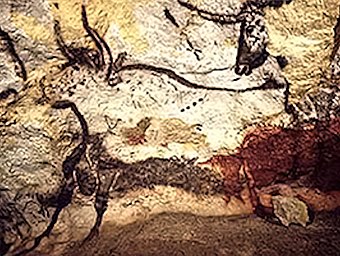

Art of a painted animal at Lascaux[1]

|

Proto-writing consists of visible marks communicating limited information.[2] Such systems emerged from earlier traditions of symbol systems in the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium BC in China and southeastern Europe. They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols or both to represent a limited number of concepts, in contrast to true writing systems, which record the language of the writer.[3]

Paleolithic

editAnalysis in 2022, led by Bennet Bacon, an amateur archaeologist,[4] showed that lines, dots and "Y"-like symbols on Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings were used to indicate the mating cycle of animals in a lunar calendar. The markings found in over 400 caves across Europe were compared to the mating cycles of the animals with which they were associated, showing a correlation with the month of the year in which the animals depicted in the cave paintings would typically give birth. The markings were 20,000 years old, predating any other equivalent writing systems by 10,000 years.[1][5]

Neolithic

editNeolithic China

editIn 2003, turtle shells with carved inscriptions featuring a library of symbols were found in 24 Neolithic graves excavated at Jiahu in the northern Chinese province of Henan. Using radiocarbon dating, the inscriptions have been dated to the 7th millennium BC. According to some archaeologists, the symbols bear a resemblance to the first attested oracle bone inscriptions dating to c. 1200 BC.[8] Others have dismissed this claim as insufficiently substantiated, claiming that simple geometric designs such as those found on the Jiahu shells cannot be linked to early writing.[9]

Neolithic Southeastern Europe

editThe Vinča symbols (6th–5th millennia BC) are an evolution of simple symbols first attested during the 7th millennium BC). Over time, the symbols gradually became more complex, ultimately culminating in the Tărtăria tablets (c. 5300 BC).[10]

Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age

editDuring c. 3600 – c. 3200 BC, proto-writing in the Fertile Crescent was gradually evolving into cuneiform, the earliest mature writing system.

Mesopotamia

editThe Kish tablet (c. 3500 BC) reflects the stage of proto-cuneiform, when what would become the cuneiform script of Sumer was still in the proto-writing stage. By the end of the 4th millennium BC, this symbol system had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a round-shaped stylus impressed into soft clay at different angles for recording numbers on clay tablets and accounting tokens. This was gradually augmented with pictographic writing using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted. The transitional stage to a writing system proper takes place in the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100 BC – c. 2900 BC).[citation needed]

Egypt

editA similar development took place in the genesis of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Various scholars believe that Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and ... probably [were] ... invented under the influence of the latter ...",[11] although it is pointed out and held that "the evidence for such direct influence remains flimsy" and that "a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt ..."[12]

Bronze Age

editDuring the Bronze Age, the cultures of the Ancient Near East are known to have had fully developed writing systems, while the marginal territories affected by the Bronze Age, such as Europe, India and China, remained in the stage of proto-writing.[citation needed]

The Chinese script emerged from proto-writing in the Chinese Bronze Age, during about the 14th to 11th centuries BC (Oracle bone script), while symbol systems native to Europe and India are extinct and replaced by descendants of the Semitic abjad during the Iron Age.[citation needed]

Indian Bronze Age

editThe Indus script is a symbol system that emerged during the end of the 4th millennium BC in the Indus Valley Civilisation.

European Bronze Age

editWith the exception of the Aegean and mainland Greece (Linear A, Linear B, Cretan hieroglyphs), the early writing systems of the Near East did not reach Bronze Age Europe. The earliest writing systems of Europe arise in the Iron Age, derived from the Phoenician alphabet.

However, there are number of interpretations regarding symbols found on artefacts of the European Bronze Age which amount to interpreting them as an indigenous tradition of proto-writing. Of special interest in this context are the Central European Bronze Age cultures derived from the Beaker culture in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. Interpretations of the markings of the bronze sickles associated with the Urnfield culture, especially the large number of so-called "knob-sickles" discovered in the Frankleben hoard, are discussed by Sommerfeld (1994).[13] Sommerfeld favours an interpretation of these symbols as numerals associated with a lunar calendar.[14][full citation needed]

Later proto-writing

editEven after the Bronze Age, several cultures have gone through a period of using systems of proto-writing as an intermediate stage before the adoption of writing proper. The "Slavic runes" (7th/8th century) mentioned by a few medieval authors may have been such a system. Another example is the system of pictographs invented by Uyaquk before the development of the Yugtun syllabary (c. 1900).[citation needed]

African Iron Age

editNsibidi is a system of symbols indigenous to what is now southeastern Nigeria. While there remains no commonly accepted exact date of origin, most researchers agree that use of the earliest symbols date back between the 5th and 15th centuries.[15][16] There are thousands of Nsibidi symbols which were used on anything from calabashes to tattoos and to wall designs. Nsibidi is used for the Ekoid and Igboid languages, and the Aro people are known to write Nsibidi messages on the bodies of their messengers.[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Bacon, Bennett; Khatiri, Azadeh; Palmer, James; Freeth, Tony; Pettitt, Paul; Kentridge, Robert (5 January 2023). "An Upper Palaeolithic Proto-writing System and Phenological Calendar". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 33 (3): 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0959774322000415. S2CID 255723053.

- ^ Robinson, Andrew (2009). Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-956778-2.

- ^ Gross, Michael (4 December 2012). "The evolution of writing". Current Biology. 22 (23): R981–R984. Bibcode:2012CBio...22.R981G. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.032. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 23346575.

- ^ "Londoner solves 20,000-year Ice Age drawings mystery". BBC News. 2023-01-05. Retrieved 2023-01-05.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah (January 5, 2023). "Amateur archaeologist uncovers ice age 'writing' system". The Guardian. France. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Helen R. Pilcher 'Earliest handwriting found? Chinese relics hint at Neolithic rituals', Nature (30 April 2003), doi:10.1038/news030428-7 "Symbols carved into tortoise shells more than 8,000 years ago ... unearthed at a mass-burial site at Jiahu in the Henan Province of western China".

- ^ Li, X., Harbottle, G., Zhang, J. & Wang, C. 'The earliest writing? Sign use in the seventh millennium BC at Jiahu, Henan Province, China'. Antiquity, 77, 31–44, (2003).

- ^ "Archaeologists Rewrite History". China Daily. 12 June 2003..

- ^ Houston, Stephen D. (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. pp. 245–6. ISBN 978-0-521-83861-0.

- ^ Haarmann, Harald: "Geschichte der Schrift", C.H. Beck, 2002, ISBN 3-406-47998-7, p. 20

- ^ Geoffrey Sampson, Writing Systems: a Linguistic Introduction, Stanford University Press, 1990, p. 78.

- ^ Simson Najovits, Egypt, Trunk of the Tree: A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Algora Publishing, 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Christoph Sommerfeld, "Die Sichelmarken" in: Gerätegeld Sichel. Studien zur monetären Struktur bronzezeitlicher Horte im nördlichen Mitteleuropa, Vorgeschichtliche Forschungen vol. 19, Berlin/New York, 1994, ISBN 3-11-012928-0, pp. 207–264.

- ^ Sommerfeld (1994:251)

- ^ Slogar, Christopher (Spring 2007). "Early ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria: Towards a history of Nsibidi". African Arts. 40 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1162/afar.2007.40.1.18. JSTOR 20447809. S2CID 57566625.

- ^ Slogar, Christopher (2005). Iconography and Continuity in West Africa: Calabar Terracottas and the Arts of the Cross River Region of Nigeria/Cameroon (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Maryland. pp. 58–62. hdl:1903/2416.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gregersen, Edgar A. (1977). Language in Africa: an introductory survey. CRC Press. p. 176. ISBN 0-677-04380-5.