This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Nepal is a multi-ethnic, multiracial, multicultural, multi-religious, and multilingual country. The most spoken language is Nepali followed by several other ethnic languages.

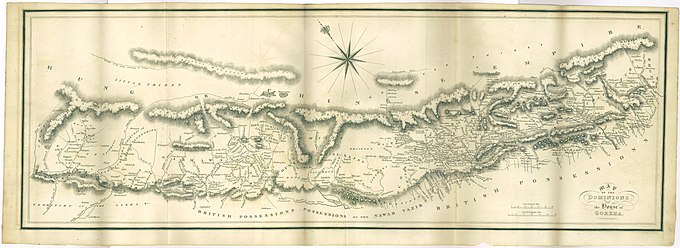

The modern day Kingdom of Nepal was established in 1768 and started a campaign of unifying what would form the modern territories of Nepal. Some former territories had been lost due to the Sino-Nepalese War. The conflict ended with both victories and losses with the kingdom ultimately accepting tributary status with the Qing dynasty of China from 1792 to 1865.[1] The Anglo-Nepalese War ended in British victory and resulted in the ceding some Nepalese territory in the Treaty of Sugauli. In a historical vote for the election of the constituent assembly, the Nepalese parliament voted to abolish the monarchy in June 2006. Nepal became a federal republic on 28 May 2008 and was formally renamed the 'Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal' ending the 200-year-old reign of the Shah monarchs.

Toponymy

editNepal's origin remains a mystery despite written records dating back to the fifth century A.D. Classical Indian sources mention Nepal, and Nepali stories delve into mythology, religion, and culture rather than providing a clear historical account.[2]

The derivation of the word Nepal is a subject of various theories:

- Most inhabitants of northern Nepal came from Tibet, where they herded sheep and produced wool. In Tibetan, ne means "wool" and pal means "house". Thus, Nepal is "house of wool".[3]

- Newar people in the Kathmandu valley named their homeland Nepal, derived from "Nepa," meaning "country of the middle zone," highlighting its central location in the Himalayas.[3]

- A popular theory is that Lepcha people associated Nepal with a "sacred or holy cave."[3]

- According to Hindu mythology, Nepal derives its name from an ancient Hindu sage called Ne, referred to variously as Ne Muni or Nemi.

- According to Buddhist legend, the deity Manjushri drained the water from Nagadaha (a mythical lake believed to have filled the Kathmandu Valley). The valley became habitable, ruled by Bhuktaman a cow-herder, who took advice from the sage named "Ne". Pāla means "protector" or "taking care", so Nepal reflected the name of the sage who took care of the place.[3][4]

Ancient history

editPrehistory

editPrehistoric sites of palaeolithic, mesolithic and neolithic origins have been discovered in the Siwalik hills of Dang district.[5] The earliest inhabitants of modern Nepal and adjoining areas are believed to be Tharus and Maithil people from the Mithila (region) in Madhesh Province and Terai districts of Koshi Province and Lumbini Province. It is possible that the Dravidian people whose history predates the onset of the Bronze Age in the Indian subcontinent (around 3300 BC) inhabited the area ruled by King Janaka before the arrival of other ethnic groups like the Tibeto-Burmans and Indo-Aryans from across the border.[6] Maithils, Indo-Aryans and Tharus, Tibeto-Burmans who mixed heavily with Indians in the southern regions, are natives of the central Madhesh Province and Terai region of Nepal.[7] The first documented tribes in Nepal are the Kirat people is the record of Kirat Kings from Kirata Kingdom from 800 BC, which shows Kirats were recorded in Nepal last 2000 to 2500 years, with an extensive dominion, possibly reaching at one time to the delta of the Ganges.[8] Other ethnic groups of Indo-Aryan origin later migrated to southern part of Nepal from Indo-Gangetic Plain of northern India.[9][10]

Stella Kramrisch ( 1964 ) mentions a substratum of a Maithili language speaking Maithils race of Pre - Indo-Aryans and Tharus of Dravidians race, who were in Nepal even before the Newars, who formed the majority of the ancient inhabitants of the valley of Kathmandu.[11]

Emperor Ashoka was responsible for the construction of several significant structures in Nepal. These include the Ramagrama Stupa, Gotihawa Pillar of Ashoka, Nigali-Sagar Ashoka Pillar inscription, and the Lumbini pillar inscription of Ashoka.The Chinese pilgrims Fa-Hien (337 CE – c. 422 CE) and Xuanzang (602–664 CE) describe the Kanakamuni Stupa and the Asoka Pillar of currently Nepal region in their travel accounts. Xuanzang speaks of a lion capital atop the pillar, now lost. A base of a Pillar of Ashoka has been discovered at Gotihawa, a few miles from Nigali Sagar, and it has been suggested that it is the original base of the Nigalar Sagar pillar fragments.[12] In 249 BCE, Emperor Asoka founded Lalitapatan city of Nepal.[13][14]

Legends and ancient times

editAlthough very little is known about the early history of Nepal, legends and documented references reach far back to the 30th century BC.[15] Also, the presence of historical sites such as the Valmiki ashram, indicates the presence of Sanatana (ancient) Hindu culture in parts of Nepal at that period.

According to legendary accounts, the early rulers of Nepal were the Gopālavaṃśi (Gopal Bansa) or "cowherd dynasty", who presumably ruled for about five centuries. They are said to have been followed by the Mahiṣapālavaṃśa or "buffalo-herder dynasty", established by a Yadav named Bhul Singh.[16]

The Shakya clan formed an independent oligarchic republican state known as the Śākya Gaṇarājya during the late Vedic period (c. 1000 – c. 500 BCE) and the later so-called second urbanisation period (c. 600 – c. 200 BCE).[17] Its capital was Kapilavastu, which may have been located in present-day Tilaurakot, Nepal.[18][19][20] Gautama Buddha (c. 6th to 4th centuries BCE), whose teachings became the foundation of Buddhism, was the best-known Shakya. He was known in his lifetime as "Siddhartha Gautama" and "Shakyamuni" (Sage of the Shakyas). He was the son of Śuddhodana, the elected leader of the Śākya Gaṇarājya.

Kirat dynasty

editThe context of Kirat Dynasty ruling in Nepal before Licchavi dynasty and after Mahispal (Ahir) dynasty are depicted in different manuscripts. Kirat dynasty was the longest ruling dynasty in Nepalese history, ruling from the 800 BC–300 AD for about 1,225 years. They ruled kathmandu valley before delineating the area between the Sun Koshi and Tama Koshi rivers as their native land, the list of Kirati kings is also given in the Gopal genealogy. The Mahisapala dynasty was a dynasty established by Abhira that ruled the Kathmandu Valley.[21][22][23] They took control of Nepal after replacing the Gopala dynasty.[24] Three kings of Mahisapala dynasty ruled the valley before they were overthrown by the Kirata dynasty.[25][26] They were also known as Mahispalbanshi.[27] By defeating the last king of the Avir dynasty Bhuwansingh in a battle, Kirati King Yalung or Yalamber had taken the regime of the valley under his control. In Hindu mythological perspective, this event is believed to have taken place in the final phase of Dvapara Yuga or initial phase of Kali Yuga or around the 6th century BC. Descriptions of 32, 28 and 29 Kirati kings are found according to the Gopal genealogy, language-genealogy and Wright genealogy respectively.[28] By means of the notices contained in the classics of the East and West, the Kiranti people were living in their present whereabouts for the last 2000 to 2500 years, with an extensive dominion, possibly reaching at one time to the delta of the Ganges.[8]

Under the Guptas

editDuring the time of the Gupta Empire, the Indian emperor Samudragupta recorded Nepal as a "frontier kingdom" which paid an annual tribute. This was recorded by Samudragupta's Allahabad Pillar inscription, which states the following in lines 22–23.

"Samudragupta, whose formidable rule was propitiated with the payment of all tributes, execution of orders and visits (to his court) for obeisance by such frontier rulers as those of Samataṭa, Ḍavāka, Kāmarūpa, Nēpāla, and Kartṛipura, and, by the Mālavas, Ārjunāyanas, Yaudhēyas, Mādrakas, Ābhīras, Prārjunas, Sanakānīkas, Kākas, Kharaparikas and other nations"

Licchavi dynasty

editThe kings of the Lichhavi dynasty (originally from Vaishali in modern-day India) ruled what is the Kathmandu valley in modern-day Nepal after the Kirats. It is mentioned in some genealogies and Puranas that the "Suryavansi Kshetriyas had established a new regime by defeating the Kirats". The Pashupati Purana mentions that "the masters of Vaishali established their own regime by confiding Kiratis with sweet words and defeating them in war". Similar contexts can be found in Himbatkhanda, which also mentions that "the masters of Vaishali had started ruling in Nepal by defeating Kirats". Different genealogies state different names of the last Kirati king. According to the Gopal genealogy, the Lichhavis established their rule in Nepal by defeating the last Kirati King 'Khigu', 'Galiz' according to the language-genealogy and 'Gasti' according to Wright genealogy.[28]

Medieval history

editThakuri dynasty

editAfter Aramudi, who is mentioned in the Kashmirian chronicle, the Rajatarangini of Kalhana (1150 CE), many Thakuri kings ruled over parts of the country up to the middle of the 12th century CE. Raghava Deva is said to have founded a ruling dynasty in 879 CE, when the Lichhavi rule came to an end. To commemorate this important event, Raghava Deva started the 'Nepal Era' which began on 20 October, 879 CE. After Amshuvarma, who ruled from 605 CE onward; the Thakuris had lost power and they could regain it only in 869 CE.[citation needed]

Gunakama Deva, who ruled from 949 to 994 CE, commissioned the construction of a big wooden shelter, built from the wood of a single tree, called Kasthamandapa. The name of the capital, 'Kathmandu', is derived from this. Gunakama Deva founded the town Kantipur (modern-day Kathmandu). The tradition of Indra Jatra started during his reign. Bhola Deva succeeded Gunakama Deva. The next ruler was Laxmikama Deva who ruled from 1024 to 1040 CE. He built the Laksmi Vihara and introduced the tradition of worshiping the Kumari; young prepubescent girls believed to be manifestations of the divine female energy or devi. He was succeeded by his son, Vijayakama Deva, who introduced the worship of the Naga and Vasuki. Vijaykama Deva was the last ruler of this dynasty. After his death, the Thakuri clan of Nuwakot occupied the throne of Nepal.

Bhaskara Deva, a Thakuri from Nuwakot, succeeded Vijayakama. He is said to have built Navabahal and Hemavarna Vihara. After Bhaskara Deva, four kings of this line ruled over the country. They were Bala Deva, Padma Deva, Nagarjuna Deva and Shankara Deva. Shankara Deva (1067–1080 CE) was the most illustrious ruler of this dynasty. He established the image of 'Shantesvara Mahadeva' and 'Manohara Bhagavati'. The custom of pasting the pictures of Nagas and Vasuki on the doors of houses on the day of Nagapanchami was introduced by him. During his rule, the Buddhists wreaked vengeance on the Hindu Brahmins (especially the followers of Shaivism) for the harm they had received earlier from the Shankaracharya.[citation needed] Shankara Deva tried to pacify the Brahmins harassed by the Buddhists.

Bama Deva, a descendant of Amshuvarma, defeated Shankar Deva in 1080 CE. He suppressed the Nuwakot-Thankuris with the help of nobles and restored the old Solar Dynasty rule in Nepal for the second time. Harsha Deva, the successor of Bama Deva was a weak ruler. There was no unity among the nobles and they asserted themselves in their respective spheres of influence. Taking that opportunity Nanya Deva, a Karnat dynasty king, attacked Nuwakot from Simraungarh. The army successfully defended and won the battle. After Harsha Deva, Shivadeva the third ruled from 1099 to 1126 CE. He founded the town of Kirtipur and roofed the temple of Pashupatinath with gold. He introduced twenty-five paisa coins. After Sivadeva III, Mahendra Deva, Mana Deva, Narendra Deva II, Ananda Deva, Rudra Deva, Amrita Deva, Ratna Deva II, Somesvara Deva, Gunakama Deva II, Lakmikama Deva III and Vijayakama Deva II ruled Nepal in quick succession. Historians differ about the rule of several kings and their respective times. After the fall of the Thakuri dynasty, a new dynasty was founded by Arideva or Ari Malla, known as the 'Malla dynasty'.

Malla dynasty

editEarly Malla rule started with Ari Malla in the 12th century. Over the next two centuries, his kingdom expanded widely, into much of the Indian subcontinent and western Tibet, before disintegrating into small principalities, which later came to be known as the Baise Rajya.

Jayasthiti Malla, with whom commences the later Malla dynasty of the Kathmandu valley, began to reign at the end of the 14th century.This era in the valley is eminent for the various social and economic reforms such as the 'Sanskritization' of the valley people, new methods of land measurement and allocation, etc. In this era, new forms of art and architecture was introduced. The monuments in Kathmandu valley which are listed in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites were built during Malla rule. In the 14th century, before Kathmandu was divided into 3 princely states, Araniko was sent to China upon the request of Abhaya Malla for representing the skill of art and architecture, and he introduced the Pagoda style of architecture to China and subsequently, whole of Asia. Yaksha Malla, the grandson of Jayasthiti Malla, ruled the Kathmandu valley until almost the end of the 15th century. After his demise, the valley was divided into four independent kingdoms—Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Patan, and Banepa—in about 1484 CE. Banepa, however, soon came under the control of Bhaktapur. This division led the Malla rulers into internecine clashes and wars for territorial and commercial gains. Mutually debilitating wars gradually weakened them, which facilitated the conquest of the valley by Prithvi Narayan Shah of Gorkha. The last Malla rulers were Jaya Prakash Malla, Teja Narasingha Malla and Ranjit Malla of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur respectively.

Karnats of Mithila

editThe Simroun, Simroon, Karnat or Dev dynasty originated with an establishment of a kingdom in 1097 CE headquartered at the medieval citadel of Simraungadh on the India-Nepal border:[30]

- Nanya Dev, ruled 1097-1147 CE

- Ganga Dev, ruled 1147-1187 CE

- Narsingh Dev, ruled 1187-1227 CE

- Ramsingh Dev, ruled 1227-1285 CE

- Shaktisingh Dev, ruled 1285-1295 CE

- Harisingh Dev, ruled 1295-1324 CE

In 1324 CE, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq attacked Simroungarh and demolished the fort. The remains are still scattered across the Simroungarh region. The king, Harisingh Dev, fled northwards where his son, Jagatsingh Dev, was married to the widowed princess of Bhaktapur, Nayak Devi.[31]

16th-Century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2024) |

Early modern history

editShah dynasty, Unification of Nepal

editPrithvi Narayan Shah (c. 1768–1775) was the ninth generation descendant of Dravya Shah (1559–1570), the founder of the ruling house of Gorkha. Prithvi Narayan Shah succeeded his father Nara Bhupal Shah to the throne of Gorkha in 1743 CE. King Prithvi Narayan Shah was quite aware of the political situation of the valley kingdoms as well as of the Baise and Chaubise principalities. He foresaw the need for unifying the small principalities as an urgent condition for survival in the future and set himself to the task accordingly.

His assessment of the situation among the hill principalities was correct, and the principalities were subjugated fairly easily. King Prithvi Narayan Shah's victory march began with the conquest of Nuwakot, which lies between Kathmandu and Gorkha, in 1744. After Nuwakot, he occupied strategic points in the hills surrounding the Kathmandu valley. The valley's communications with the outside world were thus cut off. The occupation of the Kuti Pass in about 1756 stopped the valley's trade with Tibet. Finally, Prithvi Narayan Shah entered the valley. After the victory in Kirtipur, King Jaya Prakash Malla of Kathmandu sought help from the British and the then East India Company sent a contingent of soldiers under Captain Kinloch in 1767. The British force was defeated in Sindhuli by the Gorkhali army. This defeat of the British completely shattered the hopes of King Jaya Prakash Malla. On 25 September 1768, as the people of Kathmandu were celebrating the festival of Indra Jatra, the Gorkhali army marched into the city. Prithvi Narayan Shah sat on a throne put on the palace courtyard for the king of Kathmandu, proclaiming himself the king. Jaya Prakash Malla somehow managed to escape and took asylum in Patan. When Patan was captured a few weeks later, both Jaya Prakash Malla and Tej Narsingh Malla, the king of Patan took refuge in Bhaktapur, which was captured on the night of 25 November 1769. The Kathmandu valley was thus conquered by King Prithvi Narayan Shah, who proclaimed himself King with Kathmandu as the royal capital of the Kingdom of Nepal.[32]

King Prithvi Narayan Shah was successful in bringing together diverse religious-ethnic groups under one rule. He was a true nationalist in his outlook and was in favour of adopting a closed-door policy against the British. Not only did his social and economic views guide the country's socio-economic course for a long time, but his use of the imagery of "a yam between two boulders" in Nepal's geopolitical context formed the principal guideline of the country's foreign policy for future centuries.

Senas of Makwanpur

editIn the 16th century, a dynasty emerged in the southern parts of Nepal near the border with Bihar which used the Sena surname and claimed descent from the Senas of Bengal. One of their branches formed the Sena dynasty of Makwanpur which ruled from the fort of Makwanpur Gadhi.[33] This branch of the Sena dynasty adopted the local language of the region, Maithili which became their state language.[34]

Modern history

editKingdom of Nepal

editAfter decades of rivalry between the medieval kingdoms, modern Nepal was unified in the latter half of the 18th century, when Prithvi Narayan Shah, the ruler of the small principality of Gorkha, formed a unified country from a number of independent hill high states. After the death of Prithvi Narayan Shah, the Shah dynasty began to expand their kingdom into much of the Indian subcontinent. Between 1788 and 1791, during the Sino-Nepalese War, Nepal invaded Tibet and robbed Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse. Alarmed, the Qianlong Emperor of the Chinese Qing dynasty appointed Fuk'anggan commander-in-chief of the Tibetan campaign; Fuk'anggan signed a treaty to protect his troops thus attaining a draw.[35]

After 1800, the heirs of Prithvi Narayan Shah proved unable to maintain firm political control over Nepal. A period of internal turmoil followed. The rivalry between Nepal and the British East India Company over the princely states bordering Nepal and British-India eventually led to the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–16), in which Nepal suffered substantial losses due to lack of guns and ammunitions against the British-Indian forces with advanced weapons. The Treaty of Sugauli was signed in 1816, ceding large parts of the Nepalese controlled territories to the British. In 1860 some parts of western Terai, known as Naya Muluk (new country) was restored to Nepal. The four noble families involved largely in the active politics of the kingdom were the Shah rulers, the Thapas, the Basnyats, and the Pandes before the rise of the Rana dynasty.[36] From beginning to the mid of 18th century, the Thapas and Pandes had extreme dominance over Nepalese Darbar politics alternatively contesting for central power amongst each other.[37]

Rana rule

editJung Bahadur Rana was the first ruler from this dynasty. Rana rulers were titled "Shree Teen" and "Maharaja", whereas Shah kings were "Shree Panch" and "Maharajadhiraja". Jung Bahadur codified laws and modernized the state's bureaucracy. In the coup d'état of 1846, the nephews of Jung Bahadur and Ranodip Singh murdered Ranodip Singh and the sons of Jung Bahadur, adopted the name of Jung Bahadur and took control of Nepal. Nine Rana rulers took the hereditary office of Prime Minister. All were styled (self proclaimed) Maharaja of Lamjung and Kaski.

The Rana regime, a tightly centralized autocracy, pursued a policy of isolating Nepal from external influences. This policy helped Nepal maintain its independence during the British colonial era, but it also impeded the country's economic development and modernisation. The Ranas were staunchly pro-British and assisted the British during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and later in both World Wars. At the same time, despite Chinese claims, the British supported Nepalese independence at the beginning of the twentieth century.[38] In December 1923, Britain and Nepal formally signed a "treaty of perpetual peace and friendship" superseding the Sugauli Treaty of 1816 and upgrading the British resident in Kathmandu to an envoy.

Slavery was abolished in Nepal in 1924 under premiership of Chandra Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana.[39]

Following the German invasion of Poland, the Kingdom of Nepal declared war on Germany on 4 September 1939. Once Japan entered the conflict, sixteen battalions of the Nepali Army fought on the Burmese front. In addition to military support, Nepal contributed guns, equipment as well as hundreds of thousand of pounds of tea, sugar and raw materials such as timber to the Allied war effort.

Revolution of 1951

editThe revolution of 1951 started when dissatisfaction against the family rule of the Ranas started emerging from among the few educated people, who had studied in various South Asian schools and colleges, and also from within the Ranas, many of whom were marginalized within the ruling Rana hierarchy. Many of these Nepalese in exile had actively taken part in the Indian Independence struggle and wanted to liberate Nepal as well from the autocratic Rana occupation. The political parties such as the Praja Parishad and Nepali Congress were already formed in exile by leaders such as B. P. Koirala, Ganesh Man Singh, Subarna Sumsher Rana, Krishna Prasad Bhattarai, Girija Prasad Koirala, and many other patriotic-minded Nepalis who urged the military and popular political movement in Nepal to overthrow the autocratic Rana regime. The Nepali Congress also formed a military wing Nepali Congress's Liberation Army. Among the prominent martyrs to die for the cause, executed at the hands of the Ranas, were Dharma Bhakta Mathema, Shukraraj Shastri, Gangalal Shrestha, and Dasharath Chand who were the members of the Praja Parisad. This turmoil culminated in King Tribhuvan, a direct descendant of Prithvi Narayan Shah, fleeing from his "palace prison" in 1950, to India, touching off an armed revolt against the Rana administration. This eventually ended in the return of the Shah family to power and the appointment of a non-Rana as prime minister following a tri-partite agreement signed called 'Delhi Compromise'. A period of quasi-constitutional rule followed, during which the monarch, assisted by the leaders of fledgling political parties, governed the country. During the 1950s, efforts were made to frame a constitution for Nepal that would establish a representative form of government, based on a British model. A 10-member cabinet under Prime Minister Mohan Shumsher with 5 members of the Rana family and 5 of the Nepali Congress was formed. This government drafted a constitution called the 'Interim Government Act' which was the first constitution of Nepal. But this government failed to work in consensus as the Ranas and Congressmen were never on good terms. So, on 16 November 1951, the king formed a new government of 14 ministers under Matrika Prasad Koirala, which was later dissolved.

Panchayat system

editThe first democratic elections were held in 1959, and B. P. Koirala was elected prime minister. But declaring parliamentary democracy a failure, King Mahendra carried out a royal coup 18 months later, in 1960. He dismissed the elected Koirala government, declared that a "partyless" system would govern Nepal, and promulgated a new constitution on 16 December 1960. Subsequently, the elected prime minister, members of parliament and hundreds of democratic activists were arrested.

The new constitution established a "partyless" Panchayat system which King Mahendra considered to be a democratic form of government, closer to Nepalese traditions. As a pyramidal structure, progressing from village assemblies to the Rastriya Panchayat, the Panchayat system constitutionalized the absolute power of the monarch and kept the King as head of state with sole authority over all governmental institutions, including the cabinet (council of ministers) and the parliament. One-state-one-language became the national policy in an effort to carry out state unification, uniting various ethnic and regional groups into a singular Nepali nationalist bond. The Back to Village Campaign (Nepali: गाउँ फर्क अभियान) launched in 1967, was one of the main rural development programs of the Panchayat system.

King Mahendra was succeeded by his 27-year-old son, King Birendra, in 1972. Amid student demonstrations and anti-regime activities in 1979, King Birendra called for a national referendum to decide on the nature of Nepal's government; either the continuation of the Panchayat system along with democratic reforms or the establishment of a multiparty system. The referendum was held in May 1980, and the Panchayat system gained a narrow victory. The king carried out the promised reforms, including selection of the prime minister by the Rastriya Panchayat.

Multiparty democracy

editPeople in rural areas had expected that their interests would be better represented after the adoption of parliamentary democracy in 1990. The Nepali Congress with the support of the United Left Front decided to launch a decisive agitational movement, the Jana Andolan, which forced the monarchy to accept constitutional reforms and to establish a multiparty parliament. In May 1991, Nepal held its first parliamentary elections in nearly 50 years. The Nepali Congress won 110 of the 205 seats and formed the first elected government in 32 years.

In 1992, in a situation of economic crisis and chaos, with spiraling prices as a result of the implementation of changes in policy of the new Congress government, the radical left stepped up their political agitation. A Joint People's Agitation Committee was set up by the various groups.[40] A general strike was called for 6 April. Violent incidents began to occur on the eve of the strike. The Joint People's Agitation Committee had called for a 30-minute 'lights out' in the capital, and violence erupted outside Bir Hospital when activists tried to enforce the 'lights out'. At dawn on 6 April, clashes between strike activists and police, outside a police station in Pulchowk, Lalitpur, which left two activists dead. Later in the day, a mass rally of the Agitation Committee at Tundikhel in the capital Kathmandu was attacked by police forces. As a result, riots broke out and the Nepal Telecommunications building was set on fire; police opened fire at the crowd, killing several persons. The Human Rights Organisation of Nepal estimated that 14 persons, including several onlookers, had been killed in police firing.[41]

When promised land reforms failed to appear, people in some districts started to organize to enact their own land reform and to gain some power over their lives in the face of usurious landlords. However, this movement was repressed by the Nepali government, in "Operation Romeo" and "Operation Kilo Sera II", which took the lives of many of the leading activists of the struggle. As a result, many witnesses to this repression became radicalized.

Nepalese Civil War

editIn March 1997, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) started a bid to replace the parliamentary monarchy with a new people's democratic republic, through a Maoist revolutionary strategy known as the people's war, which led to the Nepalese Civil War. Led by Dr. Baburam Bhattarai and Pushpa Kamal Dahal (also known as "Prachanda"), the insurgency began in five districts in Nepal: Rolpa, Rukum, Jajarkot, Gorkha, and Sindhuli. The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) established a provisional "people's government" at the district level in several locations.

On 1 June 2001, Prince Dipendra, went on a shooting-spree, assassinating 9 members of the royal family, including King Birendra and Queen Aishwarya, before shooting himself. Due to his survival, he temporarily became king before dying of his wounds, after which Prince Gyanendra (King Birendra's brother) inherited the throne, as per tradition. Meanwhile, the rebellion escalated, and in October 2002 the king temporarily deposed the government and took complete control of it. A week later he reappointed another government, but the country was still very unstable.

Large parts of Nepal were taken over by the rebellion. The Maoists are driving out representatives of parties close to the government, expropriating local "capitalists" and implementing their own development projects. They also run their own prisons and courts. In addition to coercive measures, the guerrillas are gaining a foothold because of their popularity with large sectors of Nepalese society, particularly women, untouchables and ethnic minorities. Caste discrimination was abolished, women received equal inheritance rights and forced marriages were prohibited. In addition, the Maoists provided free health care and literacy classes.[42]

In the face of unstable governments and a siege on the Kathmandu Valley in August 2004, popular support for the monarchy began to wane. On 1 February 2005, King Gyanendra dismissed the entire government and assumed full executive powers, declaring a state of emergency to quash the revolution. Politicians were placed under house arrest, phone and internet lines were cut, and freedom of the press was severely curtailed.

The king's new regime made little progress in his stated aim to suppress the insurgents. Municipal elections in February 2006 were described by the European Union as "a backward step for democracy", as the major parties boycotted the election and some candidates were forced to run for office by the army.[43] In April 2006 strikes and street protests in Kathmandu forced the king to reinstate the parliament.[44] A seven-party coalition resumed control of the government and stripped the king of most of his powers. On 24 December 2007, seven parties, including the former Maoist rebels and the ruling party, agreed to abolish the monarchy and declare Nepal a federal republic.[45] In the elections held on 10 April 2008, the Maoists secured a simple majority, with the prospect of forming a government to rule the proposed 'Republic of Nepal'.

From 1996 to 2006, the war resulted in approximately 13,000 deaths. According to the NGO Informal Sector Service Centre, 85 per cent of civilian killings are attributable to government actions.[46]

Republic

editOn 28 May 2008, the newly elected Constituent Assembly declared Nepal a Federal Democratic Republic, abolishing the 240-year-old monarchy. The motion for the abolition of the monarchy was carried by a huge majority: out of 564 members present in the assembly, 560 voted for the motion while 4 members voted against it.[47] On 11 June 2008, the deposed King Gyanendra left the palace.[48] Ram Baran Yadav of the Nepali Congress became the first President of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal on July 23, 2008. Similarly, the Constituent Assembly elected Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda) of the Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) as the first Prime Minister of the republic on 15 August 2008, favoring him over Sher Bahadur Deuba of the Nepali Congress.[49]

After failing to draft a constitution before the deadline, the existing Constituent Assembly was dissolved by the government on 28 May 2012 and a new interim government was formed under the premiership of the Chief Justice of Nepal, Khil Raj Regmi. In the Constituent Assembly election of November 2013, the Nepali Congress won the largest share of the votes but failed to get a majority. The CPN (UML) and the Nepali Congress negotiated to form a consensus government, and Sushil Koirala of the Nepali Congress was elected as prime minister.[50] The Constitution of Nepal was finally adopted on 20 September 2015.[51]

On 25 April 2015, a devastating earthquake of moment magnitude of 7.8Mw killed nearly 9,000 people and injured nearly 22,000. It was the worst natural disaster to strike the country since the 1934 Nepal–Bihar earthquake. The earthquake also triggered an avalanche on Mount Everest, killing 21. Centuries-old buildings including the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the Kathmandu valley were destroyed. A major aftershock occurred on 12 May 2015 at 12:50 NST with a moment magnitude (Mw) of 7.3, killing more than 200 people and over 2,500 were injured by this aftershock, and many were left homeless. These events led to a major humanitarian crisis which affected the reconstruction after the earthquake.[52]

Minority ethnic groups like Madhesi and Tharu protested vigorously against the constitution which came into effect on 20 September 2015.[53] They pointed out that their concerns had not been addressed and there were few explicit protections for their ethnic groups in the document. At least 56 civilians and 11 police died in clashes over the constitution.[54] In response to the Madhesi protests, India suspended vital supplies to landlocked Nepal, citing insecurity and violence in border areas.[55] The then prime minister of Nepal, KP Sharma Oli, publicly accused India for the blockade calling the act more inhumane than war.[56] India has denied enacting the blockade.[57] The blockade choked imports of not only petroleum, but also medicines and earthquake relief material.[58] The then United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, alleged that the denial of petroleum and medicine to Nepal constituted a violation of human rights, adding to the humanitarian crisis.[59]

2017 to present

editIn June 2017, Nepali Congress leader Sher Bahadur Deuba was elected the 40th Prime Minister of Nepal, succeeding Prime Minister and Chairman of CPN (Maoist Centre) Pushpa Kamal Dahal. Deuba had been previously Prime Minister from 1995 to 1997, from 2001 to 2002, and from 2004 to 2005.[60] In November 2017, Nepal had its first general election since the civil war ended and the monarchy was abolished. The main alternatives were centrist Nepali Congress Party and the alliance of former Maoist rebels and the Communist UML party.[61] The alliance of communists won the election, and UML leader Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli was sworn in February 2018 as the new Prime Minister. He had previously been Prime Minister since 2015 until 2016.[62]

In March 2018, President Bidya Devi Bhandari, the candidate of the then-ruling Left alliance of the CPN-UML and CPN (Maoist Centre), was re-elected for a second term. The presidential post is mainly ceremonial.[63]

In July 2021, Prime Minister Oli was replaced by Sher Bahadur Deuba after a constitutional crisis.[64]

In December 2022, former Maoist guerilla chief, Pushpa Kamal Dahal aka Prachanda, became Nepal's new prime minister after the general election.[65]

In March 2023, Ram Chandra Paudel of Nepali Congress was elected as Nepal's third president to succeed Bidya Devi Bhandari.[66]

On 15 July 2024, K. P. Sharma Oli was sworn in as Nepali Prime minister for fourth time. New coalition was formed between Nepali Congress, led by Sher Bahadur Deuba, and UML, led by Oli. The party leaders will take turns as prime ministers for 18 months each until the next general elections in 2027.[67]

Literature

edit- Munchi Shew Shunker Singh and Pandit Shri Gunanand. History of Nepal, translated from the Parbatiya. With an introductory sketch of the Country and people of Nepal by the editor, Daniel Wright. Cambridge, at the University Press, 1877. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Nepal," pp. 609-610., p. 609, at Google Books

- ^ Shaha, Rishikesk (1992). Ancient and medieval nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar. p. 2. ISBN 9788185425696.

- ^ a b c d Bhattarai, Krishna P. (2008). Nepal. Internet Archive. New York : Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-7910-9672-7.

- ^ Shaha, Rishikesk (1992). Ancient and medieval nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9788185425696.

- ^ "The Prehistory of Nepal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2022.

- ^ Krishna P. Bhattarai (2009). Nepal. Infobase publishing. ISBN 9781438105239.

- ^ Brega, A; Gardella, R; Semino, O; Morpurgo, G; Astaldi Ricotti, G B; Wallace, D C; Santachiara Benerecetti, A S (October 1986). "Genetic studies on the Tharu population of Nepal: restriction endonuclease polymorphisms of mitochondrial DNA". American Journal of Human Genetics. 39 (4): 502–512. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1683983. PMID 2876631.

- ^ a b Hodgson, B. H. (Brian Houghton) (1880). Miscellaneous essays relating to Indian subjects. Robarts - University of Toronto. London, Trübner.

- ^ Social Inclusion of Ethnic Communities in Contemporary Nepal. KW Publishers Pvt Ltd. 15 August 2013. pp. 199–. ISBN 978-93-85714-70-2.

- ^ Sarkar, Jayanta; Ghosh, G. C. (2003). Populations of the SAARC Countries: Bio-cultural Perspectives. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788120725621.

- ^ Susi Dunsmore British Museum Press, 1993 - Crafts & Hobbies - 204 pages

- ^ Ghosh, A. (1967). "The Pillars of Aśoka - Their Purpose". East and West. 17 (3/4): 273–275. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29755169.

- ^ Vincent A. Smith (1 December 1958). Early History of India. Internet Archive. Oxford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-19-821513-4.

249 BCE, Pilgrimage of Asoka to Buddhist holy places; erection of pillars at Lumbini Garden and near a stupa of Konakamana; his visit to Nepal, and foundation of Lalita Patan his daughter Charumati becomes a nun.

- ^ Sen, Gercrude Emerson (1948). Pageant Of India's History Vol.1. Longmans, Green And Co. New York. p. 131.

Asoka is also credited with having founded two important cities, Srinagar in Kashmir and Lalita Patan in Nepal.

- ^ "Kirates in Ancient India by G.P. Singh/ G.P. Singh: South Asia Books 9788121202817 Hardcover - Revaluation Books". abebooks.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ Shaha, Rishikesh. Ancient and Medieval Nepal (1992), p. 7. Manohar Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85425-69-8.

- ^ Groeger, Herbert; Trenkler, Luigi (2005). "Zen and systemic therapy: Similarities, distinctions, possible contributions of Zen theory and Zen practice to systemic therapy" (PDF). Brief Strategic and Systematic Therapy European Review. 2: 2.

- ^ Srivastava, K.M. (1980), "Archaeological Excavations at Priprahwa and Ganwaria and the Identification of Kapilavastu", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 3 (1): 108

- ^ Tuladhar, Swoyambhu D. (November 2002), "The Ancient City of Kapilvastu - Revisited" (PDF), Ancient Nepal (151): 1–7

- ^ Huntington, John C (1986), "Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus" (PDF), Orientations, September 1986: 54–56, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2014

- ^ Vaidya, Tulasī Rāma (1985). Crime and Punishment in Nepal: A Historical Perspective. Bini Vaidya and Purna Devi Manandhar.

- ^ Regmi, D. R.; Studies, Nepal Institute of Asian (1969). Ancient Nepal. Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

- ^ Shaha, Rishikesh (2001). An Introduction to Nepal. Ratna Pustak Bhandar. p. 39.

- ^ Singh, G. P. (2008). Researches Into the History and Civilization of the Kirātas. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-212-0281-7.

- ^ Khatri, Tek Bahadur (1973). The Postage Stamps of Nepal. Sharada Kumari K.C.

- ^ Khatri, Shiva Ram (1999). Nepal Army Chiefs: Short Biographical Sketches. Sira Khatri.

- ^ Ḍhakāla, Bāburāma (2005). Empire of Corruption. Babu Ram Dhakal. ISBN 978-99946-33-91-3.

- ^ a b "The Lichhavi and Kirat kings of Nepal". telegraphnepal.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ a b Fleet, John Faithfull (1888). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol. 3. pp. 6–10.

- ^ Chaudhary, Radhakrishna. Mithilak Itihas. Ram Vilas Sahu. ISBN 9789380538280.

- ^ Prinsep, James (March 1835). Prinsep, James (ed.). "The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Ed. By James Prinsep". The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 4 (39).

- ^ "Nepal - History".

- ^ Basudevlal Dad (2014). "The Sena Dynasty: From Bengal to Nepal". Academic Voices. 4.

- ^ Das, Basudevlal (2013). "Maithili in Medieval Nepal: A Historical Apprisal". Academic Voices. 3: 1–3. doi:10.3126/av.v3i1.9704.

- ^ "Nepalese Army | नेपाली सेना". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ Joshi & Rose 1966, p. 23.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Matteo Miele (2017). "British Diplomatic Views on Nepal and the Final Stage of the Ch'ing Empire (1910–1911)" (PDF). Prague Papers on the History of International Relations. pp. 90–101. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ Tucci, Giuseppe. (1952). Journey to Mustang, 1952. Trans. by Diana Fussell. 1st Italian edition, 1953; 1st English edition, 1977. 2nd edition revised, 2003, p. 22. Bibliotheca Himalayica. ISBN 99933-0-378-X (South Asia); 974-524-024-9 (Outside of South Asia).

- ^ The organisers of the Committee were the Samyukta Janamorcha Nepal, the Communist Party of Nepal (Unity Centre), Communist Party of Nepal (Masal), the Nepal Communist League and the Communist Party of Nepal (Marxist-Leninist-Maoist).

- ^ Hoftun, Martin, William Raeper and John Whelpton. People, politics and ideology: Democracy and Social Change in Nepal. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point, 1999. p. 189

- ^ Cédric Gouverneur (21 March 2004). "Social Inequality, Grinding Poverty, State Negligence". The Blanket.

- ^ When a king's looking-glass world is paid for in blood. Guardian. 2 February 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ "Nepal travel". Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Nepal votes to abolish monarchy. CNN. 28 December 2007

- ^ "Conflict Victim's Profile".

- ^ Nepalnews.com, news from Nepal as it happens Archived 2016-01-17 at the Wayback Machine. Nepalnews.com. 28 May 2008. Retrieved on 2012-04-08.

- ^ Ex-King Gyanendra leaves Narayanhiti. nepalnews.com. 11 June 2008

- ^ "Nepal's former guerrilla chief Prachanda sworn in as PM". Reuters. 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Sushil Koirala wins vote to be Nepal's prime minister". BBC News. 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Why is Nepal's new constitution controversial?". BBC News. 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Asian Disaster Reduction Center(ADRC)" (PDF). www.adrc.asia.

- ^ Pokharel, Krishna (23 September 2015). "Nepal's New Constitution – at a Glance". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Why is Nepal's new constitution controversial?". BBC News. 19 September 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Nepal Will Amend Constitution to End Border Blockade". Time. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Indian blockade more inhuman than war, says Nepal PM KP Sharma Oli | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 6 November 2015.

- ^ "India denies imposing economic blockade on Nepal". 9 October 2015.

- ^ Arora, Vishal. "R.I.P., India's Influence in Nepal". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Right to Nepal's Right Path". BBC News (in Nepali). 11 November 2015.Google Translation

- ^ "Sher Bahadur Deuba elected 40th PM of Nepal".

- ^ "Nepal election: First poll since civil war ended". BBC News. 26 November 2017.

- ^ "Nepal country profile". BBC News. 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Bidya Devi Bhandari re-elected as Nepal President". The Hindu. 13 March 2018.

- ^ Sharma, Gopal (18 July 2021). "Nepal's new PM wins confidence vote amid coronavirus crisis". Reuters.

- ^ "Former Rebel Leader Becomes Nepal's New PM". VOA.

- ^ "Nepal elects new president amid split in the governing coalition". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Oli becomes prime minister for fourth time, swearing-in today". kathmandupost.com.

Sources

edit- Michaels, Axel, et al. "Nepalese History in a European Experience: A Case Study in Transcultural Historiography." History and Theory 55.2 (2016): 210–232.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "A Sanskrit Letter Written by Sylvain Lévi in 1923 to Hemarāja Śarmā Along With Some Hitherto Unknown Biographical Notes (Cultural Nationalism and Internationalism in the First Half of the 21st Cent.: Famous Indologists Write to the Raj Guru of Nepal – no. 1), in Commemorative Volume for about 30 Years of the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project. Journal of the Nepal Research Centre, XII (2001), Kathmandu, ed. by A. Wezler in collaboration with H. Haffner, A. Michaels, B. Kölver, M. R. Pant and D. Jackson, pp. 115–149.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Strage a palazzo, movimento dei Maoisti e crisi di governabilità in Nepal", in Asia Major 2002, pp. 143–160.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Il nuovo Stato del Nepal: il difficile cammino dalla monarchia assoluta alla democrazia", in Asia Major 2005-2006, pp. 229–251.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Il Nepal da monarchia a stato federale", in Asia Major 2008, pp. 163–181.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "La fine dell'isolamento del Nepal, la costruzione della sua identità politica e delle sue alleanze regionali" in ISPI: Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionali, CVII (Nov. 2008), pp. 1–7;

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Le elezioni dell'Assemblea Costituente e i primi mesi di governo della Repubblica Democratica Federale del Nepal", in Asia Maior 2010, pp. 115–126.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Nepal, la difficile costruzione della nazione: un paese senza Costituzione e un parlamento senza primo ministro", in Asia Maior 2011, pp. 161–171.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "The Interplay between Gender, Religion and Politics, and the New Violence against Women in Nepal", in J. Dragsbæk Schmidt and T. Roedel Berg (eds.), Gender, Social Change and the Media: Perspective from Nepal, University of Aalborg and Rawat Publications, Aalborg-Jaipur: 2012, pp. 27–91.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Nepal, stallo politico e lentezze nella realizzazione del processo di pace e di riconciliazione", in Asia Maior 2012, pp. 213–222.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "A Sanskrit Letter Written by Sylvain Lévy in 1925 to Hemarāja Śarmā along with Some Hitherto Unknown Biographical Notes (Cultural Nationalism and Internationalism in the First Half of the 20th Century – Famous Indologists write to the Raj Guru of Nepal – No. 2)", in History of Indological Studies. Papers of the 12th World Sanskrit Conference Vol. 11.2, ed. by K. Karttunen, P. Koskikallio and A. Parpola, Motilal Banarsidass and University of Helsinki, Delhi 2015, pp. 17–53.

- Garzilli, Enrica, "Nepal 2013-2014: Breaking the Political Impasse", in Asia Maior 2014, pp. 87–98.

- Joshi, Bhuwan Lal; Rose, Leo E. (1966), Democratic Innovations in Nepal: A Case Study of Political Acculturation, University of California Press, p. 551

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132

- Tiwari, Sudarshan Raj (2002). The Brick and the Bull: An account of Handigaun, the Ancient Capital of Nepal. Himal Books. ISBN 99933-43-52-8.

- Kayastha, Chhatra Bahadur (2003).Nepal Sanskriti: Samanyajnan. Nepal Sanskriti. ISBN 99933-34-84-7.

- Stiller, Ludwig (1993): Nepal: growth of a nation, HRDRC, Kathmandu, 1993, 215pp.

External links

edit- Nepal: An Historical Study of a Hindu Kingdom (in English and French)

- History of Nepal