Rav Ashi (Hebrew: רב אשי) ("Rabbi Ashi") (352–427) was a Babylonian Jewish rabbi, of the sixth generation of amoraim. He reestablished the Academy at Sura and was the first editor of the Babylonian Talmud.

The original pronunciation of his name may have been Asheh, as suggested by the rhyming of his name with "Mosheh" in Maimonides' writings,[1] and a possible rhyme with the word mikdashei (Psalms 73:17) in the Talmud itself.[2]

Biography

editAccording to a tradition preserved in the academies, Rav Ashi was born in the same year that Rava (the great teacher of Mahuza) died,[3] and he was the first important teacher in the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia after Rava's death. Simai, Ashi's father, was a rich and learned man, a student of the college of Naresh near Sura, which was directed by Rav Pappa, Rava's disciple. Ashi's teacher was Rav Kahana III, a member of the same college, who later became president of the academy at Pumbedita. Ashi married the daughter of Rami bar Hama,[4] or Rami b. Abba according to other texts.[5]

Ashi was rich and influential, owning many properties and forests.[6] The Talmud gives him as an example of "Torah and greatness combined in one place", that is to say, he possessed both scholarly accomplishment and political authority,[7] and he had authority even over the exilarch Huna bar Nathan.[7]

Elevation of Sura

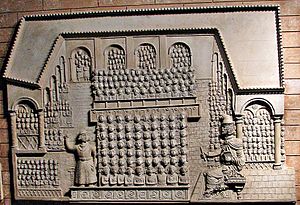

editWhile still young, Rav Ashi became the head of the Sura Academy, his great learning being acknowledged by the older teachers. It had been closed since Rav Chisda's death (309), but under Rav Ashi it once again became the intellectual center of the Babylonian Jews. Ashi contributed to its material grandeur also, rebuilding the academy and the synagogue connected with it in Mata Mehasya,[8] sparing no expense and personally superintending their reconstruction.[9] As a direct result of Rav Ashi's renown, the Exilarch came annually to Sura in the month after Rosh Hashana to receive the respects of the assembled representatives of the Babylonian academies and congregations. These festivities and other conventions in Sura were so splendid that Rav Ashi expressed his surprise that some of the Gentile residents of Sura were not tempted to accept Judaism.[10][11]

Sura maintained the prominence conferred on it by Rav Ashi for several centuries, and only during the last two centuries of the Gaonic period did Pumbedita again become its rival. Rav Ashi's son Tabyomi (known as Mar bar Rav Ashi) was a recognized scholar, but only in 455, 28 years after his father's death, did he receive the position that his father had so successfully filled for more than half a century.

Compilation of the Gemara

editHis commanding personality, his scholarly standing, and wealth are sufficiently indicated by the saying, then current, that since the days of Rabbi Judah haNasi, learning and social distinction were never so united in one person as in Rav Ashi.[7] Indeed, just as Judah haNasi compiled and edited the Mishnah; Rav Ashi made it the labor of his life to collect and edit under the name of Gemara, the explanations of the Mishnah which had been taught in the Babylonian academies since the days of Rav, together with all the discussions connected with them, and all the halakhic and aggadic material covered in the schools.[11]

Together with his disciples and the scholars who gathered in Sura for the "Kallah", or semi-annual college conference, he completed this task. The kindly attitude of King Yazdegerd I, as well as the devoted and respectful recognition of his authority by the academies of Nehardea and Pumbedita, greatly favored the undertaking. A particularly important element in Ashi's success was the length of his tenure of office as head of Sura Academy. According to a tradition brought by Hai Gaon, he held the position for 60 years, though given his approximately 75-year lifespan it is possible this number was rounded upwards. According to the same tradition, these 60 years were so symmetrically apportioned that each tractate required six months (including a single Kallah) for the study of its Mishnah and the redaction of the traditional expositions of the same (Gemara), totaling 30 years for the 60 tractates. The same process was repeated in the next 30 years. Indeed, the Talmud itself mentions an earlier and a later version of Rav Ashi's teachings on at least one subject.[12]

Beyond this, the Talmud itself contains not the slightest intimation of the activity which Ashi and his school exercised in this field for more than half a century. Even whether this editorial work was written down, and thus, whether the putting of the Babylonian Talmud into writing took place under Rav Ashi or not, cannot be answered from any statement in the Talmud. It is nevertheless probable that the fixation of the text of so comprehensive a literary work could not have been accomplished without the aid of writing.[11]

The work begun by Rav Ashi was continued in the two succeeding generations and completed by Ravina II, another president of the college at Sura, who died in 499. To the work as Ravina left it, only slight additions were made by the Saboraim. To one of these additions—that to an ancient utterance concerning the "Book of Adam, the First Man,"—this statement is appended: "Rav Ashi and Ravina are the last representatives of independent decision (hora'ah)",[2] an evident reference to the work of these two in editing the Babylonian Talmud, which as an object of study and a fountainhead of practical "decision" was to have the same importance for the coming generations as the Mishnah had had for the Amoraim.[11]

Teachings

edit- A talmid chacham who is not as strong as iron is not a talmid chacham.[13]

- Whoever is arrogant is blemished.[14]

Tomb of Rav Ashi

editAccording to traditional Jewish belief, the tomb of Rav Ashi is situated on a hill overlooking Kibbutz Manara, Israel. Muslims claim that it is the tomb of a Shi'ite Muslim, Sheikh Abbad, considered a founder of the Shi'ite movement in Lebanon who lived around 500 years ago. When Israel withdrew from South Lebanon in May 2000, the main obstacle holding up the deployment of United Nations peacekeepers along the border was the allocation of this disputed site. It was among the last to be settled between the State of Israel and Lebanon. One option was to erect a barricade around the tomb to prevent Muslims and Jews from visiting the site. Subsequent to the Blue Line drawn by the United Nations, the border fence cuts through the middle of the disputed tomb.[15]

See also

edit- Mar bar Rav Ashi, his son, the seventh generation Amora sage of Babylon

References

edit- ^ In Iggeret Teiman

- ^ a b Bava Metzia 86a

- ^ Kiddushin 72b

- ^ Beitzah 29b; however, according to Aharon Heimann (Toldot Tanaaim veAmoraim) this is a misprint.

- ^ Hullin 111a

- ^ Moed Kattan 12b; Nedarim 62b

- ^ a b c Gittin 59a; Sanhedrin 36a

- ^ Sherira Gaon (1988). The Iggeres of Rav Sherira Gaon. Translated by Nosson Dovid Rabinowich. Jerusalem: Rabbi Jacob Joseph School Press - Ahavath Torah Institute Moznaim. p. 110 (chapter 11). OCLC 923562173.

In all those years after R. Pappa, R. Ashi was gaon in Sura. He came to Mata Mehasya, tore down the Synagogue of Bei Rav, and rebuilt it (as we say in [Chapter] HaShutafin), making a number of fine improvements. He convened [in Mata Mehasya] festivals and fast days that [until then] had been the prerogative only of the exilarch and in Nehardea.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 11a; Baba Bathra 3b)

- ^ Berachot 17b

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jastrow, Marcus; Bacher, Wilhelm (1901–1906). "Ashi". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Bava Batra 157b

- ^ Taanit 4a

- ^ Megillah 29a

- ^ קבר הרב יחולק: חציו בישראל, חציו בלבנון

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jastrow, Marcus; Bacher, Wilhelm (1901–1906). "Ashi". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. It has the following bibliography:

- Letter of Sherira Gaon;

- Heilprin, Seder ha-Dorot;

- Zacuto, YuḦasin;

- Weiss, Dor, iii. 208 et seq.;

- W. Bacher, Agada der Babyl. Amoräer, p. 144.