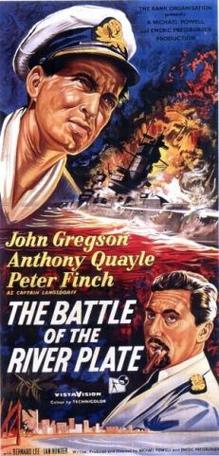

The Battle of the River Plate (a.k.a. Pursuit of the Graf Spee in the United States) is a 1956 British war film in Technicolor and VistaVision by the writer-director-producer team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. The film stars John Gregson, Anthony Quayle, Bernard Lee and Peter Finch. It was distributed worldwide by Rank Film Distributors Ltd.

| The Battle of the River Plate (Pursuit of the Graf Spee) | |

|---|---|

US release Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Powell Emeric Pressburger |

| Written by | Michael Powell Emeric Pressburger |

| Produced by | Michael Powell Emeric Pressburger |

| Starring | John Gregson Anthony Quayle Peter Finch |

| Narrated by | David Farrar |

| Cinematography | Christopher Challis |

| Edited by | Reginald Mills |

| Music by | Brian Easdale |

| Distributed by | Rank Film Distributors Ltd. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £275,348[1][2] |

| Box office | $750,000 (US)[3] |

The film's storyline concerns the Battle of the River Plate, an early World War II naval engagement in 1939 between a Royal Navy force of three cruisers and the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee.

Plot

editIn the early months of the Second World War, Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine sends out merchant raiders to attack Allied shipping. The British Royal Navy responds with hunting groups whose mission is to stop these attacks. In time, the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee is discovered in the Atlantic, just off South America, by a trio of British cruisers. With its speed and destructive firepower, Graf Spee is a formidable menace. Nevertheless, the British go straight into attack, closing swiftly to minimise the Graf Spee's substantial advantage in gun range. The British use their superior numbers to split her fire by attacking from different directions. But Graf Spee, under Captain Hans Langsdorff (Peter Finch), inflicts much damage on her foes. One of them, HMS Exeter, is particularly hard hit and is forced to retire to the Falklands for repair.

For her own part, the Graf Spee sustains some damage and takes refuge in the neutral port of Montevideo, Uruguay, for repairs. According to international law, the ship may remain in a neutral harbour only long enough to repair for seaworthiness, not to refit for battle; any overstay will lead to the ship and its crew being interned for the duration of the war. The British initially demand the Uruguayan authorities send Graf Spee out to sea within 24 hours, but once they recognise that reinforcements can arrive for an impending second battle they change strategy and lobby for an extension for the Germans. In reality the most powerful British ships are still extremely distant, but local media spreads false reports that more Royal Navy warships have arrived, including battleships and aircraft carriers; in fact, only three cruisers (Exeter having been replaced by HMS Cumberland) lie in wait.

Taken in by the ruse, Langsdorff takes his ship out with a skeleton crew aboard. As the onlookers watch from shore, she heads down the River Plate for the open sea and then bursts into flames from a series of explosions. It is obvious that Langsdorf has ordered that his ship be scuttled. This is a relief to the Royal Navy fleet, which reports, "Many a life has been saved today". At story's end, Langsdorff is personally complimented by the British for his humane decision.

Cast

editAt sea

edit- Peter Finch as Captain Hans Langsdorff, Admiral Graf Spee

- Bernard Lee as Captain Patrick Dove, MS Africa Shell

- Andrew Cruickshank as Captain William Stubbs,[4] SS Doric Star

- Peter Dyneley as Captain John Robison,[5] SS Newton Beech

- Anthony Quayle as Commodore (later Rear-Admiral) Henry Harwood, HMS Ajax

- Ian Hunter as Captain Charles Woodhouse, HMS Ajax

- Julian Somers as Quartermaster of Admiral Graf Spee

- Patrick Macnee as Lieutenant Commander Ralph Medley,(Macnee served in the Royal Navy during the War)[6] HMS Ajax

- John Gregson as Captain Frederick "Hookie" Bell, HMS Exeter (Gregson served in the Royal Navy during the War)

- Jack Gwillim as Captain Edward Parry, HMS Achilles (Gwillim served 20 years in the Royal Navy, rising to the rank of Commander)

- John Le Mesurier as the Chaplain of HMS Exeter (minor role)

- Donald Moffat as Able Seaman Swanston, HMS Ajax (uncredited)

- Barry Foster as Able Seaman Roper, HMS Exeter (uncredited)

Ashore

edit- Lionel Murton as Mike Fowler, American radio reporter in Montevideo

- Christopher Lee as Manolo, bar owner in Montevideo harbour

- Edward Atienza as Pop, Mike Fowler's gaucho assistant

- April Olrich as Dolores (singing voice by Muriel Smith)

- Anthony Bushell as Eugen Millington-Drake, the British Minister in Uruguay

- Michael Goodliffe as Captain Henry McCall,[7] British Naval Attaché in Buenos Aires

- Peter Illing as Dr Alberto Guani, Uruguayan Foreign Minister

- William Squire as Ray Martin, British SIS agent in Montevideo

- John Chandos as Dr Otto Langmann, the German Minister in Uruguay

- Douglas Wilmer as M. Desmoulins, the French Minister in Uruguay

- Roger Delgado as Captain Varela, Uruguayan Navy

- Cast notes

- Future director John Schlesinger has a small part as the German naval officer escorting Dove at the beginning of the film,[8] as does Captain Patrick Dove of Africa Shell, who is himself portrayed by Bernard Lee.

- Anthony Newley has a small part as a radio operator. Donald Moffat and Barry Foster, both uncredited, were making their film debuts, as was Jack Gwillim.

Production

editThe Battle of the River Plate had its genesis in an invitation to Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger to attend a film festival in Argentina in 1954. They decided they could not afford to take the time from their schedules unless it was a working holiday, and used the trip to research the defeat of Admiral Graf Spee. They came across the "hook" for their story when one of the surviving British naval officers gave Pressburger a copy of Captain Patrick Dove's book I Was Graf Spee's Prisoner, published in 1940.,[9] which became the basis of the human story of the film.[10]

Principal photography began on 13 December 1955, the 16th anniversary of the battle. The HMS Ajax and River Plate Association reportedly sent a message to the producers: "Hope your shooting will be as successful as ours". Location shooting for the arrival and departure of Admiral Graf Spee took place at the port of Montevideo, using thousands of locals as extras.[10] However, the scenes showing Admiral Graf Spee sailing from Montevideo were shot in the Grand Harbour at Valletta in Malta, and the launch taking McCall out to HMS Ajax was filmed in Mġarr harbour on Gozo, Malta's northern island.[citation needed]

Two songs written by composer Brian Easdale were used in the film, "Dolores' Song" and "Rio de la Plata". Both were acted by April Olrich as "Dolores", with singing voice dubbed by Muriel Smith.[11]

Ships used

edit- Admiral Graf Spee played by heavy cruiser USS Salem which retained its USN bow number, 139, for the film. This was explained by Captain Langsdorff as part of its camouflage to confuse other ships. One of three heavy cruisers of the Des Moines-class, she is now a museum ship in Massachusetts.

- Supply ship Altmark played by the fleet oiler RFA Olna

- HMS Ajax, flagship, played by HMS Sheffield

- HMS Exeter played by HMS Jamaica

- HMNZS Achilles played by herself (at the time in service with the Indian Navy as INS Delhi)

- HMS Cumberland played by herself when she joins the British squadron after the battle, (and by HMS Jamaica in the final scenes off Montevideo)

- German freighter Tacoma, which took the crew off Admiral Graf Spee before scuttling, played by RFA Fort Duquesne

- Gunboat Uruguay, boarding the Tacoma, was played by a British Ton-class minesweeper

- HMS Birmingham used for the firing of some of the guns, and to depict the explosions on the foredeck of Exeter, and as Admiral Graf Spee during the replenishment scene with Altmark, as well as the scene on the deck of Admiral Graf Spee showing the flag-draped coffins of dead German sailors laid out for burial in Montevideo

- Destroyers HMS Battleaxe and USS William R. Rush used as camera ships. The latter remained in service for many decades after the film, not being scrapped until 2016 after being transferred to the South Korea Navy in 1978.

Most of the action of the battle and prior to it takes place on real ships at sea. The producers had the advantage of having elements of the Mediterranean Fleet of the Royal Navy available for their use, and USS Salem to play the part of Admiral Graf Spee, although she had a different number of main turrets. The producers did make use of a 23-foot (7.0 m) model of Salem (with details only on the side being shot) in a six-foot (1.8 m)-deep tank at Pinewood Studios for scenes depicting hits during the battle, and also for the blowing-up of Admiral Graf Spee, which was assembled from multiple takes from different angles.[10]

In an early scene, it is claimed that Admiral Graf Spee is being disguised by the ship's carpenters – using features such as a false funnel – as an American cruiser, a trick typical of commerce raiders.[12][13] The US Navy would not allow any Nazi insignia to be displayed on Salem so the wartime German flag being hoisted and flown was filmed on a British ship. This is also the explanation as to why the crew of Admiral Graf Spee are seen wearing US Navy pattern helmets rather than German "Coal Scuttles" – whilst the filmmakers wanted to achieve an accurate impression and use German helmets they were refused permission. This aspect is sometimes described as a "goof" on the part of the filmmakers, but was in fact a circumstance beyond their control. Mention is made of Graf Spee's sister ships, Admiral Scheer and Deutschland. Admiral Scheer capsized after an air raid in 1945 and the remains of the wreck buried under a new harbor. Deutschland was renamed Lutzow in 1940 and sunk as a target in 1947.

Two of the original ships, HMNZS Achilles and HMS Cumberland were available for filming 15 years after the events depicted. Cumberland was a disarmed trial ship without her 8-inch gun turrets at this time and was refitted with lattice masts, but is recognizable as the last of the three-funneled heavy cruisers to remain in service. (In the final scenes, Jamaica represented Cumberland as one of the British trio waiting off Montevideo). This use of real warships was in line with an Admiralty policy of co-operation with film-makers, which saw the corvettes HMS Coreopsis and HMS Portchester Castle reactivated in 1952 for the film version of The Cruel Sea; the cruiser HMS Cleopatra and the minelayer HMS Manxman used in the 1953 film Sailor of the King, and the destroyer HMS Teazer and frigate Amethyst used in the 1955 film Yangtse Incident: The Story of H.M.S. Amethyst.

Achilles had been sold to the newly formed Indian Navy in 1948, becoming INS Delhi. The flagship HMS Ajax was her sister ship, and would have looked identical to Achilles, while the original HMS Exeter was a two-funnelled half-sister of Cumberland. HMS Sheffield and HMS Jamaica, which played Ajax and Exeter, had higher superstructures and more guns, which were mounted in triple turrets. Though different from the ships they represented, both these light cruisers had played a major part in the wartime campaign against the large German surface raiders which began at the Battle of the River Plate, including Bismarck in 1941, Admiral Hipper in 1942, Scharnhorst in 1943, and Tirpitz in 1944.

Historical details

editThe use of real ships allows the film to pay particular attention to detail even though Admiral Graf Spee was portrayed by the American heavy cruiser USS Salem, which mounted 3" smaller main guns, is considerably greater in tonnage, 100' longer, and quite visually distinct (in bow, shearline, and having two forward triple turrets instead of the single forward turret of the Deutschland-class cruisers) from the German Pocket Battleship. This emphasis on realism includes the warning bells ringing before each salvo, the scorching on the gun barrels after the battle, and the accurate depiction of naval procedures. The film depicts Admiral Graf Spee and Altmark using the complex procedure of alongside refueling; actually the Germans used the slower but safer method of astern refuelling, but the alongside method is much more dramatic for film purposes, and by 1955 was standard procedure for the British ships involved (see list above). Similarly, although the scene when Harwood meets with his captains on board Ajax is fictional, it was created for the movie in order to explain the tactical situation to the audience. The battle is seen from the perspective of the British ships, and that of the prisoners captured from nine merchantmen and held in Admiral Graf Spee.

The film devotes nearly 20 minutes to the battle, which actually lasted a little more than an hour before becoming a chase into Montevideo. The initial minutes from the spotting of Admiral Graf Spee at 0614, to her opening fire at 0618, and the British ships returning fire from 0620 are depicted in real time. In reality German gunfire did not "straddle" Exeter until 0623, after three salvoes, and her main armament fire was not "split" between the British ships until 0630, although these events are shown happening immediately. Exeter's bridge and forward turrets were knocked out at 0630, but at this point the film begins to telescope the sequence of events.[citation needed]

Commodore Harwood is shown wearing the sleeve rings of a rear admiral from the start, although he was only promoted to this rank after the battle. This is historically correct, as 'Commodores of the first class' wore those insignia at the time. Exeter's chaplain is also correctly depicted wearing a civilian dark suit and clerical collar; it was not until later in the war that naval chaplains adopted military uniform as a security measure.[citation needed]

The Battle of the River Plate only obliquely hints at one aspect of the story: the death of Captain Hans Langsdorff after he scuttled his ship. In the film Langsdorff is shown as subdued and depressed afterwards. In reality he was taken ashore to the Naval Hotel in Buenos Aires, where he wrote letters to his family and superiors. He then lay atop Admiral Graf Spee's battle ensign and shot himself,[14] forestalling allegations that he had avoided further battle action through cowardice; another motivation was his desire, as Admiral Graf Spee's captain, to symbolically go down with his ship. He was talked out of this by his officers, who convinced him that his leadership was still needed in seeking amnesty for his crew.[citation needed] Once their fate was decided, Langsdorff took his own life.

Captain Langsdorff was buried in the German section of the La Chacarita Cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina and was honoured by both sides in the battle for his honourable conduct.[citation needed] Prior to the destruction of the Graf Spee, the German crew were seen rowing away from the ship whereas in reality they were taken off by an Argentine tugboat. Also not shown is the use of certain captured merchant vessels as prizes, sailed by crews from Graf Spee to carry captured sailors, which were later sunk. In addition a Norwegian merchant ship reported the Graf Spee heading for South America before being spotted by lookouts but this is omitted. Furthermore the British Government secretly arranged for French and British merchant ships to leave Montevideo harbour every 24 hours to delay Graf Spee's departure. Also omitted is Graf Spee attempting to force a merchant ship to stop while she herself was being pursued by the British cruisers.

Release and reception

editWhen The Battle of the River Plate was completed and screened for executives at the Rank Organisation, it was received so well that it was decided to hold the release of the film for a year, so that it could be chosen as part of the next year's Royal Film Performance (in 1956), since 1955's film had already been selected. The royal premiere was held at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square (now Cineworld) on 29 October 1956 in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II, Princess Margaret, Marilyn Monroe, and Victor Mature.[15][16]

Box office

editThe film performed very well at the box office, being the fourth most popular film in Britain in 1957, after High Society, Doctor at Large and The Admirable Crichton.[10][17][18]

Critical opinion

editAt the time of The Battle of the River Plate's release, F. Maurice Speed writing in What's On In London described it as "Long, meticulous in its Naval detail, a little confusing sometimes to the landlubber like myself, [but] wonderfully photographed", adding that "some of the best scenes are the earlier quieter ones between Capt. Langsdorff (Graf Spee) and his prisoner Captain Dove (Bernard Lee). Finch, Lee, John Gregson (Capt. of the gallant "Exeter") and Anthony Quayle (of the "Ajax") all give performances above the average."[19]

Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic described The Battle of the River Plate as "almost unrelievedly dreadful".[20]

Honours

editThe Battle of the River Plate was nominated for three BAFTA Awards in 1957, for "Best British Film", "Best British Screenplay" and "Best Film From Any Source".[21]

Book

edit| Author | Michael Powell |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Nonfiction |

| Publisher | Hodder and Stoughton,[22] Rinehart (1956), White Lion Publishers (1976) |

Publication date | October 1956 (UK), 1957 (US), 1976 (second edition) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 0-7274-0256-0 |

In 1956 Powell published Graf Spee with Hodder and Stoughton, a.k.a. Death in the Atlantic (Rinehart, US), retelling the story of the film in more detail. In 1976, a second edition was released by White Lion Publishers with the amended title, The Last Voyage of the Graf Spee.

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 359 - the movie went slightly over budget

- ^ Macdonald, Kevin (1994). Emeric Pressburger: The Life and Death of a Screenwriter. Faber and Faber. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-571-16853-8.

- ^ "Rank-Yank Keeps Expanding". Variety. 16 July 1959. p. 13.

- ^ "Blue Star's S.S. Doric Star". BlueStarLine.org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "SS Roxby". Mercantile Marine Forum. February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ van der Vat, Dan (3 September 1999). "Obituary: Captain Ralph Medley". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2011 – via The Powell & Pressburger Pages.

- ^ Trueman, C. N. "The Graf Spee in Montevideo". History Learning Site. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ John Schlesinger (I) at IMDb

- ^ Dove, Patrick (1940). "I was Graf Spee's Prisoner, by Captain Patrick Dove".

- ^ a b c d Miller, Frank. "Pursuit of the Graf Spee (1957)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Pursuit of the Graf Spee (1956) Soundtracks". IMDb. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Asmussen, John. "Admiral Graf Spee in Disguise". Deutschland-class.dk. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Admiral Graf Spee". Maritimequest.com. 6 July 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Adam, Thomas (2005). "Admiral Graf Spee". Germany and the Americas. ABC-CLIO. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-85109-628-2. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- ^ "Her Majesty: a new book of photographs celebrating the life of Queen Elizabeth II". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "What happened when Queen Elizabeth met Hollywood royal Marilyn Monroe?". South China Morning Post. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Lindsay; Dent, David (8 January 1958). "Time For New Ideas". The Times. London. p. 9.

- ^ The Battle of the River Plate at IMDb

- ^ "Contemporary Review (What's On In London) - The Battle of the River Plate (1956)". powell-pressburger.org. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Arms and the Man". The New Republic. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Pursuit of the Graf Spee (1956) Awards". IMDb. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Graf Spee". Goodreads.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

Bibliography

edit- Christie, Ian. Arrows of Desire: the films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. London: Faber & Faber, 1994. ISBN 0-571-16271-1. 163pp (illus. filmog. bibliog. index).

- Pope, Dudley. The Battle of the River Plate. London: William Kimber, 1956. 259pp (illus).

- Powell, Michael. A Life in Movies: An Autobiography. London: Heinemann, 1986. ISBN 0-434-59945-X.

- Powell, Michael. Million Dollar Movie. London: Heinemann, 1992. ISBN 0-434-59947-6.

External links

edit- The Battle of the River Plate at IMDb

- The Battle of the River Plate at the BFI's Screenonline. Full synopsis, film stills and clips viewable from UK libraries

- Reviews and articles at the Powell & Pressburger Pages

- Pursuit of the Graf Spee at the TCM Movie Database

- Pursuit of the Graf Spee at AllMovie

- "The Battle of the River Plate" on YouTube