Proposed expansion of the New York City Subway

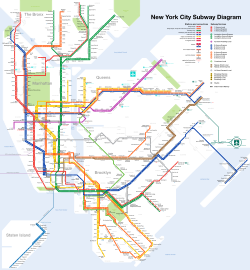

Since the opening of the original New York City Subway line in 1904, and throughout the subway's history, various official and planning agencies have proposed numerous extensions to the subway system. The first major expansion of the subway system was the Dual Contracts, a set of agreements between the City of New York and the IRT and the BRT. The system was expanded into the outer reaches of the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens, and it provided for the construction of important lines in Manhattan. This one expansion of the system provided for a majority of today's system.

Even with this expansion, there was a pressing need for growth. In 1922, Mayor John Hylan put out his plan for over 100 miles of new subway lines going to all five boroughs. His plan was intended to directly compete with the two private subway operators, the IRT and the BMT. This plan was never furthered. The next big plan, and arguably the most ambitious in the subway system's history, was the "Second System". The 1929 plan by the Independent Subway to construct new subway lines, the Second System would take over existing subway lines and railroad rights-of-way. This plan would have expanded service throughout the city with 100 miles of subway lines. A major component of the plan was the construction of the Second Avenue Subway. The Stock Market Crash of 1929 put a halt to the plan, however, and subway expansion was limited to lines already under construction by the IND.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the plans were revised, with new plans such as a line to Staten Island and a revised line to the Rockaways. In the late 1940s and 1950s, a Queens Bypass line via the Long Island Rail Road's Main Line was first proposed as a branch of the still-planned Second Avenue Subway. In addition, capacity on existing lines became improved through the construction of strategic connections such as the Culver Ramp, the 60th Street Tunnel Connection, and the Chrystie Street Connection, and through the rebuilding of DeKalb Avenue Junction. These improvements were the only things to come out of these plans. Eventually, these plans were modified to what became the Program for Action, which was put forth by the New York City Transit Authority in 1968. This was the last plan for a major expansion of the subway system. The plan included the construction of the Second Avenue Subway, a Queens Bypass line, a line replacing the Third Avenue El in the Bronx, and other extensions in the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn. While ambitious, very little of the plan was completed, mostly because of the financial crisis in the 1970s.

Until the 1990s, there was little focus on expansion of the system because the system was in a state of disrepair, and funds were allocated to maintaining the existing system. In the 1990s, however, with the system in better shape, the construction of the Second Avenue Subway was looked into again. Construction of the Second Avenue Subway started in 2007, and the first phase was completed in 2017. Since the 1990s, public officials and organizations such as the Regional Plan Association have pushed for the further expansion of the system. Projects such as the TriboroRx, a circumferential line connecting the outer boroughs, the reuse of the Rockaway Beach Branch, and the further expansion of the Second Avenue Subway have all been proposed, albeit mostly unfunded.

Triborough System

editThe Triborough System was a proclamation for new subway lines to the Bronx and Brooklyn. The new lines include the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, IRT Pelham Line, and IRT Jerome Avenue Line. The Manhattan Bridge line described below later became the BMT West End Line, BMT Fourth Avenue Line, the BMT Sea Beach Line, and the Nassau Street loops.[1][2]

The route of the new subway ... comprises a main trunk north and south through Manhattan Borough on Lexington Avenue and Irving Place from the Harlem River to Tenth St. and on Broadway, Vesey and Church Sts. from Tenth St. to the Battery; two branches in Bronx Borough, one northeast via 138th St. Southern Boulevard and Westchester Ave. to Pelham Bay Park. the other northerly via River Ave. and Jerome Ave. to Woodlawn Road, connecting with the Manhattan trunk by a tunnel under the Harlem River; a Manhattan-Brooklyn line extending from the North River via Canal Street across the East River on the Manhattan Bridge to connect with the Fourth Avenue subway in Brooklyn now being built, which thus becomes an integral part of the larger system; two branches southerly from the Fourth Ave. line extending south to Fort Hamilton and southeast to Coney Island; and a loop feeder line in Brooklyn through Lafayette Ave. and Broadway, connecting with the Fourth Ave. line at one end. and at the other crossing the Williamsburg Bridge and entering the Centre Street Loop subway in Manhattan which is thus also incorporated in the system.

In 1911, William Gibbs McAdoo, who operated a competing subway company called the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad, proposed building a line under Broadway between Hudson Terminal and Herald Square.[3] He later proposed that the Broadway line be tied into the IRT's original subway line in Lower Manhattan. The Broadway line, going southbound, would merge with the local tracks of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line in the southbound direction at 10th Street. A spur off the Lexington Avenue Line in Lower Manhattan, in the back of Trinity Church, would split eastward under Wall Street, cross the East River to Brooklyn, then head down the Fourth Avenue Line in Brooklyn, with another spur underneath Lafayette Avenue.[4]

The Triborough System later became part of the Dual Contracts, signed on March 19, 1913 and also known as the Dual Subway System. These were contracts for the construction and/or rehabilitation and operation of rapid transit lines in New York City. The contracts were "dual", in that they were signed between the City and the IRT and Municipal Railway Company, a subsidiary of the BRT (later BMT).[5]

Some lines proposed under the Contracts were not built, most notably an IRT line to Marine Park, Brooklyn (at what is now Kings Plaza) under either Utica Avenue, using a brand-new line, or Nostrand Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, using the then-new IRT Nostrand Avenue Line. There were also alternate plans for the Nostrand Avenue Line to continue down Nostrand Avenue to Sheepshead Bay.[6]

Mayor Hylan's plan

editOn August 28, 1922, Mayor John Francis Hylan unveiled his own plans for the subway system, which was relatively small at the time. His plan included building over 100 miles (160 km) of new lines and taking over nearly 100 miles (160 km) of existing lines. By the end of 1925, all of these routes were to have been completed. The lines were designed to compete with the IRT and BMT.[7][8]

Hylan's plan contained the following lines:[9]

- A line running along Manhattan's West Side, stretching from the edge of the city at Yonkers to 14th Street. It would be a two-track line south to Dyckman Street, a three-track line to 162nd Street, and then-on it would be a four-track line. The line would have two southern branches that would diverge at 14th Street. A connection to the BMT Canarsie Line would use a pair of the tracks, while the other pair would go to Atlantic Avenue and Hicks Street in Brooklyn through an East River tunnel. Then it would turn down to Red Hook. There would also be a loop at Battery Park. Another branch would be built; it would consist of two tracks, and would go between 162nd Street and 190th Street via Amsterdam Avenue.

- A First Avenue line, consisting of four tracks, would stretch from the Harlem River to City Hall. At 10th Street, the line would cease to be a four-track line, with the line splitting into two branches. One branch would run to a loop near City Hall, while the other would go to a new Lafayette Avenue line in Brooklyn, running via Third Avenue and the Bowery. On the northern end, at 161st Street, the line would split into two 3-track lines. One of the lines would go to Southern Boulevard and Fordham Road; the other would continue to 241st Street after merging with the existing IRT White Plains Road Line at Fordham Road and Webster Avenue.

- A line from Astoria, Queens, likely connecting to the BMT Astoria Line, across the East River and via 125th Street (near today's Henry Hudson Parkway).

- A line running from Hunters Point in Queens heading southeast to Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn. The line would consist of between two and four tracks, and at Lafayette Avenue, the line would split. Two of them would continue as a Lafayette Avenue, but would then become four tracks. The remaining two tracks would run to Franklin and Flatbush Avenues.

- A new 4-track trunk line along Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn from Borough Hall to Bedford Avenue. The line would narrow to three tracks to Broadway. Then the line would have continued underneath the BMT Jamaica Line to 168th Street. By running underneath the Jamaica Line, the line would directly compete with the BMT. A two-track connection would also be provided to a First Avenue line.

- A new line running under Utica Avenue to Flatlands Avenue. The line would be a branch of the IRT Eastern Parkway Line.[10]: 120

- A four-track Flatbush Avenue line to Emmons Avenue in Sheepshead Bay, before turning west to Surf Avenue in Coney Island via Emmons Avenue. Service to Floyd Bennett Field would be provided with a branch via Flatbush Avenue.

- The BMT Canarsie Line would be extended past 121st Street in Queens to the BMT Jamaica Line.

- A new line, which would run from 90th Street to Prospect Avenue, that would go via Fort Hamilton Parkway and 10th Avenue would be used by BMT Culver Line trains.

- Extension of the BMT Fourth Avenue Line in Brooklyn, south to Bay Ridge–95th Street.

- Extension of the BMT Fourth Avenue Line east to the Fort Hamilton Parkway Line and the BMT West End Line.

- A two-track line from the BMT Fourth Avenue Line at 67th Street to Staten Island via the Staten Island Tunnel.[10]: 120–125

- Extension of the IRT New Lots Line from New Lots Avenue to Lefferts Boulevard.

- The IRT Flushing Line would be extended eastward to Bell Boulevard in Bayside via Main Street, Kissena Boulevard, and Northern Boulevard.

- At Roosevelt Avenue a branch would be constructed off the IRT Flushing Line to Jamaica.

Only some of Hylan's planned lines were built to completion. Completed lines included:[9][11][12]

- An extension of the Fourth Avenue Line to 95th Street.

- Two major trunk lines in midtown Manhattan, with one running under Eighth Avenue and one under Sixth Avenue, which already had an elevated line.

- A crosstown subway under 53rd Street (connecting with the Eighth and Sixth Avenue subways) running under the East River to Queens Plaza (Long Island City), meeting with a Brooklyn–Queens crosstown line, and continuing under Queens Boulevard and Hillside Avenue to 179th Street, where bus service would converge.

- A subway under the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, diverging from the Eighth Avenue Line in Manhattan at 145th Street and Saint Nicholas Avenue.

Major Phillip Mathews disagreed with the Board of Transportation's plan, and in response, he published a report, on December 24, 1926, titled "Proposed Subway Plan for Subway Relief and Expansion". He said that that congestion would not be addressed for Brooklyn and the Bronx; only the planned Grand Concourse line would alleviate congestion, in this case congestion on the IRT Jerome Avenue Line. There would be little relief on the two lines jointly-operated between the IRT and the BMT. He came up with his own plan. He proposed that the Eighth Avenue Line, through a connection from Fulton or Wall Streets to Chambers Street, be connected to the BMT's lines to Coney Island, with a possible connection at the Manhattan Bridge's south side.[9]

In Manhattan, he proposed a new four-track line running down Third Avenue from City Hall, with connections to the White Plains Road and Pelham Lines in the Bronx. The line would therefore have to be built to IRT clearances. At the line's southern end, a connection would be built to the Eastern Parkway Line near Franklin Avenue via a new set of tubes under the East River. To alleviate congestion on the Queens lines, a new trunk line would run from Eighth Avenue in Manhattan to Jamaica, with transfers to the north–south lines in Manhattan and to Brooklyn Crosstown service. This would later be built as the IND Queens Boulevard Line.[9]

To round out expansion in Manhattan, he proposed that an extension of the BMT Canarsie Line to Eighth Avenue. This was built at a later date. To connect the outer boroughs, a four-track Brooklyn-Queens crosstown line would be designed, with the possibility for future extensions into the Bronx and Staten Island.[9]

Subways to New Jersey

editIn 1926, a loop subway service was planned to be built to New Jersey. The rationale given was:[13]

Principal features of a comprehensive plan for passenger transportation between communities in the nine northern counties of New Jersey and the city of New York are outlined in a report submitted on Jan. 15 to the Legislature of the state by the North Jersey Transit Commission. A preliminary report presented about a year ago was abstracted in Electric Railway Journal for Feb. 7, 1925... The ultimate object of the program recommended is the creation of a new electric railway system comprising 82.6 miles [132.9 km] of route, and the electrification of 399 route-miles [642 km] of railroad now operated by steam. As the first step it is proposed to construct an interstate loop line 17.3 miles [27.8 km] in length connecting with all of the north Jersey commuters' railroads and passing under the Hudson River into New York City by two tunnels, one uptown and one downtown. A new low-level subway through Manhattan would complete the loop. Construction costs of this preliminary project are estimated at $154,000,000, with $40,000,000 additional for equipment. The cost of power facilities is not included in this estimate.[13]

Because it would be utilized in both directions, the capacity of the proposed interstate loop line would be equivalent, it is said, to two 2-track lines or one 4-track line from New Jersey to New York City due to its having two crossings between New Jersey and New York. The loop was said to be able to carry 192,500 passengers per hour, or 4.62 million daily passengers, had it been built. The estimate was based on the operation of 35 trains per hour in each direction, and each train would be eleven cars long and would carry 100 passengers per car. It was to be built as a multi-phase project, wherein the IRT and BMT would work together to build that system to New Jersey. Extensions of the IRT Flushing Line and BMT Canarsie Line were both considered; the Canarsie Line was to be extended to Hoboken near the Palisades, while the Flushing Line was to be extended to Franklin Street between Boulevard and Bergenline Avenues in Union City. Ultimately, the cost was too great, and with the Great Depression, these ideas were quickly shot down.[13]

In 1954, Regional Plan Association advocated for an extension of the BMT Canarsie Line from Eighth Avenue to Jersey City under the Hudson River. The tunnel under the Hudson would have cost $40 million. The extension would have provided access to commuter railroads in New Jersey as most lines converged there, and the lines that didn't would be rerouted to stop there. The RPA also suggested having a parking lot there for access from the Pulaski Skyway and the New Jersey Turnpike. It was suggested that either the New York City Transit Authority, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey or the Bi-State Metropolitan Rapid Transit Commission would do the construction.[14]

In 1963, three major commuter groups in New Jersey made expansion proposals. One of them would have involved an extension of the IRT Flushing Line under the Hudson River with a three-track tunnel and then connect with the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railroad.[15]

In 1986, the Regional Plan Association suggested extending the IRT Flushing Line to New Jersey's Meadowlands Sports Complex.[16]

On November 16, 2010, the plan was revisited yet again, as The New York Times reported that Mayor Michael Bloomberg's administration had been working on a plan to extend the 7 service across the Hudson River to Hoboken and continue to Secaucus Junction in New Jersey, where it would connect with most New Jersey Transit commuter lines. It would offer New Jersey commuters a direct route to Grand Central Terminal on the East Side of Manhattan and connections to most other New York City subway routes. This was being planned as an extension of the already-under construction 7 Subway Extension (see below).[17]

In April 2012, citing budget considerations, the director of the MTA, Joe Lhota, said that it was doubtful the extension would be built in the foreseeable future, suggesting that the Gateway Project was a much more likely solution to congestion at Hudson River crossings.[18] A feasibility study commissioned by the city and released in April 2013 revived hope for the project, however, with Mayor Bloomberg saying "Extending the 7 train to Secaucus is a promising potential solution ... and is deserving of serious consideration."[19][20]

In 2017, a further extension of the 7 train to New Jersey was suggested once again, this time as an alternative to constructing a replacement for the Port Authority Bus Terminal.[21] An alternative would include a new terminal at Secaucus Junction in conjunction with the 7 extension.[22] In February 2018, it was revealed that the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had advertised for consultants to write a feasibility study for such an extension, and that it had received bids from several companies. This extension was being planned along with the Gateway Project and, if built, would be able to accommodate a projected 38% increase in the number of people commuting between the two states. The 18-month study would include input from the Port Authority, the MTA, and NJ Transit.[23] If the New Jersey subway extension were to be constructed, it could complement the Gateway Project, which might become overcrowded by 2040.[24][25]

1929–1939 plans

edit| Borough | Number of route miles |

|---|---|

| Queens | |

| The Bronx | |

| Brooklyn | |

| Manhattan |

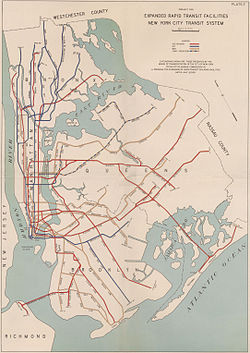

Before unification in 1940, the government of New York City made plans for expanding the subway system, under a plan referred to in contemporary newspaper articles as the IND Second System (due to the fact that most of the expansion was to include new IND lines, as opposed to BMT/IRT lines). The first one, conceived in 1929, was to be part of the city-operated Independent Subway System (IND). By 1939, with unification planned, all three systems were included. Very few of these far-reaching lines were built, though provisions were made for future expansion on lines that intersect the proposals.[26]

The core Manhattan lines of the expansion were the Second Avenue Line (with an extension into the Bronx) and the Worth Street Line, connecting to the Rockaways. The Rockaways were eventually served by the subway via a city takeover of the Long Island Rail Road's Rockaway Beach Branch. A segment of the proposed Second Avenue Subway opened for passenger service in January 2017. The majority of the proposed lines were to be built as elevated subways, likely a cost-cutting measure. The majority of the expansion was to occur in Queens, with the original proposal suggesting 52 miles (84 km) of track be built in Queens alone.[26]

Details

editThe first plan was made on September 15, 1929 (before the IND even opened), and is detailed in the table below.[26] Cost is only for construction, and does not include land acquisition or other items.[27]

| Line | Streets | From | To | Tracks | Route miles | Track miles | Cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manhattan | ||||||||

| East Manhattan trunk line (Second Avenue Line) | Water Street – New Bowery – Chrystie Street | Pine Street | Houston Street | 2 from Pine Street to Chambers Street 4 to Houston Street |

1.34 | 4.68 | $11,300,000 | subway |

| Second Avenue | Houston Street | Harlem River | 4 to 61st Street 6 to 125th Street 4 to Harlem River |

6.55 | 32.84 | $87,600,000 | subway | |

| 61st Street Line | Sixth Avenue – 61st Street | 52nd Street | Second Avenue | 2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | $6,700,000 | subway |

| (Rockaway Line) | Worth Street – East Broadway – Grand Street | Church Street | East River | 2 | 1.95 | 3.9 | $13,300,000 | subway |

| (Utica Avenue Line) | Houston Street | Essex Street | East River | 2 | .93 | 1.86 | $7,900,000 | subway |

| Manhattan subtotal | 11.87 | 45.48 | $126,800,000 | |||||

| Bronx | ||||||||

| Bronx trunk line | Alexander Avenue – Melrose Avenue – Boston Road | Harlem River | West Farms | 4 | 3.97 | 15.88 | $40,400,000 | subway, with a portal between Vyse Avenue and 177th Street, then elevated into the existing IRT White Plains Road Line near 180th Street |

| White Plains Road Line | Morris Park Avenue – Wilson Avenue | Garfield Street | Boston Road | 2 | 3.5 | 7.9 | $13,700,000 | branching off the existing elevated IRT White Plains Road Line, and then going into subway |

| IRT Lafayette Avenue Line | 163rd Street – Hunts Point – Lafayette Avenue – 177th Street | Washington Avenue at Brook Avenue | East Tremont Avenue | 2 | 5.02 | 10.04 | $12,900,000 | subway to near Edgewater Road and Seneca Avenue, then elevated |

| Concourse Line Extension | Burke Avenue – Boston Road | Webster Avenue | Baychester Avenue | 2 | 2.15 | 4.3 | $8,900,000 | extension of the Concourse Line |

| White Plains Road Line | 180th Street | 241st Street | 4.40 | 13.2 | $2,100,000 | owned by IRT, to be taken over ("recaptured") by IND | ||

| Bronx subtotal | 19.04 | 51.32 | $77,000,000 | |||||

| Brooklyn | ||||||||

| Broadway Branch Line (Rockaway Line) | Broadway | East River | Havemeyer Street at South Fourth Street | 2 | 3.16 | 13.5 | $34,800,000 | subway |

| Utica Avenue Line (and Rockaway Line from Havemeyer Street to Stuyvesant Avenue) | Grand Street – South Fourth Street – Beaver Street | East River | Stuyvesant Avenue | 2 to Driggs Avenue 4 to Union Avenue 8 to Bushwick Avenue 4 to Stuyvesant Avenue |

subway | |||

| Stuyvesant Avenue – Utica Avenue | Broadway | Flatbush Avenue | 4 | 5.85 | 23.4 | $39,300,000 | subway to Avenue J, then elevated | |

| Avenue S | Utica Avenue | Nostrand Avenue | 2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | $2,000,000 | elevated | |

| Nostrand Avenue | Avenue S | Voorhies Avenue | 4 | 1.3 | 5.2 | $3,200,000 | elevated | |

| Rockaway Line | Myrtle Avenue | Bushwick Avenue | Palmetto Avenue | 4 | 1.34 | 5.36 | $14,300,000 | subway |

| Fulton Street Line | Liberty Avenue | Fulton Street and Eastern Parkway | Grant Avenue | 4 | 1.84 | 7.36 | $13,500,000 | subway extending the Fulton Street Line to a portal at Liberty Avenue and Crescent Street, then elevated to connect to the BMT Liberty Avenue Line (now part of the Fulton Street Line) at Grant Avenue |

| Nostrand Avenue Extension | Flatbush Avenue | Avenue S | 2 | 2.25 | 4.5 | $7,400,000 | Extension of Nostrand Avenue Line as subway to Kings Highway, then elevated | |

| Brooklyn subtotal | 16.84 | 61.52 | $114,500,000 | |||||

| Queens | ||||||||

| Rockaway Line | Myrtle Avenue – Central Avenue | Palmetto Avenue | 78th Street | 4 | 2.1 | 8.4 | $17,300,000 | subway to Central Avenue near 73rd Place, then along the surface or elevated |

| 98th Street – 99th Street – Hawtree Street | 78th Street | Hammels Station | 4 to Howard Beach 2 to Hammels |

9.2 | 26.2 | $20,200,000 | along the surface or elevated | |

| Rockaway Beach Boulevard | Beach 116th Street | Mott Avenue | 2 | 5.0 | 10.0 | $7,400,000 | along the surface or elevated | |

| Newport Avenue Line (Rockaway Line Extension) |

Newport Avenue | Beach 116th Street | Beach 149th Street | 2 | 1.6 | 3.2 | $2,400,000 | along the surface or elevated |

| Winfield Spur | Garfield Avenue – 65th Place – Fresh Pond Road | Broadway and 78th Street | Central Avenue | 2 | 3.34 | 6.68 | $10,100,000 | subway to 45th Avenue, then elevated to Fresh Pond Road, then subway; terminal station partially-built as part of Roosevelt Avenue-Jackson Heights station, with short trackways leading to the spur. |

| Brinckerhoff - Hollis Avenue Line (Fulton Street Line Extension) |

Liberty Avenue – 105th Avenue – Brinckerhoff Avenue – Hollis Avenue | Lefferts Boulevard | Springfield Boulevard | 2 | 6.2 | 13.3 | $10,700,000 | elevated extension of the BMT Liberty Avenue Line (now part of the Fulton Street Line) includes branch connection to BMT Jamaica Line (BMT) at 168th Street, via 180th Street and Jamaica Avenue |

| Van Wyck Boulevard Line | 137th Street – Van Wyck Boulevard | 87th Avenue | Rockaway Boulevard | 2 | 2.3 | 4.6 | $6,600,000 | subway to about 116th Avenue, then elevated |

| 120th Avenue Line | 120th Avenue – Springfield Boulevard | Hawtree Street near North Conduit Boulevard | Foch Boulevard (now Linden Boulevard) |

4 to Van Wyck Boulevard 2 to Foch Boulevard |

5.23 | 13.92 | $9,500,000 | elevated |

| Bayside Line | Roosevelt Avenue – First Street – Station Road – 38th Avenue | Main Street | 221st Street | 3 to 147th Street 2 to 221st Street |

3.6 | 7.78 | $9,600,000 | extends the BMT/IRT Flushing Line as a subway to 155th Street, then elevated |

| College Point and Whitestone Line | 149th Street – 11th Avenue | Roosevelt Avenue and 147th Street | 11th Avenue and 122nd Street | 2 | 3.4 | 6.8 | $6,000,000 | subway to 35th Avenue, then elevated |

| Long Island City-Horace Harding Boulevard Line | Ditmars Avenue – Astoria Boulevard – 112th Street – Nassau Boulevard (Long Island Expressway) | Second Avenue | Cross Island Boulevard | 2 to Astoria Boulevard 4 to Parsons Boulevard 2 to Cross Island Boulevard |

8.1 | 26.71 | $17,700,000 | extends the BMT/IRT Astoria Line as an elevated, except that part of it may be depressed near Nassau Boulevard (Long Island Expressway) |

| Liberty Avenue Line | Grant Avenue | Lefferts Boulevard | 3 | 2.3 | 6.9 | $1,600,000 | owned by BMT, to be taken over ("recaptured") by IND now part of the Fulton Street Line | |

| Queens subtotal | 52.37 | 136.49 | $119,100,000 | |||||

| Total | 100.12 | 294.81 | $438,400,000 | |||||

Other plans during the same time

editRevised 1932 plan

edit| Borough | Number of route miles |

|---|---|

| Queens | |

| Brooklyn | |

| Manhattan | |

| The Bronx |

The IND expansion plan was revised in 1932. It differs from the 1929 plan, but there are 60.93 route‑miles (98.06 km), of which 12.49 miles (20.10 km) are in Manhattan, 12.09 miles (19.46 km) in the Bronx, 13.14 miles (21.15 km) in Brooklyn, and 23.21 miles (37.35 km) in Queens. It would include a new 34th Street crosstown line, a Second Avenue Subway line, a connection to the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway, and extensions of the IRT Nostrand Avenue Line, IRT Flushing Line, and BMT Astoria Line. It would have created a subway loop bounded by 2nd and 10th Avenues, and 34th and 125th Streets. This plan included no extensions to Whitestone, Queens, however, with the plan to instead serve more densely populated areas such as Astoria and the Roosevelt Avenue corridor.[28]

The plan would also take over the local tracks of the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway, and the Rockaway Beach Branch of the Long Island Rail Road.[28]

The table of route miles is as follows:[28]

| Line | Streets | From | To | Route miles | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manhattan | |||||

| Second Avenue Line | Water Street, Bowery, Chrystie Street, 2nd Avenue | Water Street | Alexander Avenue (Bronx) | 8.64 | |

| 34th Street Line | 34th Street | 2nd Avenue | 10th Avenue | 1.39 | |

| Worth Street, East Broadway and Grand Street Line | Worth Street, East Broadway, and Grand Street | Church Street | Lewis Street | 1.53 | |

| Houston Street Line | Houston Street | Essex Street | East River | 0.89 | |

| Manhattan subtotal | 12.49 | ||||

| The Bronx | |||||

| Alexander Avenue, Third Avenue, Boston Road, Melrose Road and East 172nd Street Line | Alexander Avenue, Third Avenue, Boston Road, Melrose Road and East 172nd Street | Harlem River | East 180th Street and Morris Park Avenue | 4.41 | |

| Morris Park Avenue Line | Morris Park Avenue and Wilson Avenue | Morris Park Avenue, East 180th Street | Boston Road | 3.35 | |

| 143d Street–Garrison Avenue and Lafayette Avenue Line | 143rd Street, Garrison Avenue, and Lafayette Avenue | Brook Avenue | Sound View Avenue | 2.48 | |

| Burke Avenue–Boston Road Line | Westchester Avenue, Brook Avenue | Burke Avenue | Baychester Avenue | 2.48 | |

| Bronx subtotal | 12.09 | ||||

| Brooklyn | |||||

| Stuyvesant Avenue–Utica Avenue Line | Stuyvesant Avenue, Utica Avenue | East River | Sheepshead Bay | 10.71 | |

| Fulton Street and Rockaway Boulevard Line | Fulton Street | Rockaway Avenue | Borough line with Queens | 2.43 | |

| Brooklyn subtotal | 13.14 | ||||

| Queens | |||||

| Rockaway Peninsula Line | Rockaway Beach Branch | Queens Boulevard | The Rockaways (Rockaway Park and Far Rockaway) | 14.92 | Was actually built south of Liberty Avenue |

| Van Wyck Boulevard Line | Van Wyck Boulevard | Hillside Avenue | Rockaway Boulevard | 2.30 | Eventually partially-built (~0.4 mi) and connects to the IND Archer Avenue Line |

| Hillside Avenue Line | Hillside Avenue | 178th Street | Springfield Boulevard | 2.48 | |

| Fulton Street and Rockaway Boulevard Line | Rockaway Boulevard, 120th Avenue | Borough line with Brooklyn | Springfield Boulevard | 3.51 | |

| Queens subtotal | 23.21 | ||||

| Total | 60.93 | ||||

Smaller plans

editOther plans, proposed during the same time as the IND Second System plans, included the following:

- (1931 plan) A line splitting from the Second Avenue Line north of Houston Street, running southeast under East 16th St, turning southwest under Avenue C, merging with the Houston Street Line, and crossing the East River from Stanton Street towards the huge line under South Fourth Street.

- (1931 plan) A line splitting from the Crosstown Line where it turns from Lafayette Avenue to Marcy Avenue, continuing under Lafayette Avenue and Stanhope Street to a junction with the line under Myrtle Avenue.

- (1932 plan) A rapid transit shuttle operating from a terminal adjacent to the IRT Flushing Line and Whitestone Landing operating over the Long Island Rail Road's Whitestone Branch. The line would have been under private operation and would have had a 5 cent fare.[29]

- (1939 plan) A line splitting from the South Brooklyn (Culver) Line at Fort Hamilton Parkway or Church Avenue, and running under Fort Hamilton Parkway to 86th Street. A branch would split to run under Ovington Avenue and Senator Street, with a tunnel under the Narrows to Staten Island at the St. George Terminal. The line would split, with the north branch ending at Westervelt Avenue around Hamilton Avenue, and the south branch ending at Grant Street around St. Pauls Street. It was presumably designed this way to provide future service to both the Main Line and North Shore Staten Island Railway lines.[30][31] The Staten Island Tunnel commenced construction in 1923 to serve the BMT Fourth Avenue Line, but was not completed.[32][33]

- (1940 plan, revised 1945) The IND Fulton Street Line would connect to what is now the IND Rockaway Line. A branch of the IND Fulton Street Line would run to a stub-end terminal at 105th Street. The line, east of Euclid Avenue, would be 4 tracks until Cross Bay Boulevard, where the two branches would split.[34]

- (unknown date) A third 2-track tunnel under the East River, from the north side of the South Fourth Street/Union Avenue station (as built for six tracks) west to Delancey Street.

- (unknown date) A line splitting from the Stuyvesant Avenue line, going southeast under Broadway.

- (unknown date) A line under Flushing Avenue from the huge line under Beaver Street to Horace Harding Boulevard (Long Island Expressway).

- (unknown date) A 4 track subway under Bedford Ave in Brooklyn connecting to the Worth St Subway and 2nd Ave Subway.

An earlier plan in 1920 had an even more expansive plan, with several dozen subway lines going across all five boroughs.[35]

Provisions for new lines

editThe following provisions were made for connections and transfers to the new lines. It is of note that only four of these provisions were completed.

- At Second Avenue on the IND Sixth Avenue Line, the ceiling drops at the west end. Above the ceiling is a provision for a four-track IND Second Avenue Line. The future Second Avenue Line will not utilize this provision; it will instead be built under the station, if a transfer station is ever built.

- At East Broadway on the IND Sixth Avenue Line (under Rutgers Street at this station), part of a two-track station was built for the IND Worth Street Line under East Broadway, above the existing line. Most of the constructed portion is now part of the mezzanine, with a small unused section blocked by a door.

- At Broadway on the IND Crosstown Line, traces of passageways are visible going towards a six-track station on the line to Utica Avenue, as well as a stair to an upper mezzanine on top of the unfinished station.

- At Utica Avenue on the IND Fulton Street Line, a four-track station above can be seen in the ceiling of the existing station. This portion of the Utica Avenue Line was built with the construction of the Fulton Street Line. Ramps were built from the mezzanine to the platforms because the normal vertical distance of ten feet from the mezzanine floor to the platforms was increased to 25 feet in anticipation of the Utica Avenue Line. The existing mezzanine passes over the unused space.[36][37]

- At Roosevelt Avenue on the IND Queens Boulevard Line, a two-track upper level was built for the Winfield Spur towards the line to the Rockaways. Unlike the other stations, this one was completed, except for track.

- Hillside Avenue considerably widens between 218th Street and 229th Street in Queens Village, and gains a very wide median. This section was widened in the 1930s to accommodate construction of the proposed eastern terminus of the IND Queens Boulevard Line at Springfield Boulevard and Rocky Hill Road (Braddock Avenue) and to accommodate an underpass for Hillside Avenue underneath Springfield Boulevard and Braddock Avenue.[38][39][40] Six station entrances would have been provided at Springfield Boulevard and Braddock Avenue. The station would have stretched as far east as 88th Avenue. The two tracks would have continued to 229th Street.[41]

- The center tracks on the IND Sixth Avenue Line dead end at the curve from Houston Street to Essex Street; these were planned to continue through a new East River tunnel to Williamsburg and south to the proposed Utica Avenue line towards Sheepshead Bay.

- The tracks that the IND 63rd Street Line uses to split from the IND Sixth Avenue Line were built for a similar proposed line under 61st Street, connecting to the Second Avenue Subway.

- The Lexington Avenue–63rd Street subway station has two island platforms, which were originally built with now-demolished walls on their northern sides. The platforms were designed to provide a cross-platform interchange to the Second Avenue Subway.

- The upper level relay tracks east of 179th Street on the IND Queens Boulevard Line were intended to continue toward Floral Park, and the tunnel is designed to allow for such a future extension.[42]: 123

- The relay tracks east of Euclid Avenue on the IND Fulton Street Line were intended to continue toward Cambria Heights in Queens.

- The Nevins Street station on the IRT Eastern Parkway Line has an unused center trackway and an unused lower level intended for expansion into northern or southern Brooklyn.

- South of the 36th Street station on the BMT Fourth Avenue Line, there are three trackways that diverge from the line at a flying junction. These trackways end under the eastern curb of Fourth Avenue.

- The BMT Fourth Avenue Line has provisions for two more tracks south of 59th Street, where the line becomes double-tracked:

- There are four trackways on the BMT Fourth Avenue Line bridge over the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch despite the fact that only the northernmost two tracks are in use.

- The 86th Street station on the BMT Fourth Avenue Line appears to have "escapes" in the wall bricked over along the Manhattan-bound track, for the never-built fourth tracks.[9]

- The northbound side platforms of Bay Ridge Avenue and 77th Street do not have platform pillars because the platforms were supposed to be temporary; the southbound platforms do have pillars, however.

- Bellmouths for uncompleted lines are scattered in numerous stations, including 21st Street–Queensbridge, 59th Street, 63rd Drive–Rego Park, Bowery, Canal Street, and Woodhaven Boulevard:

- East of 21st Street–Queensbridge, before the IND 63rd Street Line connects to the IND Queens Boulevard Line, the tracks veer left while the tunnel wall goes straight. The bellmouths were part of a proposed super-express bypass running under the LIRR mainline between Queens Boulevard and Forest Hills. This plan was not in the original Second System plan, but rather, as part of the Program for Action plan that had the tracks from 21st Street–Queensbridge go straight to Forest Hills.[43]

- There are bellmouths and space for two additional trackways (for a total of six) on the BMT Fourth Avenue Line south of 59th Street. These provisions were for the Staten Island Tunnel, which would have intersected with the line south of 59th Street.[9]

- East of 63rd Drive–Rego Park on the IND Queens Boulevard Line, bellmouths were built for a proposed connection to the LIRR's Rockaway Beach Branch. They may be used if the Rockaway Beach Branch were ever reused for subway service.

- A line to the Rockaways would have split from the IND Eighth Avenue Line (under Church Street at this point), east under Worth Street. The junction was built and is used by the local tracks to World Trade Center. The branch to the Rockaways was completed and connected to the IND Fulton Street Line in 1956.

- Two bellmouths have since been completed, but were previously unused.

- The completed IND 63rd Street Line, which the F and <F> train uses to cross the East River, was designed and built with bellmouths to allow for the construction of connections to the planned Second Avenue Subway for service to/from the north and south along Second Avenue. These bellmouths were completed and opened in 2017.

- A junction was built on the IND Queens Boulevard Line for the line under Van Wyck Boulevard. The junction was completed and has been connected to the IND Archer Avenue Line.

Shells built

editThe South Fourth Street shell, if complete, was supposed to handle service as follows:

| Level 1 | Northbound | ← Broadway line westbound |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound | ← Broadway line eastbound → | |

| Level 2 | Northbound | ← Utica Avenue express to Sixth Avenue |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound | ← Flushing/Utica Avenues local (termination platform) | |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound | ← Flushing Avenue express to Eighth Avenue | |

| Southbound | ← Flushing Avenue express from Eighth Avenue → | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound | ← Flushing/Utica Avenues local → | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound | ← Utica Avenue express from Sixth Avenue → | |

| Level 3 | Southbound | ← Utica Avenue local → |

| Island platform | ||

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound | ← Utica Avenue local → | |

Note: The locals would have short-turned here. There would have been two tunnels under the East River: East Houston Street and Grand Street.

Another plan for the South Fourth Street shell was simpler (and was the plan that was partially completed):

| Level 1 | Northbound | ← Flushing Avenue express to Eighth Avenue |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound | ← Utica Avenue express to Sixth Avenue via East Houston Street | |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound | ← Utica Avenue local to Sixth Avenue via Stanton Street | |

| Southbound | ← Utica Avenue local from Sixth Avenue via Stanton Street → | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound | ← Utica Avenue express from Sixth Avenue via East Houston Street → | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound | ← Flushing Avenue express from Eighth Avenue → | |

Note: The Flushing Avenue local would have diverged off to the IND Crosstown Line. There would have been three tunnels under the East River: East Houston Street, Stanton Street, and Grand Street.

The Utica Avenue station shell, if complete, would be in the standard local-express-express-local platform configuration.

The Jackson Heights–Roosevelt Avenue shell, a two-trackbed island-platformed station, would have been for local trains terminating at the station. Express trains would have stopped at the lower level (IND Queens Boulevard Line) platforms.

1940–1999 plans

editAfter World War II and up until the late 1990s, the New York City Subway did not expand much. Only 28 stations opened in that time, compared to the remaining 393 stations, which opened from the 1880s to before World War II. As such, there have been many plans to expand the system during this time period.

1938–1940

editThe New York City Board of Transportation revised its plans for subway expansion, and released them in 1938 and 1940.

- The remnant of the IRT Ninth Avenue Line at 155th Street would connect with the IRT Lenox Avenue Line, giving riders of the Jerome Avenue Line service to Manhattan's West Side.[42]: 123 This project was never undertaken because of the high cost of modifying the third rail in the Sedgwick Avenue and Anderson–Jerome Avenues tunnel section to accommodate new subway cars.[9]

- The New York, Westchester and Boston Railway's abandoned right-of-way would have been rehabilitated and connected to the IRT Pelham Line.[9]

- The IND Concourse Line would have been extended eastward to Gun Hill Road from 205th Street.[9]

- The Second Avenue Subway would originate at Harding Avenue in the Bronx, and connect into the Court Street station in Brooklyn as a two-track and four-track line.[9] A yard would have been constructed to store the line's equipment.[46]: 703 The first phase would end the line at East 139th Street. The Main Line and its connections to other subway lines was to have cost $213.95 million, while the future Bronx extension would have cost $130.16 million.[47]: 212

- An extension of the IRT Lenox Avenue Line would have been built so it could connect with the IRT Ninth Avenue Line.[48]

- Two express tracks would be built on the IND Sixth Avenue Line between West 9th Street and West 31st Street for $19.27 million. This was viewed as a requirement for a Second Avenue Line.[49]: 371

- The Seventh Avenue Line Extension would extend the Broadway Line north from 59th Street via a tunnel under Central Park to 72nd Street, before turning east into Queens via Northern Boulevard to Jackson Heights. It was to have been built as a two-track and four-track line, and it would have cost $89 million. The second phase would extend the line as a two-track line along Corona Avenue and Horace Harding Boulevard from Jackson Heights to Marathon Parkway. A storage yard would be built. This phase would have cost $51.82 million. A connection between the new line and the Crosstown Line was to have been built at 23rd Street (Ely Avenue) for $10.95 million.[48][49]: 371

- A connection between the Seventh Avenue Extension and the Rockaway Line would be built at 99th Street, costing $9.2 million.[49]: 371 The Rockaway Beach Branch of the LIRR would be purchased and converted for subway operation. Service to the Rockaway would be provided through a connection to the IND Queens Boulevard Line. The extension would have cost $42.38 million. In addition, $2.55 million would be spent on a two-track subway an open-cut connection between the Rockaway Line and the Fulton Street Line.[47]: 213 Only the portion south of Liberty Avenue was completed.[9]

- An extension of the BMT Broadway Line, from 57th Street–Seventh Avenue to 145th Street, would run via Central Park and Morningside Drive.[9]

- A crosstown line via Worth Street would serve as a branch of the IND Eighth Avenue Line's local tracks. The line would have branched off at Church Street, from where it would run via Worth Street and East Broadway to Lewis Street. This two-tracks segment would have cost $15.2 million.[49]: 371 The line would then tunnel under the East River between Lewis Street to Driggs Avenue. This section would have cost $18.5 million.[49]: 372 The South Fourth Street junction would be completed.[9]

- The IND Queens Boulevard Line and BMT Broadway Line would be connected through the construction of a connection at 11th Street. The connection would be between the Queens Boulevard Line's local tracks at Queens Plaza and the BMT 60th Street Tunnel.[9]

- The IND Queens Boulevard Line would be extended from 178th to 184th Streets.[48]

- The IRT Flushing Line would be extended from Main Street to Bell Boulevard, as a two-track and a four-track line, along Roosevelt Avenue. The line would be constructed in a tunnel, embankment, and an open cut, costing $12.07 million. An additional extension would be constructed to College Point, running along 149th Street and 11th Avenue as an elevated line from Roosevelt Avenue to 122nd Street, costing $14.1 million.[9][49]: 371

- Subway service would be extended eastward along Hillside Avenue to Little Neck Parkway. The line would be an extension of the IND Queens Boulevard Line as a four-track line to 212th Street, and then as a 2-track line to its terminus at Little Neck Parkway.[9][49]: 371 The segment to 184th Street was to have cost $3.455 million, while the segment to 212th Street was to have cost $16.355 million.[50]

- The provision at Van Wyck Boulevard for a future line would be completed, and a new two-track line would be built to Rockaway Boulevard.[9]

- The IND Fulton Street Line would get an eastward extension; it would first be extended to 106th Street as a four-track line,[48][49]: 371 where it would connect to the IND Rockaway Line. Afterwards, the line would stretch along Linden Boulevard to 229th Street in Eastern Queens. The line was to go to a two-track terminal at 105th or 106th Streets, with intermediate stops at 75th or 76th Streets and at 84th or 85th Streets (both proposed local stops), as well as at Cross Bay Boulevard (a proposed express stop).[10]: 137, 142 [51] In 1951, these relay tracks east of Euclid Avenue were still planned to go as far as 105th Street, with a connection to the IND Rockaway Line east of Cross Bay Boulevard.[34] In May 2004, this idea resurfaced, with an attached track map drawn up.[52] If the line were ever built, Pitkin Avenue would have been routed to the east rather than to the southeast at 80th Street, and Linden Boulevard between Conduit and Rockaway Boulevards would have been built to facilitate the line.

- A new IND line would run from the Lower East Side to Avenue U in Brooklyn, with a possible extension to Floyd Bennett Field.[48] The new line would run via Houston Street and Essex Street in Manhattan, and via Utica Avenue and Flatbush Avenue.[9]

- Service on the IRT Nostrand Avenue Line would be extended down Nostrand Avenue to Voorhies Avenue in Sheepshead Bay as a two-track line. The extension would be constructed as a subway until Avenue T, where it would emerge as an elevated line to Voorhies Avenue.[9] It would have cost $22.7 million.[49]: 372

- The IND would be extended to South Brooklyn with a connection at Cortelyou Road between its South Brooklyn Line and the BMT's Culver Line. This was the only completed Brooklyn proposal.[9]

- Dyker Heights would get service with the construction of a branch of the BMT Culver Line via 37th Street, Fort Hamilton Parkway and 10th Avenue to 86th Street. In the vicinity of Fort Hamilton Parkway, a connection would be constructed between the BMT West End Line and the IND South Brooklyn Line.[9] Extension work was approved sometime before 1940, and plans were drawn up.[53]

- A connection between the BMT Franklin Avenue Line and the IND Crosstown Line would be built through the construction of a line under Lafayette Avenue.[9]

- Subway service would be provided to Staten Island for the first time, with the construction of a tunnel under the Narrows connecting at 68th Street to the BMT Fourth Avenue Line and with the Staten Island Railway at New Brighton and Tompkinsville.[9]

The IND Concourse Line got funding to be extended eastward past 205th Street, but Bronx residents wanted to rehabilitate the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway right-of way. This funding was reallocated, and the old NYW&B line became the IRT Dyre Avenue Line in December 1941, and the IND Concourse Line extension was not brought up again until 1968.[9]

1940s: Smaller plans

editIn 1942, Mayor Benjamin F. Barnes of Yonkers proposed that the Getty Square Branch of the New York Central's Putnam Division be acquired for an extension of the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line from Van Cortlandt Park. This service would replace the service operated by the New York Central, which was slated to be discontinued by the New York Central.[54]

A rail link to LaGuardia Airport was proposed in 1943, when the city Board of Transportation proposed an extension of the BMT Astoria Line (currently served by the N and W trains) from its terminus at Ditmars Boulevard.[55][56] The line would have run along Ditmars Boulevard, and would have cost $10.5 million.[49]: 371

In 1946, the Board of Transportation issued a $1 billion plan that would extend the subway to the farthest reaches of the outer boroughs.[57][58]

- A branch of the BMT Fourth Avenue Line at 59th Street under the Narrows to Saint Nicholas Street and Grent Street in Staten Island.

- A branch of the IND Fulton Street Line running via Utica Avenue to Avenue U.

- An extension of the IRT Nostrand Avenue Line from Flatbush Avenue to Voohries Avenue.

- A line branching off of the IND Crosstown Line running via Franklin Avenue connecting with the BMT Brighton Line. This would have replaced the BMT Franklin Avenue Line.

- The extension of the IND Fulton Street Line to Euclid Avenue would continue to be built, and would be extended to 229th Street and Linden Boulevard.

- The completion of the Culver Ramp, connecting the IND Culver Line with the BMT Culver Line.

- A branch of the IND Culver Line running via Tenth Avenue and Fort Hamilton Parkway to 86th Street, with a connection to the BMT West End Line. West End service would run via the Culver Line and would alleviate congestion at DeKalb Avenue Junction. In order to provide access to the BMT Fourth Avenue Line, the Culver Shuttle would be extended to 36th Street.

Even though the Board of Transportation did not approve these ideas, they were still proposed.

- A line branching off of the IND Eighth Avenue Line running via Worth Street and East Broadway and running under the East River to Driggs Avenue.

- A new trunk line built along Second Avenue with a connection at Court Street to the IND Fulton Street Line.

- Lines in Queens to the Rockaways, LaGuardia Airport, Idlewild Airport (now called JFK Airport), College Point, Bayside, Little Neck, Douglaston, Saint Albans and Bellerose.

In 1949, the Board of Transportation issued a $504 million plan to increase capacity on several subway lines through the construction of a new trunk line under Second Avenue.[59]

- The rebuilding of DeKalb Avenue that would remove the bottleneck and increase capacity by 18 tph.[59]

- IND Sixth Avenue Line express tracks between West Fourth Street and 34th Street.[59]

- A new subway line under 57th Street connecting the IND Sixth Avenue Line and the proposed Second Avenue trunk line.[59]

- A four-track Second Avenue Subway would originate from a connection to the IRT Pelham Line at 138th Street, the Bronx, to Grand Street, Manhattan. The connection to the Pelham Line would allow for eight additional trains per hour operating between Manhattan and the Pelham Line. It would then be possible to operate 10-car trains via the line and it would also be possible to operate full express service via the line's center express track. The trains operating via Nassau Street would go to Brooklyn via the Montague Tunnel. During non-rush hours trains would terminate at Broad Street. There would be a passageway built from Grand Central via 43rd Street to Second Avenue to permit transfers.[59]

- The IRT Pelham Line would be rebuilt to accommodate the wider BMT-IND cars to operate via the Second Avenue Line. The connection would provide the Pelham Line with direct service to Sixth Avenue, Second Avenue and Brooklyn.[60]: 1200 The station platforms, and third rail would have had to be adjusted as they were put in place for the narrower IRT trains. The line was built with this conversion in mind, however. Westchester Yard would have been expanded to accommodate the additional trains added to the line. Since trains to the Pelham Line would no longer use the Lexington Avenue Line, there would be additional capacity for trains to run via the IRT White Plains Road Line and the IRT Jerome Avenue Line. Improved service on the Pelham Line was projected to stimulate growth in the areas of the East Bronx served by the line. The East Bronx was seen to have great potential for industrial growth and other areas suitable for development as residential and recreational areas.[59]

- An improved connection between the IRT Lexington Avenue Line and the IRT White Plains Road Line would be built using the tunnel under the Harlem River used by the IRT Pelham Line, and would allow for the full use of the capacity on the White Plains Road Line and the Jerome Avenue Line. Eight additional trains per hour would be added to the White Plains Road Line and fourteen additional trains per hour would be added to the Jerome Avenue Line. The additional service on the Jerome Avenue Line would make use of the third track for express service.[59]

- The Second Avenue Line trunk would be extended to 149th Street to allow for a transfer to the Third Avenue Elevated. This would permit the demolition of the Third Avenue Elevated south of 149th Street, which was seen as uneconomical to operate, ugly and a hindrance of the avenue below it.[59]

- Connection of the IRT Dyre Avenue Line to the IRT White Plains Road Line. The direct service was predicted to stimulate growth along its route.[59]

- Connections would be made to the BMT Nassau Street Line, the Williamsburg Bridge, and the Manhattan Bridge. The Sixth Avenue Line would also be connected to the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges. The connection between the Nassau Street Line and the Manhattan Bridge south tracks would be eliminated. This would allow for thirty additional trains to operate between Midtown Manhattan and Brooklyn.[59]

- The lengthening of platforms on the BMT lines in Brooklyn would increase capacity and would allow 10-car trains from Second Avenue to run over any section of the BMT and IND.[59]

- Increase in capacity on the BMT Brighton Line, BMT Sea Beach Line, BMT West End Line, and the BMT Fourth Avenue Line by 8 tph in total by adding a connection from the BMT Culver Line to the IND Culver Line at Ditmas Avenue. The additional capacity would result from the fact that trains operating via the former BMT Culver Line would not run through DeKalb Avenue Junction.[59]

- A connection between the IND Queens Boulevard Line at Queens Plaza to the BMT 60th Street Tunnel that would increase capacity between Queens and Manhattan by 20 tph. This connection would permit the full use of the capacity of the Queens Boulevard local tracks.[59]

- The construction of a ramp connecting the IND Fulton Street Line with the Fulton Street Elevated on Liberty Avenue. Six stations on the elevated would have their platforms extended to accommodate 10-car trains. This would make possible the demolition of the BMT Fulton Street Line between Grant Avenue and Rockaway Avenue and the demolition of the BMT Lexington Avenue Line.[59]

1950–1951

editOn June 21, 1950, a plan was created by the Board of Transportation and sent to Mayor O'Dwyer concerning rapid transit expansions in Queens. The total cost of the plan would have been $134.5 million. Many things were planned:[61]

- The rebuilding of DeKalb Avenue that would increase capacity by 18 tph.

- IND Sixth Avenue Line express tracks

- A four-track Second Avenue Subway between 149th Street, the Bronx, to Grand Street, Manhattan.

- Connections would be made to the BMT Nassau Street Line, the Williamsburg Bridge, and the Manhattan Bridge. The Sixth Avenue Line would also be connected to the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges.

- The Rockaway Beach Branch of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) would be acquired by the City and an embankment would be created with two bridges for the right-of-way over Jamaica Bay. To provide a connection to the rest of the subway system, a track connection would be built to the IND Fulton Street Line.

- The Rockaway Beach Branch would run alongside the LIRR main line tracks as a super-express bypass. Once in Woodside, the line would go underground running under Sunnyside Yards and Long Island City to the East River. It would then go under the East River and 76th Street in Manhattan to the Second Avenue Line.

- The bypass would also have a connection to the LIRR's Port Washington Branch with subway service running to Bayside.

- Connections to the IRT Pelham Line at Third Avenue–138th Street and to the IRT White Plains Road Line at Third Avenue–149th Street.

On September 13, 1951, the Board of Estimate approved a plan put forth by the New York Board of Transportation that would cost $500 million.[62][63] Many things were planned:

- A six-track Second Avenue Subway between 149th Street, the Bronx, to Grand Street, Manhattan. This line would handle 68 trains per hour (tph) (34 tph on the express tracks and 34 tph on the local tracks).[62]

- The line would have a track connection to the IRT Pelham Line at Third Avenue–138th Street and there would be a branch terminating at Third Avenue–149th Street to permit a transfer to the Third Avenue Elevated in the Bronx. This would allow for the elimination of the Third Avenue Elevated south of 149th Street.

- A tunnel to the IND Sixth Avenue Line via 57th Street.

- A super-express bypass line to the LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch with a new tunnel under the East River.

- A connection from the IND Queens Boulevard Line to the Rockaway Beach Branch and IND Rockaway Line.

- Various Bronx IRT projects:[62]

- Increase in capacity on the IRT Pelham Line.

- Connection of the IRT Dyre Avenue Line to the IRT White Plains Road Line.

- Increase in capacity on the IRT White Plains Road Line north of Gun Hill Road by 8 trains per hour. (At the time, the IRT Third Avenue Line still connected to the IRT White Plains Road Line at Gun Hill Road.)

- Increase in capacity on the IRT Jerome Avenue Line by 9 trains per hour.

- The Chrystie Street Connection:[62]

- IND Sixth Avenue Line express tracks.

- DeKalb Avenue rebuilding, including closure of the Myrtle Avenue station. This would increase capacity by 18 tph.

- Increase in capacity on the BMT Fourth Avenue Line's local tracks by 4 tph.

- Increase in capacity on the BMT Sea Beach Line by 9 tph.

- Increase in capacity on the BMT West End Line by 5 tph.

- Connection of the IND Second Avenue and IND Sixth Avenue Lines to the BMT Jamaica Line and to the Manhattan Bridge.

- Increase in capacity on the BMT Brighton Line by 8 tph by adding a connection from the BMT Culver Line to the IND Culver Line at Ditmas Avenue.[62]

- 60th Street Tunnel Connection.[62]

- Extension of the IRT Nostrand Avenue Line to Voorhies Avenue.[62]

- Construction of the IRT Utica Avenue Line from Crown Heights–Utica Avenue to Kings Plaza.[62]

The Board of Estimate requested that the Board of Transportation evaluate a spur of the IRT Pelham Line to Throggs Neck in the Bronx.

1954

editThe Board of Estimate accepted the following items into its 1954 budget from the New York City Transit Authority:

- The elimination of the DeKalb Avenue bottleneck on the BMT.[64]

- The construction of the Nostrand Avenue extension to Avenue U. It would have cost $51.7 million.[64]

- The extension of the IND Fulton Street Line to the BMT Liberty Avenue Elevated.[64]

- A start on the Second Avenue Subway in Chrystie Street.[64]

- Adding express tracks to the IND Sixth Avenue Line.[64]

In March 1954, the Transit Authority issued a $658 million construction program including the following projects:[65]

- A Second Avenue trunk line, which would have allowed 34 more trains to midtown per hour.[65]

- A tunnel at 76th Street that would connect to the Second Avenue Line that would run under the East River and connect with the existing Long Island Rail Road main line.[65]

- An increase of service on the IRT White Plains Road Line by eight trains per hour due to the construction of the Second Avenue Line.[65]

- The connection of the IRT White Plains Road Line and the IRT Dyre Avenue Line was nearing completion and would provide direct service to Manhattan and Brooklyn.[65]

- Fourteen additional trains per hour would be able to operate on the IRT Jerome Avenue Line if the IRT Pelham Line was connected to the Second Avenue Subway. Service would have been tripled on the Pelham Line.[65]

- The completion of the 60th Street Tunnel Connection, which was under construction, would increase service to Jamaica by fifteen trains per hour.[65]

- The addition of two tracks to the IND Sixth Avenue Line would allow express service.[65]

- The elimination of the DeKalb Avenue bottleneck on the BMT, which would allow eighteen more trains to be operated per hour.[65]

- The construction of the Nostrand Avenue extension to Avenue U.[65]

- The construction of the Chrystie Street Connection.[65]

- The connection of the IND South Brooklyn Line and the BMT Culver Line at Ditmas Avenue would be opened in the spring, and would have allowed eight more trains to run per hour on the BMT Brighton Line.[65]

- Bottlenecks would be removed at Grand Central on the IRT East Side Line and at 96th Street on the IRT West Side Line.[65]

In 1954, Regional Plan Association advocated for an extension of the BMT Canarsie Line from Eighth Avenue to Jersey City under the Hudson River. The tunnel under the Hudson would have cost $40 million. The extension would have provided access to commuter railroads in New Jersey as most lines converged there, and the lines that didn't would be rerouted to stop there. The RPA also suggested having a parking lot there for access from the Pulaski Skyway and the New Jersey Turnpike. It was suggested that either the New York City Transit Authority, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey or the Bi-State Metropolitan Rapid Transit Commission would do the construction.[14]

1961

editJohn T. Clancy, a Democratic incumbent running for Queens Borough President in 1961 proposed third tracking the BMT Jamaica Elevated Line to provide express service, and reactivating the Rockaway Beach Branch from Rego Park to Liberty Avenue.[66]

1962–1963

editIn July 1962, the NYCTA announced that it had asked the city for money to build a $190 million high-speed, non-stop subway line from Midtown to the Bronx. The line would have only operated during rush hours. It was estimated that if the funds were given to the project, it would be completed in 1970. The line would be a two-track line running from 59th Street between Fifth and Seventh Avenues to the Bronx, running under Central Park. Running non-stop for 6.5 miles, it would have been the longest continuous run in the subway system. The line, on its southern end, would connect to the BMT Broadway Line at Seventh Avenue near 59th Street and to the IND Sixth Avenue Line near 58th Street and Sixth Avenue.[67]

The line would then run through a deep tunnel under Central Park until 110th Street. There would be provisions for a future crosstown line under 76th Street to Queens. The line would then turn east and run along Madison Avenue to 138th Street. One branch would connect to the express track of the IRT Pelham Line, which would be converted to accommodate larger B Division trains. In the morning rush hour, trains from Pelham Park would only make express stops. A new stop would be built at 138th Street and Grand Concourse where transfers would have been available to the IRT White Plains Road and IRT Jerome Avenue Line trains.[68]

The second branch would continue under the Grand Concourse until 161st Street where it would connect to the IND Concourse Line at 161st Street. This connection would allow for the diversion of Concourse Line express trains onto the new line, allowing for the addition of an equal number of trains to the IND Central Park West express service and provide relief to that line. The construction of this line was viewed as necessary to relieve the IRT Lexington Avenue Line.[69]

In February 1963, the New York City Transit Authority issued a preliminary proposal for rapid transit expansion in the borough of Queens. The plan was designed to relieve congestion on the IRT Flushing Line and IND Queens Boulevard, to deal with expected population growth, and to provide service to areas of the borough without transit service. To expand service to other areas of the borough a new trunk line would be built to provide the necessary capacity. The planned extensions were expected to relieve crowding on the IRT Flushing Line by 22 percent and on the IND Queens Boulevard Line by 19 percent.[70]

The first phase of the transit expansion would build a trunk line connecting the IND Queens Boulevard Line's local tracks at Steinway Street and Broadway using existing provisions with the IND Sixth Avenue Line and BMT Broadway Line in Manhattan. The new line would have run under 34th Avenue, a new tunnel under the East River, and 76th Street before turning south under Central Park. Connections would be made to the IND Sixth Avenue Line at 58th Street and to the BMT Broadway Line's stub tracks at 59th Street and Seventh Avenue. In Manhattan, there would have been a transfer connection to the 77th Street station on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line and a station in Central Park at 70th Street.[70]

Provisions would be built for a planned extension to the Bronx. At Steinway Street, switches would be constructed to all GG trains from Brooklyn to terminate there. The new 4.5 miles (7.2 km) line would have provided an additional 30 trains per hour between Queens and Manhattan with a future northern extension. Initially, the line would be used for 15 trains per hour running to the IND Sixth Avenue Line from the IND Queens Boulevard Line. The construction of the trunk line was expected to cost $138.6 million, of which $37.4 million would be spent for the section south of 76th Street. The earliest possible date for the completion of the line would have been 1970.[70]

To provide service to unserved areas of Queens, three additional routes were considered. The first route would have served northern and northeastern Queens, running along 34th Avenue, Northern Bouelvard, Main Street, Kissena Boulevard, Parsons Boulevard, and one of the Horace Harding Expressway service roads to Springfield Boulevard. The 10.3 miles (16.6 km)-line would have consisted of two tracks and would have cost $219.4 million. The second route would be a branch of the IND Fulton Street Line heading under Linden Boulevard and Merrick Boulevard to Springield Boulevard.[70]

Two options were considered for this line. The first option would have branched off of the Fulton Street Line near Pitkin Avenue and Euclid Avenue using existing provisions in the tunnel. The second option would have extended the Liberty Avenue Elevated from Lefferts Boulevard. This option would have required the acquisition of private property to widen Liberty Avenue so that the line could transition from an elevated line to a subway line and to make the turn from Liberty Avenue and Linden Boulevard. The subway option would have been 6.6 miles (10.6 km) long and would have cost $116 million while the elevated/subway option would have been 4.5 miles (7.2 km) and would have cost $80.8 million.[70]

The third route would have connected the IND Rockaway Line to the IND Queens Boulevard Line using the Rockaway Beach Branch and an existing provision in the tunnel east of 63rd Drive. The Rockaway Beach Line had been abandoned by the Long Island Rail Road on June 8, 1962. A new stop would be built at Linden Boulevard to connect with a new subway line. This line was expected to cost $39.9 million.[70]

In addition to expanding service to Queens, service to the Bronx would have been expanded as well. The new trunk line connecting the BMT Broadway Line and IND Sixth Avenue Line to Queens south of 76th Street would have been used for the new line to the Bronx. This line would have run under the center of Central Park and then running via Fifth Avenue once out of the park at 110th Street, and would continue under the East River with a branch connecting to the IRT Pelham Line, which would have been modified in order to fit B Division subway cars, and a branch continuing up the Grand Concourse and then connecting to the IND Concourse Line.[71][72]

In May 1963, the New York City Planning Commission proposed the following in response to the NYCTA's proposal:[71]

- An implementation of skip-stop service on the BMT Jamaica Line.[71]

- An extension of a proposed Madison Avenue Line and the IND Sixth Avenue Line operating via 59th Street, with two branches.[71][72] One branch would have operated along Second Avenue with a branch connecting to the IRT Pelham Line, which would have had to be modified to fit B Division subway cars, and a branch connecting to the IND Concourse Line.[71][72] The other branch would have continued under the East River, and would have been connected to the Long Island Rail Road main line in the Sunnyside area.[71][72] Subway trains would have continued via the Port Washington Branch to Little Neck, and via the LIRR Main Line to Rego Park, where it would have turned via the former Rockaway Beach Branch and then would have turned onto the Lower Montauk Branch, and would have continued on the branch through Jamaica, where it would continue via the Atlantic Branch until Rosedale, staying within city limits.[71][72] The report claims that its proposed routes would serve up to twice as many people as the NYCTA's proposed routes.[71][72]

| Rail Transit Services | Present Population Served | 1985 Projected Population Served | ||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Existing Line | 900,000 | 50 | 985,000 | 49 |

| Long Island Lines | 305,000 | 17 | 360,000 | 18 |

| Transit Authority Proposal | 140,000 | 8 | 185,000 | 9 |

| Total Queens Population | 1,810,000* | 100 | 2,000,000 | 100 |

| * Based on 1960 Census | ||||

- A two-track Madison Avenue Line would have run from the proposed 59th Street tunnel via Madison Avenue and would have tied into the then-underutilized BMT Broadway Line in the vicinity of Madison Square.[71][72]

- In the vicinity of City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan, a connection between the BMT Nassau Street and Broadway Lines would have carried the Madison Avenue service through the financial district at Wall Street and Broad Street.[71][72] Another connection in Lower Manhattan would have been built connecting the IND Eighth Avenue Line and the BMT Broadway Line in the area of the former Hudson Terminal (today's World Trade Center).[71][72]

| CPC Proposal | TA Proposal | |||

| Route Miles | Cost $ Million |

Route Miles | Cost $ Million | |

| Queens Tunnel and Connections | 2.3 | $75 | 4.5 | $139 |

| Madison Avenue Line | 1.9 | 86 | – | – |

| Downtown Improvements | 2.7 | 23 | – | – |

| Queens Extension | 25.0 | 114 | 20.7 | 375 |

| Bronx Tunnel | 6.6 | 179 | 6.0 | 163 |

| Total | 38.5 | $477 | 31.2 | $677 |

1968

editProposed lines

editSimilar plans were made by the New York City Transit Authority in 1968.[73][74] They included:

- The IND Second Avenue Line with connections to IRT Dyre Avenue Line at East 180th Street, and the IRT Pelham Line at Whitlock Avenue[75]

- A crosstown line under 34th Street from 12th Avenue to 1st Avenue[75]

- IND/BMT 63rd Street Line

- A new line running along Park Avenue in the Bronx to replace the Third Avenue Elevated[75]

- Super-express bypass of IND Queens Boulevard Line[75]

- New line splitting from the IND Queens Boulevard Line under the Long Island Expressway to Kissena Boulevard in Phase I and to Springfield Boulevard in Phase II[76]

- Archer Avenue Line to Springfield Boulevard branching off of the BMT Jamaica Line at 127th Street and off of the Queens Boulevard Line at bellmouths railroad north of the Van Wyck Boulevard station.[75]

- IRT Nostrand Avenue Line extension to Avenue W in Sheepshead Bay.[75] This was by then the fifth time that the Nostrand Avenue extension was proposed.

- A new line branching off of the IRT Eastern Parkway Line and running under Utica Avenue to Avenue U[75]

- Extension of the BMT Canarsie Line to Nostrand Avenue or JFK Airport

- Extension of the IRT New Lots Line to Linwood Street and Flatlands Avenue

- Extension of the IND Concourse Line to White Plains Road

Completed lines

editThe Archer Avenue Lines are two lines, split between the BMT and IND, mostly running under Archer Avenue in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens. Conceived as part of these 1968 expansion plans, they opened on December 11, 1988.[77] There are stub-end tunnels east of the line's northern terminus, Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer, on both levels, which extend past the station for possible future extensions.[78]

The 63rd Street Lines are two lines also split between the BMT and IND. The short BMT line connects the express tracks of the BMT Broadway Line from 57th Street–Seventh Avenue to Lexington Avenue–63rd Street, where it now runs through to the Second Avenue subway. The IND line runs from the IND Sixth Avenue Line at 57th Street in Manhattan east under 63rd Street and the East River through the 63rd Street Tunnel to the IND Queens Boulevard Line in Queens.[79] There is a stub-end tunnel at the northern terminus of the IND line that is intended for the Queens super-express bypass.[80]

1970s

editIn Lower Manhattan, plans were made for the following:[81]: 7

- A new terminal for IRT Seventh Avenue locals to South Ferry

- A track connection between the Hudson Terminal (now World Trade Center) on the IND Eighth Avenue Line and Cortlandt Street on the BMT Broadway Line, both in Manhattan.

- RR trains would be discontinued south of City Hall, as the station would permanently become a terminal. The City Hall station is located one block east of Hudson Terminal. The segment between City Hall in Manhattan and Bay Ridge–95th Street would be replaced by two other services.

- B Sixth Avenue express trains would be rerouted to the Eighth Avenue Lines, replacing the AA and CC Eighth Avenue locals. B trains would run south through the connection and continue through the Montague Street Tunnel and BMT Fourth Avenue Line, thereby replacing the RR between Cortlandt Street in Manhattan and 59th Street in Brooklyn.

- JJ trains would operate via the Montague Street Tunnel and Fourth Avenue line, with an extension to Bay Ridge–95th Street.

- A Second Avenue Subway would operate along Second Avenue in Manhattan, connecting New Jersey with both Queens and the Bronx.

- T and Y would run the entire length of the Second Avenue line from New Jersey, then run toward Queens and the Bronx respectively.

- EE trains would be rerouted onto the southernmost section of the subway into New Jersey via the BMT Broadway express tracks, which turn eastward toward the Manhattan Bridge. The EE would then diverge southward, merging with the Second Avenue main line.

1986

editIn 1986, the Regional Plan Association suggested extending the IRT Flushing Line across the Hudson River to the Meadowlands Sports Complex in East Rutherford, New Jersey.[16]

In 1986, the MTA issued a study on expanding transit options on the west side of Manhattan. It was proposed to use the West Side Line viaduct (today's High Line), and various means of transportation were proposed, including monorail, passenger rail trains, or subway trains. It also proposed to extend the IRT Flushing or BMT Canarsie Lines (7 and <7> and L, respectively).[82]

1990

editIn 1990, the MTA proposed a rail line connecting LaGuardia Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport. The line would have operated over the Grand Central Parkway and the Van Wyck Expressway. There would be stations at Shea Stadium and Jamaica. The system was proposed to cost $2 billion. The MTA estimated that the rail link would take 30 minutes from Kennedy to LaGuardia, and the frequency of service would initially be every 15 minutes. There would be a two-track alignment with one track for each direction, as well as at least two trains heading in each direction at all times. If the link were built, the average travel time from Manhattan to Kennedy would have been about 45 minutes using the Long Island Rail Road, including transfers. To LaGuardia, the average travel time from the Grand Central station using the IRT Flushing Line would be 47 minutes.[83]

1998–99

editIn 1998, an extension of the BMT Astoria Line to LaGuardia Airport was planned, but the plan was canceled in 2003 following community opposition.[84][85]