This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

Prehistoric archaeology is a subfield of archaeology,[1] which deals specifically with artefacts, civilisations and other materials from societies that existed before any form of writing system or historical record. Often the field focuses on ages such as the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age, although it also encompasses periods such as the Neolithic. The study of prehistoric archaeology reflects the cultural concerns of modern society by showing interpretations of time between economic growth and political stability.[2] It is related to other disciplines such as geology, biology, anthropology, historiography and palaeontology, although there are noticeable differences between the subjects they all broadly study to understand; the past, either organic or inorganic or the lives of humans.[2] Prehistoric archaeology is also sometimes termed as anthropological archaeology because of its indirect traces with complex patterns.[2]

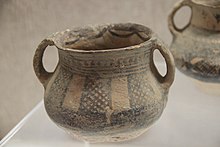

Due to the unique nature of prehistoric archaeology, in that written records can not be drawn upon to aid the study of the societies it focuses on, the subject matter investigated is entirely material remains as they are the only traceable evidence that is available. Material evidence includes pottery, burial goods, the remains of individuals and animals such as bones, jewellery and decorative items as well as many other artefacts. The subfield has existed since at least the late 1820s or early 1830s [3] and is now a fully recognised and separate field of archaeology. Other fields of archaeology include; Classical archaeology, Near Eastern archaeology - as known as Biblical archaeology, Historical archaeology, Underwater archaeology and many more, each working to reconstruct our understanding of everything from the ancient past right up until modern times. Unlike continent and area specific fields of archaeology such as; Classical - which studies specifically the Mediterranean region and the civilisations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome in antiquity, the field of prehistoric archaeology is not contained to one continent. As such, there are many excavations attributed to this field which have occurred and are occurring all over the world to uncover all different types of settlements and civilisations.

Without history to provide evidence for names, places and motivations, prehistoric archaeologists speak in terms of cultures which can only be given arbitrary modern names relating to the locations of known occupation sites or the artifacts used. It is naturally much easier to discuss societies rather than individuals as these past people are completely anonymous in the archaeological record. Such a lack of concrete information means that prehistoric archaeology is a contentious field and the arguments that range over it have done much to inform archaeological theory.[4]

Origins

editPrehistoric archaeology, as with many other fields of archaeology, is attributed to multiple different individuals therefore an accurate and definitive timeline for its creation is difficult to present. The origins of prehistoric archaeology were marked by treasure hunting also known as antiquarianism[5] and the individuals involved were not focused on scientific enquiry, as such the line between when the field moved from gathering artefacts to legitimate study is difficult to define. The first mention and use of the word prehistoric in archaeological terms was in the works of Daniel Wilson in 1851 within his book ‘The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland’,[6] another early instance of prehistoric being used archaeologically is within Paul Tournal’s work in 1833 where he uses préhistoire to describe his work in Bize-Minervois located in the south of France.[3] The phrase prehistoric archaeology did not officially become an English archaeological term until 1836,[7] and further, the common three-age system coined by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen which classifies European prehistoric chronology was also invented during this year.[8]

Beyond that, there are three other individuals who represented different field schools who are thought to have begun the first excavations dedicated solely to the study of prehistoric archaeology at roughly the same time between the 1820s to 1830s. Boucher de Perthes – a French archaeologist leading the Abbeville field school who uncovered handaxes in the Somme River,[9] Jens Jacob Worsaae – a Danish archaeologist leading the Copenhagen field school who studied stratified assemblages in Denmark,[10] and Giuseppe Scarabelli – an Italian archaeologist who led the Imola field school who studied stratigraphy in Italy.[11][12]

Outside of these individuals, each continent began to host excavations and field schools to explore their own prehistory across a wide spectrum of dates. Several examples, though not a complete list of every country, are listed below by continental area. Within Europe exploration began in England with several individuals such as amateur archaeologist William Pengelly who studied the Kent Cavern in approximately 1846,[13] and within Turkey excavation into specifically prehistoric archaeological sites did not begin until much later between the 1980s to the 1990s into the region of Anatolia.[14] In Asia and Australasia, prehistoric archaeology began in China in the 1920s with the work of amateur Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson who uncovered Homo erectus fossils in the Zhoukoudian cave in southwest Beijing and excavated Yangshao in Henan,[15] in India excavation began with the works of Captain H. Congreve in 1847,[16] in Japan prehistoric archaeology as it is defined by European standards began with the works of German collector Heinrich von Siebold in 1869 – though there had been an internal interest in prehistoric archaeology since the 1700s,[17] in Vietnam excavation began in 1960 [18] and in Australia the discipline of archaeology was solidified in the 1960s and 70s which allowed it to begin to expand and include Indigenous peoples and their heritage.[19] In North America exploration began in the United States in the mid-1800s with the collective excavation interests being led by the works of the American Philosophical Society, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Smithsonian Institution[20] and in Canada excavations started in 1935 though it was not until 1965 that it fully took off as an important field of archaeology.[21] In South America within Argentina excavations began between 1880 and 1910.[22] In Africa investigations into prehistoric civilisations began in roughly the 1960s and 70s [23] and further prehistoric archaeology began explorations into the Middle East in areas such as Iran in 1884 with excavations by the French at Susa.[24]

Purpose

editThe purpose of prehistoric archaeology is to explore and understand civilisations that existed before writing systems; including the Stone, Bronze and Iron Age societies across the world. Within its early origins prehistoric archaeology had a focus on gathering artefacts and treasures to display in museums and private collections often to bring wealth back for the individual. Later on the field allowed for the more legitimate study of material evidence and data in order to ascertain important details such as; when the site may have been occupied, who was living there, what activities they may have engaged in, and finally what happened to them to either cause them to leave or make the area uninhabitable.

Notable Archaeologists

editThere are multitudes of credible past and emerging prehistoric archaeologists who have dedicated time and effort into honing their craft in order to accurately understand the lives of the individuals and societies they are studying. Some of the important foundational archaeologists are; Daniel Wilson – a Scottish-born Canadian archaeologist who first brought the term prehistoric into an archaeological context, Paul Tournal – a French amateur archaeologist, Christian Jürgensen Thomsen – a Danish antiquarian who classified the three age system important to aiding early European archaeological works,[8] Boucher de Perthes – a French archaeologist who uncovered handaxes in the Somme River,[9] Jens Jacob Worsaae – a Danish archaeologist who studied stratified assemblages in Denmark,[10] Giuseppe Scarabelli – an Italian archaeologist who studied stratigraphy in Italy,[11][25] and William Pengelly – an English archaeologist.[13] They each fundamentally contributed to beginning the field of archaeology through defining how the subfield is different to archaeology.

More modern archaeologists, including Ali Umut Türkcan – who directed the excavations at Çatalhöyük as of 2022,[26] have helped to further these developments in the field by directing excavations and studying materials found within the sites. Other modern archaeologists include; Paul Bahn – a British archaeologist who studies prehistoric rock art, Richard Bradley – a British archaeologist who specialises in European prehistory and has a particular focus on Prehistoric Britain, E. C. L. During Caspers (also known as Elizabeth Christina Louisa During Caspers) – a Dutch archaeologist who studied prehistoric Mesopotamia, Ufuk Esin – a Turkish archaeologist who specialised in prehistoric Anatolia, Pere Bosch-Gimpera – a Spanish-born Mexican archaeologist who studied prehistoric Spain, Lynne Goldstein – an American specialising in prehistoric eastern North America, Jakob Heierli – a Swedish archaeologist who studied prehistoric Sweden, Louise Steel – a British archaeologist who focused on prehistoric Cyprus, and Joyce White – an American archaeologist who specialises in prehistoric Southeast Asia. There are many more individuals whose importance to the continuation of this field has not been stated or acknowledged here.

Main types and locations of sites

editSome of the main types of sites include early proto-city and proto city-states, settlements, temples and sanctuaries of worship and cave sites. To define each of these terms archaeologically; a proto city-state is a large town or village that existed in the Neolithic era, it is also categorised by its lack of central rule or deliberate city organisation of infrastructure.[27] A settlement is an area where individuals lived either permanently or semi-permanently, conversely temples or sanctuaries were areas of cult practice or worship to the gods or beings associated with the specific people,[27] areas of worship in early prehistoric sites or periods can also include spiritual areas of prominent religious importance without the presence of a directly associated deity.[27] Cave sites are sheltered areas, usually in rock formations where individual members of a society may have gathered together in either semi-permanent or permanent basis to create art, to dwell or to prepare food.[27] All prehistoric archaeology sites must contain evidence of humans – even if they did not actively live on the site or visited it occasionally, and a lack of historical record within the society. Sites that feature the ability of the inhabitants to record information about themselves are not considered prehistoric.

Prehistoric settlements are scattered all over the world, they vary in age and size. The period in which prehistoric archaeology covers is most often the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages, within each of these ages periods such as the Neolithic within the Stone age are explored deeply. In Western Europe the prehistoric period ends with Roman colonisation in 43 AD,[28][29] with some non-Romanised areas the period does not end until as late as the 5th Century AD. Although in many other places, notably Egypt (at the end of the Third Intermediate Period [30] ) it finishes much earlier and in others, such as Australia, much later. Some of the main sites that are being studied are; Çatalhöyük in Turkey, the Chauvet Cave in southern France, Bouldnor Cliff Mesolithic Village in the United Kingdom and Franchthi in Greece among many others. New sites are being uncovered regularly and their importance to understanding prehistoric peoples continues to further our knowledge of the past.

Methods of investigation and analysis

editArchaeologists use many different methods to research the artefacts and materials that may be found during an excavation. Within early excavations dedicated to treasure hunting little to no care was taken when removing soil covering artefacts or when removing the artefacts and materials themselves from sites which may have led to the destruction of materials and has placed some recovered artefacts at risk. Often the digs were conducted by amateurs and treasure hunters who did not have the knowledge we do now about how to remove artefacts safely. Some of the main techniques used to gently recover artefacts or to ensure the integrity of the site remains for future exploration and the preservation of the site are; aerial photography – to survey the site, stratigraphic measurements – which document the layers of soil to aid in site dating, fieldwalking - which involves walking the ground and looking for objects and making site plans to record the locations of objects and remains on a site.[31][27]

Within aerial photography several important markers of archaeological sites can be revealed such as; shadow marks, crop marks and soil marks.[27] Archaeologists also use a range of techniques when excavating a site to uncover materials including; digging test pits, creating trenches and using the box-grid or quadrant method to keep track of different areas of the site.[27]

Some of the technology used to assist in looking for and uncovering materials in prehistoric archaeological sites are; electrical resistivity meters – which help locate objects underground non-disruptively, laser theodolites – to help map the site layout, satellite survey - which uses satellites to get an aerial view of the site, lidar - which uses lasers to scan for objects underground and sonar - which uses soundwaves to scan the earth for objects.[32][27] None of these techniques are solely practised within prehistoric archaeology, most archaeological techniques may be used across many of the different subfields of archaeology.

Issues in the field

editThere are a vast amount of difficulties faced within prehistoric archaeology including; site degradation,[31] which makes understanding a site very difficult as it erases evidence that may have been useful for gaining insight into the civilisation. Degradation of a site may be exacerbated by climate change as often prehistoric sites are delicate due to the nature of their age, for example, material evidence such as textile fabric which may have survived from antiquity in rare contexts due to being buried may be lost due to the top layers of the site being uncovered. However, as cosmologist Martin Rees and astronomer Carl Sagan have said ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’ which is highly relevant within the field of prehistoric archaeology as often archaeologists must work with missing pieces and theorise in order to understand a site. Due to the substantial gaps that exist in the prehistoric record, there are many periods of time, inventions and materials – particularly those that were made out of perishable materials such as wood or textile fabrics, that have been lost to time or that are incredibly difficult to locate due to the conditions that must exist in order for them to survive. It is because of these gaps that in order to understand the physical evidence that has been recovered prehistoric archaeologists, as well as their counterparts in the sibling fields of archaeology, must make educated guesses as to what is there and what should be there based on the finds that they have. The variety of theories regarding the purpose of objects or sites for example obliges archaeologists to adopt a critical approach to all evidence and to examine their own constructs of the past. Structural functionalism and processualism are two schools of archaeological thought which have made a great contribution to prehistoric archaeology.[33][34]

Other issues within the field of prehistoric archaeology which also affect every other branch of archaeology is the ethics[35] of removing artefacts and or storing finds in museums. This moral question is a delicate balance within prehistoric archaeology as all finds and bodies must be treated with respect but archaeologists also wish to study them in order to further their understanding of the different origins of humanity.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Archaeology Defined". Institute for Field Research. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Fagan, Brian M. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195076189.001.0001. ISBN 9780199891085. OCLC 35178577.

- ^ a b Chippindale, Christopher (1988), "The Invention of Words for the Idea of 'Prehistory'", Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 54: 303–313, doi:10.1017/S0079497X00005867

- ^ Murray, Tim (17 June 2013). "Why the history of archaeology is essential to theoretical archaeology" (PDF). Complutum. 24 (2). Universidad Complutense de Madrid: 21–31. doi:10.5209/rev_CMPL.2013.v24.n2.43364. ISSN 1131-6993. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Nelson, N (January 22, 1937), "Prehistoric Archeology, Past, Present and Future", Science, 85 (2195): 81–98, Bibcode:1937Sci....85...81N, doi:10.1126/science.85.2195.81, PMID 17758391, S2CID 7812572

- ^ Wilson, Daniel (1851). The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland. The Library of Alexandra. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139481380. hdl:2027/bc.ark:/13960/t3cz6qg6t. ISBN 9781139481380.

- ^ Eddy, Matthew (2011), "The prehistoric mind as a historical artefact", The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, 65: 1–8

- ^ a b Heizer, Robert (1962), "The Background of Thomsen's Three-Age System", Technology and Culture, 3 (3): 259–266, doi:10.2307/3100819, JSTOR 3100819, S2CID 112422270

- ^ a b Sackett, James (2014), "Boucher de Perthes and the Discovery of Human Antiquity", Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 24: Art.2, doi:10.5334/bha.242

- ^ a b "Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae". Oxford Reference. 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Battista Vai, Gian (2019), "The Origin of Prehistoric Archaeology", Earth Sciences History, 38 (2): 327–356, Bibcode:2019ESHis..38..327V, doi:10.17704/1944-6178-38.2.327, S2CID 210276670

- ^ Guidi, Allesandro (2010). "The Historical Development of Italian Prehistoric Archaeology: A Brief Outline". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. 20 (2): 13. doi:10.5334/bha.20203.

- ^ a b McFarlane, Donald A.; Lundberg, Joyce (2005), "The 19th Century excavation of Kent's Cavern, England", Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, 67: 39–47

- ^ Gates, Marie-Henriette (April 1997), "Archaeology in Turkey", American Journal of Archaeology, 101 (2): 241–305, doi:10.2307/506511, hdl:11693/49557, JSTOR 506511, S2CID 245264809

- ^ Archaeology and the study of Ancient China, Asian Art Museum, retrieved 28 April 2022

- ^ Taylor, Meadows (1869), "On Prehistoric Archaeology of India", The Journal of the Ethnological Society of London (1869-1870), 1 (2): 157–181, doi:10.2307/3014449, JSTOR 3014449

- ^ Stein, Britta (2018). History of Archaeology in Japan. Smith C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer.

- ^ Boriskovsky, P (1866), "Basic Problems of the Prehistoric Archaeology of Vietnam", Asian Perspectives, 9: 83–85

- ^ Smith, Claire (2007). Digging it up in Down Under. World Archaeological Congress Cultural Heritage Manual Series. Springer.

- ^ "Public Archeology in the United States - A Timeline". Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Wright, J (April 1985), "The Development of Prehistory in Canada, 1935-1985", American Antiquity, 50 (2): 421–433, doi:10.2307/280499, JSTOR 280499, S2CID 163418336

- ^ Podgorny, Irina (2015), "Human Origins in the New World? Florentino Ameghino and the Emergence of Prehistoric Archaeology in the Americas (1875–1912)", PaleoAmerica, 1: 68–80, doi:10.1179/2055556314Z.0000000008, hdl:11336/49531, S2CID 128406453

- ^ Miller, Joseph C. (Autumn 1985), "History and Archaeology in Africa", The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 16 (2): 291–303, doi:10.2307/204180, JSTOR 204180

- ^ Potts, Daniel T. "The History of Archaeological Research in Iran: A Brief Survey". Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Guidi, Allesandro (2010). "The Historical Development of Italian Prehistoric Archaeology: A Brief Outline". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. 20 (2): 13. doi:10.5334/bha.20203.

- ^ Bilge, Kucukdogan. "Current excavations at Çatalhöyük". Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grant, Jim; Gorin, Sam; Fleming, Neil (31 March 2015). The Archaeology Coursebook: An Introduction to Themes, Sites, Methods and Skills. Routledge. ISBN 9780415526883.

- ^ "Roman England, the Roman in Britain 43 - 410 AD". Historic UK. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ Collis, John (September 2008). "The Earlier Iron Age in Britain and the Near Continent. Edited by Colin Haselgrove and Rachel Pope. 298mm. Pp 429, 145 ills and 19 tables. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2006. ISBN 9781842172537. £75 (hbk).The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond. Edited by Colin Haselgrove and Tom Moore. 298mm. Pp 529, 190 ills and 25 tables. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2006. ISBN 9781842172520. £90 (hbk)". The Antiquaries Journal. 88: 434–435. doi:10.1017/s0003581500001566. ISSN 0003-5815.

- ^ "Egypt in the Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1070–664 B.C.)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ a b Frost, Randell. "Excavation Methods". Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Frost, Randell. "Excavation Methods". Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (December 1968). "Major Concepts of Archaeology in Historical Perspective". Man. 3 (4). Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: 527–541. doi:10.2307/2798577. JSTOR 2798577.

- ^ Kushner, Gilbert (April 1970). "A Consideration of Some Processual Designs for Archaeology as Anthropology". American Antiquity. 35 (2). Cambridge University Press: 125–132. doi:10.2307/278141. JSTOR 278141. S2CID 147568983.

- ^ Alfredo, DGonzález-Ruibal (2018). "Ethics of Archaeology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 47: 345–360. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102317-045825. S2CID 149684996.