The Autonomous Republic of Crimea is an administrative division of Ukraine encompassing most of Crimea that was unilaterally annexed by Russia in 2014. The Autonomous Republic of Crimea occupies most of the peninsula,[4][5] while the City of Sevastopol (a city with special status within Ukraine) occupies the rest.

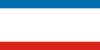

Autonomous Republic of Crimea

| |

|---|---|

Autonomous republic of Ukraine[a] | |

| Anthem: "Нивы и горы твои волшебны, Родина" (Russian)

Nivy i gory tvoi volshebny, Rodina (transliteration) Your fields and mountains are magical, Motherland | |

Location of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (red) before September 2023in Ukraine (light yellow) | |

Location of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (light yellow) in the Crimean Peninsula | |

| Autonomy | 12 February 1991 |

| Constitution | 21 October 1998 |

| Russian occupation | 20 February 2014[b] |

| Annexed by Russia | 18 March 2014[2] |

| Capital and largest city | Simferopol |

| Official languages | Ukrainian, Russian, Crimean Tatar[3] |

| Ethnic groups (2001) |

|

| Government | Autonomous republic |

| Tamila Tasheva | |

| Legislature | Supreme Assembly (suspended) |

| Area | |

• Total | 26,100 km2 (10,100 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2001 census | 2,033,700 |

• Density | 77.9/km2 (201.8/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | UA-43 |

The Cimmerians, Scythians, Greeks, Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Khazars, Byzantine Greeks, the state of Kievan Rus', Kipchaks, Italians, and Golden Horde Mongols[6] and Tatars each controlled Crimea in its earlier history. In the 13th century, it was partly controlled by the Venetians and by the Genoese, and in the late 15th century, it was partly under Polish suzerainty.[7] They were followed by the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire in the 15th to 18th centuries, the Russian Empire in the 18th to 20th centuries, Germany during World War II, and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and later the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, within the Soviet Union during the rest of the 20th century until Crimea became part of independent Ukraine with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

After the Revolution of Dignity in February 2014, Russian troops took control of the territory.[8] Russia formally annexed Crimea on 18 March 2014, incorporating the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol as the 84th and 85th federal subjects of Russia.[9] While Russia and 17 other UN member states recognize Crimea as part of the Russian Federation, Ukraine continues to claim Crimea as an integral part of its territory, supported by most foreign governments and United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262.[10]

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea is an autonomous parliamentary republic within Ukraine[4] and was governed by the Constitution of Crimea in accordance with the laws of Ukraine. The capital and administrative seat of the republic's government is the city of Simferopol, located in the centre of the peninsula. Crimea's area is 26,200 square kilometres (10,100 sq mi) and its population was 1,973,185 as of 2007. These figures do not include the area and population of the City of Sevastopol (2007 population: 379,200), which is administratively separate from the autonomous republic. The peninsula thus has 2,352,385 people (2007 estimate).

Crimean Tatars, a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority who in 2001 made up 12.10% of the population,[11] formed in Crimea in the late Middle Ages, after the Crimean Khanate had come into existence. The Crimean Tatars were forcibly expelled to Central Asia by Joseph Stalin's government. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Crimean Tatars began to return to the region.[12] According to the 2001 Ukrainian population census 58% of the population of Crimea are ethnic Russians and 24% are ethnic Ukrainians.[11] The region has the highest proportion of Muslims in Ukraine.[11]

Background

The Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established as part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1921, with the latter joining with other republics to form the Soviet Union. Following the end of Nazi occupation during World War II, indigenous Crimean Tatars were forcibly deported and the autonomous republic was abolished in 1945, replaced with an oblast-level jurisdiction. In 1954, Crimea Oblast was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Ukrainian SSR. Shortly prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Crimea was granted the status of Autonomous Republic by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR following a state-sanctioned referendum held on January 20, 1991. When Ukraine became independent, Crimea remained a republic within the country, leading to tensions between Russia and Ukraine as the Black Sea Fleet was based on the peninsula.

History

Post-Soviet years

Since Ukrainian independence, more than 250,000 Crimean Tatars have returned and integrated into the region.[13]

Between 1992 and 1995, a struggle about the division of powers between the Crimean and Ukrainian authorities ensued. On 26 February, the Crimean parliament renamed the ASSR the Republic of Crimea. Then on 5 May, it proclaimed self-government[14][15][16] and twice enacted constitutions that the Ukrainian government and Parliament refused to accept on the grounds that it was inconsistent with Ukraine's constitution.[17] Finally in June 1992, the parties reached a compromise: Crimea would be given the status of "autonomous republic" and granted special economic status, as an autonomous but integral part of Ukraine.[18]: 587

In October 1993, the Crimean parliament established the post of president of Crimea. Tensions rose in 1994 with election of separatist leader Yury Meshkov as Crimean president. On 17 March 1995, the parliament of Ukraine abolished the Crimean constitution of May 1992, all the laws and decrees contradicting those of Kyiv, and also removed Yuriy Meshkov, the then president of Crimea, along with the office itself.[19][20][21] After an interim constitution, the 1998 Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea was put into effect, changing the territory's name to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Formation of the autonomous republic

Following the ratification of the May 1997 Russian–Ukrainian Friendship Treaty, in which Russia recognized Ukraine's borders and sovereignty over Crimea, international tensions slowly eased. However, in 2006, anti-NATO protests broke out on the peninsula.[22] In September 2008, the Ukrainian foreign minister Volodymyr Ohryzko accused Russia of giving out Russian passports to the population in Crimea and described it as a "real problem" given Russia's declared policy of military intervention abroad to protect Russian citizens.[23]

On 24 August 2009, anti-Ukrainian demonstrations were held in Crimea by ethnic Russian residents. Sergei Tsekov (of the Russian Bloc[24] and then deputy speaker of the Crimean parliament)[25] said then that he hoped that Russia would treat Crimea the same way as it had treated South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[26] The 2010 Ukrainian–Russian Naval Base for Natural Gas treaty extended Russia's lease on naval facilities in Crimea until 2042, with optional five-year renewals.[27]

Occupation and annexation by Russia

Crimea voted strongly for the pro-Russian Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych and his Party of Regions in presidential and parliamentary elections,[28] and his ousting on 22 February 2014 during the 2014 Ukrainian revolution was followed by a push by pro-Russian protesters for Crimea to secede from Ukraine and seek assistance from Russia.[29]

On 28 February 2014, Russian forces occupied airports and other strategic locations in Crimea[30] though the Russian foreign ministry stated that "movement of the Black Sea Fleet armored vehicles in Crimea (...) happens in full accordance with basic Russian-Ukrainian agreements on the Black Sea Fleet".[citation needed] Gunmen, either armed militants or Russian special forces, occupied the Crimean parliament and, under armed guard with doors locked, members of parliament elected Sergey Aksyonov as the new Crimean prime minister.[31] Aksyonov then said that he asserted sole control over Crimea's security forces and appealed to Russia "for assistance in guaranteeing peace and calmness" on the peninsula. The interim government of Ukraine described events as an invasion and occupation[32][33] and did not recognize the Aksyonov administration as legal.[34][35] Ousted Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych sent a letter to Putin asking him to use military force in Ukraine to restore law and order.[citation needed] On 1 March, the Russian parliament granted president Vladimir Putin the authority to use such force.[36] Three days later, several Ukrainian bases and navy ships in Crimea reported being intimidated by Russian forces and Ukrainian warships were also effectively blockaded in Sevastopol.[37][38]

On 6 March, the Crimean parliament asked the Russian government for the region to become a subject of the Russian Federation with a Crimea-wide referendum on the issue set for 16 March. The Ukrainian government, the European Union, and the US all challenged the legitimacy of the request and of the proposed referendum as article 73 of the constitution of Ukraine states: "Alterations to the territory of Ukraine shall be resolved exclusively by an all-Ukrainian referendum."[39] International monitors arrived in Ukraine to assess the situation but were halted by armed militants at the Crimean border.[40][41]

The day before the referendum, Ukraine's national parliament voted to dissolve the Supreme Council of Crimea as its pro-Moscow leaders were finalising preparations for the vote.[42]

The 16 March referendum required voters to choose between "Do you support rejoining Crimea with Russia as a subject of the Russian Federation?" and "Do you support restoration of the 1992 Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Crimea's status as a part of Ukraine?" There was no option on the ballot to maintain the status quo.[43][44] However, support for the second question would have restored the republic's autonomous status within Ukraine.[20][45] The official turnout for the referendum was 83%, and the overwhelming majority of those who voted (95.5%)[46] supported the option of rejoining Russia. However, a BBC reporter claimed that a huge number of Tatars and Ukrainians had abstained from the vote.[47]

Following the referendum, the members of the Supreme Council voted to rename themselves the State Council of the Republic of Crimea and also formally appealed to Russia to accept Crimea as part of the Russian Federation.[48] This was granted and on 18 March 2014 the self-proclaimed Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession to the Russian Federation[49] though the accession was granted separately for each of the former regions that composed it: one accession for the Republic of Crimea, and another for Sevastopol as a federal city.[50] On 24 March 2014 the Ukrainian government ordered the full withdrawal of all of its armed forces from Crimea and two days later the last Ukrainian military bases and Ukrainian navy ships were captured by Russian troops.[51][52][c]

Ukraine, meanwhile, continues to claim Crimea as its territory and in 2015 the Ukrainian parliament designated 20 February 2014 as the (official) date of the start of "the temporary occupation of Crimea."[1] On 27 March 2014 100 United Nations member states voted for United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262 affirming the General Assembly's commitment to the territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders while 11 member states voted against, 58 abstained and 24 member states absented.[10] Since then six countries (Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Syria, Afghanistan, and North Korea) have publicly recognized Russia's annexation of Crimea while others have stated support for the 16 March 2014 Crimean referendum.[55]

Government and administration

Executive power in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea was exercised by the Council of Ministers of Crimea, headed by a Chairman, appointed and dismissed by the Supreme Council of Crimea, with the consent of the President of Ukraine.[56] Though not an official body, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People could address grievances to the Ukrainian central government, the Crimean government, and international bodies.[57]

An administrative reform, enacted by the Verkhovna Rada on 17 July 2020, envisages redivision of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea into 10 enlarged raions (districts), into which cities (municipalities) of republican significance will be absorbed. Originally the reform was delayed until return of the peninsula under Ukrainian control,[58][59][60] but it came into effect on 7 September 2023.[61] Since the reform, the following are the subdivisions of the republic:

- Bakhchysarai Raion (Bağçasaray rayonı) — composed of Bakhchysarai Raion and parts of territory that earlier was subordinated to the Sevastopol municipality (without the Sevastopol city proper and also without Balaklava as such that exists within the Sevastopol city limits within the framework of Ukrainian legislation),

- Bilohirsk Raion (Qarasuvbazar rayonı) — composed of Bilohirsk and Nyzhniohirsk raions,

- Dzhankoi Raion (Canköy rayonı) — composed of Dzhankoi Raion and former Dzhankoi municipality,

- Yevpatoria Raion (Kezlev rayonı) — composed of Saky and Chornomorske raions and former Yevpatoria and Saky municipalities,

- Kerch Raion (Keriç rayonı) — composed of Lenine Raion and former Kerch municipality,

- Kurman Raion (Qurman rayonı) — composed of Krasnohvardiysky and Pervomaisk raions,

- Perekop Raion (Or Qapı rayonı) — composed of Krasnoperekopsk and Rozdolne raions, former Armiansk and Krasnoperekopsk municipalities,

- Simferopol Raion (Aqmescit rayonı) — composed of Simferopol Raion and former Simferopol municipality,

- Feodosia Raion (Kefe rayonı) — composed of Kirovske and Sovietskyi raions, former Feodosia and Sudak municipalities,

- Yalta Raion (Yalta rayonı) — composed of former Yalta and Alushta municipalities.

Raion

Raion

Raion

Raion

Raion

Raion

Raion

Former divisions

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea had 25 administrative areas: 14 raions (districts) and 11 mis'kradas and mistos (city municipalities), officially known as territories governed by city councils.[62]

Raions

|

City municipalities |

Major centres of urban development:

See also

Notes

- ^ Annexed by Russia as the Republic of Crimea

- ^ In 2015 the Ukrainian parliament officially set 20 February 2014 as the date of "the beginning of the temporary occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia."[1]

- ^ (Also) on 24 March 2014, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense stated that approximately 50% of the Ukrainian soldiers in Crimea had defected to the Russian military.[53][54]

References

- ^ a b Twitter verifies account of Russia's MFA in Crimea, Ukraine files complaint, UNIAN (11 January 2019)

(in Ukrainian) "Nasha" Poklonsky promises to the "Berkut" fighters to punish the participants of the Maidan, Segodnya (20 March 2016) - ^ Toal, Gerald; O’Loughlin, John; M. Bakke, Kristin (18 March 2020). "Six years and $20 billion in Russian investment later, Crimeans are happy with Russian annexation Point". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Verkhovna Rada of Crimea. "Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea". pp. Section 1, Article 10. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

In the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, alongside with the official language, the application and development, use and protection of Russian, Crimean Tatar and other ethnic groups' languages shall be secured.

- ^ a b Regions and territories: The Republic of Crimea, BBC News

- ^ "Government Portal of The Autonomous Republic of Crimea". Kmu.gov.ua. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Kołodziejczyk, Dariusz (2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania. International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th–18th Century). A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by Annotated Documents. Leiden and Boston: Brill. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-04-19190-7.

- ^ "Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club". Kremlin.ru. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015.

I will be frank; we used our Armed Forces to block Ukrainian units stationed in Crimea

- ^ Распоряжение Президента Российской Федерации от 17.03.2014 № 63-рп 'О подписании Договора между Российской Федерацией и Республикой Крым о принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов'. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Kremlin: Crimea and Sevastopol are now part of Russia, not Ukraine". CNN. 18 March 2014.

- ^ a b c About number and composition population of Autonomous Republic of Crimea by data All-Ukrainian population census', Ukrainian Census (2001)

- ^ Pohl, J. Otto. The Stalinist Penal System: A Statistical History of Soviet Repression and Terror. Mc Farland & Company, Inc, Publishers. 1997. 23.

- ^ Gabrielyan, Oleg (1998). Крымские репатрианты: депортация, возвращение и обустройство (in Russian). Amena. p. 321.

- ^ Wolczuk, Kataryna (31 August 2004). "Catching up with 'Europe'? Constitutional Debates on the Territorial-Administrative Model in Independent Ukraine". Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieved 16 December 2006. [dead link]

Wydra, Doris (11 November 2004). "The Crimea Conundrum: The Tug of War Between Russia and Ukraine on the Questions of Autonomy and Self-Determination". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 10 (2): 111–130. doi:10.1163/157181104322784826. ISSN 1385-4879. - ^ "Ukraine President Claims New Powers in Crimea". The New York Times. 2 April 1995.

- ^ Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 1857431871 (page 540)

- ^ Russians in the Former Soviet Republics by Pål Kolstø, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 0253329175 (page 194)

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ^ "Ukraine Abolishes Crimea Constitution, Presidency : Black Sea: Measures taken by Kiev leadership give it broad powers over the violence-ridden peninsula". Los Angeles Times. 18 March 1995.

- ^ a b Belitser, Natalya (20 February 2000). "The Constitutional Process in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in the Context of Interethnic Relations and Conflict Settlement". International Committee for Crimea. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Laws of Ukraine. Verkhovna Rada law No. 93/95-вр: On the termination of the Constitution and some laws of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Adopted on 17 March 1995. (Ukrainian)

- ^ Russia tells Ukraine to stay out of Nato, The Guardian (8 June 2006)

- ^ Cheney urges divided Ukraine to unite against Russia 'threat Archived 21 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press. 6 September 2008.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (8 February 2007). "Ukraine: Kiev fails to end Crimea's ethnic tentions" (PDF). Oxford Analytica. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras. "Separatists and Russian nationalist-extremist allies of the Party of Regions call for union with Russia" (PDF). KyivPost. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ Levy, Clifford J. (28 August 2009). "Russia and Ukraine in Intensifying Standoff". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Update: Ukraine, Russia ratify Black Sea naval lease, Kyiv Post (27 April 2010)

- ^ Local government elections in Ukraine: last stage in the Party of Regions’ takeover of power Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Centre for Eastern Studies (4 October 2010)

- ^ "Putin orders military exercise as protesters clash in Crimea". Russia Herald. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "This is what it looked like when Russian military rolled through Crimea today (VIDEO)". UK Telegraph. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Shuster, Simon (10 March 2014). "Putin's Man in Crimea Is Ukraine's Worst Nightmare". Time. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

Before dawn on Feb. 27, at least two dozen heavily armed men stormed the Crimean parliament building and the nearby headquarters of the regional government, bringing with them a cache of assault rifles and rocket propelled grenades. A few hours later, Aksyonov walked into the parliament and, after a brief round of talks with the gunmen, began to gather a quorum of the chamber's lawmakers.

- ^ Charbonneau, Louis (28 February 2014). "UPDATE 2-U.N. Security Council to hold emergency meeting on Ukraine crisis". Reuters. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Higgons, Andrew, "Grab for Power in Crimea Raises Secession Threat", The New York Times, 28 February 2014, page A1; reporting was contributed by David M. Herszenhorn and Andrew E. Kramer from Kiev, Ukraine; Andrew Roth from Moscow; Alan Cowell from London; and Michael R. Gordon from Washington; with a graphic presentation of linguistic divisions of Ukraine and Crimea

- ^ Radyuhin, Vladimir (1 March 2014). "Russian Parliament approves use of army in Ukraine". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine army on full alert as Russia backs sending troops". BBC News. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Smale, Alison; Erlanger, Steven (1 March 2014). "Kremlin Clears Way for Force in Ukraine; Separatist Split Feared". New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "'So why aren't they shooting?' is Putin's question, Ukrainians say". Kyiv Post. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine resistance proves problem for Russia". BBC Online. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "'another view of the Ochakov – scuttled by Russian forces Wed night to block mouth of Donuzlav inlet". Twitter@elizapalmer. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "'Ukraine crisis: Crimea parliament asks to join Russia". BBC.com. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "'Ukraine crisis: 'Illegal' Crimean referendum condemned". BBC.com. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Ukraine Votes to Dissolve Crimean Parliament. NBC News. 15 March 2014

- ^ "'Приложение 1 к Постановлению Верховной Рады Автономной Республики Крым от 6 марта 2014 года No 1702-6/14" (PDF). rada.crimea.ua. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Gorchinskaya, Katya (7 March 2014). "Two choices in Crimean referendum: yes and yes". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Sasse, Gwendolyn (3 March 2014). "Crimean autonomy: A viable alternative to war?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Crimea referendum: Voters 'back Russian union'". BBC News. 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Do Crimea referendum figures add up?". BBC News. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Lawmakers in Crimea Move Swiftly to Split From Ukraine New York Times, accessed 26 December 2014

- ^ "Kremlin: Crimea and Sevastopol are now part of Russia, not Ukraine". CNN. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: Putin signs Crimea annexation". BBC.co.uk. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine orders Crimea troop withdrawal as Russia seizes naval base". CNN. 24 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) "Russian troops captured all Ukrainian parts in the Crimea", BBC Ukrainian (26 March 2014)

- ^ "Defense Ministry: 50% Of Ukrainian Troops in Crimea Defect To Russia". Ukrainian News Agency. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ Jonathan Marcus (24 March 2014). "Ukrainian forces withdraw from Crimea". BBC News. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ "These are the 6 countries on board with Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea", Business Insider, 31 May 2016.

- ^ Crimean parliament to decide on appointment of autonomous republic's premier on Tuesday Archived 6 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax Ukraine (7 November 2011)

- ^ Ziad, Waleed; Laryssa Chomiak (20 February 2007). "A lesson in stifling violent extremism". CS Monitor. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ Прийнято Постанову «Про утворення та ліквідацію районів». Інформаційне управління Апарату Верховної Ради України Опубліковано 17 липня 2020, о 13:02

- ^ Мінрегіон оприлюднив проекти майбутніх районів в Україні. Ще можливі зміни Про портал «Децентралізація»

- ^ Постанова Верховної Ради України «Про утворення та ліквідацію районів» 17 липня 2020 року № 807-IX

- ^ a b "Про внесення змін до деяких законодавчих актів України щодо вирішення окремих питань адміністративно-територіального устрою Автономної Республіки Крим". Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України (in Ukrainian). 23 August 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Автономна Республіка Крим [Autonomous Republic of Crimea]. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

Further reading

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- Alexeenko A.O., Balyshev M.A. (2017). Scientific and technical documentation on the economic situation of the Crimean region in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1954-1991) (review of sources from the funds of the Central State Scientific and Technical Archive of Ukraine). Archives of Ukraine, 2. P.103-113. (In Ukrainian)

External links

Official

- www.ppu.gov.ua, website of the Presidential Representative in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (in Ukrainian)

- ark.gp.gov.ua, website of the Prosecutor's Office of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (in Ukrainian)

Historical

- www.rada.crimea.ua, website of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (in Ukrainian and Russian)

- Series about the recent political history of Crimea by the Independent Analytical Centre for Geopolitical Studies "Borysfen Intel"