This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

In computer graphics and digital photography, a raster graphic represents a two-dimensional picture as a rectangular matrix or grid of pixels, viewable via a computer display, paper, or other display medium. A raster image is technically characterized by the width and height of the image in pixels and by the number of bits per pixel.[1] Raster images are stored in image files with varying dissemination, production, generation, and acquisition formats.

The printing and prepress industries know raster graphics as contones (from continuous tones). In contrast, line art is usually implemented as vector graphics in digital systems.[2]

Many raster manipulations map directly onto the mathematical formalisms of linear algebra, where mathematical objects of matrix structure are of central concern.

Etymological

editThe word "raster" has its origins in the Latin rastrum (a rake), which is derived from radere (to scrape). It originates from the raster scan of cathode-ray tube (CRT) video monitors, which draw the image line by line by magnetically or electrostatically steering a focused electron beam.[3] By association, it can also refer to a rectangular grid of pixels. The word rastrum is now used to refer to a device for drawing musical staff lines.

Data model

editThe fundamental strategy underlying the raster data model is the tessellation of a plane, into a two-dimensional array of squares, each called a cell or pixel (from "picture element"). In digital photography, the plane is the visual field as projected onto the image sensor; in computer art, the plane is a virtual canvas; in geographic information systems, the plane is a projection of the Earth's surface. The size of each square pixel, known as the resolution or support, is constant across the grid. Raster or gridded data may be the result of a gridding procedure.

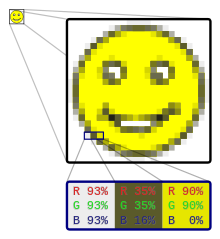

A single numeric value is then stored for each pixel. For most images, this value is a visible color, but other measurements are possible, even numeric codes for qualitative categories. Each raster grid has a specified pixel format, the data type for each number. Common pixel formats are binary, gray-scale, palettized, and full-color, where color depth[4] determines the fidelity of the colors represented, and color space determines the range of color coverage (which is often less than the full range of human color vision). Most modern color raster formats represent color using 24 bits (over 16 million distinct colors), with 8 bits (values 0–255) for each color channel (red, green, and blue). The digital sensors used for remote sensing and astronomy are often able to detect and store wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum; the large CCD bitmapped sensor at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory captures 3.2 gigapixels in a single image (6.4 GB raw), over six color channels which exceed the spectral range of human color vision.

Applications

editImage storage

editMost computer images are stored in raster graphics formats or compressed variations, including GIF, JPEG, and PNG, which are popular on the World Wide Web.[4][5] A raster data structure is based on a (usually rectangular, square-based) tessellation of the 2D plane into cells, each containing a single value. To store the data in a file, the two-dimensional array must be serialized. The most common way to do this is a row-major format, in which the cells along the first (usually top) row are listed left to right, followed immediately by those of the second row, and so on.

In the example at right, the cells of tessellation A are overlaid on the point pattern B resulting in an array C of quadrant counts representing the number of points in each cell. For purposes of visualization a lookup table has been used to color each of the cells in an image D. Here are the numbers as a serial row-major array:

1 3 0 0 1 12 8 0 1 4 3 3 0 2 0 2 1 7 4 1 5 4 2 2 0 3 1 2 2 2 2 3 0 5 1 9 3 3 3 4 5 0 8 0 2 4 3 2 8 4 3 2 2 7 2 3 2 10 1 5 2 1 3 7

To reconstruct the two-dimensional grid, the file must include a header section at the beginning that contains at least the number of columns, and the pixel datatype (especially the number of bits or bytes per value) so the reader knows where each value ends to start reading the next one. Headers may also include the number of rows, georeferencing parameters for geographic data, or other metadata tags, such as those specified in the Exif standard.

Compression

editHigh-resolution raster grids contain a large number of pixels, and thus consume a large amount of memory. This has led to multiple approaches to compressing the data volume into smaller files. The most common strategy is to look for patterns or trends in the pixel values, then store a parameterized form of the pattern instead of the original data. Common raster compression algorithms include run-length encoding (RLE), JPEG, LZ (the basis for PNG and ZIP), Lempel–Ziv–Welch (LZW) (the basis for GIF), and others.

For example, Run length encoding looks for repeated values in the array, and replaces them with the value and the number of times it appears. Thus, the raster above would be represented as:

| values | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | ... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lengths | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ... |

This technique is very efficient when there are large areas of identical values, such as a line drawing, but in a photograph where pixels are usually slightly different from their neighbors, the RLE file would be up to twice the size of the original.

Some compression algorithms, such as RLE and LZW, are lossless, where the original pixel values can be perfectly regenerated from the compressed data. Other algorithms, such as JPEG, are lossy, because the parameterized patterns are only an approximation of the original pixel values, so the latter can only be estimated from the compressed data.

Raster–vector conversion

editVector images (line work) can be rasterized (converted into pixels), and raster images vectorized (raster images converted into vector graphics), by software. In both cases some information is lost, although certain vectorization operations can recreate salient information, as in the case of optical character recognition.

Displays

editEarly mechanical televisions developed in the 1920s employed rasterization principles. Electronic television based on cathode-ray tube displays are raster scanned with horizontal rasters painted left to right, and the raster lines painted top to bottom.

Modern flat-panel displays such as LED monitors still use a raster approach. Each on-screen pixel directly corresponds to a small number of bits in memory.[6] The screen is refreshed simply by scanning through pixels and coloring them according to each set of bits. The refresh procedure, being speed critical, is often implemented by dedicated circuitry, often as a part of a graphics processing unit.

Using this approach, the computer contains an area of memory that holds all the data that are to be displayed. The central processor writes data into this region of memory and the video controller collects them from there. The bits of data stored in this block of memory are related to the eventual pattern of pixels that will be used to construct an image on the display.[7]

An early scanned display with raster computer graphics was invented in the late 1960s by A. Michael Noll at Bell Labs,[8] but its patent application filed February 5, 1970, was abandoned at the Supreme Court in 1977 over the issue of the patentability of computer software.[9]

Printing

editDuring the 1970s and 1980s, pen plotters, using Vector graphics, were common for creating precise drawings, especially on large format paper. However, since then almost all printers create the printed image as a raster grid, including both laser and inkjet printers. When the source information is vector, rendering specifications and software such as PostScript are used to create the raster image.

Three-dimensional rasters

editThree-dimensional voxel raster graphics are employed in video games and are also used in medical imaging such as MRI scanners.[10]

Geographic information systems

editGeographic phenomena are commonly represented in a raster format in GIS. The raster grid is georeferenced, so that each pixel (commonly called a cell in GIS because the "picture" part of "pixel" is not relevant) represents a square region of geographic space.[11] The value of each cell then represents some measurable (qualitative or quantitative) property of that region, typically conceptualized as a field. Examples of fields commonly represented in rasters include: temperature, population density, soil moisture, land cover, surface elevation, etc. Two sampling models are used to derive cell values from the field: in a lattice, the value is measured at the center point of each cell; in a grid, the value is a summary (usually a mean or mode) of the value over the entire cell.

Resolution

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

Raster graphics are resolution dependent, meaning they cannot scale up to an arbitrary resolution without loss of apparent quality. This property contrasts with the capabilities of vector graphics, which easily scale up to the quality of the device rendering them. Raster graphics deal more practically than vector graphics with photographs and photo-realistic images, while vector graphics often serve better for typesetting or for graphic design. Modern computer-monitors typically display about 72 to 130 pixels per inch (PPI), and some modern consumer printers can resolve 2400 dots per inch (DPI) or more; determining the most appropriate image resolution for a given printer-resolution can pose difficulties, since printed output may have a greater level of detail than a viewer can discern on a monitor. Typically, a resolution of 150 to 300 PPI works well for 4-color process (CMYK) printing.

However, for printing technologies that perform color mixing through dithering (halftone) rather than through overprinting (virtually all home/office inkjet and laser printers), printer DPI and image PPI have a very different meaning, and this can be misleading. Because, through the dithering process, the printer builds a single image pixel out of several printer dots to increase color depth, the printer's DPI setting must be set far higher than the desired PPI to ensure sufficient color depth without sacrificing image resolution. Thus, for instance, printing an image at 250 PPI may actually require a printer setting of 1200 DPI.[12]

Raster-based image editors

editRaster-based image editors, such as PaintShop Pro, Corel Painter, Adobe Photoshop, Paint.NET, Microsoft Paint, Krita, and GIMP, revolve around editing pixels, unlike vector-based image editors, such as Xfig, CorelDRAW, Adobe Illustrator, or Inkscape, which revolve around editing lines and shapes (vectors). When an image is rendered in a raster-based image editor, the image is composed of millions of pixels. At its core, a raster image editor works by manipulating each individual pixel.[5] Most[13] pixel-based image editors work using the RGB color model, but some also allow the use of other color models such as the CMYK color model.[14]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Introduction to Computer Graphics, Section 1.1 -- Painting and Drawing". math.hws.edu. Retrieved 2024-08-25.

- ^ "Patent US6469805 – Post raster-image processing controls for digital color image printing". Google.nl. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Bach, Michael; Meigen, Thomas; Strasburger, Hans (1997). "Raster-scan cathode-ray tubes for vision research – limits of resolution in space, time and intensity, and some solutions". Spatial Vision. 10 (4): 403–14. doi:10.1163/156856897X00311. PMID 9176948.

- ^ a b "Types of Bitmaps". Microsoft Docs. Microsoft. 29 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

The number of bits devoted to an individual pixel determines the number of colors that can be assigned to that pixel. For example, if each pixel is represented by 4 bits, then a given pixel can be assigned one of 16 different colors (2^4 = 16).

- ^ a b "Raster vs Vector". Gomez Graphics Vector Conversions. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

Raster images are created with pixel-based programs or captured with a camera or scanner. They are more common in general such as jpg, gif, png, and are widely used on the web.

- ^ "bitmap display". FOLDOC. 2002-05-15. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Murray, Stephen. "Graphic Devices". Computer Sciences, edited by Roger R. Flynn, vol. 2: Software and Hardware, Macmillan Reference USA, 2002, pp. 81–83. Gale eBooks. Accessed 3 Aug. 2020.

- ^ Noll, A. Michael (March 1971). "Scanned-Display Computer Graphics". Communications of the ACM. 14 (3): 143–150. doi:10.1145/362566.362567. S2CID 2210619. Archived from the original on Dec 16, 2023.

- ^ "Patents". Noll.uscannenberg.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ "CHAPTER-1". Cis.rit.edu. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Bolstad, Paul (2008). GIS Fundamentals: A First Text on Geographic Information Systems (3rd ed.). Eider Press. p. 42.

- ^ Fulton, Wayne (April 10, 2010). "Color Printer Resolution". A few scanning tips. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ Tooker, Logan (2022-02-02). "Photoshop vs. CorelDRAW: Which Is Better for Graphic Editors?". MUO. Retrieved 2024-07-13.

- ^ "Print Basics: RGB Versus CMYK". HP Tech Takes. HP. 12 June 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

If people are going to see it on a computer monitor, choose RGB. If you're printing it, use CMYK. (Tip: In Adobe® Photoshop®, you can choose between RGB and CMYK color channels by going to the Image menu and selecting Mode.)