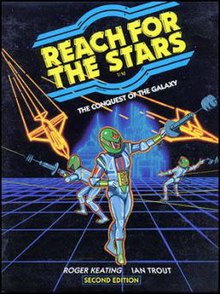

Reach for the Stars is a science fiction strategy video game. It is the earliest known commercially published example of the 4X genre. It was written by Roger Keating and Ian Trout of SSG of Australia and published in 1983 for the Commodore 64 and then the Apple II in 1985. Versions for Mac OS, Amiga, Apple IIGS, and DOS were released in 1988.

| Reach for the Stars | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Strategic Studies Group |

| Publisher(s) | Strategic Studies Group |

| Designer(s) | Roger Keating Ian Trout |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Apple II, Apple IIGS, Commodore 64, DOS, Mac OS, PC-98 |

| Release | 1983: C64, Apple II 1988: Amiga, IIGS, DOS, Mac 1989: PC-98 |

| Genre(s) | Turn-based strategy, 4X |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

The player commands a home star in the galaxy, and then expands to form an interstellar empire by colonizing far-off worlds, building powerful starships, and researching new technologies.

Reach for the Stars was very strongly influenced by the board game Stellar Conquest. Many of RFTS's features have direct correspondence in Stellar Conquest.

Graphics are minimal, yet the tactical and strategic elements provide countless rich combinations for colony development and interstellar warfare. The software's AI also offered a challenging opponent in single-player games. It is not uncommon for a Reach for the Stars game to take over twelve hours to complete in single-player mode and 24 hours with multiple players.

Gameplay

editIn Versions 1 to 3 the player starts off with one planet that has Level 1 technology and a middle level environment. Three types of ships are available:

- Scouts – very inexpensive, incapable of fighting or carrying colonists. These can be used as a low-cost, low-risk means to learn the composition of unknown star systems or the locations and makeup of enemy fleets.

- Transports – incapable of fighting, but can carry colonists.

- Warships – incapable of carrying colonists, but can fight.

Starting players have limited funds, and have to decide where to invest the funds (technology upgrades, ships, or environmental upgrades). Upgrading a world's planetary environment, for example, means that its population grows more quickly, improving production; this is a mixed blessing, however, because if the population grows beyond the maximum allowed for that planet, the costs to feed the population skyrocket. Building a lot of ships early can win a player the game, if the player finds his enemies' home planets before they manage to upgrade their military technology; on the other hand, it can lead to a loss if the player's opponents upgrade first and attack with superior ships.

Each turn is divided into two sections – a development phase, and a movement phase. In the development phase, players work on planetary production, deciding what each planet will produce that turn. In the movement phase, players have the option to send ships to other star systems to explore, colonize, or conquer.

Because the game evolves along so many different axes of possibility, the game offers tremendous replay value. It is quite possible to save a game on the first turn, and have it play out differently each time it is restored.

A bug causes human players that do nothing to become wealthy while computer opponents fight each other. The designers added a feature that causes the computer opponents to attack the human at 20,000 credits.[1]

Reception

editComputer Gaming World in 1983 found Reach for the Stars quite user-friendly and enjoyable, with the single flaw of a lack of notification of natural disasters, which could not fit onto the disk space available. The computer AI and customization of each game were particular highlights of the review.[5] In a 1992 survey of science fiction games the magazine gave the title five of five stars, praising it as "arguably the best science fiction game ever released ... a product still worth playing".[6] A 1994 survey of strategic space games set in the year 2000 and later gave the game four stars out of five, stating that "a worthy update would no doubt raise this game again to 5-star status".[2] Compute! in 1986 called the game "a particularly fine simulation of galactic exploration, combat, and conquest", noting that players needed to balance several different priorities to succeed. It concluded that Reach for the Stars was "one of the better games on the market this year".[7] inCider in 1986 gave the Apple II version three stars ("Above average") out of four, stating that while the game was "exciting", "[i]t's unromantic to say that much of the rest of the game is a matter of juggling numbers, but that's the truth".[4] Jerry Pournelle of BYTE wrote in 1989 that the Mac version of Reach for the Stars was "certainly the best implemented" version of Stellar Conquest.[8] The game was reviewed in 1994 in Dragon #211 by Jay & Dee in the "Eye of the Monitor" column. Jay did not rate the game, but Dee gave the game 3½ out of 5 stars.[3]

The Macworld 1988 Game Hall of Fame named Reach for the Stars runner-up to Trust & Betrayal: The Legacy of Siboot in the Best Role-Playing Game category, calling it a "well-implemented" scenario of economic empire building in outer space.[9]

Norman Banduch reviewed Reach for the Stars in Space Gamer No. 69.[10] Banduch commented that "Reach For The Stars is a most addictive game. After player 10 to 15 hours a week for several months I still find it hard to save the game and go home. It offers a wide variety of set-up conditions and victory conditions, and play is never the same. The computer is a tough foe. Even after the is mastered, there are enough options and random variables to keep it from going stale. I cannot recommend it enough".[10]

Bob Ewald reviewed Reach for the Stars in Space Gamer/Fantasy Gamer No. 77.[11] Ewald commented that "all things considered, I really enjoyed the game. I feel parts of the combat system are illogical, but the game as a whole is great".[11]

In 1996, Computer Gaming World declared Reach for the Stars the 51st-best computer game ever released.[12]

Reviews

edit- Casus Belli #22 (October 1984)[13]

- Jeux & Stratégie HS #3[14]

Sequel

edit| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Computer Gaming World | [15] |

A sequel to Reach for the Stars re-written for the Windows platform was released on September 14, 2000 by developer Strategic Studies Group and publisher Strategic Simulations, Inc. In 2005 Matrix Games, working alongside Strategic Studies Group, updated the 2000 release; this updated version was released in 2005.[16]

Books

editA series of books was written in 2018 by the game company Greentwip, called Interstellar, Anatomy and The Garlan Wars. While its publication is still ongoing, it is being said that a TV channel would produce cinematographic films out of the books. This happened after Greentwip's founder got deep into the story and proposed to give a better and linear approach to all the species that the game aims to deliver to the player, in order to become a better "pure Sci-Fi" experience.[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Wilson, Johnny L.; Brown, Ken; Lombardi, Chris; Weksler, Mike; Coleman, Terry (July 1994). "The Designer's Dilemma: The Eighth Computer Game Developers Conference". Computer Gaming World. pp. 26–31.

- ^ a b Brooks, M. Evan (May 1994). "Never Trust A Gazfluvian Flingschnogger!". Computer Gaming World. pp. 42–58.

- ^ a b Jay & Dee (November 1994). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon (211): 39–42.

- ^ a b Murphy, Brian J. (September 1986). "Game Room". inCider. pp. 113–114. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Curtis, Ed (December 1983). "Reach for the Stars". Computer Gaming World. pp. 27, 49.

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (November 1992). "Strategy & Wargames: The Future (2000–....)". Computer Gaming World. p. 99. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ Trunzo, James V. (February 1986). "Reach for the Stars For Commodore And Apple". Compute!. p. 36. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (January 1989). "To the Stars". BYTE. p. 109.

- ^ Levy, Steven (December 1988). "The Game Hall of Fame". Macworld. Vol. 5, no. 12. PCW Communications, Inc. p. 122.

- ^ a b Banduch, Norman (May–June 1984). "Capsule Reviews". Space Gamer (69). Steve Jackson Games: 40.

- ^ a b Ewald, Bob (February–March 1987). "Computer Gaming". Space Gamer/Fantasy Gamer (77). Diverse Talents, Incorporated: 38–39.

- ^ Staff (November 1996). "150 Best (and 50 Worst) Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. No. 148. pp. 63–65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 94, 98.

- ^ Ludotique | Article | RPGGeek

- ^ "Jeux & stratégie HS 3". 1986.

- ^ ZDNet: Computer Gaming World: Reviews: Star Search

- ^ Browsing all Games – Matrix Games

- ^ Reach For The Stars: Interstellar (Spanish Edition) – Kindle edition by LTD, Greentwip. Children Kindle eBooks @ Amazon.com

External links

edit- Reach for the Stars at MobyGames

- The MS-DOS version of Reach for the Stars can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Gamespot review of Reach for the Stars 2000

- Matrix Games website