The Paulet affair, also known as British Hawaii, was the unofficial five-month 1843 occupation of the Hawaiian Islands by British naval officer Captain Lord George Paulet, of HMS Carysfort. It was ended by the arrival of American warships sent to defend Hawaii's independence. The British government in London did not authorize the move and it had no official status.

Provisional Cession of the Hawaiian or Sandwich Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 February – 31 July 1843 | |||||||||

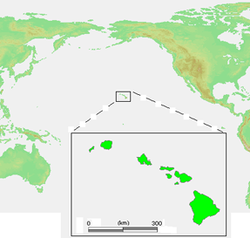

Location of the Hawaiian islands. | |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized and unapproved dependency of the United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Honolulu | ||||||||

| Common languages | English, Hawaiian | ||||||||

| Government | Military occupation, British colony | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1843 | Queen Victoria | ||||||||

| Local Representative | |||||||||

• 1843 | George Paulet | ||||||||

• 1843 | Richard Thomas | ||||||||

| Historical era | International relations | ||||||||

• Established | 25 February 1843 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 31 July 1843 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

British occupation

editPaulet became captain of HMS Carysfort on 28 December 1841, serving on the Pacific Station under Rear-Admiral Richard Darton Thomas (1777–1857).[1]

Richard Charlton, who had been the British consul to the Kingdom of Hawaii since 1825 met Paulet off the coast of Mexico in late 1842. Charlton claimed that British subjects in the Hawaiian Islands were being denied their legal rights. In particular, Charlton claimed land that was under dispute.[2] Paulet requested permission from Rear-Admiral Thomas to investigate the allegations.[3]

Paulet arrived at Honolulu and requested an audience with King Kamehameha III on 11 February 1843. He was told the King was on another island and would take six days to arrive. His next letter on 16 February maintained the polite tone of formal diplomatic correspondence, but was more demanding:

I have the honour to acquaint your Majesty of the arrival in this port of Her Britannic Majesty's ship under my command, and according to my instructions I am desired to demand a private interview with you, to which I shall proceed with a proper and competent interpreter.[4]

The King replied that American Gerrit P. Judd, as chief government minister, could be trusted to handle any written communication. This seemed to infuriate Paulet who had been told by Charlton that Judd was acting as "dictator". Paulet refused to speak with Judd, and accused him of fabricating the previous response. Paulet then listed specific demands.

Paulet warned Captain Long of an American ship, USS Boston on 17 February:

Sir, I have the honour to notify you that Her Britannic Majesty's Ship Carysfort, under my command, will be prepared to make an immediate attack upon this town, at 4 o'clock P.M. to-morrow, (Saturday) in the event of the demands now forwarded by me to the King of these Islands not being complied with by that time.

Sir, I have the honour to be your most obedient humble servant, George Paulet, captain[4]

Boston did not interfere.[5]

On 18 February the Hawaiian government wrote back that they would comply with the demands under protest, and hoped that a diplomatic mission already in London could settle any conflicts. Between the 20th and 23rd daily meetings were held by Alexander Simpson, acting consul and Paulet with the King. Kamehameha III agreed to reopen the disputed cases but refused to overrule the courts and ignore due process. On 25 February the agreement was signed ceding the land subject to any diplomatic resolution. Paulet appointed himself and three others to a commission to be the new government, and insisted on direct control of all land transactions.[4]

Paulet destroyed all Hawaiian flags he could find, and raised the British Union Flag for an occupation that would last six months. He cleared 156 residents off of the contested Charlton land. The dispute took years to resolve.[6]

-

King Kamehameha III confers with his Privy Council. At left is William Richards and Gerrit P. Judd sitting across from Robert Crichton Wyllie.

American intervention

editJames F. B. Marshall, an American merchant of Ladd and Company was invited aboard Boston where he secretly met Hawaiian Kingdom minister Judd. Judd gave Marshall an emergency commission as "envoy extraordinary" and sent him to plead the case for an independent Hawaii in London. Paulet closed down all shipping, but wanted to send Alexander Simpson back to England so that his side of the case could be heard first. Paulet rechristened the Hawaiian ship Hoikaika as Albert, and both Simpson and Marshall (telling Paulet he was only on a business mission) sailed to San Blas, Mexico. On 12 April they left overland and reached Veracruz by 1 May. Simpson continued to England, while Marshall went by ship and train to Boston by 2 June. He spread the news in the American press, and on 4 June, met with fellow Bostonians such as U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster and business partner and future minister to Hawaii Henry A. Peirce. Webster gave him letters for Edward Everett who was the American ambassador.[7]

On 30 June Marshall arrived in London and met with Everett. Two other envoys from Hawaii, William Richards and Timothy Haʻalilo were in Paris, France negotiating treaties. They had received verbal assurance that Hawaii's independence would be respected.[7] On April 1, 1843, Lord Aberdeen, the foreign minister on behalf of the Queen, assured the Hawaiian delegation that:

Her Majesty's Government was willing and had determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign.[8]

The USS Constellation arrived in Honolulu under Commodore Lawrence Kearny in early July. Acting American agent William Hooper protested the takeover to Kearny.[9] American Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones arrived with the USS United States on 22 July. He landed in Hilo where he consulted with American missionary Titus Coan. Rear-Admiral Thomas heard conflicting reports about the surprising developments in Hawaii. He had also heard how Jones had briefly occupied Monterey, California. Some historians think he was trying to defuse the situation before it spiraled into a larger conflict.[10]

On 26 July Rear-Admiral Thomas sailed into Honolulu harbor on his flagship HMS Dublin and requested an interview with the king. Kamehameha was more than happy to tell his side of the story. On 31 July, with the arrival of American warships, Thomas informed Kamehameha III the occupation was over. He reserved the right to protect British citizens, but respected the sovereignty of the Kingdom. The site of a ceremony raising the flag of Hawaii was made into a park in downtown Honolulu named Thomas Square in his honor.[11] The pathways are shaped in the form of the British flag. 31 July is celebrated as Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea or Restoration Day holiday.[12] A phrase from the speech made by Kamehameha III became the motto of Hawaii, and is included on the coat of arms and Seal of Hawaii: Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono, roughly translated from the Hawaiian language into English as "The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness."[11] Jones tried to hasten the peace process by inviting British officers to dinners, and celebrations including the restored king.[10]

References

edit- ^ "Biography of George Paulet R.N." Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ "The Charlton Land Claim". state archives centennial collection. state of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ Richard MacAllan (1966). "Richard Charlton: A Reassessment". Hawaiian Journal of History. Vol. 30. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 53–76. hdl:10524/266.

- ^ a b c "Correspondence relating to the Provisional Cession of the Sandwich Islands to great Britain.—February 1843". British and foreign state papers, Volume 150, Part 1. Great Britain Foreign Office. 1858. pp. 1023–1029. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017.

- ^ "The U.S. Navy in Hawaii, 1826–1945: An Administrative History". United States Navy. 1945. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Richard A. Greer (1998). "Along the Old Honolulu Waterfront". Hawaiian Journal of History. Vol. 32. pp. 53–66. hdl:10524/430.

- ^ a b James F. B. Marshall (1883). "An unpublished chapter of Hawaiian History". Harper's magazine. Vol. 67. pp. 511–520. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- ^ See "La Ku'oko'a: Events Leading to Independence Day, November 28, 1843" The Polynesian (November 2000) online

- ^ "A resolution of the Senate of February 25, 1845 in reference to the correspondence between the commander of the East India squadron and foreign powers". First session of the 29th Congress. Congress of the United States of America. 17 February 1846. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018.

- ^ a b Frank W. Gapp (1985). ""The Kind-Eyed Chief": Forgotten Champion of Hawaii's Freedom". Hawaiian Journal of History. Vol. 19. pp. 101–121. hdl:10524/235.

- ^ a b Dorothy Riconda (23 March 1972). "Thomas Square nomination form". National Register of Historic Places. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ Blaine Fergerstrom (30 June 2008). "Lā Ho'iho'i Ea / Restoration Day". Hawaii State Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

Further reading

edit- Kuykendall, Ralph S. (2021) [1947]. "XIII. 'The Paulet Episode'". The Hawaiian Kingdom. Vol. 1: Foundation and Transformation, 1778–1854. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 206–226. ISBN 978-0-87022-431-7. OCLC 414551.

- Siler, Julia Flynn (2013). The Lost Kingdom. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-9488-6.

- Simpson, Alexander (1843). The Sandwich Islands: progress of events since their discovery by Captain Cook. Their occupation by Lord George Paulet. Their value and importance. Smith, Elder.