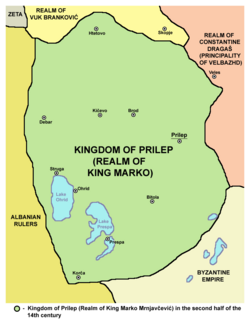

The Lordship of Prilep (Serbian: Господство Прилепа, romanized: Gospodstvo Prilepa), also known as the Realm of King Marko (Serbian: Област краља Марка, romanized: Oblast kralja Marka) or the Kingdom of Prilep (Serbian: Прилепско краљевство, romanized: Prilepsko kraljevstvo; Macedonian: Прилепско Кралство, romanized: Prilepsko Kralstvo; Bulgarian: Прилепско кралство, romanized: Prilepsko kralstvo; literally: 'Prilep Kingdom'), was one of the successor-states of the Serbian Empire, covering mainly the southern regions of the former empire, corresponding to western parts of present-day North Macedonia. Its central region of Pelagonia, with the city of Prilep, was held by lord Vukašin Mrnjavčević, who in 1365 became Serbian king and co-ruler of Serbian emperor Stefan Uroš V (1355–1371). After king Vukašin died at the Battle of Maritsa in 1371,[1] the realm was obtained by his son and designated successor (rex iunior) Marko Mrnjavčević, who took the title of Serbian king. At that time, capital cities of the Serbian realm were Skopje and Prizren,[2] but during the following years king Marko lost effective control over those regions, and moved his residence to Prilep. He ruled there until his death in the Battle of Rovine in 1395.[3] By the end of the same year, the Realm of late King Marko was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

Realm of King Marko | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1371–1395 | |||||||||||

Medieval Realm of King Marko | |||||||||||

| Capital | Prilep | ||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Christianity | ||||||||||

| Government | Kingdom | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 1371–1395 | King Marko (only) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||||

• Marko's inheritance | September 26, 1371 1371 | ||||||||||

• Subjugation by Bayezid I | 1395 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

History

editSince 1334,[4] the city of Prilep was under Serbian rule[5] and the surrounding region was held by Serbian feudal lord Vukašin Mrnjavčević, who was crowned the king of the Serbs and Greeks in 1365 as the co-ruler of last Serbian emperor Stefan Uroš V.[6] After the death of both Vukašin and Uroš in 1371, Vukašin's son Marko Mrnjavčević, who held the title of "Junior King" (rex iunior),[7] became the sole legal ruler of the Serbian Realm and took the title of Serbian king, but his power was contested by other Serbian feudal lords who gained control over other regions leaving Marko only with the areas in western half of Vardarian Macedonia, centered in Prilep.[8]

King Marko remained effective ruler only in the region of Prilep,[9] and was also nominally recognized by some other feudal lords in surrounding areas. All of them, including Marko, were forced to pay tribute to invading Ottoman Turks. The region and the city of Ohrid was ruled by the Albanian nobleman Andrea Gropa as an ally of Vukašin until the latter's death in 1371, and became de jure independent from the Lordship that year. Also in 1371, the Lordship lost the territories of Kostur, Prilep, and Dibër to Andrea Gropa and Andrea II Muzaka.

Since he became a vassal[10] of the Turkish Sultan, Marko Mrnjavčević was obligated to answer to the sultan's call in 1395 and take part in the Battle of Rovine where he was killed.[11][12] The Turks took the opportunity to conquer the region of Prilep, adding its territory to the Sanjak of Ohrid.

Since Marko, who styled himself as Serbian King, did not reduce his title to Prilep or any other local town or region, historians have used various terms for his domain. In Serbian historiography, it is called simply: the Lordship of King Marko (Serbian: Област краља Марка)[13] or the Domain of King Marko (Serbian: Држава краља Марка).[14]

Gallery

edit-

Dissolution of Serbian Empire in the late 14th century

-

Serbian King Marko, Lord of Prilep (1371-1395)

-

The Fortress of King Marko in Prilep

References

edit- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, p. 481.

- ^ Gavrilović 2001, p. 146.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 86.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, p. 451.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 363.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 380.

- ^ Temperley 1919, p. 97-98.

- ^ Nicol 1993, p. 275.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, p. 489.

- ^ Nicol 1993, p. 302.

- ^ Благојевић & Медаковић 2000, p. 231.

- ^ Ђурић 1984, p. 16.

Sources

edit- Благојевић, Милош; Медаковић, Дејан (2000). Историја српске државности. Vol. 1. Нови Сад: Огранак САНУ.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ђурић, Иван (1984). Сумрак Византије: Време Јована VIII Палеолога 1392-1448. Београд: Народна књига.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press. ISBN 9781899828340.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993) [1972]. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439916.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815624448.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331-1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884021377.

- Temperley, Harold W. V. (1919) [1917]. History of Serbia (PDF) (2 ed.). London: Bell and Sons.