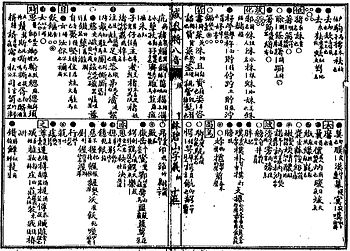

The Qi Lin Bayin, sometimes translated as Book of Eight Sounds or Book of Eight Tones, is a Chinese rime book of approximately ten thousand characters based on the earlier form of the Fuzhou dialect. First compiled in the 17th century, it is the pioneering work of all written sources for Min languages, and is widely quoted in modern academic research in Chinese phonology.

| Qi Lin Bayin | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Chinese | 戚林八音 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Composition

editThe Qi Lin Bayin is a combination of two dictionaries:

- Qī cānjūn bāyīn zìyì biànlǎn 戚參軍八音字義便覽 "Eight Sounds of General Qi and a Convenient Prospectus of Word Meaning", and

- Tàishǐ Lín Bìshān xiānshēng zhūyù tóngshēng 太史林碧山先生珠玉同聲 "Homonyms of Pearl and Jade by the Honorable Lin Bishan".[1][2]

The combined edition was published in 1749 by Jin An, a citizen of Fuzhou, who added a foreword.[1] As local works, the earlier dictionaries were largely ignored by the scholarly tradition, so inferences about their date and authorship are necessarily based on internal evidence.[3]

The Qī is named in honour of Qi Jiguang, a general who led a mission to evict pirates from Fujian between 1562 and 1567, and presumably dates from the late 16th century. However, it is unlikely that Qi himself was the author, as he was a native of Shandong and spent only a few years in the area, and the book is not mentioned in his official biography.[4] Luo Changpei and other scholars have suggested that the book was written or compiled by the scholar Chen Di, who served in Qi's army, and later made major contributions to Chinese philology.[4] However, there are numerous differences between the Qī and Chen's known works.[5] Most modern authors believe the book to be the work of one Cài Shìpàn (蔡士泮), who is credited in the dictionary with "collecting and editing" the work, but is otherwise unknown.[6][7]

The Lín appears to be patterned on the structure of the Qī. It is named in honour of Lín Bìshān (林碧山), a native of Minhou County who served as an official in Hebei shortly after passing the advanced examination in 1688. Although the book is believed to date from the end of the 17th century, Lin is not known to have produced any scholarly works.[8] As with the Qī, the Lín is attributed by most modern scholars to an otherwise-unknown person recorded as having edited it, Chén Tā (陳他).[6][9]

Tones, initials, and rimes

editTones

editThe tonal categories of Fuzhou dialect have remained stable since the time of Qī Lín Bāyīn. In the book title, Bāyīn (lit. eight sounds) denotes eight tones, whose names are: (1) 上平, (2) 上上, (3) 上去, (4) 上入, (5) 下平, (6) 下上, (7) 下去, and (8) 下入. But the sixth tone 下上 is actually identical with the second one 上上 and therefore exists in theory only. In other words, Fuzhou dialect has seven rather than eight tones, and the term Bāyīn is something of a misnomer.

However, due to the lack of phonetic descriptions of the seven tones, the deduction of the tonal values of that time is considered beyond possibility.

Initials

editIn Qī Lín Bāyīn, the fifteen initials are organized into a five-character shī (the last five characters "打掌與君知" are simply used to make up the four lines as a whole), as follows:[6][10]

柳邊求氣低, [l], [p], [k], [kʰ], [t] 波他曾日時, [pʰ], [tʰ], [ts], [n], [s] 鶯蒙語出非, null initial, [m], [ŋ], [tsʰ], [h] 打掌與君知.

In spite of the perceptible confluence of [n] and [l] in modern Fuzhou dialect, the initial structure nowadays is by and large the same as it was in the time of Qī Lín Bāyīn.

Rimes

editLikewise, a cí is built up in Qī Lín Bāyīn by all thirty-three rimes in the then Fuzhou dialect (three characters, "金", "梅" and "遮", are redundant), as follows:[6][11]

春花香, [uŋ/uk], [ua/uaʔ], [ioŋ/iok] 秋山開, [iu], [aŋ/ak], [ai] 嘉賓歡歌須金杯. [a/aʔ], [iŋ/ik], [uaŋ/uak], [o/oʔ], [y], redundant, [uoi] 孤燈光輝燒銀缸. [u/uʔ], [ɛŋ/ɛk], [uoŋ/uok], [ui], [ieu], [yŋ/yk], [oŋ/ok] 之東郊, [i], [øŋ/øk], [au] 過西橋. [uo/uoʔ], [ɛ/ɛʔ], [io/ioʔ] 雞聲催初天, [ie], [iaŋ/iak], [øy], [œ/œʔ], [ieŋ/iek] 奇梅歪遮溝. [ia/iaʔ], redundant, [uai], redundant, [ɛu]

The past couple of centuries witnessed three major changes in Fuzhou dialect. The first is the phenomenon of close/open rimes, by which the 上去, 上入 and 下去 characters shift its rime to its open form under certain circumstances; the second is the merger of [iu] and [ieu], as well as [ui] and [uoi]; and the last is the confusion of the codas [-k] and [-ʔ].

Role in early studies of Fuzhou dialect

editFor centuries, the Qi Lin Bayin had been used by local people as an authoritative reference on the Fuzhou pronunciation. It also greatly assisted the earliest Western missionaries in Fuzhou in learning and studying the native language.[12] The American Methodist missionary M.C. White published the first Western description of the Fuzhou dialect.[13] White based his account of the phonology directly on the Qi Lin Bayin, writing:

The system of initials and finals used in the 'Book of Eight Tones', would, if used for that purpose, form (in connection with the tonal marks) a complete alphabet for the Fuh Chau dialect. They have been so used by missionaries for writing colloquial phrases, in their private study of the language. Three of the gospels have been written out in this manner by Chinese teachers in the employment of missionaries.

— M.C. White[14]

To obtain a more convenient system than the Chinese characters naming the initials and finals, White spelled out each of them using the Latin-based alphabet devised by the English philologist Sir William Jones to represent languages of India, the Pacific and North America.[15] He thus produced the first published romanization of the language. The scheme consists of fourteen consonants (the null initial is not written) and nine vowels:[16][17]

- Consonants: ch, ch', h, k, k', l, m, n, ng, p, p', s, t, t'

- Vowels: a, e, è, ë, i, o, ò, u, ü

White's romanization was adjusted by later authors, and became standardized as Foochow Romanized (Bàng-uâ-cê) several decades later.

References

edit- ^ a b Yong & Peng (2008), p. 359.

- ^ Li (1993), p. 7.

- ^ Li (1993), pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Li (1993), p. 12.

- ^ Li (1993), pp. 23–25.

- ^ a b c d Yong & Peng (2008), p. 360.

- ^ Li (1993), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Li (1993), p. 27.

- ^ Li (1993), p. 28.

- ^ Li (1993), pp. 168–169.

- ^ Li (1993), pp. 43–45.

- ^ Li (1993), pp. 213–214.

- ^ Li (1993), p. 215.

- ^ White (1856), p. 354.

- ^ White (1856), p. 356.

- ^ White (1856), pp. 355–356.

- ^ Li (1993), p. 217.

- Li, Zhuqing (1993), A study of the "Qī Lín Bāyīn" (PhD thesis), University of Washington, OCLC 38703889.

- White, M.C. (1856), "The Chinese Language Spoken at Fuh Chau", The Methodist Review, 38: 352–381.

- Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008), Chinese Lexicography : A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911: A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-156167-2.