This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

Palestrina (ancient Praeneste; Ancient Greek: Πραίνεστος, Prainestos) is a modern Italian city and comune (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about 35 kilometres (22 miles) east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon the ruins of the ancient city of Praeneste.

Palestrina | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Palestrina | |

| |

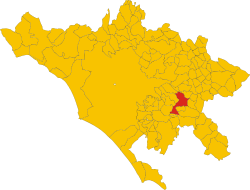

Location of Palestrina in the Metropolitan City of Rome Capital | |

| Coordinates: 41°50′N 12°54′E / 41.833°N 12.900°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Lazio |

| Metropolitan city | Rome (RM) |

| Area | |

• Total | 47.02 km2 (18.15 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 450 m (1,480 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2017)[2] | |

• Total | 21,872 |

| • Density | 470/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Palestrinesi o Prenestini |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 00036 (capital, Valvarino), 00030 (Carchitti) |

| Dialing code | 06 |

| Patron saint | St. Agapitus martyr |

| Saint day | August 18 |

| Website | Official website |

Palestrina is the birthplace of composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.

Geography

editPalestrina is sited on a spur of the Monti Prenestini, a mountain range in the central Apennines.

Modern Palestrina borders the following municipalities: Artena, Castel San Pietro Romano, Cave, Gallicano nel Lazio, Labico, Rocca di Cave, Rocca Priora, Rome, San Cesareo, Valmontone, Zagarolo.

History

editAncient Praeneste

editAncient mythology connected the origin of Praeneste to Ulysses, or to other fabled characters such as Caeculus, Telegonus, Erulus or Praenestus. The name probably derives from the word Praenesteus, referring to its overlooking location.

Early burials show that the site was already occupied in the 8th or 7th century BC. The ancient necropolis lies on a plateau at the foot of the hill below the ancient town. Of the objects found in the oldest graves, and supposed to date from about the 7th century BC, the cups of silver and silver-gilt and most of the gold and amber jewelry are Phoenician (possibly Carthaginian), but the bronzes and some of the ivory articles seem to be of the Etruscan civilization.[3]

Praeneste was probably under the hegemony of Alba Longa while that city was the head of the Latin League. It withdrew from the league in 499 BC, according to Livy (its earliest historical mention), and formed an alliance with Rome, the action which led to a battle between the latter and thirty Latin states.[4] After Rome was weakened by the Gauls of Brennus (390 BC), Praeneste switched allegiances and fought against Rome in the long struggles that culminated in the Latin War. From 373 to 370, it was in continual war against Rome or her allies, and was defeated by Cincinnatus.

Republican Rome

editEventually in 354 and in 338 the Romans were victorious and Praeneste was punished by the loss of portions of its territory, becoming a city allied to Rome. As such, it furnished contingents to the Roman army, and Roman exiles were permitted to live at Praeneste, which grew prosperous. The roses of Praeneste were a byword for profusion and beauty. Præneste was situated on the Via Praenestina.

Praenestine graves from about 240 BC onwards have been found: they are surmounted by the characteristic cippus made of local stone, containing stone coffins with rich bronze, ivory and gold ornaments beside the skeleton. From these come the famous bronze boxes (cistae) and hand mirrors with inscriptions partly in Etruscan. Also famous is the bronze Ficoroni Cista[7] (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome), engraved with pictures of the arrival of the Argonauts in Bithynia and the victory of Pollux over Amycus, found in 1738. An example of archaic Latin is the inscription on the Ficoroni Cista: "Novios Plautios Romai med fecid / Dindia Macolnia fileai dedit" ("Novios Plautios made me in Rome, Dindia Macolnia gave me to her daughter"). The caskets are unique in Italy, but a large number of mirrors of precisely similar style have been discovered in Etruria. Hence, although it would be reasonable to conjecture that objects with Etruscan characteristics came from Etruria, the evidence points decisively to an Etruscan factory in or near Praeneste itself. Other imported objects in the burials show that Praeneste traded not only with Etruria but also with the Greek east.

Its citizens were offered Roman citizenship in 90 BC in the Social War, when concessions had to be made by Rome to cement necessary alliances. In Sulla's civil war, Gaius Marius was blockaded in the town by the forces of Sulla (82 BC). When the city was captured, Marius slew himself, the male inhabitants were massacred in cold blood, and a military colony was settled on part of its territory. From an inscription it appears that Sulla delegated the foundation of the new colony to Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus, who was consul in 73 BC. Within a decade the lands of the colonia had been assembled by a few large landowners.

From the late Republic to the late Empire, markets, baths, shrines and even a second forum were built in the lower city, near today's Madonna dell'Aquila.[8]

The Empire

editUnder the Empire the cool breezes of Praeneste made it a favourite summer resort of wealthy Romans, whose villas studded the neighbourhood, though they ridiculed the language and the rough manners of the native inhabitants. The poet Horace ranked "cool Praeneste" with Tibur and Baiae as favoured resorts. The emperor Augustus stayed in Praeneste, and Tiberius recovered there from a dangerous illness and made it a municipium. The emperor Marcus Aurelius was at Praeneste with his family when his 7-year-old son Verus died.[9] The ruins of the imperial villa associated with Hadrian stand in the plain near the church of S. Maria della Villa, about three-quarters of a mile from the town. At the site was discovered the statue of the Braschi Antinous, now in the Vatican Museums. Gaius Appuleius Diocles (104 – after 146 AD), a Roman charioteer from Lamego in Lusitania (modern-day Portugal) who became one of the most celebrated athletes in ancient history and is often cited as the highest-paid athlete of all time,[10][11] was living in Praeneste after his retirement and died there. Pliny the Younger also had a villa at Praeneste, and L. Aurelius Avianius Symmachus retired there.[12]

Inscriptions show that the inhabitants of Praeneste were fond of gladiatorial shows.

Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia

editPraeneste was chiefly famed for its great Temple of Fortuna Primigenia connected with the oracle known as the Praenestine lots (sortes praenestinae).

The Forum of Praeneste

editArchaeologists working in the 1950s were able to identify the area around the Cathedral and the Piazza Regina Margherita as the Forum of Ancient Praeneste.[13] The buildings of the forum comprised a central temple, whose walls were re-used for the cathedral, and a two-storey civil basilica consisting of four naves separated by columns, once roofed but today an open space. The basilica was flanked by two buildings, the easternmost containing a raised podium (suggestus)[14] and the public treasury, the aerarium, identified by an inscription dating it to ~150 BC. At some later date (perhaps around 110-100 BC[15]), the buildings flanking the basilica were each embellished with a nymphaeum with a mosaic floor. The western mosaic represents a seascape: a temple of Poseidon on the shore, with fish of all kinds swimming in the sea. The eastern building was decorated with the famous mosaic with scenes from the Nile, relaid in the Palazzo Colonna Barberini [16] in Palestrina on the uppermost terrace (now the National Archaeological Museum of Palestrina).

In the forum area an obelisk was erected in the reign of Claudius, fragments of which can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum of Palestrina.

Roman gentes with origins in Praeneste

editMedieval history

editThe modern town is built on the ruins of the temple of Fortuna Primigenia. A bishop of Praeneste is first mentioned in 313.

In 1297 the Colonna family, which had owned Praeneste (then known as Palestrina) from the eleventh century as a fief, revolted against Pope Boniface VIII. In the following year the town was taken by Boniface's Papal forces, razed to the ground and salted by order of the pontiff.[17]

In 1437 the rebuilt city was captured by Giovanni Vitelleschi, a condottiero in the service of the papacy, and once more utterly destroyed at the command of Pope Eugenius IV.[citation needed] It was rebuilt once more and fortified by Stefano Colonna in 1448. It was sacked in 1527 and occupied by the Duke of Alba in 1556.[citation needed]

Barberini Family

editIn 1630, the comune passed by purchase into the Barberini family.[18] It is likely the transfer was included as one of the conditions of the marriage of Taddeo Barberini and Anna Colonna. Thereafter, the famously nepotistic family, headed by Maffeo Barberini (later Pope Urban VIII), treated the comune as a principality in its own right.

Patriarchs of the Barberini family conferred, on various family members, the title of Prince of Palestrina. During the reign of Urban VIII, the title became interchangeable with that of Commander of the Papal Army (Gonfalonier of the Church) as the Barberini family controlled the papacy and the Palestrina principality.

The Wars of Castro ended (while Taddeo Barberini held both titles) and members of the Barberini family (including Taddeo) fled into exile after the newly elected Pope Innocent X launched an investigation into members of the Barberini family. Later the Barberini reconciled with the papacy when Pope Innocent X elevated Taddeo's son, Carlo Barberini to the cardinalate and his brother Maffeo Barberini married a niece of the Pope and reclaimed the title, Prince of Palestrina.

Two members of the Barberini family were named Cardinal-Bishop of the Diocese of Palestrina: Antonio Barberini and Francesco Barberini (Junior), the son of Maffeo Barberini.

The Barberini Palace originally included the Nile mosaic of Palestrina.

Modern history

editPalestrina was the scene of an 1849 action between Garibaldi and the Neapolitan army during his defence of the Roman Republic.

The centre of the city was destroyed by Allied bombings during World War II; but that brought the ancient remains of the sanctuary to light.

Main sights

editThe modern town of Palestrina is centered on the terraces once occupied by the massive temple of Fortuna. The town came to largely obscure the temple, the monumental remains of which were revealed as a result of American bombing of German positions in World War II. The town also contains remnants of ancient cyclopean walls.

On the summit of the hill at 753 metres (2,470 ft), nearly 1.6 kilometres (1 mi) from the town, stood the ancient citadel, the site of which is now occupied by a few poor houses (Castel San Pietro) and a ruined medieval castle of the Colonna family. The view embraces the Monte Soratte, Rome, the Alban Hills, and the Pontinian Plain as far as the sea. Considerable portions of the southern wall of the ancient citadel, built in massive cyclopean masonry consisting of limestone blocks, are still visible; and the two walls, also polygonal, which formerly united the citadel with the town, can still be traced.

A calendar, which according to Suetonius was set up by the grammarian Marcus Verrius Flaccus in the imperial forum of Praeneste (at the Madonna dell'Aquila), was discovered in 1771 in the ruins of the church of Saint Agapitus, where it had been used as building material.

The cathedral, just below the level of the temple, occupies the former civil basilica of the town, whose façade includes a sundial described by Varro, traces of which may still be seen. In the modern piazza the steps leading up to this basilica and the base of a large monument were found in 1907; evidently only part of the piazza represents the ancient forum. The cathedral has fine paintings and frescoes. In the Church of Santa Rosalia (1677) there is a noteworthy Pietà, carved in the solid rock.

The National Archeological Museum of Palestrina is housed inside the Renaissance Barberini Palace, the former baronial palace, built above the ancient temple of Fortuna. It exhibits the most important works from the ancient town of Praeneste. The famous sculpture of the Capitoline Triad is exhibited on the first floor. The second floor is dedicated to the necropoli and sanctuaries, while the third floor contains a large polychrome mosaic depicting the flooding of the Nile (Nile mosaic of Palestrina).

Famous residents

editPalestrina was the home town of the 3rd-century Roman writer Aelian, and of the great 16th-century composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.

Thomas Mann spent some time there in 1895 and, two years later, during the long harsh summer of 1897, he stayed over again, with his brother Heinrich Mann, in a sojourn that provided the backdrop, nearly half a century later, for Adrian Leverkühn's pact with the Devil in Mann's novel Doktor Faustus.[19]

In popular culture

editIn Inferno, Dante makes reference to advice given by Guido da Montefeltro to Pope Boniface VIII to entice the surrender of Palestrina in 1298 by offering the Colonna family an amnesty. The amnesty was never intended be honored, and instead Palestrina was razed to the ground.[20]

In Voltaire's novel Candide a woman claims to be the daughter of Pope Urban X and the Princess of Palestrina.

A fictional account of Garibaldi's 1849 action at Palestrina appears in Geoffrey Trease's novel Follow My Black Plume.

Twin towns

editSee also

editReferences and sources

edit- References

- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Ralph Van Deman Magoffin (March 2010). A Study of the Topography and Municipal History of Praeneste. General Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-4432-0054-7.

- ^ Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri. pp. II, 19.

- ^ D.B. Saddington (2011) [2007]. "the Evolution of the Roman Imperial Fleets," in Paul Erdkamp (ed), A Companion to the Roman Army, 201-217. Malden, Oxford, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8. Plate 12.2 on p. 204.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (1987), I Santuari del Lazio in età repubblicana. NIS, Rome, pp 35-84.

- ^ it:Cista Ficoroni

- ^ Romanelli, Pietro, Palestrina, Di Mauro Editore, Naples, 1967

- ^ Scriptores Historiae Augustae, "Marcus Aurelius", 21.1

- ^ Struck, Peter T. (2 August 2010). "Greatest of All Time |". Lapham's Quarterly. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Wardrop, Murray (13 August 2010). "Wealth of today's sports stars is 'no match for the fortunes of Rome's chariot racers'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Q. Aurelius Symmachus, Epistulae, Liber I, V

- ^ Mingazzini, Paolino. "Note di topografia prenestina: l’ubicazione dell’Antro delle Sorti", 1954, reproduced in Mingazzini, Paolino, Scritti vari, Giorgio Bretschnider Editore, Rome, 1986.

- ^ Mingazzini, Paolino, op. cit, pages 179-180.

- ^ Tammisto, Antero. "The Nile Mosaic of Palestrina Reconsidered: the Problematic Reconstruction, Identification and Dating of the So-called Lower Complex with the Nile Mosaic and Fish Mosaic of Ancient Praeneste", in: La Mosaïque greco-romaine, IX, Volume I. École française de Rome, 2005. Morlier, Hélène et al, editors. Pages 3-24.

- ^ The Nile Mosaic of Palestrina

- ^ "The Bad Popes" by ER Chamberlin 1969, 1986 ISBN 0-88029-116-8 Chapter III "The Lord of Europe" page 102-104.

- ^ Pietro da Cortona and Roman Baroque architecture, Jörg Martin Merz, Pietro (da Cortona) (p. 31)

- ^ Nigel Hamilton, The Brothers Mann, 1978 p.49

- ^ Sayer, Dorothy L. (1977). Divine Comedy 1 - Hell. Penguine Classics. pp. notes on Canto XXXI. ISBN 978-0140440065.

- Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Frazer, James George; Conway, Robert Seymour; Ashby, Thomas (1911). "Praeneste". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 243–244.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Palestrina". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.