established in 2022 and into effect at the start of 2023. This rule, similar to squat depth, requires the bottom surface of the elbows to be in line with or below the top surface of the shoulder joint.[44]

Supportive equipment

editIn powerlifting, supportive equipment refers to supportive shirts, briefs, suits, and sometimes knee wraps made of materials that store elastic potential energy and thereby assist the three lifts contested in powerlifting.[45] Some federations allow single-ply knee sleeves, and wraps for wrists in raw competition.[46] Straps are also used in deadlift training in case of a weak grip, but are not allowed by any federations in official competitions.[47] A weight lifting belt is the only supportive equipment that is allowed by all federations in raw competition.[48] The use of supportive equipment distinguishes 'equipped' and 'unequipped' (also known as 'raw') divisions in the sport, and 'equipped' and 'unequipped' records in the competition lifts. The wide differences between equipped and unequipped records in the squat and bench press suggest that supportive equipment confers a substantial advantage to lifters in these disciplines.[49] This is less evident in the case of the deadlift, where the lack of an eccentric component to the lift minimizes how much elastic energy can be stored in a supportive suit.[50] Supportive equipment should not be confused with the equipment on which the lifts are performed, such as a bench press bench, or conventional or monolift stand for squat or the barbell and discs.[51][52] Chalk is commonly used by lifters to dry the hands to reduce blisters, slipping and improve grip strength, as the contents of the chalk is made out of magnesium carbonate. Chalk can also be added to the shoulders for squatting,[53] on the back for bench pressing to reduce sliding, and on the hands to grip the barbell on the bench press and deadlift.[54][55]

Principles of operation

editSupportive equipment is used to increase the weight lifted in powerlifting exercises.[49][56][57] A snug garment is worn over a joint or joints (such as the shoulders or hips). This garment deforms during the downward portion of a bench press or squat, or the descent to the bar in the deadlift, storing elastic potential energy.[58] On the upward portion of each lift, the elastic potential energy is transferred to the barbell as kinetic energy, aiding in the completion of the lift.[45][59] Some claim that supportive equipment prevents injuries by compressing and stabilizing the joints over which it worn.[59] For example, the bench shirt is claimed to support and protect the shoulders.[49] Critics point out that the greater weights used with supportive equipment and the equipment's tendency to change the pattern of the movement may compromise safety, as in the case of the bar moving towards the head during the upward portion of the shirted bench press.[60]

Squat suit material and construction

editDifferent materials are used in the construction of supportive equipment. Squat suits may be made of varying types of polyester, or of canvas. The latter fabric is less elastic, and therefore considered to provide greater 'stopping power' at the bottom of the movement but less assistance with the ascent.[57] Bench shirts may be made of polyester or denim,[56] where the denim again provides a less-elastic alternative to the polyester. Knee wraps are made of varying combinations of cotton and elastic.[61] Supportive equipment can be constructed in different ways to suit the lifters' preferences. A squat suit may be constructed for a wide or a narrow stance;[62] and a bench shirt may be constructed with 'straight' sleeves (perpendicular to the trunk of the lifter) or sleeves that are angled towards the abdomen.[63] The back of the bench shirt may be closed or open, and the back panel may or may not be of the same material as the front of the shirt.[64] Similarly, 'hybrid' squat suits can include panels made from canvas and polyester, in an effort to combine the strengths of each material. When two or more panels overlay one another in a piece of supportive equipment, that equipment is described as 'multi-ply', in contrast to 'single-ply' equipment made of one layer of material throughout.[57]

Raw powerlifting

editRaw powerlifting, also called classic or unequipped powerlifting has been codified in response to the proliferation and advancement of bench shirts and squat/deadlift suits. The 100% RAW federation was founded in 1999;[65] within a decade, many established federations came to recognize "raw" divisions, in addition to their traditional (open) divisions permitting single-ply or multi-ply equipment. United Powerlifting Association (UPA) established a standard for raw powerlifting in 2008,[66] and USAPL held the first Raw Nationals in the same year.[67] Eventually, IPF recognized raw lifting with the sanction of a "Classic Unequipped World Cup" in 2012 and published its own set of standards for raw lifting.[68] By this time, the popularity of raw lifting had surged to the point where raw lifters came to predominate over equipped lifters in local meets.[69][70]

The use of knee sleeves in unequipped powerlifting has brought about much debate as to whether certain neoprene knee sleeves can assist a lifter during the squat.[71] Some lifters purposely wear knee sleeves that are excessively tight and have been known to use plastic bags and have others to assist them get their knee sleeves on.[72] This led to the IPF mandating that lifters put on their knee sleeves unassisted.[73]

Equipped powerlifting

editEquipped lifters compete separately from raw lifters. Equipped athletes will wear a squat suit, knee wraps, a bench shirt, and a deadlift suit.[74]

Equipped squats

editFor the squats, a squat suit is used for the event. Squat suits are typically made of an elastic-like material, and a single-ply polyester layer.[75] This allows a competitor to spring out of the bottom of a squat (called "pop out of the hole" in Powerlifting circles) by maintaining rigidity, keeping the athlete upright and encouraging their hips to remain parallel with the floor.[76] This allows lifters to lift more weight than would normally be possible without the suit.[77] There are also multi-ply suits giving the lifter more rigidity, like that of a traditional canvas suit, with the same pop as a single-ply suit or briefs but are exponentially harder to use, and are usually reserved for the top lifters.[78] During the squat, lifters also tend to wear knee wraps.[74] Even though knee wraps will be a sub-classification of raw lifting, it will still be worn by equipped lifters.[79] A raw lifter who would squat in knee wraps will have the weight lifted noted as "with wraps" to distinguish from raw lifters using knee sleeves.[80] Knee wraps are made out of similar elastic material as wrist wraps.[81][82] They are wrapped around the lifters knees tightly. The knee wraps are wrapped in a spiral or diagonal method.[83] The knee wraps build elastic energy during the eccentric part of the squat and once the lifter has hit proper depth the lifter will start the concentric part of the movement releasing this elastic energy and using it to help them move the weight upwards. It gives the lifter more spring, or pop out of the hole of the squat resulting in a heavier and faster squat.[84]

Equipped bench press

editFor the bench press, there are single-ply and multi-ply bench shirts that work similarly to a squat suit.[85][86] It acts as artificial pectoral muscles and shoulder muscles for the lifter. It resists the movement of the bench press by compressing and building elastic energy. When the bar is still and the official gives the command to press the compression and elastic energy of the suit aids in the speed of the lift, and support of the weight that the athlete would not be able to provide without the bench shirt.[87][88]

Equipped deadlift

editFor the deadlift, deadlift suits are used for the event. There are single-ply and multi-ply deadlift suits. The elastic energy is built when the lifter goes down to set up and place its grip on the bar before the deadlift attempt. The deadlift suit aids core and spine stability and can increase the speed off the floor at the beginning of the lift. However, deadlift suits are least likely to carry over additional weight in comparison to equipped squatting and equipped bench pressing.[74][86][89]

Classes and categories

editWeight classes:

Most powerlifting federations use the following weight classes:[90][91][92]

Men: -52 kg, -56 kg, -60 kg, -67.5 kg, -75 kg, -82.5 kg, -90 kg, -100 kg, -110 kg, -125 kg, -140 kg, 140 kg+

Women: -44 kg, -48 kg, -52 kg, -56 kg, -60 kg, -67.5 kg, -75 kg, -82.5 kg, -90 kg, 90 kg+

IPF weight classes:

In 2010, the IPF introduced the following new weight classes effective January 1, 2011:[93]

Men: -53 kg (sub-junior/junior), -59 kg, -66 kg, -74 kg, -83 kg, -93 kg, -105 kg, -120 kg, 120 kg+

Women: -43 kg (sub-junior/junior), 47 kg, -52 kg, -57 kg, -63 kg, -72 kg, -84 kg, 84 kg+

In 2020, the IPF announced the 72 kg weight class would be replaced with the 69 and 76 kg weight class effective January 1, 2021.[94]

Age categories

Age categories are depended on the federation.

The IPF uses the following age categories: sub-junior (14–18), junior (19–23), open (any age), masters 1 (40–49), masters 2 (50–59), masters 3 (60–69), masters 4 (70+).[95]

Age categories are dependent on the year of the participant's birth. For example, if an athlete turns 18 years old in July, the athlete is considered an 18-year-old sub-junior throughout the calendar year.[96] Other federations typically break the Masters categories down to 5-year increments, for example, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, etc.[97] Some federations also include a sub-master class from 33 (or 35) to 39.[97]

Competition

editA powerlifting competition takes place as follows:

Each competitor is allowed three attempts on each of the squat, bench press, and deadlift, depending on their standing and the organization they are lifting in. The lifter's best valid attempt on each lift counts toward the competition total. For each weightclass, the lifter with the highest total wins. In many meets, the lifter with the highest total relative to their weight class also wins. If two or more lifters achieve the same total, the lighter lifter ranks above the heavier lifter.[98]

Competitors are judged against other lifters of the same sex, weight class, and age.[99][100] Comparisons of lifters and scores across different weight classes can also be made using handicapping systems. World federations use the following ones: IPF GL Points,[101] Glossbrenner,[102] Reshel,[103] Outstanding Lifter,[104] Schwartz/Malone,[105] Siff;[106] for the junior age categories, Foster coefficient is mostly used;[107] for the masters age categories, McCulloch or Reshel coefficients are mostly used.[107] Winner of a competition based on an official coefficient used by presiding world federation is called best lifter.[108]

Events

editIn a powerlifting competition, sometimes referred to as standard competition, there are three events: bench press, squat and deadlift. Placing is achieved via combined total.[109] Some variations of this are found at some meets such as "push-pull only" meets where lifters only compete in the bench press and deadlift, with the bench press coming first and the deadlift after.[110] Single lift meets are often held for the bench press and the deadlift.[111][112]

At a meet, the events will follow in order: squat, then bench press, and the deadlift will be the final lift of the meet.[109]

Rules

editSquat

editThere are two types depending on equipment used: conventional stand and monolift stand.[113]

The squat starts with the lifter standing erect and the bar loaded with weights resting on the lifter's shoulders or traps. A high bar and low bar position can be used.[114] At the referee's command, the squat begins. The lifter creates a break in the hips, bends their knees and drops into a squatting position. The lifter then ascends back to an erect position. At the referee's command, the bar is returned to the rack and the lift is completed.[115]

After removing the bar from the racks while facing the front of the platform, the lifter may move forward or backward to establish the lifting position. The bar shall be held horizontally across the shoulders with the hands and/or fingers gripping the bar, and the feet flat upon the platform with the knees locked. The lifter shall wait in this position for the head referee's signal to rack the weights.[115]

The lifter will be allowed only one commencement signal per attempt. The lifter may be given an additional attempt at the same weight at the head referee's discretion if failure in an attempt was due to any error by one or more of the spotters or by misload.[115]

Causes for disqualification

edit- Failure to observe the head referee's signals at the commencement or completion of a squat.[116]

- Double bouncing at the bottom of the squat.[117]

- Failure to assume an erect position with knees locked at the end of the squat.[117]

- Any downward movement during the squat ascent.[117]

- Movement of the feet laterally, backward or forward that would constitute a step or stumble after given the 'squat' command and before the 'rack' command.[116]

- Failure to squat to depth.[a]

- Contact with the bar by the spotters between the referee's signals.[116]

- Contact of elbows or upper arms with the legs.[116]

- Any dropping or dumping of the bar.[116]

Bench press

editWith the lifter resting on the bench, the lifter takes the loaded bar at arm's length. At the discretion of the referee's signal, the lifter lowers the bar to the chest. When the bar becomes motionless on the chest, the referee gives a press command. Then the referee will call 'rack' and the lift is completed as the weight is returned to the rack.[120][121]

The bench equipment will be placed on the platform with the head facing the front or angled up to 45 degrees. The head referee will be positioned on the head side of the bench press discipline.[122]

To achieve firm footing, a lifter of any height may use discs or blocks to build up the surface of the platform. Whichever method is chosen, the shoes must be in a solid contact with the surface.[122]

A lift off may be used by the discretion of the lifter to arm's length. A designated spotter, having provided a centre lift off, must immediately clear the area in front of the head referee. If the personal spotter does not immediately leave the platform area and/or is in any way which impedes the head referees' responsibilities, the referees may determine that the lift is unacceptable, and be declared "no lift" by the referees and given three red lights.[122][123]

Causes for disqualification

edit- Failure to observe the referee's signals at the commencement or completion of the lift.[116]

- Any change in the elected position such as shoulders, glutes, and head after the 'start' and before the 'rack' command.[116]

- Allowing the bar to sink into the chest after receiving the referee's signal.[116]

- Pronounced uneven extension of the arms during or at the completion of the lift.[124]

- Any downward motion of the bar during the course of being pressed out.[117]

- Contact with the bar by the spotters between the referee's signals.[116]

- Any contact of the lifter's shoes with the bench or its supports.[116]

- Deliberate contact between the bar and the bar rest uprights during the lift to assist the completion of the press.[116]

- Failure to lower both elbow joints to the level with or below the top surface of both shoulder joints.[125]

Deadlift

editIn the deadlift, the lifter may choose a conventional stance or sumo stance.[126] The lifter grasps the loaded bar which is resting on the platform floor. The lifter pulls the weights off the floor and assumes an erect position. The knees must be locked and the shoulders must be back, with the weight held by the lifter's hands. At the referee's command, the bar will be returned to the floor under the control of the lifter.[127]

The bar must be laid horizontally in front of the lifter's feet, gripped with an optional grip in both hands, and lifted until the lifter is standing erect. Any raising of the bar or any deliberate attempt to do so will count as an attempt.[128]

Causes for disqualification

edit- Any downward motion of the bar before lockout.[117]

- Failure to stand erect.[125]

- Failure to lock the knees while standing erect.[125]

- Supporting the bar on the thighs during the performance of the lift.[117][b]

- Movement of the feet laterally, backward or forward that would constitute a step or stumble.[116]

- Lowering the bar before receiving the head referee's signal.[116]

- Lowering the bar to the platform without maintaining control with both hands.[116]

Training

editWeight training

editPowerlifters practice weight training to improve performance in the three competitive lifts—the squat, bench press and deadlift. Weight training routines used in powerlifting are extremely varied. For example, some methods call for the use of many variations on the contest lifts, while others call for a more limited selection of exercises and an emphasis on mastering the contest lifts through repetition.[130] While many powerlifting routines invoke principles of sports science, such as specific adaptation to imposed demand (SAID principle),[131] there is some controversy around the scientific foundations of particular training methods, as exemplified by the debate over the merits of "speed work" using velocity based training or training to attain maximum acceleration of submaximal weights.[132] Powerlifting training differs from bodybuilding and weightlifting, with less focus on volume and hypertrophy than bodybuilding and less focus on power generation than weightlifting.[133][134]

Common set & rep schemes are based on a percentage of the lifter's 1RM (one rep maximum—meaning the most weight they are capable of lifting one time). For example, 5 sets of 5 reps (5x5) at 75% of the 1RM. Rest periods between sets range from 2–5 minutes based on the lifter's ability to recover fully for the next set.[135]

Recent advances in the accessibility of reliable and affordable technology has seen a rise in the popularity of velocity based training as a method to autoregulate daily training loads based on bar speed as a marker of readiness and neural fatigue status.[136] Research has shown this to be effective when used both generally or on an individualized basis,[137] and in some studies a superior programming methodology to percentage systems.[138][139]

Accessory movements are used to complement the competition lifts. Common accessory movements in powerlifting include bent over row,[140] lunges,[141] good mornings,[142] pull ups[143] and dips.[144]

Variable resistance training

editVariable resistance training relies upon adjusting resistance for stronger and weaker parts of a lift.[145] Any given movement has a strength phase sequence which involves moving through phases where a person is relatively stronger or weaker. This is commonly called a ‘strength curve’ which refers to the graphical representation of these phases.[146][c] These phases are based upon related anatomical factors such as joint angles, limb length, muscle engagement patterns, muscle strength ratios, etc.[148] Variable resistance training typically involves increasing resistance (usually weight) in the stronger phase and reducing it in the weaker phase.[149] The additional resistance can be added through the use of chains attached to the barbell for a squat in the bottom portion of the squat reduce the overall weight.[150] At the top portion of the squat, the chains are lifted from the floor to increase overall weight.[150] Bands can be used to increase resistance in a similar manner.[151] Alternatively, partial reps with heavier weights can be used in conjunction with full reps with lighter weights.[152] Training both phases accordingly through variable resistance techniques can allow the muscles to strengthen in accordance with a person’s natural strength curve.[153] It avoids a situation where, as a result of training, the weaker phase force potential is disproportionately great in regard to the stronger phase force potential.[153] These benefits can help a lifter to become more explosive and to complete a lift.[153]

Aerobic exercise

editIn addition to weight training, powerlifters may pursue other forms of training to improve their performance. Aerobic exercises may be used to improve endurance during drawn-out competitions and support recovery from weight training sessions.[154] This would be more noted as GPP training. The goal is to be well conditioned for more specific training.

Nutrition

editAll though powerlifting nutrition is subjective as there can be differences from person to person, there are general guidelines that athletes typically follow in order to perform optimally that can be applied to a strength sport setting. The primary concern of most diets is caloric intake as sufficient calories are needed to offset the energy expenditure of training allowing for adequate recovery from exercise. The International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends 40-70 kcals/kg/day for strength athletes who engage in 2-3 hours of intense training 5-6 days per week, compared to the 25–35 kcals/kg/day recommended for the average person engaging in a general fitness program, as regular training causes additional energy expenditure.[155] Additionally, when powerlifters are in the off season, it is recommended that athletes increase their caloric intake in order to meet the recommendations of the ISSN and optimize their training.[156] In addition to caloric intake, macronutrient intake plays a major role in the success of an athlete's diet. Protein, carbohydrates, and fats all play different roles in the performance and recovery process.[155] Optimizing protein intake enables a powerlifter to build more muscle and recover properly from intense training sessions.[155] The Journal of Sports Sciences recommends that strength athletes consume 1.6g–1.7g protein/kg/day in servings of 20 grams, 5 to 6 times a day for maximal muscle growth.[157] Sufficient carbohydrate intake allows an athlete to have adequate energy during training and restore any glycogen that is lost throughout their respect exercise.[155] However, it may not be as crucial for powerlifters as it for endurance athletes like runners due to the nature of the sport. For strength athletes, it is recommended to ingest a range of 4g to 7g carbohydrate/kg/day depending on the stage of training. Timing carbohydrate intake around training sessions may benefit powerlifters by giving them more energy throughout their workout.[157] Moreover, fats may help a strength athlete who is struggling to stay energized by providing more energy density, however, there is unclear evidence on the necessity of fats in a powerlifter's diet.[157] In addition to nutrition from foods, it is very common for powerlifters to take supplements in their diets. Caffeine and creatine mono-hydrate are two of the most research and common supplements among strength athletes as are proven to have benefits for training and recovery.[157]

Federations

editProminent international federations include:

- 100% Raw Powerlifting Federation

- International Powerlifting Federation (IPF)

- Natural Athlete Strength Association (NASA)

- Revolution Powerlifting Syndicate (RPS)

- USA Powerlifting (USAPL)

- World Drug-Free Powerlifting Federation (WDFPF)

- World Powerlifting Alliance (WPA)

- World Powerlifting Congress (WPC)

- Southern Powerlifting Federation (SPF)

- Global Powerlifting Committee (GPC)

- Canadian Powerlifting Union (CPU)

Of these federations, the oldest and most prominent is the IPF, which comprises federations from over 100 countries located on six continents.[158]

The IPF is the federation responsible for coordinating participation in the World Games, an international event affiliated with the International Olympic Committee.[159] The IPF has many international affiliates.[160]

Different federations have different rules and different interpretations of these rules, leading to a myriad of variations.[161] Differences arise on the equipment eligible, clothing, drug testing and aspects of allowable technique.[162]

Further, the IPF has suspended entire member nations' federations, including the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Iran, India and Uzbekistan, for repeated violations of the IPF's anti-doping policies.[163]

In January 2019, USA Powerlifting (at the time, an affiliate of the IPF) updated their policy to exclude transgender participation, in accordance with IOC guidelines.[164]

On March 1, 2022, the IPF announced that Russia and Belarus has been temporarily banned from competition due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the president of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, supporting Russia's invasion.[165]

Rank and classification

editThere are several classifications in powerlifting determining rank. These typically include Elite, Master, Class I, II, III, IV. The Elite standard is considered to be within the top 1% of competing powerlifters.[166] Several standards exist, including the United States Powerlifting Association classifications,[166] the IPF/Powerlifting America, USAPL (single-ply) classifications,[167] the APF (multi-ply) classifications,[168] and the Anti-Drug Athletes United (ADAU, raw) classifications.[169]

The Master classification should not be confused with the Master age division, which refers to athletes who are at least 40 years old.[170]

See also

edit- List of world championships medalists in powerlifting (men)

- List of world championships medalists in powerlifting (women)

- World Drug-Free Powerlifting Federation

- Paralympic powerlifting

- Powerlifting USA

- Power training

- Strongman (strength athlete)

- U.S. intercollegiate powerlifting champions

- Weight training

- Progression of the bench press world record

- History of physical training and fitness

- List of powerlifters

- Weightlifting

- Strength athletics

Notes

edit- ^ Depth rules are dependent on the federation. The IPF requires that lifters bend the knees and lower the body until the surface of the legs at the hip joint is lower than the tops of the knees.[118] Other federations allow the hip joint to be parallel with the knee joint.[119]

- ^ 'Supporting' is defined as a body position adopted by the lifter that could not be maintained without the counterbalance of the weight being lifted.[129]

- ^ A movement may be considered as having any number of strength phases but usually is considered as having two main phases: a stronger and a weaker. When the movement becomes stronger during the exercise, this is called an ascending strength curve. And when it becomes weaker this is called a descending strength curve. Some exercises involve a different pattern of strong-weak-strong. This is called a bell shaped strength curve.[147]

References

edit- ^ "The Choice for Drug-free Strength Sport : USAPL Raw/Unequipped Standards". USA Powerlifting. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Paciorek, Michael J.; Jones, Jefferey A. (2001). Disability sport and recreation resources. Cooper publishing group. ISBN 9781884125751.

- ^ Clayworth, Peter (5 September 2013). "Story: Bodybuilding, weightlifting and powerlifting". Te Ara.

- ^ "The History of Powerlifting". squat | press | lift | repeat. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Unitt, Dennis (4 April 2019). "The History of the International Powerlifting Federation". Powerlifting.Sport.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dunn, Will Freeman (10 January 2018). "The History of Powerlifting". Taylor's Strength Training. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "The History of Powerlifting in the USA". grindergym.com. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "A Brief History of the '50s & '60s | Two Decades That Launched Modern Bodybuilding". Muscular Development. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "Remembering Grimek" (PDF). Starkcenter: 2. April 1999.

- ^ a b "History - International Powerlifting Federation IPF". www.powerlifting.sport. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "History – BCPA Powerlifting". Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b "AAU World Powerlifting Championships". AllPowerlifting. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "AAU World Powerlifting Championships 1972 (results)". En.allpowerlifting.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ "1972 AAU Men's World Powerlifting Championships". Open Powerlifting. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "History - International Powerlifting Federation IPF". www.powerlifting.sport. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "IPF World Men's Powerlifting Championship, 9-10.11.1973, Harrisburg / USA". www.powerlifting.sport. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "IPF Men's World Powerlifting Championships". en.allpowerlifting.com. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "History - International Powerlifting Federation IPF". www.powerlifting.sport. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "EPF History - European Powerlifting Federation EPF". europowerlifting. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "First U.S. Power Lift For Women". The New York Times. 17 April 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "Jimmy Carter: "Amateur Sports Act of 1978 Statement on Signing S. 2727 Into Law. ," November 8, 1978". The American Presidency Project. University of California - Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "USPF the Legend". USPF the Legend. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ a b Thomas M. Hunt; Jan Todd. "Powerlifting's Watershed : frantz v. united states Powerlifting federation: The legal case that changed the nature of a sport" (PDF). Library.la84.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Terry Todd (22 October 1984). "Unlike all too many powerlifters, nine-time world champ". Sports Illustrated Vault. Archived from the original on 9 November 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Powerlifting at the Paralympics". www.topendsports.com. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "Para Sport 101: Everything You Need To Know About Paralympic Powerlifting". USA Paralympics Powerlifting. 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "American Strength Legends: The Organizers". American Strength Legends. 5 July 1998. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "United States Powerlifting Association Technical Rules 2023" (PDF). USPA: 10. 1 January 2023.

- ^ "HOME". APA Powerlifting. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "The Choice for Drug-free Strength Sport". USA Powerlifting. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "ADAU Merges With 100% Raw". Powerlifting Watch. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Message from Gene Rychlak 08.20.11". YouTube. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Raw Unity Powerlifting Championships - RAW Unity FAQ". Rawunitymeet.com. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Everything You Wanted to Know About Bench Shirts". Musclemagfitness.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "USA Powerlifting Online Newsletter". Usapowerlifting.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Origins of the Monolift". Powerlifting Watch. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 7. 23 January 2024.

- ^ "WRPF Technical Rules Book" (PDF). World Raw Powerlifting Federation: 11. 7 January 2023.

- ^ "New To Powerlifting - Let's Get Started". Deepsquatter.com. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "USA Powerlifting Online Newsletter". Usapowerlifting.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Some NASA Members Give Their Take on Lifting in the USAPL". Powerlifting Watch. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Southern Powerlifting Federation". Southernpowerlifting.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Exercise Face-Off: Traditional Deadlift vs. Sumo Deadlift | Men's Fitness". Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "International Powerlifting Federation Unveils Bench Press Rule Change for 2023". Barbend. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ a b Maile, LJ. "Use of fitness drug in Powerlifting". Powerlines.

- ^ Krawczyk, Bryce (11 July 2017). "So You Wanna Be a Powerlifter? Know Your Equipment". BarBend. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Putsov, Sergii (12 January 2024). "Can You Use Straps In Powerlifting? Rules Explained". Warm Body Cold Mind. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Is Using A Lifting Belt Cheating? No, Here's Why". GYMREAPERS. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Levin, Josh (9 August 2004). "One Giant Lift for Mankind". Slate.

- ^ "Raw Powerlifting vs Equipped Powerlifting". Vitruve. 24 November 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "The Place of Monolift Attachments in Modern Strength Training". AlphaFit. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Power Cage Vs Monolift Vs Combo Rack Differences, Powered By Ghost Strong Equipment | BarBend". 11 January 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Zai, Claire (8 March 2024). "How-To Squat Correctly: Technique, Benefits & Muscles Worked". Barbell Medicine. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Groves, Barney (2000). Power Lifting: Technique and training for athletic muscular development. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. ISBN 0-88011-978-0.

- ^ "Get better grip during bench press". Nordic Training Gear. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b Perrine, Stephen (29 October 2004). "Misfits of Muscle". Men's Health.

- ^ a b c Garland, Tony. "The Evolution of the Squat Suit Over the Past Twenty Years". EliteFTS. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Blatnik, JA; Skinner JW; McBride JM (December 2012). "Effect of supportive equipment on force, velocity, and power in the squat". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 26 (12): 3204–8. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182736641. PMID 22996018. S2CID 34123507.

- ^ a b McCullough, Tom. "The Power Squat". Strength Online.

- ^ Williams, Ryan (2004). "Effects of the Bench Shirt on Selected Bench Press Mechanics". 22 International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports (2004).

- ^ McKown, Mark (2007). Complete Body Development with Dumbbells. Meyer & Meyer Sport. p. 37.

- ^ Powerlifting, Anderson (23 August 2022). "A Beginner's Guide To Powerlifting Squat Suits". Anderson Powerlifting. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Thevenot, Cole (20 August 2019). "So You Want to Try A Bench Shirt…". Blacksmith Fitness. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Simmons, Louie. "THE BENCH PRESS SHIRT". Westside Barbell. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "100% Raw Powerlifting Federation". Powerlifting Watch. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "UPA Finalizes Definition of Raw". Powerlifting Watch. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "2008 Raw Nationals - USA Powerlifting". Usaplnationals.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "IPF Classic "unequipped" World Cup 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Marty Gallagher. "Is Powerlifting Undergoing a Resurrection?" (PDF). Startingstrength.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Machek, Steven B.; Cardaci, Thomas D.; Wilburn, Dylan T.; Cholewinski, Mitchell C.; Latt, Scarlett Lin; Harris, Dillon R.; Willoughby, Darryn S. (1 February 2021). "Neoprene Knee Sleeves of Varying Tightness Augment Barbell Squat One Repetition Maximum Performance Without Improving Other Indices of Muscular Strength, Power, or Endurance". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 35 (Suppl 1): S6–S15. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003869. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 33201154.

- ^ Pilon, Roc. "How To Put On Knee Sleeves Properly (According To Expert)". GYMREAPERS. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "Powerlifting Knee Sleeves". PowerliftingToWin. 5 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "What is the point of equipped powerlifting? - SoCal Powerlifting". SoCal Powerlifting. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "What are Squat Suits and Bench Shirts?". YPSI (in German). 16 September 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "The Power of Performance: Why Do You Wear a Squat Suit? Unveiling the Secrets to Enhanced Powerlifting". Virus Europe. 6 December 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Silverberg, Avi (18 November 2020). "Squat Suit: What Is It? How It Works? How to Use? Sizing?". PowerliftingTechnique.com. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "The Evolution of the Squat Suit Over the Past Twenty Years". Elitefts.com. 17 March 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ "Multi-Ply Powerlifting". grindergym.com. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "USA Powerlifting Raw With Wraps Division" (PDF). USA Powerlifting. 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Knee Sleeves vs Knee Wraps: Differences and Which Do You Need?". GYMREAPERS. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Sudnykovych, Jaysen (14 July 2023). "Wrist Wraps vs. Lifting Straps | What's the Difference?". TuffWraps.com. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Ehtesham, Mussayab (27 May 2024). "A Detailed Guide on How to Use Knee Wraps for Powerlifting". DMoose. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Lake, Jason P.; Carden, Patrick J. C.; Shorter, Kath A. (26 October 2012). "Wearing knee wraps affects mechanical output and performance characteristics of back squat exercise". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 26 (10): 2844–2849. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182429840. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 22995993.

- ^ "What are Squat Suits and Bench Shirts?". YPSI. 16 September 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Multi-Ply Powerlifting". Grinder Gym. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Silver, Tobin; Fortenbaugh, Dave; Williams, Ryan (23 July 2009). "Effects of the bench shirt on sagittal bar path". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 23 (4): 1125–1128. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181918949. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 19528864.

- ^ Canada, W. P. C. (15 June 2020). "BENCH SHIRT BASICS". WPC Canada. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "Raw vs Equipped Powerlifting". Iron Bull Strength - USA. 17 November 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "USA Powerlifting Technical Rules 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Welcome uspla.org - BlueHost.com" (PDF). Uspla.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Southern Powerlifting Federation". southernpowerlifting.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "IPF Technical Rules Book 2011" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation. January 2011.

- ^ "IPF Technical Rule Changes" (PDF).

- ^ "Powerlifting Weight Classes (Infographic)". 26 April 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "IPF Technical Rules Book 2023" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 3–4. January 2023.

- ^ a b "United States Powerlifting Association Technical Rules" (PDF). United States Powerlifting Association: 8. 1 January 2022.

- ^ IPF "IPF Technical Rules Book 2007" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation. March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007. (523 KB) (PDF), p. 3. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ Kay, Jonathan (2 February 2023). "Gender, Sex, and Powerlifting". Quillette. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Stone, Chris; Miller, Tom (3 July 2020). "Understanding Powerlifting Weight Classes". Fitness Volt. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "What Is a Good IPF GL Score for Powerlifters?". Sportive Tricks.

- ^ "APF BEST LIFTER FORMULA". World Powerlifting Congress. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Dunn, Will Freeman (6 May 2018). "Powerlifting Formulas – Is Wilks Best, and What Are the Alternatives?". Taylor's Strength Training. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Bodovni koeficijenti" (in Croatian). Go Max. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "SCHWARTZ & MALONE FORMULA" (PDF). Bellarmine University Intramural Sports: 1. June 2009.

- ^ "Infographic: The Greatest Wilks Scores of All Time (2024)". BarBend. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Age Coefficients Used In USA Powerlifting" (PDF). USA Powerlifting Minnesota: 1.

- ^ sannong (13 February 2015). "How is the "Best Lifter" determined in a meet?". World Powerlifting Congress. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Beginner's Guide to Powerlifting - Lifts, Competitions, Judges". ISSA Online. 7 April 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Halse, Henry (8 July 2011). "What Is Pull/Push Powerlifting?". SportsRec. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Goggins, Steve (16 February 2018). "WATCH: How Would You Program for a Deadlift Only Meet?". Elite FTS. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Naspinski, Gabriel (5 February 2015). "Programming Considerations for Bench-Only Competitors". Elite FTS. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Navraez, Israel Thomas. "Powerlifting Federations". Powerlifting to Win.

- ^ Padilla, Sebastian. "High bar vs Low bar Squats". SoCal Powerlifting. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 20. 23 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 12. 23 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 11. 23 January 2024.

- ^ "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 10. 23 January 2024.

- ^ "USPA Rulebook March 13th, 2024" (PDF). United States Powerlifting Association: 26 & 27. 13 March 2024.

- ^ Jacques, Heather (1 November 2022). "Powerlifting Rules & Commands for Squat, Bench & Deadlift". Lift Vault. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Padilla, Sebastian. "Possible Reasons for Red Lights in Powerlifting". SoCal Powerlifting. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 21. 23 January 2024.

- ^ "WPC Official Rule Book 2016 Edition" (PDF). World Powerlifting Congress: 8.

- ^ "Move United Para Powerlifting Rulebook 2023" (PDF). Move United: 6.

- ^ a b c "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation: 10. 23 January 2024.

- ^ Scantalides, Artemis (20 June 2017). "How To Choose Your Deadlift Stance". Aligned & Empowered Coaching. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "A Guide Powerlifting Deadlift Rules". Gunsmith Fitness. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "IPF Technical Rules Book 2024" (PDF). International Powerlifting Federation. 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Hitching the Deadlift | Mark Rippetoe". Starting Strength. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Training Specificity for Powerlifters". Marylandpowerlifting.com. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "The Seven Principles and You". powerliftingwatch.com.

- ^ "You are being redirected..." Jtsstrength.com. 25 March 2013.

- ^ Chiu, Loren (2007). "Powerlifting Versus Weightlifting for Athletic Performance". Strength and Conditioning Journal. 29 (5): 55–57. doi:10.1519/00126548-200710000-00008.

- ^ Schoenfeld, Brad J.; Ratamess, Nicholas A.; Peterson, Mark D.; Contreras, Bret; Sonmez, G. T.; Alvar, Brent A. (October 2014). "Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 28 (10): 2909–2918. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 24714538. S2CID 619257.

- ^ Thibaudeau, Christian (16 June 2014). "22 Proven Rep Schemes". T-nation.com. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ Nevin, Jonpaul (August 2019). "Autoregulated Resistance Training: Does Velocity-Based Training Represent the Future?". Strength & Conditioning Journal. 41 (4): 34–39. doi:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000471. ISSN 1524-1602. S2CID 86816034.

- ^ Dorrell, Harry F.; Moore, Joseph M.; Gee, Thomas I. (9 June 2020). "Comparison of individual and group-based load-velocity profiling as a means to dictate training load over a 6-week strength and power intervention". Journal of Sports Sciences. 38 (17): 2013–2020. doi:10.1080/02640414.2020.1767338. ISSN 0264-0414. PMID 32516094. S2CID 219561461.

- ^ Orange, Samuel T.; Metcalfe, James W.; Robinson, Ashley; Applegarth, Mark J.; Liefeith, Andreas (1 April 2020). "Effects of In-Season Velocity- Versus Percentage-Based Training in Academy Rugby League Players". International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 15 (4): 554–561. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2019-0058. ISSN 1555-0265. PMID 31672928. S2CID 202250276.

- ^ Canino, Maria (2015). Analysis of Heart Rate Training Responses in Division I Collegiate Athletes (Thesis). Illinois State University. doi:10.30707/etd2015.canino.m.

- ^ Dewar, Mike (25 May 2022). "Use the Bent-Over Row to Make Big Gains With Big Weights". BarBend. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Lee, Jihoo; Kim, Jisu (26 December 2022). "Effects of an 8-week lunge exercise on an unstable support surface on lower-extremity muscle function and balance in middle-aged women". Physical Activity and Nutrition. 26 (4): 14–21. doi:10.20463/pan.2022.0020. ISSN 2733-7545. PMC 9925109. PMID 36775647.

- ^ Antonio Cortes, Alexander Juan (21 January 2013). "Good Mornings: Understanding a Great Exercise". Elite FTS. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Pull Up Exercises for Powerlifting: What You Need to Know". MAGMA Fitness. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Will Dips Make You Stronger at Bench Press". Fringe Sport. 21 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Arazi, Hamid; Khoshnoud, Amin; Asadi, Abbas; Tufano, James J. (12 April 2021). "The effect of resistance training set configuration on strength and muscular performance adaptations in male powerlifters". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 7844. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.7844A. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87372-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8041766. PMID 33846516.

- ^ Lingenfelser, Ryan (22 July 2014). "Understanding Strength Curves". RDLFITNESS. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Lingenfelser, Ryan (22 July 2014). "Understanding Strength Curves". RDLFITNESS. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Trezise, J.; Blazevich, A. J. (6 August 2019). "Anatomical and Neuromuscular Determinants of Strength Change in Previously Untrained Men Following Heavy Strength Training". Frontiers in Physiology. 10: 1001. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01001. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 6691166. PMID 31447693.

- ^ Silvester, L Jay (1992). Weight Training for Strength and Fitness. London: Jones and Bartlett. pp. 23–25. ISBN 0867201398.

- ^ a b Jiang, Dongting; Xu, Gang (29 August 2022). "Effects of chains squat training with different chain load ratio on the explosive strength of young basketball players' lower limbs". Frontiers in Physiology. 13. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.979367. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 9465379. PMID 36105293.

- ^ Andersen, Vidar; Fimland, Marius S.; Kolnes, Maria K.; Saeterbakken, Atle H. (29 October 2015). "Elastic Bands in Combination With Free Weights in Strength Training: Neuromuscular Effects". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 29 (10): 2932–2940. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000950. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 25807031.

- ^ Dieter, Brad. "Are Partial Reps A Waste of Time?". NASM. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Conalton, Bobby (15 May 2013). "Benefits of Lifting Chains". elitefts. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Do Powerlifters Need Cardio?". EliteFTS. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d Kerksick, Chad M.; Wilborn, Colin D.; Roberts, Michael D.; Smith-Ryan, Abbie; Kleiner, Susan M.; Jäger, Ralf; Collins, Rick; Cooke, Mathew; Davis, Jaci N.; Galvan, Elfego; Greenwood, Mike; Lowery, Lonnie M.; Wildman, Robert; Antonio, Jose; Kreider, Richard B. (1 August 2018). "ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 15 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y. ISSN 1550-2783. PMC 6090881. PMID 30068354.

- ^ Oliver, Jonathan M; Mardock, Michelle A; Biehl, Adam J; Riechman, Steven E (15 September 2010). "Macronutrient intake in Collegiate powerlifters participating in off season training". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 7 (sup1): P8. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-7-S1-P8. PMC 2951052.

- ^ a b c d Slater, Gary; Phillips, Stuart M. (1 January 2011). "Nutrition guidelines for strength sports: Sprinting, weightlifting, throwing events, and bodybuilding". Journal of Sports Sciences. 29 (sup1): S67–S77. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.574722. ISSN 0264-0414. PMID 21660839. S2CID 8141005.

- ^ "Disciplines - International Powerlifting Federation IPF". www.powerlifting.sport. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Whiteley, Jo (3 July 2023). "Raw Powerlifting Will Debut at the 2025 World Games". BarBend. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Regions". International Powerlifting Federation. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Choosing A Powerlifting Federation". Fitness Volt. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Krawczyk, Bryce (11 July 2017). "So You Wanna Be a Powerlifter? Know Your Equipment". BarBend. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Suspension of the Russian and Ukrainian Federation" (PDF). IPF.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "Transgender Participation Policy | USA Powerlifting". Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "War in Ukraine". www.powerlifting.sport. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ a b Henriques, Tim (1 July 2024). "Lifter Classification Information". All About powerlifting. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "USA Powerlifting - the Choice for Drug-free Strength Sport : USAPL/IPF Lifter Classification Standards". Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "American Powerlifting Federation". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Powerlifting Equipped and Unequipped Elite Classification Charts". criticalbench.com.

- ^ "Technical Rule Book 2013" (PDF). www.powerlifting.sport. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.