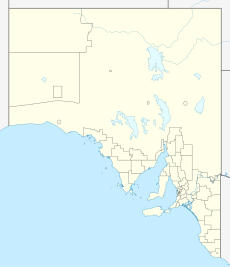

Rapid Bay is a locality that includes a small seaside town and bay on the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia. It lies within the District Council of Yankalilla and its township is approximately 100 km south of the state capital, Adelaide. A pair of jetties are popular attractions for recreational fishing, scuba diving and snorkelling. The bay particularly known as a site for observing leafy seadragons in the wild. Its postcode is 5204.

| Rapid Bay South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Patpangga / Rapid Bay shoreline | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°31′39″S 138°11′22″E / 35.527537°S 138.18951°E[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 16 (2016 census)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5204 | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | ACST (UTC+9:30) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | ACDT (UTC+10:30) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 100 km (62 mi) S of Adelaide | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | District Council of Yankalilla | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Fleurieu and Kangaroo Island[3] | ||||||||||||||

| County | Hindmarsh[1] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Mawson[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Mayo | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Footnotes | Adjoining localities[1] | ||||||||||||||

History

editRapid Bay features in the creation myths of the Kaurna and Ramindjeri peoples most notably as the burial site of the nephew of the Kaurna creator ancestor known as Tjilbruke.[6] There is uncertainty as to the Kaurna name for Rapid Bay, which has been cited as Patparno,[7] Patpangga (meaning "south" or "south place"), and Yarta-kulangga, a popular campsite at Rapid Bay, whose name probably means "place of the separate country". However, there is no evidence that any of these names was a place name for Rapid Bay,[8] though the bay is officially dual-named Patpangga.[9]

Prior to the establishment of the South Australian colony, whalers based on Kangaroo Island were known to have called at Rapid Bay though it was not so named until 1836.[10] South Australia Colonial Surveyor General Colonel William Light made his first landfall on mainland South Australia at Rapid Bay on 8 September 1836.[11] The site was named after Light's ship, the 162 ton brig Rapid. To mark this historic landfall the Colonel's initials, "W.L.", were carved into a large boulder – a replica is visible in the township, while the original is stored in the South Australian Museum, in Adelaide. John Rapid Hoare (7 November 1836 – perhaps 7 July 1916),[12] also named for the brig Rapid, was the first European child born on mainland South Australia. Claims that he was born at Rapid Bay[13] have been refuted.[14]

Rapid Bay was briefly considered by Light as a potential site for the new colony's capital,[15] but with the discovery of the Adelaide Plains it faded into quiet obscurity. On his first visit, Light created a garden then left the bay in the hands of Kangaroo Island sealers and indigenous people from the Encounter Bay area.[16]

Quarrying

editThe BHP constructed the town, an ore-loading jetty and a high voltage power line from Willunga during the period 1938 to 1942 as part of the works undertaken to establish a limestone quarry. During the construction of the jetty, a worker named John Gamlin went missing and was presumed to have fallen from a platform that lacked rails and drowned. The tide was running quickly and wind speeds were reaching 40 miles per hour on the day of his disappearance.[17]

Quarrying commenced in 1942.[18] The limestone was transported by sea and used as a flux at BHP's Whyalla Steelworks in South Australia, and Newcastle and Port Kembla in New South Wales.[15]

In 1948, production averaged 30,000 tonnes per month with a fully mechanised process from electric shovel to crushers, then by conveyor to ship. At that time there were 41 men employed at the project, including office staff.[16]

BHP's assets, including a crushing plant, jetty and loading wharf, were eventually sold to Adelaide Brighton Cement in 1981.

On 1 January 1982, ownership of the jetty was transferred to the Government of South Australia at no cost.[19]

Total production from 1942 to 2013 is estimated at 17 million tonnes, most of which was used for industrial purposes. Incomplete figures indicate production for construction material between 1977 and 2013 was roughly 550,000 tonnes. A small volume of roadbase materials continues to be quarried from the site.[20] The quarry and remaining buildings are located within tenements PM11 and PM12 which as of 2021 are held by Adelaide Brighton Cement and Croser Bros.

The history of the township during the BHP years was recorded by Des Lord in the 2018 book Rapid Bay... Before we forget. History and memoirs of a mining town.[21]

Attractions

editRapid Bay is known for its steep cliffs, caves, beach, two jetties and associated artificial reef. A resident leafy seadragon population inhabits the bay and weedy seadragons are also occasionally seen.

It is considered to be among the best scuba diving sites in South Australia[22] and Australia[23] and has been featured on SportDiver as one of the world's top nine dives.[24] The ecological communities on the jetty piles are well-established and attract large schools of fish including Old Wives and Zebra Fish. Over 70 species of fish have been recorded in Rapid Bay.[25][26] Many marine invertebrates can be observed on the jetty piles and living among the debris on the seafloor. Iconic examples include the Australian giant cuttlefish and the blue-ringed octopus.[citation needed]

Rapid Bay is also a popular recreational fishing site, with fishing possible from shore, boat, kayak and the deck of the public jetty. The historic industrial jetty is permanently closed due to its state of natural decay.[citation needed]

Jetties

editThe first jetty at Rapid Bay was built in the late 1860s, described as "new" in 1867 and assessed by the Marine Board in 1871. It was considered well made but poorly designed owing to its south-westerly heading and the shallowness of water at its terminus. The jetty had been intended to feature a crane to assist with loading and unloading cargoes but the crane was lost in transit from Second Valley in some four-and-a-half fathoms of water where it was abandoned.[27][28] The first jetty at Rapid Bay was constructed of timber and was intended for the export of wool and wheat. Wheat and lead were exported from Second Valley during the 1860s owing to the lack of a suitable road to bring those cargoes to the waterfront at Rapid Bay.[citation needed] The first Rapid Bay jetty's landward end was some 50 yards distant from the later BHP construction.[16]

BHP Jetty

editThe BHP Jetty was originally 490 metres (1,600 ft) long, with a 'T' section of 200 metres (650 ft) length for ship-loading. The jetty terminated in 9.1 metres (30 ft) of water (at lowest tide).[29] Originally built by BHP and later operated by Adelaide Brighton Cement, the jetty ceased commercial operations in 1991.[19] It suffered storm damage in 2004, after which it was progressively closed in stages for the purpose of ensuring public safety. Above the water, the jetty is slowly decaying and is off-limits to the general public. Below the water, the jetty provides habitat for a wide variety of temperate marine species. Since its closure, the above-water structure has also become an increasingly valuable roost for seabirds.[citation needed] The Jetty collapsed in January 2022.[30]

Public Jetty

editConstruction of a new jetty of 240 metres (790 feet) length located 50 metres (160 feet) east of the BHP jetty was completed in 2009 to replace the public amenity lost by the progressive closure of the BHP jetty.[31][32]

The new jetty has since been colonised by marine life and augments the more established ecological communities on and around the historic jetty. At the seaward end, a staircase provides safe and easy entry to the water for divers and snorkelers. The jetty features concrete decking, is artificially lit after dark and is a popular spot for recreational fishing.[citation needed]

Gallery

edit-

Rapid Bay old jetty, viewed from new jetty

-

View of the Town, the Quarry and the Jetty looking west towards Rapid Head (image created in 1950)

-

The limestone quarry at Rapid Bay as seen from the public car park for the jetty.

References

edit- ^ a b c "Search results for 'Rapid Bay, LOCB' with the following datasets being selected – 'Suburbs and Localities', 'Postcode', 'Government Towns', 'Counties', 'Hundreds', 'Local Government Areas', 'SA Government Regions', 'Land Development Plan Zone Categories' and 'Gazetteer'". Location SA Map Viewer. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "State Suburb of Rapid Bay". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Fleurieu Kangaroo Island SA Government region" (PDF). The Government of South Australia. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Mawson (Map). Electoral District Boundaries Commission. 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Climate statistics for PARAWA (SECOND VALLEY FOREST AWS) (nearest station)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ City of Holdfast Bay: Tjilbruke Heritage & the Kaurna People Archived 12 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Arts and culture". City of Marion. 7 February 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Schultz, Chester (4 August 2016). "Place Name Summary (PNS) 1/03: Patpangga" (PDF). Adelaide Research & Scholarship. The Southern Kaurna Place Names Project. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Geographical Names Act 1991 (21)". South Australian Government Gazette. Government of South Australia. 24 March 2011. p. 826.

- ^ "Vol. 15 No. 1 (1 January 1949)". Retrieved 31 July 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ Elder, David F., 'Light, William (1786–1839)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, [1], accessed 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 24, 503. New South Wales, Australia. 19 July 1916. p. 10. Retrieved 29 June 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Firstborn South Australian Male". The Advertiser. Vol. XLIII, no. 13, 310. Adelaide, South Australia. 15 June 1901. p. 11. Retrieved 29 June 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "South Australia's Oldest Natives". The Herald. Vol. X, no. 3012. South Australia. 14 November 1919. p. 4. Retrieved 29 June 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Limestone". Geological Survey of SA. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Walkabout Vol. 15 No. 1 (1 January 1949)". Retrieved 31 July 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ "WORKER DISAPPEARS FROM RAPID BAY JETTY". News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 – 1954). 10 December 1941. p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Cowan, David. "History". Friends of Rapid Bay Jetty. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ a b Friends of Rapid Bay Jetty > History. Accessed 2014-03-21

- ^ "Mineral Deposit Details". minerals.sarig.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "Trove". trove.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Hutchison, Stuart (1 December 2001). "Travellin' South". Australasia Scuba Diver: 18–30.

- ^ Australia 'the best destination for shore diving'

- ^ "9 world's best dives" SportDiver.com. Accessed 2014-03-20.

- ^ Atlas of Living Australia > Rapid Bay Jetty > Fishes. Accessed 2014-03-22

- ^ "Rapid Bay, South Australia". iNaturalist. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "RAPID BAY JETTY". Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 – 1904). 17 August 1867. p. 6. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "RAPID BAY JETTY". Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1869 – 1912). 18 August 1871. p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ The Recorder "B.H.P. at Rapid Bay – Limestone Plant Near Completion" (17 April 1942) Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- ^ Jarvis, Emily (14 January 2022). "History sinks as Fleurieu Peninsula jetty collapses". The Advertiser.

- ^ 'Rapid Bay', [2], retrieved 11/10/2012.

- ^ "'Rapid' progress on new jetty – Local News – News – General – the Times". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

External links

edit- Friends of Rapid Bay Jetty, retrieved 11/10/2012.

- Dive the Rapid Bay Jetty | Diving Adelaide