Parts of this article (those related to Parts dependent on older Swedish Crime Surveys (the newest SCS is from 2019)) need to be updated. (January 2020) |

Crime in Sweden is defined by the Swedish Penal Code (Swedish: brottsbalken) and in other Swedish laws and statutory instruments.[2][3]

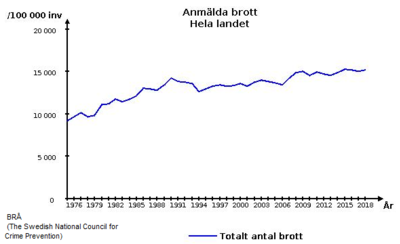

According to the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, the number of reported crimes in Sweden has increased when measured from the 1950s, consistent with other Western countries in the postwar era, which they say can be explained by a number of factors, such as statistical and legislative changes and increased public willingness to report crime.[4]

Legal proceedings

editWhen a crime has been committed the authorities will investigate what has happened, this is known as the preliminary investigation and it will be led by a police officer or prosecutor.[5] The Swedish police and the prosecution service are required to register and prosecute all offences of which they become aware.[6][7][8] The prosecutors are lawyers employed by the Swedish Prosecution Authority, a wholly independent organization not dependent on courts or the police, and not directed by the Ministry of Justice (any ministerial interference is in fact unconstitutional).[9]

The prosecutor are obliged to lead and direct the preliminary investigations of a crime impartially and objective, make decisions on prosecution issues, and appear in court to process actions in criminal cases. Suspects are entitled to a public defense counsel, either during the preliminary investigation stage or during the trial. The suspect is entitled to examine the material gathered by the prosecutor, and is allowed to request the police to conduct further investigation, if he or she considers this to be necessary. A preliminary investigation supervisor decides whether or not these measures can be carried out.[10]

In the case of less serious crimes, if the suspect admits that he/she has committed the offence and it is clear what the punishment should be, the prosecutor can pronounce a so-called order of summary punishment.[5][11] A preliminary investigation not discontinued may result in the prosecutor deciding to prosecute a person for the crime. This means that there will be a trial at the District Court.[5] The person who has been convicted, the prosecutor and the victim of the crime can appeal against the District Court judgement in the Court of Appeal.[12]

Confidence in the criminal justice system

editSix out of ten respondents surveyed in the SCS 2013 said they had a high level of confidence in the criminal justice system as a whole, and the police enjoyed similarly high confidence levels. Of the crime victims, a little over half of all surveyed (57%) stated that their experience of the police was generally positive, and nearly one in seven stated that the experience was negative.[13][non-primary source needed]

Corruption

editIn general, the level of corruption in Sweden is very low.[14] The legal and institutional framework in Sweden are considered effective in fighting against corruption, and the government agencies are characterized by a high degree of transparency, integrity and accountability.[15]

Since 2015, corruption levels have been rising[16][17] and the country has steadily fallen in international anti-corruption rankings.[18][19] Research conducted by Linköping University hinted at a risk of underestimated corruption levels in the country.[20]

Crime statistics

editSweden began recording national crime statistics in 1950, and the method for recording crime has basically remained unchanged until the mid-1960s, when the Swedish police introduced new procedures for crime statistics, which have been presented as a partial explanation for the historical increase in crime reports.[4] In 1974, the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Swedish: Brottsförebyggande rådet, abbreviated Brå) became the government agency tasked with producing official statistics and disseminating knowledge on crime.[22][non-primary source needed] In the early 1990s a new crime reporting system was implemented, which meant that the manual controls became less frequent, resulting in an additional increase in the number of reported crimes.[23][non-primary source needed]

In January 2017, the Löfven cabinet denied the request from member parliament Staffan Danielsson to update the BRÅ statistics on crime with respect to national or immigration background of the perpetrator, as had previously been done in 1995, 2005 but the 2015 was overdue.[24]

According to a 2013 Swedish Crime Survey (SCS) by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, exposure to crime decreased from 2005 to 2013.[25][non-primary source needed] Since 2014, reports from the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention say that there has been an increase in exposure to some categories of crimes, including fraud, some property crime and sexual offences according to the 2016 SCS.[26]: 5–7 [non-primary source needed] Crimes falling under threats, harassment, assault and robbery continued to climb through 2018.[27][non-primary source needed] The increase in reports of sexual offenses is, in part, due to campaigns to encourage reporting, combined with changes to the laws that broadened the legal definition of rape.[28]

The figures for fraud and property damage (excluding car theft) are in contrast with the numbers of reported crimes under such categories which have remained roughly constant over the period 2014–16.[29] The number of reported sexual offences clearly reflect the figures in the 2016 SCS, and car related damages/theft are also somewhat reflected.[30][31] The number of convictions up to 2013 has remained between 110,000 and 130,000 in the 2000s — a decrease since the 1970s, when they numbered around 300,000 — despite the population growth.[32][non-primary source needed]

In November 2023, The Guardian published five charts suggesting that violence is linked with poverty, inequality, and narcotics.[33]

International comparison

editComparisons between countries based on official crime statistics (i.e. "crime reports") require caution, since such statistics are produced differently in different countries. Legal and substantive factors also influence the number of reported crimes.[6][7][34][35] For example:

- Sweden applies a system of expansive offence counts for violent crimes, meaning the same crime may be recorded several times, such as in the case of a spousal rape[36] or gang rape. Many other countries employ more restrictive methods of counting.[6][7]

- In Sweden, crime data is collected when the offence in question is first reported, at which point the classification of the offence may be unclear.[6][7] It retains this classification in the published crime statistics, even if later investigations indicate that no crime has been committed.[6]

- The Swedish police and the prosecution service are required to register and prosecute all offences of which they become aware. This can be assumed to lead to a more frequent registration of offences than in systems where the classification of offences is negotiable on the basis of plea bargaining.[6][7]

- Willingness to report crime also affects the statistics.[34] A police force and judicial system enjoining a high level of confidence and a good reputation with the public will produce a higher propensity to report crime than a police force which is discredited, inspires fear or distrust.[6]

Large-scale victimisation surveys have been presented as a more reliable indicator on the level of crime in a given country.[6]

Crime trends

editOffences against the person

editThe level of exposure to offences against the person has decreased somewhat since 2005 (down from 13.1% to 11.4%), according to SCS 2013. Crimes in this group includes assault, threat, sexual offences, mugging, fraud or harassment. In the recently published SCS 2016, exposure to offences has increased to levels as seen prior to 2005, with 13.3% of the people surveyed reporting that they had been victim to one or more of the aforementioned crimes.[26]: 6

Around one in four (26%) surveyed report having experienced these crimes in 2015.[26]

Assault

editWhile the number of reported assaults has been on the increase, crime victim surveys show that a large part of the increase may be due to the fact that more crimes are actually reported.[37] According to the 2013 SCS, the proportion who stated that they have been the victims of assault has declined gradually, from 2.7 per cent in 2005 to 1.9 per cent in 2012. The proportion who are anxious about falling victim to assault has also decreased, from 15 per cent in 2006 to 10 per cent in 2013.[13] This is supported by medical services reporting unchanged levels of incoming patients with wounds derived from assault or serious violent crime.[37][38][39] Studies have also shown that police are increasingly likely to personally initiate reports of assault between strangers, which contributes to more cases involving assault being reported.[40]

In the recently published 2016 SCS 2.0 per cent of the population (ages 16–79) were exposed to assault. Over time, exposure to assault has decreased somewhat, and the percentage of victims has declined by 0.7 percentage points since the survey was first conducted in 2005, reaching its lowest point in 2012 and rising slightly since then. The primary reduction has been among young men.[41]

Exposure to assault is more common for men than women, and most common in the 20–24 age bracket. Assault is most common in a public place and in most cases the perpetrator is unknown to the victim.[26]: 5–7

Sweden has a high rate of reported assault crime when compared internationally,[42] but this can be explained by legal, procedural and statistical differences.[Note 1] For example, the Swedish police applies a system of expansive offence counts for violent crimes, meaning the same crime may be recorded several times.[7] The 2005 European Crime and Safety Survey (2005 EU ICS) found that prevalence victimisation rates for assaults with force was below average in Sweden.[43]

Threats

editIn 2015, 5.0 per cent were exposed to threats. The percentage of persons exposed to threats remained at a relatively stable level between 2005 and 2014.[26]: 5–7

Exposure to threats is more common among women than men, and most common in the 20–24 and 25–34 age brackets.[41]

Murder and homicide

editThe number of cases of lethal violence (Murder, manslaughter, and assault with a lethal outcome) in Sweden remained at a relatively constant level over the period of 2002 to 2016 — on average 92 cases per year.[44]

Since 2015 there has been an increase in the number of cases of lethal violence and the figure in 2017 was the highest in Sweden since 2002.[45][46]

Studies of lethal violence in Sweden have shown that more than half the reported cases were not actually cases of murder or manslaughter. This is because the Swedish crime statistics show all events with a lethal outcome that the police investigate. Many of these reported crimes turn out to be, in reality, suicides, accidents or natural deaths.[38][44] Despite this statistical anomaly, Sweden has an internationally low murder and homicide rate,[Note 2] with approximately 1.14 reported incidents of murder or manslaughter per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2015. The number of "confirmed cases of lethal violence" has fluctuated between 68 and 112 in the period of 2006–2015, with a decrease from 111 in 2007 to 68 in 2012, followed by an increase to 112 in 2015 and a decrease to 106 in 2016.[44] [47][48] Around 75% of those murdered are men.[49] Most cases (71% in 2015) were reported in one of the major metropolitan regions of Stockholm, Väst and Skåne. The largest increase in 2015 was seen in the Väst region, where the number of cases has increased from 14 cases in 2014 to 34 cases in 2015.[44]

In 2016 ten out of the 105 murder cases were honor killings, representing roughly 10% of all murder cases and a third of all murders of women in Sweden.[50]

In May 2017 a survey by Dagens Nyheter showed that of 100 suspects of murder and attempted murder using firearms, 90 had one parent born abroad and 75% were born in the 90s.[51]

According to a comparison of crime statistics from the Norwegian National Criminal Investigation Service (Kripos) and the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brå) done by Norwegian daily newspaper Aftenposten, the murder rate of Sweden has since 2002 been roughly twice that of neighbour country Norway.[52]

Stabbings

editGraphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Knife violence is more common in close relationships, in homes and among socially vulnerable.[54] The number of people treated for knife violence increased by 25% between 2015–2019.[55] Among young people, knife violence has decreased successively since the beginning of the 90s, and remained at the same level between 2015–2020.[56]

Gun violence

editGun violence in Sweden (Swedish: skjutningar or gängskjutningar, "gang shootings") increased steeply among males aged 15 to 29 in the two decades prior to 2015, in addition to a rising trend in gun violence there was also a high rate of gun violence in Sweden compared to other countries in Western Europe.[57]

Gun violence started increasing in the mid 2000s and increased more rapidly from 2013 onwards. This sets Sweden apart from most other countries in Europe where there instead has been a decline in gun homicides. In its 2021 report on the phenomenon, the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention did not analyse the reasons for the trend that occurred in Sweden. Most of the increase is related to gang violence in vulnerable areas in Sweden which are areas with higher crime rates, low income and education, and a large immigrant population.[58]Innocent bystanders

editAccording to police in 2018, at least nine people who were innocent bystanders had been killed in cross-fire incidents in the last few years and the risk to the public was therefore rising.[59]

In 2017, Minister for Justice Morgan Johansson stated in an interview that the risk to "innocent people" was small.[60]

In the 2011–2020 period 46 bystanders had been killed or wounded in 36 shooting incidents. Of these, 8 were under the age of 15. According to researcher Joakim Sturup, a contributing factor could be the increased use of automatic firearms.[61]

Hand grenade attacks and bombings

editGraphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

As of 2019, Sweden is experiencing an unprecedented number of bombings and explosions, though comparisons with previous years are difficult since the criminal use of explosives was not a separate crime category until 2017.[63] In 2018 there were 162 explosions, and in the first nine months of 2019 97 explosions were registered, usually carried out by criminal gangs.

The number of hand grenade detonations in particular has been unusually high, especially in 2016. According to criminologists Manne Gerell and Amir Rostami, the only other country that keeps track of hand grenade explosions is Mexico. While Mexico has a murder rate 20 times that of Sweden, on the specific category of grenade explosions per capita the two countries may be comparable.[63][64] According to Swedish police commissioner Anders Thornberg "No international equivalent to Sweden's wave of bombings".[65] These attacks occurs in both rich and low-income places. Swedish police do not record or release the ethnicity of convicted criminals, but Linda H Straaf head of intelligence at National Operations Department says they are from poor areas and many are second- or third-generation immigrants.

While Swedish media sometimes are accused of not covering the topic enough, a 2019 study by polling company Kantar Sifo found that law and order was the most covered news topic on Swedish TV and radio and on social media.[63][66]

In 2018, a New York Times article said that gang violence was becoming more frequent, in part because of an increase in weapons flowing over the border with neighboring Denmark.[67]

In 2019, Denmark, worried about the bombings in Sweden, introduced passport controls for the first time since the 1950s.[68]

While gun homicides were on the rise in the 2011-2018 time span, according to a study at Malmö University the number of hand grenade attacks had shown a strong increase in the same period and a total of 116 hand grenade detonations were recorded. The number of hand grenade attacks increased from two in 2011 to 39 in 2016 where the latter was a record year. Of the hand grenade attacks, 28% are directed towards individuals and the remainder towards police stations and other buildings. Two people have been killed and about ten have been injured.[62]

In January 2018, a 63-year-old man was killed when he found a grenade on his way to a supermarket with his wife. Thinking it was a toy, he picked it up and was killed when it detonated. In 2016 an 8-year-old boy was killed when a hand grenade was thrown into an apartment in Biskopsgården as part of crime gang warfare.[62]

Criminologists in Sweden don't know why there was a strong increase and why Sweden has a much higher rate than countries close by.[62]

Sex crimes

editGraphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

A long-standing tradition of gender equality policy and legislation, as well as an established women's movement, have led to several legislative changes and amendments, greatly expanding the sex crime legislation.[70][71] For example, in 1965 Sweden was one of the first countries in the world to criminalise marital rape,[71] and Sweden is one of a few countries in the world to criminalize only the purchase of sexual services, but not the selling.[72]

The rate of exposure to sexual offences has remained relatively unchanged, according to the SCS, since the first survey was conducted in 2006, despite an increase in the number of reported sex crimes.[73] This discrepancy can largely be explained by reforms in sex crime legislation, widening of the definition of rape,[74][75][76] and an effort by the Government to decrease the number of unreported cases.[75][77][78][79] In SCS 2013, 0.8 percent of respondents state that they were the victims of sexual offences, including rape; or an estimated 62,000 people of the general population (aged 16–79). Of these, 16 percent described the sexual offence as "rape" — which would mean approximately 36,000 incidents of rape in 2012.[73]

According to the 2016 SCS 1.7 percent of persons stated that they had been exposed to a sexual offence. This is an increase of more than 100 percent compared to 2012 and a 70 percent compared to 2014, when 1.0 percent of persons stated exposure. Exposure to sexual offences is significantly more common among women than men, and most common in the 20–24 age bracket. Sexual offences are most common in a public place and in most cases the perpetrator is unknown to the victim.[26]: 5–8

A frequently cited source when comparing Swedish rape statistics internationally is the regularly published report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) — although they discourage this practice.[80] In 2012, according to the report by UNODC, Sweden was quoted as having 66.5 cases of reported rapes per 100,000 population,[80] based on official statistics by Brå.[81][Note 1] The high number of reported rapes in Sweden can partly be explained by differing legal systems, offence definitions, terminological variations, recording practices and statistical conventions, making any cross-national comparison on rape statistics difficult.[82][Note 1]

According to a 2014 study published by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), approximately one third of all women in the EU were said to have suffered physical and/or sexual abuse. At the top end was Denmark (52%), Finland (47%) and Sweden (46%).[83][84] Every second woman in the EU has experienced sexual harassment at least once since the age of 15. In Sweden that figure was 81 percent, closely followed by Denmark (80%) and France (75%). Included in the definition of "sexual harassment" was — among other things — inappropriate staring or leering and cyber harassment.[85][86] The report concluded that there's a strong correlation between higher levels of gender equality and disclosure of sexual violence.[87]

In its 2018 report, Nationella trygghetsundersökningen 2018 (tr: "national survey of safety 2018") the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention stated that there had been an increase in the self-reported number of victims of sexual crime from 4.7% in 2016 to 6.4% in 2017. In the 5 preceding years there were escalating levels compared to the 2005–2012 period where the level was relatively stable. The increase in self-reported victimization was greater among women than among men, while the number of male victims remained largely constant over the timespan (see graph). The questionnaire polls for incidents which would equate to attempted sexual assault or rape according to Swedish law.[88]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

In August 2018, SVT reported that rape statistics in Sweden show that 58% of men convicted of rape and attempted rape over the past five years were immigrants born outside of the European Union: Southern Africans, Northern Africans, Arabs, Middle Easterns, and Afghans.[89][90] Swedish Television's investigating journalists found that in cases where the victims didn't know the attackers, the proportion of foreign-born sex offenders was more than 80%.[90] The number of rapes reported to the authorities in Sweden significantly increased[91] by 10% in 2017,[92][93] according to latest preliminary figures from the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention.[92][93] The number of reported rape cases was 73 per 100,000 citizens in 2017, up 24% in the past decade.[93] Official numbers show that the incidence of sexual offences is on the rise;[90][91][93] the Government has declared that young women are facing the greatest risks and that most of the cases go unreported.[91]

Robbery

editThe rate of exposure to muggings has remained relatively unchanged since 2005, according to the SCS, with 0.9 per cent of respondents stating they were the victim of such a crime in 2015.[25] There were 99 robberies recorded by police per 100,000 population in 2015.[26]: 5–8 [94][Note 1] The prevalence victimisation rates for robbery was slightly above the EU-average in 2004, and lower than countries such as Ireland, Estonia, Greece, Spain, the United Kingdom and Poland.[43]

Starting in 2015, there was a rising trend in robberies where self-reported victimisation rate rose to close to around 1.5 per cent in 2019 among people aged 16–84.[95]

Adolescent victims

editA study published in 2000 by Brå on adolescent robberies in Stockholm and Malmö found that muggings had increased in the 90s, with approximately 10 per cent of the boys and 5 per cent of the girls aged 15–17 having been the target of a mugging. Desirable objects are mainly money and cell phones, with an average value of around SEK 800. Only half of the crime was reported to the police, and foreign-born youths were overrepresented in the offenders demographic.[96] Follow-up studies have shown the level remaining unchanged between 1995 and 2005.[97]

Harassment

editThe percentage of persons exposed to harassment in 2015 was 4.7 per cent. This is an increase as compared with 2014, when 4.0 per cent stated that they had been exposed. Between 2005 and 2010, the percentage of exposed persons gradually declined from 5.2 per cent to 3.5 per cent. Thereafter, the percentage increased between 2011 and 2015 towards the same level as when the survey was commenced (when the percentage of exposed persons was 5.0%). Exposure to harassment is more common for women than men, and most common among the youngest in the survey (in the 16–19 age bracket). It is most common for the perpetrator to be unknown to the victim.[26]: 5–8

There might be a correlation between rise in harassment by an unknown perpetrator due to the general rise of harassment in various online communities, but nothing conclusive. Most harassment reported is either women harassing women or men harassing men, the smallest portion of reported cases are men harassing women.[98]

Property offences

editGraphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

The SCS indicate that 9.2 per cent of households fell victim to some type of domestic property offence, which is a reduction since 2006 (when the percentage was 12.6). Crimes in this group includes theft, theft from a vehicle, bicycle theft or residential burglary. Around half of the domestic property offences reported in the SCS 2013 are stated as having been reported to the police, and the overwhelming majority of crime victims state that this happened only once in 2012.[13]

Theft of personal property and pickpocketing are among the lowest in Europe, as is car theft and theft from a car.[43]

Burglary

editSweden had the lowest prevalence victimisation rate for burglary in Europe, according to the 2005 EU ICS,[43] and the rate of exposure to residential burglary has remained relatively unchanged since 2006.[25] In SCS 2013, 0.9 percent of households stated that they were the victims of burglary in 2012.[25] Sweden had 785 cases of reported burglary per 100,000 population in 2012, which is a reduction from the previous year by 6 percent.[94][needs update][Note 1] The majority of burglaries in Sweden are committed by international gangs from Eastern European countries like the Balkans, Romania, Poland, the Baltic countries, and Georgia.[100] The total number of burglaries in southern Sweden were 5871 in 2015 and 4802, the reduction was attributed to border checks introduced in November 2015 due to the ongoing European migrant crisis and police having manage to catch a number of gangs in 2016. The third reason for the reduction was community cooperation.[101]

Burglary perpetrators

editSince Police in Sweden have a low conviction rate for burglaries, there is also corresponding ignorance about who the burglars are.[102]

The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention received responsibility for compiling statistics in 1994, at which time the two main categories of offenders were youth and drug addicts.[citation needed] This pattern changed into one where the main category of offenders were organised gangs, some of which were composed of foreigners travelling to Sweden in order to commit crime and then return to their home countries again.[citation needed] In the Stockholm area police estimated in 2014 that a third of all burglaries were done by foreign nationals.[102] In 2015 police were reported as estimating that foreign gangs comprising 1500 individuals were organized with some members living Sweden to coordinate thefts: a third of these gangs are from Lithuania, a fifth from Poland and the rest from Georgia, Belarus, Romania and Bulgaria.[103] In 2017 police were reported as estimating that about half of the annual 20,000 burglaries, including failed attempts, were committed by gangs from the Balkans, Romania, the Baltic states and Georgia.[104]

Fear of violence

editAccording to a survey by the Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society (MUCF), performed in 2018, and released in April 2019, 70% of men and 36% of women in the ages 16–29 years old were afraid of being subjected to violence when they are outside. In 2013 the percentages were 26% for men and 32% for women.[105][106][107]

According to the 2017 EU-SILC survey, Sweden was one of the countries in Europe where the highest share of the population experience problems with crime, violence or vandalism in the area they live.[108]

Criminal sanctions

editSanctions under the Swedish Penal Code consist of fines and damages, imprisonment, conditional sentences, probation, being placed in special care and community service. Various sanctions can be combined. A basic premise in the Penal Code is that non-custodial penalties are more desirable than custodial, and the court has considerable latitude when choosing a criminal sanctions, paying special attention to measures chiefly aimed at rehabilitating offenders.[109][110]

Fines and damages

editA person who has committed a crime may be ordered to pay damages to the victim. Such damages can relate to compensation for destroyed clothing, a broken tooth, costs for medical care, pain and suffering, or personal violation.[111] A person sentenced for an offence that could lead to imprisonment must pay SEK 800 to the Crime Victim Fund.[112] Fines are determined in money, or as day fines. In the case of day fines, two figures are given, for example "40 day fines of SEK 50" (i.e. SEK 2,000). The first figure shows how serious the court has considered the offence and the latter figure depends on the financial situation of the accused.[110][113]

Conditional sentences, probation and community service

editConditional sentences are primarily intended when a person commits a one-off crime and there is no reason to fear that he or she will re-offend. Probation can be applied to crimes for which fines are considered insufficient. Like a conditional sentence, it is non-custodial, but it is relatively intrusive.[110]

If a conditional sentence is imposed there will be a probationary period of two years. During this period, the person must conduct himself in an acceptable manner. The conditional sentence may be combined with day fines and/or an obligation to perform community service. There is no check made as to whether the person sentenced has conducted himself in an acceptable manner; but if the person is found to conduct himself in an unacceptable manner, the court may issue a warning, change a provision, or decide that the conditional sentence should be replaced by another sanction.[114]

A person who has been sentenced to probation is subject to a probationary period of three years. During this period, the person must conduct himself in an acceptable manner. A probation officer is appointed, who will assist and support the person sentenced. The court may specify rules about medical care, work and housing during the probationary period. The probation may be combined with day fines, imprisonment, an obligation to undergo care according to a predetermined treatment plan and/or to perform community service.[115]

Community service is an obligation to perform certain unpaid work during a particular time. A person sentenced to community service serves his sentence through working, for example, for an association or a not-for-profit organisation.[116]

Prison and electronic monitoring

editA person who has been sentenced to at most six months imprisonment has the opportunity to serve the sentence in the form of intensive supervision with electronic monitoring. The person sentenced will serve the penalty at home and may only leave home at certain times, for example, to go to work. Compliance with these times is checked electronically.[117]

A person who has been sentenced to prison will receive an order from the Swedish Prison and Probation Service to attend an institution. It is possible to start serving the penalty immediately after the judgement has been made, and in certain cases, the person sentenced can get a postponement up to one year. A sentence of imprisonment can, in certain cases, be enforced by the Prison and Probation Service with the use of an ankle monitor outside the institution.[118]

Prison sentences may not be less than 14 days and may not exceed ten years (18 years for some offences) or life imprisonment. A person sentenced to life imprisonment can apply for a determined sentence at the Örebro Lower Court. A prisoner has to serve at least 10 years in prison before applying and the set sentence cannot be under 18 years. However, some prisoners may never be released, being considered too dangerous.[110]

Young offenders

editAccording to the Penal Code, persons under 15 who have committed a crime cannot be sentenced to any sanction. If the under age offender is in need of corrective measures due to the crime, it is the responsibility of the National Board of Health and Welfare to rectify the situation, either by ordering that he be put into care in a family home or a home with special supervision.[110]

As a rule, offenders between 15 and 17 are subject to sanctions under the Act on Special Rules for the Care of the Young (SFS 1980:621) instead of normal criminal sanctions. An offender aged 15 and 17 years old, who have committed serious or repeated crimes, and is sentenced to prison or closed juvenile care usually serves time in a special youth home run by the National Board of Institutional Care. A person under 18 years is only sentenced to prison during exceptional circumstances. In less serious cases, fines are levied.[110]

For offenders between 18 and 19 years of age, measures in accordance with the Act on Special Rules for the Care may only be used to a limited extent. A person over 18 but under 21 can be sentenced to prison only if there are special reasons for this, with regard to the crime, or for other special reasons. A person who is under 21 when a crime was committed may receive milder sentencing than that normally stipulated, and may never be sentenced to life imprisonment if the crime was committed before Jan 2 2022.[110]

There are no age limits for the application of conditional sentences.[110]

Incarceration rate

editSweden had an incarceration rate of 66 persons per 100,000 inhabitants in 2013,[119] which is significantly lower than in most other countries.[Note 3] By comparison, the EU average incarceration rate in the period 2008–2010 was 126 persons per 100,000.[120][121]

In 2012, approximately 12,000 prison terms were handed down—a level comparable to the one in the mid-1970s. The number of people sentenced to prison went down in the nine-year period of 2004–2013, but the average sentence length (approximately 8.4 months) has not been affected.[122][123]

Image in media

editThere has been debate in the media about the crime rate in Sweden, and further debate about how crime has been affected by the accumulated immigration and refugee influx. Some international media have claimed that the refuge immigrants in Sweden created dangerous neighborhoods that are now "no-go zones" for Swedish police.[124] Several pieces by Norsk rikskringkasting, the state-run media channel in the neighboring country Norway have described the "no-go zones" as areas in which ambulances, the fire brigade and police are routinely attacked, with reporter Anders Magnus in 2016 threatened and hurled rocks at by masked men when he tried to make interviews in Husby.[125][126][127] Norwegian minister of immigration and integration Sylvi Listhaug and opposition politician Bård Vegard Solhjell said that they were "shocked" by the emergence of no-go zones in Sweden.[128]

Another incidence of foreign journalists attacked in a Stockholm suburb includes the Australian team of Liz Hayes from CBS's 60 minutes in Rinkeby in 2016, working with anti-immigration activist Jan Sjunnesson,[129][130] in which a member of the crew was allegedly dragged into a building during filming and punched and kicked by several people.[131] In 2017, independent investigative journalist Tim Pool was escorted out of Rinkeby by police, "as many men were getting agitated by our presence".[citation needed] However, Swedish police authorities claimed that Pool was not formally escorted out of the area, as no police report on the incident was filed.[132] After his visit to Sweden, Pool concluded that Sweden "has real problems".[citation needed]

Swedish-Kurdish economist Tino Sanandaji said that, due to fear of being perceived as racists, it has been taboo in Sweden to describe the situation in vulnerables areas due to their having a high fraction of immigrants.[125]

In February 2017, UKIP British politician Nigel Farage defined the Swedish city of Malmö as the "rape capital of Europe",[133] and linked a high number of rapes in Sweden to the immigrants and asylum seekers from Africa and the Middle East;[133] he was subsequently criticized by the BBC because, at the time, there were no data available on the ethnicity of the attackers.[133]

In November 2020, Swedish crime trends were used as an example not to follow by the Finns Party who claimed both Sweden and Finland's problem with youth crime were the result of failed immigration policies. Interior minister Maria Ohisalo instead maintained that the problems were due to "inequality".[134]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Statistics database". statistik.bra.se. Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "The Swedish Penal Code" (PDF). Government of Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Law 1994:458". Lagen.nu.

- ^ a b "Rapport 2008:23 - Brottsutvecklingen i sverige fram till år 2007" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. pp. 38, 41. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

I Sverige har den registrerade brottsligheten precis som i övriga västvärlden ökat kraftigt under efterkrigstiden. [...] Vid mitten av 1960-talet införde Polisen nya rutiner av statistikföring en vilket har framförts som en delförklaring till den kraftiga ökningen, i synnerhet i början av denna period (Brå 2004). [...] Detta beror sannolikt främst på att toleransen mot vålds- och sexualbrott har minskat i samhället. Att man i samhället tar våld på större allvar demonstreras inte minst genom att synen på olika våldshandlingar skärpts i lagstiftningen (ibid. samt kapitlet Sexualbrott)

- ^ a b c "Trials in criminal cases". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Von Hofer, Hanns (2000). "Crime Statistics as Constructs: The Case of Swedish Rape Statistics". European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. 8 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1023/A:1008713631586. S2CID 195221128.

- ^ a b c d e f Våldsbrottsligheten: Ökande, minskande eller konstant? Ett diskussionsunderlag (in Swedish). Malmö University. 2007. ISBN 978-91-7104-207-1. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Duty to prosecute". The Swedish Prosecution Authority. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "The Swedish Prosecution Authority". The Swedish Prosecution Authority. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Suspect". The Swedish Prosecution Authority. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Summary punishment". The Swedish Prosecution Authority. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Appealing a criminal case". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Swedish Crime Survey 2013" (PDF). Brå. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Motståndskraft, oberoende, integritet – kan det svenska samhället stå emot korruption?" (PDF). Transparency International Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "Snapshot of the Sweden Country Profile". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. GAN Integrity Solutions. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ Ekerlid, Erik (22 April 2021). "Rekord i svensk korruption – "Kan fiffla helt straffritt"". Tidningen Näringslivet (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 May 2024.

Mutor, riggade affärer och obstruktion av offentliga handlingar. Korruptionen i svenska myndigheter och kommuner blir allt värre, konstaterar Olle Lundin, professor i förvaltningsrätt och expert på korruption. "Respekten de senaste tio åren har verkligen försämrats", säger han till TN.

- ^ "Korruptionsgranskare om Sverige: Fortsatt negativ utveckling". Europaportalen (in Swedish). 30 January 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

Den fortsatt negativa utvecklingen kräver nu att regeringen tar ett samlat och systematiskt grepp kring arbetet mot korruption i Sverige, sade Ulrik Åshuvud i ett uttalande. Den negativa svenska utvecklingen har pågått sedan 2015.

- ^ "Sverige allt mer korrupt". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). 30 January 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "Korruptionen ökar i Sverige". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). 30 January 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Roslund, Jonas (12 December 2016). "Risk att korruption underskattas i Sverige". Linköpings universitet (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "Tabell 1.2. Anmälda brott per 100 000 av medelfolkmängden, åren 1950–2016". BRÅ. 2017.

- ^ "About Brå". The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Rapport 2008:23 - Brottsutvecklingen i sverige fram till år 2007" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. p. 61. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

Den stora ökningen av antalet anmälda brott sedan början 1990-talet förklaras i huvudsak av det anmälningssystem som polisen då införde

- ^ Nyheter, SVT. "Krav på att Brå tar fram statistik över brott och ursprung". svt.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The Swedish Crime Survey 2013 - English summary of Brå report 2014:1" (PDF). The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. pp. 5, 7. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Command, Carl; Hambrook, Emelie; Wallin, Sanna; Westerberg, Sara; Stri, Åsa Irlander; Hvitfeld, Thomas (2017). "Swedish Crime Survey 2016 - English summary of 2016 Brå report 2017:1" (PDF). The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. 2017 (2). Stockholm: Brottsförebyggande rådet (Brå). ISSN 1100-6676. URN:NBN:SE:BRA-697.

- ^ "Swedish Crime Survey". www.bra.se. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Regeringskansliet, Regeringen och (23 February 2017). "Facts about migration and crime in Sweden". Regeringskansliet. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Here are Sweden's crime stats for 2016". Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Rape & Sexual Offences". bra.se. 16 January 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Sexual Offences". Brottsrummet. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Personer lagförda för brott" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. p. 5. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "How gang violence took hold of Sweden – in five charts". The Guardian. 30 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Crime statistics". Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Kodning av brott - Anvisningar och regler" (PDF). Brå. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Sweden's rape rate under the spotlight". BBC News. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Violence and assault". Brå. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Rapport 2008:23 - Brottsutvecklingen i sverige fram till år 2007" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Estrada, Felipe (2005). Våldsutvecklingen i Sverige - En presentation och analys av sjukvårdsdata (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Swedish Institute for Futures Studies. ISBN 978-91-89655-62-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

Nothing in the hospital data indicates an increase in hospital admissions resulting from serious violent incidents [...] Instead the hospital data serve to verify the more stable trends indicated by victim surveys and lethal violence statistics

- ^ "Rapport 2009:16 - Misshandel mellan obekanta" (PDF) (in Swedish). Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b tagesschau.de. "Schwedens Banden-Problem". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Comparative Criminology | Europe - Sweden". Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Van Dijk; et al. (2005). "The Burden of Crime in the EU. Research Report: A Comparative Analysis of the European Crime and Safety Survey (EU ICS) 2005" (PDF). UNICRI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Murder and manslaughter". Brå. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Aftonbladet. "Brå: Allt fler offer för dödligt våld i Sverige". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Konstaterade fall av dödligt våld - En granskning av anmält dödligt våld 2017" (PDF). Brottsförebyggande rådet.

- ^ "Kriminalstatistik 2015" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ "Kriminalstatistik 2016 Konstaterade fall av dödligt våld" (PDF). Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ "Mord och dråp - Brå". www.bra.se. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Var tionde mord förra året var hedersmord". Göteborgs-Posten (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "Vanligt med utländsk bakgrund bland unga män som skjuter - DN.SE". DN.SE (in Swedish). 20 May 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Svensk politi skulle ta tilbake kontrollen over lovløse områder. To år senere er situasjonen blitt enda verre". Aftenposten. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ "Antalet knivdåd ökar för sjunde året i rad". www.tv4play.se. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Kniv vanligaste mordvapnet". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). 18 July 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Larsson, Jens (8 December 2020). "Rekordmånga kan falla offer för dödligt knivvåld i år". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Wahlgren, Jennie; Botsjö, Markus (2 June 2023). "Kriminologen: Senaste tidens attacker typiska för knivvåldet". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Sturup, Joakim; Rostami, Amir; Mondani, Hernan; Gerell, Manne; Sarnecki, Jerzy; Edling, Christofer (7 May 2018). "Increased Gun Violence Among Young Males in Sweden: a Descriptive National Survey and International Comparison". European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. 25 (4): 365–378. doi:10.1007/s10610-018-9387-0. hdl:2043/25999. ISSN 0928-1371.

- ^ "Dödligt skjutvapenvåld har ökat i Sverige, men inte i övriga Europa - Brottsförebyggande rådet". www.bra.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Polisen: Risken att oskyldiga skjuts till döds har ökat". Metro (in Swedish). Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "Justitieministern: Liten risk att oskyldiga drabbas". Expressen TV (in Swedish). 23 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Frenker, Clarence (29 December 2020). "Ny högstanivå för antalet skjutningar i Sverige 2020". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d Salihu, Diamant (10 December 2018). "116 granatattacker på åtta år – Sverige sticker ut". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Maddy Savage (12 November 2019). "Sweden's 100 explosions this year: What's going on?". BBC. Stockholm.

- ^ "Förtydligande om internationell jämförelse av handgranatsdetonationer". Kriminologiska funderingar blog (in Swedish). 11 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Johannes Ledel (8 November 2019). "Swedish police chief: No international equivalent to Sweden's wave of bombings". The Local.

- ^ Jon Henley (4 November 2019). "Sweden bomb attacks reach unprecedented level as gangs feud". The Guardian.

- ^ Anderson, Ellen Barry and Christina (3 March 2018). "Hand Grenades and Gang Violence Rattle Sweden's Middle Class". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Martin Selsoe Sorensen (13 November 2019). "Denmark, Worried About Bombings by Swedish Gangs, Begins Border Checks". The New York Times. Denmark.

- ^ "Nationella trygghetsundersökningen 2018 / Tabell 1 pdf page 7". bra.se Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. 16 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Nordlander, Jenny (10 June 2010). "Fler brott bedöms som våldtäkt". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ a b Kelly, Liz; Lovett, Jo; Burman, Michele (May 2009). Different systems, similar outcomes? Tracking attrition in reported rape cases in eleven European countries (Country briefing: Scotland). London: Child and Woman Abuse Studies Unit (CWASU), London Metropolitan University. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2015. ISBN 9780954480394 Pdf. Final report, pdf. Funded by the European Commission Daphne II Programme.

- ^ "Lagrådsremiss - En ny sexualbrottslagstiftning" (PDF) (in Swedish). Government of Sweden. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2004. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ a b Nationella trygghetsundersökningen 2013 - Om utsatthet, otrygghet och förtroende (Rapport 2014:1) (PDF) (in Swedish). Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. 2014. pp. 35–36, 47–48. ISBN 978-91-87335-20-4. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Petter Asp, Professor of Criminal Law (May 2010). "Sju perspektiv på våldtäkt". Nationellt centrum för kvinnofrid/Uppsala University. pp. 24, 59. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ a b Ruth, Alexander (14 September 2012). "Sweden's rape rate under the spotlight". BBC News. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "How common is rape in Sweden compared to other European countries?". The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. 18 January 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Nya metoder ska ge fler våldtäktsåtal". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 25 November 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "Kunskapsbank - Nationellt Centrum för Kvinnofrid" (in Swedish). Uppsala University. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

Insatserna från Rikspolisstyrelsen består bland annat av utbildning, informationsspridning och andra åtgärder för att förstärka Polisens förmåga upptäcka och utreda dessa brott. En annan målsättning är att allmänhetens förtroende för Polisen ska stärkas, så att fler brott anmäls.

- ^ Jo Lovett; Liz Kelly (2009). Different systems, similar outcomes?. London Metropolitan University. pp. 9, 95, 105. ISBN 978-0-9544803-9-4.

In Sweden, reforms in 2005, which re-defined the sexual exploitation of a person in a helpless state as rape, also coincided with a marked increase in reports. [...] An expert centre for the care of battered and raped women was established, with government funding, at Uppsala University Hospital in 1995. The legal definition of rape in Sweden has been successively broadened over the last two or more decades. [...] Sweden [has] trained male and female officers in most areas

- ^ a b "Rape at the national level, number of police-recorded offences". UNODC. 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

Please note that when using the figures, any cross-national comparisons should be conducted with caution because of the differences that exist between the legal definitions of offences in countries, or the different methods of offence counting and recording.

- ^ "Anmälda brott, totalt och per 100 000 av medelfolkmängden, efter brottstyp och månad för anmälan, år 2012 samt jämförelse med föregående år". Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Jo Lovett; Liz Kelly (2009). Different systems, similar outcomes?. London Metropolitan University. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-9544803-9-4.

- ^ "A third of women in EU have suffered 'sexual violence'". France 24 with AP & AFP. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Violence against women: an EU-wide survey" (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. pp. 28–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Ann Törnkvist (ann.tornkvist@thelocal.com). "Sweden stands out in domestic violence study - The Local". Thelocal.se. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Violence against women: an EU-wide survey, Sexual harassment" (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. p. 95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Violence against women: an EU-wide survey" (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. p. 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

Increased gender equality leads to higher levels of disclosure about violence against women

- ^ "Nationella trygghetsundersökningen 2018" (in Swedish). BRÅ. 20 November 2018.

- ^ a b Nyheter, SVT (22 August 2018). "Ny kartläggning av våldtäktsdomar: 58 procent av de dömda födda utomlands". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Swedish Television/Uppdrag Granskning. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "Sweden rape: Most convicted attackers foreign-born, says TV". BBC News. London. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "Sweden approves new law recognising sex without consent as rape". BBC News. London. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b Roden, Lee (18 January 2018). "Reported rapes in Sweden up by 10 percent". Sveriges Radio. Stockholm. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d Billner, Amanda; Niklas, Magnusson (28 March 2018). "Surge in Rape Cases Puts Focus on Crime Ahead of Swedish Election". Bloomberg News. Stockholm. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Kriminalstatistik 2012" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Start / Statistik / Statistik utifrån brottstyper / Rån". bra.se. 18 October 2021. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Ungdomar som rånar ungdomar i Malmö och Stockholm" (PDF) (in Swedish). Brå. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Nya mönster bland unga kriminella" (in Swedish). Brå. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Online Harassment". Online Harassment. 2014 – via Pew Research Center.

- ^ "MSB.se Statistikdatabasen -> Räddningstjänstens insatser -> Bränder i fordon". ida.msb.se. Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Kraftig minskning av bostadsinbrott – internationella ligor skräms bort av gränskontrollerna". Hd.se. 30 January 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Kraftig minskning av bostadsinbrott – internationella ligor skräms bort av gränskontrollerna". Sydsvenskan (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ a b "(sv) Därför kommer inbrotten med höstmörkret". No. 1–2014. Magasinet Neo. 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Nyheter, SVT. "1.500 personer ur utländska inbrottsligor kartlagda av svensk polis". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "Kraftig minskning av bostadsinbrott – internationella ligor skräms bort av gränskontrollerna". Sydsvenskan (in Swedish). Sydsvenskan. 30 January 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Unga med attityd 2019, del 1". mucf.se Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society. 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Unga med attityd 2013". mucf.se Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society. 5 November 2013.

- ^ Stefansson, Klara (11 May 2019). "Ny studie: Killar dubbelt så oroliga för våld utomhus jämfört med tjejer". SVT Nyheter.

- ^ "Fler upplever brottslighet och vandalisering i sitt bostadsområde". Statistiska Centralbyrån (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "Criminal sanctions". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Swedish system of Sanctions" (PDF). Swedish Prison and Probation Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Damages". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Payment to the Crime Victim Fund". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Fines". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Conditional sentence". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Probation". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Community service and juvenile community service". Supreme Court of Sweden. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Intensive supervision with electronic monitoring (foot tag)". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Prison". Supreme Court of Sweden. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Sweden - World Prison Brief". International Centre for Prison Studies. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "USA - World Prison Brief". International Centre for Prison Studies. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Crime trends in detail". Eurostat. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Allt färre döms till fängelse" (in Swedish). Brå. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Lagföring och kriminalvård – slutlig statistik 2013" (in Swedish). Brå. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "People in Sweden's Alleged "No-Go Zones" Talk About What it's Like to Live There". Vice. 16 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Svensk politi: – Vi er i ferd med å miste kontrollen". Nrk.no. 8 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "NRK-team truet og kastet stein etter i Sverige". Nrk.no. 6 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Kastet stein på Anders Magnus og NRK-kollega i Rinkeby". Journalisten.no. 6 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Listhaug: – Sjokkert over tilstandene i Sverige". Nrk.no. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Här sprider Jan Sjunnesson en falsk story i australiensisk tv". Resume.se. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Chefredaktör på SD-ägd tidning sprider grov rasism". Expo.se. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Video Released of 60 Minutes Film Crew Being Attacked in Sweden by Migrants". Mediaite.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Police dispute US journalist's claim he was escorted out of Rinkeby". Thelocal.se. 1 March 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "Reality Check: Is Malmo the 'rape capital' of Europe?". BBC News. London. 24 February 2017.

- ^ Radio, Sveriges (18 November 2020). "Svensk brottslighet används som skräckexempel i Finland - Nyheter (Ekot)". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). Retrieved 21 November 2020.

External links

edit- The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention official site (In English, also available in a number of other languages.)

- The Local: How did reported crime rates change? (2019)