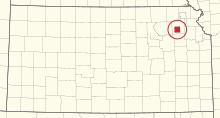

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (Potawatomi: Mshkodéniwek,[2] formerly the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians) is a federally recognized tribe of Neshnabé (Potawatomi people), headquartered near Mayetta, Kansas.

Mshkodéniwek | |

|---|---|

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Flag | |

| Total population | |

| 4,617[1] (2018) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Kansas) | |

| Languages | |

| Potawatomi, English |

History

editThe Mshkodésik ("People of the Small Prairie") division of the Potawatomi were originally located around the southern portions of Lake Michigan, in what today is southern Wisconsin, northern Illinois and northwestern Indiana. Due to their name in the Potawatomi language, the Mshkodésik were often confused with another tribe, the Mascoutens. As part of the Council of Three Fires, the Prairie Band were signatories to the 1829 Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien (7 Stat. 320). Independently of the Council of Three Fires, the Prairie Band were also signatories to the 1832 Treaty of Tippecanoe (7 Stat. 378) as the Potawatomi Tribe of Indians of the Prairie.

In the 1830s, Chief Shab-eh-nay, the leader of tribal residents on 1,300 acres (530 ha) of land in Illinois, went to visit members of his family who had been forced west to Kansas. While he was gone, the United States seized the property and auctioned it off to others.[3] Under the Indian Removal Act, the Prairie Band were forcibly relocated west, first to Missouri's Platte County in the mid-1830s and then to the vicinity of Council Bluffs, Iowa, in the 1840s, where they were known as the Bluff Indians. The tribe controlled up to five million acres (20,000 km2) at both locations. After 1846, the tribe moved to present-day Kansas. At that time, the reservation was thirty square miles which included part of present-day Topeka.

During the period from the 1940s - 1960s, in which the Indian termination policy was enforced, four Kansas tribes, including the Potawatomi, were targeted for termination. One of the first pieces of legislation enacted during this period was the Kansas Act of 1940 which transferred all jurisdiction for crimes committed on or against Indians from federal jurisdiction to the state of Kansas. It did not preclude the federal government from trying native people, but it allowed the state into an area of law in which had historically belonged only to the federal government.[4]

On August 1, 1953, the US Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108 which called for the immediate termination of the Flathead, Klamath, Menominee, Potawatomi, and Turtle Mountain Chippewa, as well as all tribes in the states of California, New York, Florida, and Texas. Termination of a tribe meant the immediate withdrawal of all federal aid, services, and protection, as well as the end of reservations.[5] A memo issued by the Department of the Interior on January 21, 1954, clarified that the reference to "Potawatomi" in the Resolution meant the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation, the Kickapoo, the Sac and Fox and the Iowa tribes in Kansas.[6]

Because jurisdiction over criminal matters had already been transferred to the state of Kansas by the passage of the Kansas Act of 1940, the government targeted the four tribes in Kansas for immediate termination.[6] In February 1954, joint hearings for the Kansas tribes were held by the House and Senate Subcommittees on Indian Affairs.[7]

The Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation tribal leader, Minnie Evans (Indian name: Ke-what-no-quah Wish-Ken-O)[8] led the effort to stop termination.[9] Tribal members sent petitions of protest to the government and multiple delegations went to testify at congressional meetings in Washington, DC.[10] Tribal Council members Vestana Cadue, Oliver Kahbeah, and Ralph Simon of the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas traveled at their own expense to testify as well. The strong opposition from the Potawatomi and Kickapoo tribes helped them, as well as the Sac & Fox and the Iowa Tribe, avoid termination.[11]

In May 1997, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation broke ground on the construction of the Prairie Band Casino & Resort to generate revenue for the tribe. The establishment opened on January 12, 1998, under the management of Harrah's Entertainment (an outside commercial entity). Tribal management subsequently assumed control of the establishment in July 2007.[12]

The tribe purchased a corner of the original reservation in DeKalb County, Illinois in 2006 and leased the land for farming.[13] The United States Department of the Interior formally placed the 130 acres (53 ha) into trust for the benefit of the tribal band in 2024, thereby giving the Prairie Band tribal sovereignty over the land. The Prairie Band Potawatomi became the first and only federally recognized tribal nation in Illinois, since Native Americans were dispossessed in the 19th century.[3]

Government

editThe Prairie Band are governed by a democratically elected tribal council.[14]

Notable people

edit- Charles J. Chaput, first Native American archbishop[15]

- Venida Chenault, president of Haskell Indian Nations University[16]

- Curtis J. Keltner, Green Beret, Iraq War veteran

- Jessica Rickert, the first female American Indian dentist in America, which she became upon graduating from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry in 1975. She was a direct descendant of the Indian chief Wahbememe (Whitepigeon).[17]

- Shabbona, 19th-century warrior and chief in Illinois

- Stephanie "Pyet" DeSpain, winner of Season 1 of the television cooking competition Next Level Chef

References

edit- ^ "Letter from Liana Onnen, Chairwoman of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians to Tara Sweeney, Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, June 30, 2018" (PDF). Bureau of Indian Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ "Potawatomi - English Dictionary, "Mshkodéni", in plural form". Archived from the original on March 21, 2024. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Miller, Violet (April 20, 2024). "Prairie Band Potawatomi becomes first federally recognized tribal nation in Illinois". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Francis, John J., Stacy L. Leeds, Aliza Organick, & Jelani Jefferson Exum. "Reassessing Concurrent Tribal–State–Federal Criminal Jurisdiction in Kansas" (PDF). Kansas Law Review. 59: 967. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ US Statutes at Large 67:B132

- ^ a b "Data" (PDF). www.bia.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Davis, Mary B. (1996). Native America in the Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia (book). Routledge. pp. 286–287. ISBN 9781135638542. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Info". genealogytrails.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ "Potawatomi Historical Timeline". Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ "Tribal History » Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation". www.pbpindiantribe.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ Davis: Native America (1996), pp. 286–287

- ^ Mitchell, Gary. "Timeline". Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Archived from the original on April 7, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ O’Connor, John (June 23, 2024). "Illinois may soon return land the US stole from a Prairie Band Potawatomi chief 175 years ago". AP News. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Past Tribal Councils | Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation". Archived from the original on December 6, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ Cavanaugh, R. (November 23, 2017). "The resilience of Native American Catholicism". The Catholic World Reporter. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ "BIE Director Dr. Charles Roessel Announces Dr. Venida S. Chenault as Haskell President | Indian Affairs". www.bia.gov. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2023. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Jessica Rickert - Michigan Women Forward". Miwf.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.