This article is largely based on an article in the out-of-copyright Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, which was produced in 1911. (July 2016) |

Quartz-porphyry, in layman's terms, is a type of volcanic (igneous) rock containing large porphyritic crystals of quartz.[1][2] These rocks are classified as hemi-crystalline acid rocks.

Structure

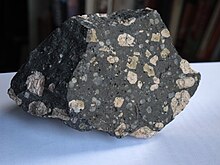

editThe quartz crystals exist in a fine-grained matrix, usually of micro-crystalline or felsitic structure. In specimens, the quartz appears as small rounded, clear, greyish, vitreous blebs, which are crystals, double hexagonal pyramids, with their edges and corners rounded by resorption or corrosion. Under the microscope they are often seen to contain rounded enclosures of the ground-mass or fluid cavities, which are frequently negative crystals with regular outlines resembling those of perfect quartz crystals. Many of the latter contain liquid carbonic acid and a bubble of gas that may exhibit vibratile motion under high magnifying powers.[3]

Variants

editIn addition to quartz there are usually phenocrysts of feldspar, mostly orthoclase, though a varying amount of plagioclase is often present. The feldspars are usually full and cloudy from the formation of secondary kaolin and muscovite throughout their substance. Their crystals are larger than those of quartz and sometimes attain a length of two inches. Not uncommonly scales of biotite are visible in the specimens, being hexagonal plates, which may be weathered into a mixture of chlorite and epidote.[3]

Common minerals

editApatite, magnetite, and zircon, all in small but frequently perfect crystals, are almost universal minerals of the quartz-porphyries. The ground-mass is finely crystalline and to the unaided eye has usually a dull aspect resembling common earthenware; it is grey, green, reddish or white. Often it is streaked or banded by flow during cooling, but as a rule these rocks are not vesicular.[3]

Two main types may be recognized by means of the microscope; the felsitic and the microcrystalline. In the former the ingredients are so fine-grained that in the thinnest slices they cannot be determined by means of the microscope. Some of these rocks show perlitic or spherulitic structure, and such rocks were probably originally glassy (obsidians or pitchstones), but by lapse of time and processes of alteration have slowly passed into very finely crystal-line state. This change is called devitrification; it is common in glasses, as these are essentially unstable. A large number of the finer quartz-porphyries are also in some degree silicified of impregnated by quartz, chalcedony and opal, derived from the silica set free by decomposition (kaolinization) of the original feldspar. This re-deposited silica forms veins and patches of indefinite shape or may bodily replace a considerable area of the rock by metasomatic substitution. The opal is amorphous, the chalcedony finely crystalline and often arranged in spherulitic growths that yield an excellent black cross in polarized light. The microcrystalline ground-masses are those that can be resolved into their component minerals in thin slices by use of the microscope. They prove to consist essentially of quartz and feldspars, which are often in grains of quite irregular shape (microgranitic).[3]

In other cases these two minerals are in graphic intergrowth, often forming radiate growths of spherulites consisting of fibers of extreme tenuity; this type is known as granophyric. There is another group in which the matrix contains small rounded or shapeless patches of quartz in which many rectangular feldspars are embedded; this structure is called micropoikilitic, and though often primary is sometimes developed by secondary changes that involve the deposit of new quartz in the ground-mass. As a whole those quartz-porphyries that have microcrystalline ground-masses are rocks of intrusive origin. Elvan is a name given locally to the quartz-porphyries that occur as dikes in Cornwall. In many of them the matrix contains scales of colorless muscovite or minute needles of blue tourmaline. Fluorite and kaolin appear also in these rocks, and the whole of these minerals are due to pneumatolytic action by vapors permeating the porphyry after it had consolidated but probably before it had entirely cooled. Many ancient rhyolitic quartz-porphyries show on their weathered surfaces numerous globular projections. They may be several inches in diameter, and vary from this size down to a minute fraction of an inch. When struck with a hammer they may detach readily from the matrix as if their margins were defined by a fissure. If they are broken across their inner portions are often seen to be filled with secondary quartz, chalcedony or agate: some of them have a central cavity, often with deposits of quartz crystals; they also frequently exhibit a succession of rounded cracks or dark lines occupied by secondary products. Rocks having these structures are common in north Wales and Cumberland; they occur also in Jersey, the Vosges and Hungary. It has been proposed to call them pyromerides.[3]

Much discussion has taken place regarding the origin of these spheroids, but it is generally admitted that most of them were originally spherulites, and that they have suffered extensive changes through decomposition and silicification. Many of the older quartz-porphyries that occur in Paleozoic and Pre-Cambrian rocks have been affected by earth movements, and have experienced crushing and shearing. In this way they become schistose, and from their feldspar minute plates of sericitic white mica are developed, giving the rock in some cases very much of the appearance of mica-schists. If there have been no phenocrysts in the original rock, very perfect mica-schists may be produced, which can hardly be distinguished from sedimentary schists, though chemically somewhat different on account of the larger amounts of alkalis igneous rocks contain. When phenocrysts were present they often remain, though rounded and dragged apart while the matrix flows around them. The glassy or felsitic enclosures in the quartz are then very suggestive of an igneous origin for the rock. Such porphyry-schists have been called porphyroids or porphyroid-schists, and in the United States the name aporhyolite has been used for them. They are well known in some parts of the Alps, Westphalia, Charnwood (England), and Pennsylvania. The halleflintas of Sweden are also in part acid igneous rocks with a well-banded schistose or granulitic texture. The quartz-porphyries are distinguished from the rhyolites by being either intrusive rocks or Palaeozoic lavas. All Tertiary acid lavas are included under rhyolites. The intrusive quartz-porphyries are equally well described as granite-porphyries.[3]

References

edit- ^ University of Salzburg, quartz-porphyry

- ^ Geology of the Island of Arran, Quartz Porphyry

- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Flett, John Smith (1911). "Quartz-Porphyry". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 717–718.