"Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" (sometimes referred to erroneously as "Everybody Must Get Stoned")[1] is a song written and recorded by the American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan. Columbia Records first released an edited version as a single in March 1966, which reached numbers two and seven in the US and UK charts respectively. A longer version appears as the opening track of Dylan's seventh studio album, Blonde on Blonde (1966), and has been included on several compilation albums.

| "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

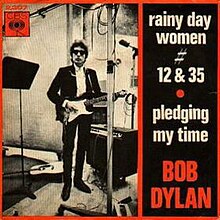

Dutch picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by Bob Dylan | ||||

| from the album Blonde on Blonde | ||||

| B-side | "Pledging My Time" | |||

| Released | March 22, 1966 | |||

| Recorded | March 10, 1966 | |||

| Studio | Columbia, Nashville | |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Bob Dylan | |||

| Producer(s) | Bob Johnston | |||

| Bob Dylan singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" was recorded in one take in Columbia's Nashville, Tennessee studio with session musicians. The track was produced by Bob Johnston and features a raucous brass band accompaniment. There has been much debate over both the meaning of the title and of the recurrent chorus, "Everybody must get stoned". Consequently, it became controversial, with some commentators labeling it as "a drug song". The song received acclaim from music critics, several of whom highlighted the playful nature of the track. Over the years, it became one of Dylan's most performed concert pieces, sometimes with variations in the arrangement.

Background and recording

editA few weeks after the release of his sixth studio album Highway 61 Revisited (1965), Bob Dylan began to record his next album on October 5, 1965, at Columbia Studio A, New York City. The producer was Bob Johnston who had supervised all the later recording sessions for Highway 61 Revisited in the same studio.[2][3] Following unproductive sessions in November 1965 and January 1966, Johnston suggested that Dylan move the location for his next recording session to Nashville, Tennessee.[2] Johnston hired experienced session musicians, including Charlie McCoy, Wayne Moss, Kenneth Buttrey and Joe South, to play with Dylan.[2] They were joined by Robbie Robertson and Al Kooper who had both played at earlier sessions.[2]

Paul Williams described "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" as "a sound, a set of sounds, created on the spot, shaped by the moment just as Dylan's songwriting method is reshaped at each separate moment in his career."[4] The song is notable for its brass band arrangement and the controversial chorus "Everybody must get stoned". Kooper, who played keyboards on Blonde on Blonde, recalled that when Dylan initially demoed the song to the backing musicians in Columbia's Nashville studio, Johnston suggested that "it would sound great Salvation Army style".[5] When Dylan queried how they would find horn players in the middle of the night, McCoy, who played trumpet, made a phone call and summoned a trombone player.[5]

The track was recorded in Columbia Music Row Studios in Nashville in the early hours of March 10, 1966.[7] In the account by Dylan biographer Howard Sounes, the chaotic musical atmosphere of the track was attained by the musicians playing in unorthodox ways and on unfamiliar instruments. McCoy switched from bass to trumpet. Drummer Kenny Buttrey set up his bass drum on two chairs and played it using a timpani mallet. Moss played bass, while Strzelecki played Kooper's organ. Kooper played a tambourine.[8] Producer Bob Johnston recalled, "all of us walking around, yelling, playing and singing."[9] Following one rehearsal, the song was recorded in a single take.[10] Guitarist Robertson missed the recording as he had left the studio to buy cigarettes.[10]

Sean Wilentz, who listened to the complete studio tapes to research his book on Dylan, wrote that the chatter before the take is "if not seriously whacked, certainly jacked up and high-spirited." Before the take, producer Bob Johnston asked Dylan for the song's title and Dylan replied, "A Long-Haired Mule and a Porcupine Here." Johnston said, "It's the only one time that I ever heard Dylan really laugh, really belly-laugh ... going around the studio, marching in that thing."[9]

Sounes quoted Moss recalling that in order to record "Rainy Day Women", Dylan insisted the backing musicians must be intoxicated. A studio employee was sent to an Irish bar to obtain "Leprechaun cocktails". In Sounes's account, Moss, Hargus "Pig" Robbins, and Henry Strzelecki claimed they also smoked a "huge amount" of marijuana and "got pretty wiped out". Sounes stated that some musicians, including McCoy, remained unintoxicated.[8] This version of events has been challenged by Wilentz's and Sanders's studies of the making of Blonde on Blonde. According to Wilentz, both McCoy and Kooper insisted that all the musicians were sober and that Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman, would not have permitted pot or drink in the studio. In support of this account, Wilentz pointed out that three other tracks were recorded that night in the Nashville studio, all of which appeared on the final album.[7][9] McCoy recalled the "Leprechaun cocktails" incident as relating to a different recording session several years later.[11]

Composition and lyrical interpretation

editDylan biographer Robert Shelton writes that he was told by Phil Spector that the inspiration for the song came when Spector and Dylan heard Ray Charles on a Los Angeles jukebox sing "Let's Go Get Stoned", written by husband and wife songwriting team Ashford & Simpson. Spector said "they were surprised to hear a song that free, that explicit", referring to its chorus of "getting stoned" as an invitation to indulge in alcohol or narcotics.[12] In fact, the Charles song was released in April 1966, after "Rainy Day Women" was recorded.[13] Both the Coasters and Ronnie Milsap released versions in 1965; the Coasters version was a B-side and commercially unsuccessful, and journalist Daryl Sanders suggested that it may have been Milsap's version, the B-side of "Never Had It So Good", which Dylan heard.[14]

The song is recorded as a twelve-bar blues, although the lyrics are not typical of the blues genre.[15] However, the pattern of a repeated introduction (i.e. "They'll stone ya when they say that it’s the end...") and conclusion "I would not feel so all alone / Everybody must get stoned") to each stanza recalls a blues format.[15] Musicologist Wilfrid Mellers described the song as "musically corny: a parody of a New Orleans marching or Yankee Revivalist band".[16] According to music scholar Timothy Koozin, Dylan "exaggerates the musical vulgarity with a descending chromatic figure" that is out of place in a twelve-bar blues, and serves to "form a mimetic representation of sinking into a 'stoned' stupor".[17]

After recording Blonde on Blonde, Dylan embarked on his 1966 world tour. At a press conference in Stockholm on April 28, 1966, Dylan was asked about the meaning of his new hit single, "Rainy Day Women". Dylan replied the song was about "cripples and orientals and the world in which they live ... It's a sort of Mexican thing, very protest ... and one of the protestiest of all things I've protested against in my protest years."[18]

Shelton states that, as the song rose up the charts, it became controversial as a "drug song"; consequently the song was banned by some American and British radio stations. He mentions that Time magazine, on July 1, 1966, wrote: "In the shifting multi-level jargon of teenagers, 'to get stoned' does not mean to get drunk but to get high on drugs ... a 'rainy-day woman', as any junkie [sic] knows, is a marijuana cigarette."[12][19] Dylan responded to the controversy by announcing, during his May 27, 1966, performance at the Royal Albert Hall, London, "I never have and never will write a drug song."[20]

According to Dylan critic Clinton Heylin, Dylan was determined to use a "fairly lame pun"—the idea of being physically stoned for committing a sin, as opposed to being stoned on "powerful medicine"—to avoid being banned on the radio. Given its Old Testament connotations, Heylin argued that the Salvation Army band backing becomes more appropriate. Heylin further suggested that the song's title is a Biblical reference, taken from the Book of Proverbs, "which contains a huge number of edicts for which one could genuinely get stoned". He suggested that the title "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" refers to Proverbs chapter 27, verse 15 (in the King James Bible): "A continual dropping in a very rainy day and a contentious woman are alike."[5] Alternately, writer and musician Mike Edison, who called the song "Bob Dylan's stoner anthem", noted of the song's title that, "Twelve multiplied by 35 is 420, but I'm sure this is just good stoner kismet and not some sort of psychotronic Rosetta stone"—referring to the use of 420 as a slang term in cannabis culture, which the song's release predates.[21]

Dylan critic Andrew Muir suggested that the mood of paranoia conjured up by the recurrent phrase "they'll stone you" is a reference to the hostile reaction of Dylan's audience to his new sound. "Dylan was 'being stoned' by audiences around the world for moving to Rock from Folk," wrote Muir, who also suggested the seemingly nonsensical verses of "Rainy Day Women" can be heard as echoes of social and political conflicts in the U.S. For Muir, "They'll stone ya when you're tryin’ to keep your seat" evokes the refusal of black people to move to the back of the bus during the civil rights struggle. For Muir, "They'll stone you and then say you are brave / They'll stone you when you are set down in your grave" reminds listeners that Dylan also wrote "Masters of War" and other "anti-militarism songs that mourned the waste of young men being sent off to be maimed or killed".[22] Koozin interprets the song as aimed at the media and "every other authoritative force in society that oppresses and clouds the individual's mind with untruths".[23] He comments that there is a disconnect between the jovial atmosphere of the track and the "seriousness of the subject matter".[23] David Yaffe felt that it was "the equation between toking up and a public stoning that made it Dylanesque".[24]

According to Heylin, Dylan "finally explained" the song when speaking to New York radio host Bob Fass in 1986: "'Everybody must get stoned' is like when you go against the tide ... you might in different times find yourself in an unfortunate situation and so to do what you believe in sometimes ... some people they just take offence to that. You can look through history and find that people have taken offence to people who come out with a different viewpoint on things."[25]

In a 2012 interview in Rolling Stone, Mikal Gilmore asked Dylan if he worried about "misguided" interpretations of his songs, adding: "For example, some people still see 'Rainy Day Women' as coded about getting high." Dylan responded: "It doesn't surprise me that some people would see it that way. But these are people that aren't familiar with the Book of Acts."[26]

Releases

editAn edited version of "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35", lasting 2 minutes and 26 seconds, was released as a single on March 22, 1966, with "Pledging My Time" as the B-side.[27] The third and fifth verses were omitted, to make the duration more suitable for radio play.[27] The single entered the Billboard Hot 100 charts on April 23 and remained on the chart for nine weeks, peaking at number two.[27] On May 12, the single entered the UK Singles Chart for the start of an eight-week run, where its highest placing was seventh.[27] It also appeared at number three in Canada,[28] and ninth in the Netherlands.[29] Blonde on Blonde, Dylan's seventh studio album, was issued as a double album on June 20, with "Rainy Day Women" and "Pledging My Time" as its first two tracks.[30][31] The album track has a duration of 4 minutes and 36 seconds.[32][33]

The song has been included on several of Dylan's compilation and live albums.[34] A short rehearsal, lasting around 1:41, was included with the finished track on the collector's edition of The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966 (2015); this has a total duration of 6:17.[7][35]

Critical comments

editCash Box described the single version as a "rollicking, honky-tonk-ish blueser essayed in a contagious good-natured style by the songster."[36] Record World said that the "happytime sound with bitter lyric sounds as if it were recorded at a fun party."[37] Sandy Gardiner of The Ottawa Journal wrote that the song was "good for a laugh ... crazy title and the song is even cornier" and felt that it could be commercially successful despite being "nonsense".[38]

Reviewing the album version, Ralph Gleason of the San Francisco Examiner welcomed the song as "comic, satirical ... with its Ma Rainey traditional blues feeling, its wild lyrics."[39] London Life reviewer Deirdre Leigh enjoyed the song as "jolly, uncomplicated and so blatantly meaningless",[40] In Crawdaddy!, Williams opined that the song was "brilliant in its simplicity: in a way, it's Dylan's answer to the uptight cats who are searching for messages."[41] Craig McGregor of The Sydney Morning Herald felt that, like some other tracks from the album, the song was forgettable, and wrote that "stripped of its drug implications, [the song] is a banal piece of musical hokum".[42]

In his 1990 book Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, Williams wrote that the "combination drunk party/revival meeting sound of the song is wonderful", and resulted from the "unique musical chemistry" between Dylan, the musicians and the producer.[4] Mike Marqusee enjoyed the track as a "marvelous one-off, even in Dylan's catalogue".[43] Similarly, John Nogowski regarded it as "a delightful stroke of lunacy ... refreshing".[30] Neil Spencer gave the song a rating of 4/5 stars in an Uncut magazine Dylan supplement in 2015.[44]

In 2013, readers of Rolling Stone voted "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" the third-worst of Dylan's songs. The magazine's Andy Green wrote that "today many fans feel it's the only weak moment on the otherwise flawless Blonde on Blonde".[45] The same year, Jim Beviglia included the song in his ranking of Dylan's "finest"; suggesting that attempting to analyse the meaning behind the track in depth was pointless, and that "the song just wants listeners to enjoy themselves for the duration of it".[46] In 2015, the song was ranked 72nd on Rolling Stone's "100 Greatest Bob Dylan Songs".[47]

Live performances and cover versions

editAccording to his official website, Dylan has performed "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" live 963 times, more than any other track on Blonde on Blonde.[34][48] It is the eleventh-most performed number from over 700 different songs that he has played live.[48] The first performance was at the Isle of Wight Festival on August 31, 1969, and the most recent was at Desert Trip in Indio, California on October 14, 2016.[49] A day before the Indio show, in Las Vegas, it became the first song he performed in concert after the announcement that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[50] During Dylan's 1978 world tour, the song was performed as an instrumental, and in the early 2000s it was performed in what Oliver Trager described as a "roadhouse blues" style.[51] Yaffe believed that while Dylan deliberately sounded "stoned" in the original studio recording, his live performances several decades later were performed in a voice "more like a grizzled bluesman than a druggie".[24]

The first cover version of "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" was recorded soon after the original by Blonde on Blonde producer Johnston, using the pseudonym Colonel Jubilation B. Johnson, and several musicians from the Dylan recording session. According to Mark Deming, Johnston "became so enamored of the shambolic sound of 'Rainy Day Women' that he and the Nashville session crew who played on Blonde on Blonde used it as the basis for an entire album". The album including the song, Moldy Goldies: Colonel Jubilation B. Johnston and His Mystic Knights Band and Street Singers, was released in 1966 by Columbia records.[52][33]

Personnel

editMusicians[53]

- Bob Dylan – vocals, harmonica

- Charlie McCoy – trumpet

- Wayne Moss – electric bass

- Henry Strzelecki – organ

- Hargus "Pig" Robbins – piano

- Al Kooper – tambourine

- Kenneth Buttrey – drums

- Wayne Butler – trombone

Technical[53]

- Bob Johnston – record producer

Charts performance

editThe song reached number two on the Billboard Hot 100 in the week of May 21, 1966. The Mamas and the Papas' "Monday, Monday" prevented it from reaching the top of the chart.[54] "Like a Rolling Stone" (1965) had also reached number two; they were Dylan's highest-charting singles until "Murder Most Foul" in 2020.[55]

Weekly singles charts

edit

|

Year-end chartsedit

|

Notes

edit- ^ From Australian Chart Book 1940–1969 compiled by David Kent, "based on charts specially compiled for this publication, from hit parades, radio charts and best sellers lists".[57]

- ^ Based on chart positions, not sales, for the year to December 10, 1966[61]

- ^ Based on "a weighted point system" which took account of both time and highest position on weekly charts, for the year to November 15, 1966.[62]

References

edit- ^ Trager 2004, p. 508

- ^ a b c d Wilentz 2010

- ^ Björner, Olof. "1965 Concerts, Interviews and Recording Sessions". Still on the Road. Archived from the original on August 22, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Williams 2004, pp. 192–193

- ^ a b c Heylin 2009, pp. 377–379

- ^ Sanders 2020, p. 224.

- ^ a b c Björner, Olof (November 8, 2013). "1966 Blonde On Blonde recording sessions and world tour". Still on the Road. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Sounes 2001, pp. 203–204

- ^ a b c Wilentz 2009, p. 123

- ^ a b Sanders 2020, p. 232

- ^ Sanders 2020, p. 226

- ^ a b Shelton 2011, pp. 224–225

- ^ Whitburn 2010, p. 122

- ^ Sanders 2020, pp. 229–230

- ^ a b Starr 2021, 1523–1536

- ^ Mellers 1985, p. 144

- ^ Koozin 2016, pp. 85–86

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 209

- ^ "Going to Pot". Time. Vol. 88, no. 1. July 1, 1966. pp. 56–57.

- ^ "Dylan View on the Big Boo", Melody Maker, June 4, 1966

- ^ Edison, Mike (2008). I Have Fun Everywhere I Go: Savage Tales of Pot, Porn, Punk Rock, Pro Wrestling, Talking Apes, Evil Bosses, Dirty Blues, American Heroes, and the Most Notorious Magazines in the World. Faber & Faber. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-86547-964-7.

- ^ Muir, Andrew (January 10, 2013). "Everybody Must Get Stoned" (PDF). a-muir.co.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Koozin 2016, p. 86

- ^ a b Yaffe 2011, p. 11

- ^ Heylin 2021, p. 394

- ^ Gilmore, Michael (September 27, 2012). "Bob Dylan Unleashed". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Sanders 2020, p. 251

- ^ a b "RPM 100: week of May 23rd, 1966". RPM. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2022 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ a b "Bob Dylan: Rainy Day Women #12 & 35". Dutch Charts. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Nogowski 2022, p. 59

- ^ Heylin 2016, 7290: a Sony database of album release dates ... confirms once and for all that it came out on June 20, 1966".

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen. "Blonde on Blonde review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Marcus 2005, p. 250

- ^ a b "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35". Bob Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen. "The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966 review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. April 2, 1966. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Singles Reviews" (PDF). Record World. April 2, 1966. p. 6. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Gardiner, Sandy (April 23, 1966). "Platter patter ... and idle chatter". The Ottawa Journal. p. 54.

- ^ Gleason, Ralph (July 31, 1966). "Dylan's 'Blonde' broke all the rules". San Francisco Examiner. p. TW.31. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Leigh, Deirdre. "Records". London Life. p. 46.

- ^ Williams 1969, p. 68

- ^ McGregor, Craig (October 8, 1966). "Pop scene". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 19.

- ^ Marqusee 2005, p. 199

- ^ Spencer, Neil (2015). "Blonde on Blonde". Uncut: Bob Dylan. pp. 24–25.

- ^ Greene, Andy (July 3, 2013). "Readers' Poll: The 10 Worst Bob Dylan Songs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ Beviglia 2013, pp. 9–10

- ^ "100 Greatest Bob Dylan Songs". Rolling Stone. May 24, 2020 [2015]. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Songs played live". Bob Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35". Bob Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Mikael (October 14, 2016). "A genius in Sin City: Bob Dylan celebrates his Nobel Prize – well, sort of – with an exuberant Vegas gig". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ Trager 2004, p. 509

- ^ Deming, Mark. "Moldy Goldies: Colonel Jubilation B. Johnston and His Mystic Knights Band and Street Si review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Sanders 2020, p. 276

- ^ "Hot 100". Billboard. May 21, 1966. p. 24.

- ^ Pavia, Will (April 10, 2020). "Memories of JFK give Dylan his first chart topper at 78". The Times. p. 29.

- ^ Kent 2005, p. 61

- ^ "Australian Chart Book 1940–1969". Australian Chart Book. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "Official singles charts results matching Rainy Day Women Nos 12 and 35". Official Charts. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "Chart history: Bob Dylan". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Downey, Pat; Albert, George; Hoffman, Frank (1994). Cash Box pop singles charts, 1950–1993. Englewood: Libraries Unlimited. p. 105. ISBN 9781563083167.

- ^ a b "Top Records of 1966". Billboard. December 24, 1966. p. 34.

- ^ a b "Top 100 chart hits of 1966". Cash Box. December 24, 1966. pp. 29–30.

Bibliography

edit- Beviglia, Jim (2013). Counting Down Bob Dylan: His 100 Finest Songs. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8824-1.

- Heylin, Clinton (2009). Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Volume One: 1957–73. Constable. ISBN 978-1-84901-051-1.

- Heylin, Clinton (2016). Judas!: From Forest Hills to the Free Trade Hall: A Historical View of Dylan's Big Boo (Kindle ed.). Route Publishing. ISBN 978-1-901927-68-9.

- Heylin, Clinton (2021). The Double Life of Bob Dylan. Vol. 1 1941-1966, A restless, hungry feeling. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-588-6.

- Kent, David (2005). Australian Chart Book 1940-1969. Turramurra: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-44439-5.

- Koozin, Timothy (2016). "Irony, Myth, and Temporal Organization in the Early Songs of Bob Dylan". In Turner, Katherine L. (ed.). This is the Sound of Irony: Music, Politics and Popular Culture. London: Routledge. pp. 73–89. ISBN 9781317010531.

- Marcus, Greil (2005). Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads. London: Faber and Faber. p. 250. ISBN 9780571223855.

- Marqusee, Mike (2005). Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s. New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-686-5.

- Mellers, Wilfrid (1985). A Darker Shade of Pale: A Backdrop to Bob Dylan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-571-13345-2.

- Nogowski, John (2022). Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography, 1961-2022 (3rd ed.). Jefferson: McFarland and Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-4362-5.

- Sanders, Daryl (2020). That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound: Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde (epub ed.). Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61373-550-3.

- Shelton, Robert (2011). No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan (Revised & updated ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-184938-458-2.

- Sounes, Howard (2001). Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-1686-8.

- Starr, Larry (2021). Listening to Bob Dylan. Music in American Life (Kindle ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-05288-0.

- Trager, Oliver (2004). Keys to the Rain: the Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-8230-7974-2.

- Whitburn, Joel (2010). Hot R&B Songs: 1942-2010. Menomonee Falls: Record Research. ISBN 978-0-89820-186-4.

- Wilentz, Sean (2009). Bob Dylan in America. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-150-5.

- Wilentz, Sean (2010). "4: The Sound of 3:00 am: The Making of Blonde on Blonde, New York City and Nashville, October 5, 1965 – March 10 (?), 1966". Bob Dylan in America. London: Vintage Digital. ISBN 978-1-4070-7411-5. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2022 – via Pop Matters.

- Williams, Paul (1969) [1st pub. Crawdaddy!: July 1966]. "Understanding Dylan". Outlaw blues; a book of rock music. New York: E. P. Dutton. pp. 59–69.

- Williams, Paul (2004) [1990]. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist: The Early Years, 1960–1973. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-095-0.

- Yaffe, David (2011). Like a Complete Unknown. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12457-6.

External links

edit- Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35 / Pledging My Time at Discogs (list of releases)

- Bob Dylan - Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 on YouTube

- Lyrics at Bob Dylan's official website