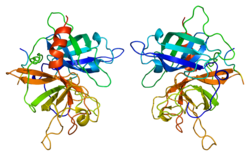

Tissue-type plasminogen activator, short name tPA, is a protein that facilitates the breakdown of blood clots. It acts as an enzyme to convert plasminogen into its active form plasmin, the major enzyme responsible for clot breakdown. It is a serine protease (EC 3.4.21.68) found on endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. Human tPA is encoded by the PLAT gene, and has a molecular weight of ~70 kDa in the single-chain form.[5]

| PLAT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | PLAT, T-PA, TPA, plasminogen activator, tissue type | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 173370; MGI: 97610; HomoloGene: 717; GeneCards: PLAT; OMA:PLAT - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tPA can be manufactured using recombinant biotechnology techniques, producing types of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) such as alteplase, reteplase, and tenecteplase. These drugs are used in clinical medicine to treat embolic or thrombotic stroke, but they are contraindicated and dangerous in cases of hemorrhagic stroke and head trauma. The antidote for tPA in case of toxicity is aminocaproic acid.

Medical uses

edittPA is used in some cases of diseases that feature blood clots, such as pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke, in a medical treatment called thrombolysis. The most common use is for ischemic stroke. It can either be administered systemically, in the case of acute myocardial infarction, acute ischemic stroke, and most cases of acute massive pulmonary embolism, or administered through an arterial catheter directly to the site of occlusion in the case of peripheral arterial thrombi and thrombi in the proximal deep veins of the leg.[6]

Ischemic stroke

editStatistics

editThere have been 12 large scale, high-quality trials of rtPA in acute ischemic stroke. A meta-analysis of these trials concluded that rtPA given within 6 hours of a stroke significantly increased the odds of being alive and independent at final follow-up, particularly in patients treated within 3 hours. However a significant mortality rate was noted, mostly from intracranial haemorrhage at 7 days, but later mortality was not significant amongst treated and non-treated patients.[7]

It has been suggested that if tPA is effective in ischemic stroke, it must be administered as early as possible after the onset of stroke symptoms, given that patients present to an ED in a timely manner.[7][8] Many national guidelines including the AHA have interpreted this cohort of studies as suggesting that there are specific subgroups who may benefit from tPA and thus recommend its use within a limited time window after the event. Protocol guidelines require its use intravenously within the first three hours of the event, after which its detriments may outweigh its benefits.

For example, the Canadian Stroke Network guideline states "All patients with disabling acute ischemic stroke who can be treated within 4.5 hours of symptom onset should be evaluated without delay to determine their eligibility for treatment" with tPA.[9] Delayed presentation to the ED leads to decreased eligibility; as few as 3% of people qualify for this treatment.[10] Similarly in the United States, the window of administration used to be 3 hours from onset of symptoms, but the newer guidelines also recommend use up to 4.5 hours after symptom onset, depending on the patient's presentation, past medical history, current comorbidities and medication usage.[11] tPA appears to show benefit not only for large artery occlusions but also for lacunar strokes. Since tPA dissolves blood clots, there is risk of hemorrhage with its use.[12][13]

Administration criteria

editUse of tPA in the United States in treatment of patients who are eligible for its use, have no contraindications, and arrival at the treating facility less than 3 hours after onset of symptoms, is reported to have doubled from 2003 to 2011. Use on patients with mild deficits, of nonwhite race/ethnicity, and oldest old age increased. However, many patients who were eligible for treatment were not treated.[14][15]

tPA has also been given to patients with acute ischemic stroke above age 90 years old. Although a small fraction of patients 90 years and above treated with tPA for acute ischemic stroke recover, most patients have a poor 30-day functional outcome or die.[16] Nonagenarians may do as well as octogenarians following treatment with IV-tPA for acute ischemic stroke.[17] In addition, people with frostbite treated with tPA had fewer amputations than those not treated with tPA.[18]

General consensus on use

editThere is consensus amongst stroke specialists that tPA is the standard of care for eligible stroke patients, and benefits outweigh the risks. There is significant debate mainly in the emergency medicine community regarding recombinant tPA's effectiveness in ischemic stroke. The NNT Group on evidence-based medicine concluded that it was inappropriate to combine these twelve trials into a single analysis, because of substantial clinical heterogeneity (i.e., variations in study design, setting, and population characteristics).[19] Examining each study individually, the NNT group noted that two of these studies showed benefit to patients given tPA (and that, using analytical methods that they think flawed); four studies showed harm and had to be stopped before completion; and the remaining studies showed neither benefit nor harm. On the basis of this evidence, the NNT Group recommended against the use of tPA in acute ischaemic stroke.[19] The NNT Group notes that the case for the 3-hour time window arises largely from analysis of two trials: NINDS-2 and subgroup results from IST-3. "However, presuming that early (0-3h) administration is better than later administration (3-4.5h or 4.5-6h) the subgroup results of IST-3 suggest an implausible biological effect in which early administration is beneficial, 3-4.5h administration is harmful, and 4.5-6h administration is again beneficial."[19] Indeed, even the original publication of the IST-3 trial found that time-window effects were not significant predictors of outcome (p=0.61).[20] In the UK, concerns by stroke specialists have led to a review by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.[21]

Pulmonary embolism

editPulmonary embolism (blood clots that have moved to the lung arteries) is usually treated with heparin generally followed by warfarin. If pulmonary embolism causes severe instability due to high pressure on the heart ("massive PE") and leads to low blood pressure, recombinant tPA is recommended.[22][23][24]

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activators (r-tPA)

edittPA was first produced by recombinant DNA techniques at Genentech in 1982.[25]

Tissue-type plasminogen activators were initially identified and isolated from mammalian tissues after which a cDNA library was established with the use of reverse transcriptase and mRNA from human melanoma cells. The aforementioned mRNA was isolated using antibody based immunoprecipitation. The resulting cDNA library was subsequently screened via sequence analysis and compared to a whole genome library for confirmation of specific protein isolation and accuracy. cDNA was cloned into a synthetic plasmid and initially expressed in E. coli cells, followed by yeast cells with successful results confirmed via sequencing before attempting in mammalian cells. The transformants were selected with the use of methotrexate. Methotrexate strengthens selection by inhibiting DHFR activity which then compels the cells to express more DHFR (exogenous) and consequently more recombinant protein to survive. The highly active transformants were subsequently placed in an industrial fermenter. The tPA which was then secreted into the culture medium was isolated and collected for therapeutic use. For pharmaceutical purposes, tPA was the first pharmaceutical drug produced synthetically with the use of mammalian cells, specifically Chinese hamster ovarian cells (CHO). Recombinant tPA is commonly referred to as r-tPA and sold under multiple brand names.[26][27]

| Product Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| Activase (Alteplase) | FDA-approved for treatment of myocardial infarction with ST-elevation (STEMI), acute ischemic stroke (AIS), acute massive pulmonary embolism, and central venous access devices (CVAD).[28] |

| Reteplase | FDA-approved for acute myocardial infarction, where it has more convenient administration and faster thrombolysis than alteplase. This is because it is a second generation engineered TPA, hence its half life is up to 20 minutes which allows it to be administered as a bolus injection rather than an infusion like Alteplase.[28] |

| Tenecteplase | Indicated in acute myocardial infarction, showing fewer bleeding complications but otherwise similar mortality rates after one year compared to Alteplase.[28] |

Interactions

editTissue plasminogen activator has been shown to interact with:

Function

edittPA and plasmin are the key enzymes of the fibrinolytic pathway in which tPA-mediated plasmin generation occurs.

tPA cleaves the zymogen plasminogen at its Arg561 - Val562 peptide bond, into the serine protease plasmin.[34]

Increased enzymatic activity causes hyperfibrinolysis, which manifests as excessive bleeding and/or an increase of the vascular permeability.[35] Decreased activity leads to hypofibrinolysis, which can result in thrombosis or embolism.

In patients with ischemic strokes, decreased tPA activity was reported to be associated with an increase in plasma P-selectin concentration.[36]

Tissue plasminogen activator also plays a role in cell migration and tissue remodeling.[citation needed]

Physiology and regulation

editOnce in the body, tPA has can cause the desired thrombolytic activity (see figure), or be inactivated and removed. In the bloodstream tPA has a half-life of 4 to 6 minutes.[39] tPA can be bound by a plasminogen activator inhibitor, resulting in inactivation of its activity. The protein is then removed from the bloodstream by the liver. One of the specific receptors responsible for this processes is a protein known as the LDL Receptor-Related Protein (LRP1), which clears tPA which is bound to the Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor 1 (PAI-1).[38] However, when present in a high enough concentration to counteract the effects of plasminogen activator inhibitor, tPA can bind plasminogen, cleaving off the bound plasmin from it. Plasmin, another type of protease, can either be bound by a plasmin inhibitor, or work to degrade fibrin clots, which is the main therapeutic pathway.[37]

Synaptic plasticity

edittPA is known to participate in some forms of synaptic plasticity, in particular long-term depression and consequently mediate some aspects of memory.[40]

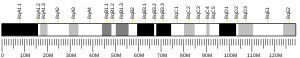

Genetics

editTissue plasminogen activator is a protein encoded by the PLAT gene, which is located on chromosome 8. The primary transcript produced by this gene undergoes alternative splicing, producing three distinct messenger RNAs.[41]

Gallery

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000104368 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031538 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Tissue plasminogen activator human". Sigma-Aldrich. 9 July 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Rivera-Bou WL, Cabanas JG, Villanueva SE (2008-11-20). "Thrombolytic Therapy". Medscape.

- ^ a b Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, del Zoppo G, Sandercock P, Lindley RL, et al. (June 2012). "Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischaemic stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 379 (9834): 2364–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60738-7. PMC 3386494. PMID 22632907.

- ^ DeMers G, Meurer WJ, Shih R, Rosenbaum S, Vilke GM (December 2012). "Tissue plasminogen activator and stroke: review of the literature for the clinician". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 43 (6): 1149–54. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.005. PMID 22818644.

- ^ Lindsay, Gubitz G, Bayley M, Hill MD, Davies-Schinkel C, Singh S, et al. (8 December 2010). "Hyperacute stroke management". Canadian best practice recommendations for stroke care. Canadian Stroke Strategy Best Practices and Standards Writing Group. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Stroke Network. pp. 55–84. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Hemmen T (April 2008). "Patient delay in acute stroke response". European Journal of Neurology. 15 (4): 315–6. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02083.x. PMC 2677077. PMID 18353121.

- ^ Davis SM, Donnan GA (June 2009). "4.5 hours: the new time window for tissue plasminogen activator in stroke". Stroke. 40 (6): 2266–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.544171. PMID 19407232.

- ^ Liu C, Xie J, Sun S, Li H, Li T, Jiang C, et al. (April 2022). "Hemorrhagic Transformation After Tissue Plasminogen Activator Treatment in Acute Ischemic Stroke". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 42 (3): 621–46. doi:10.1007/s10571-020-00985-1. PMID 33125600. S2CID 226218304.

- ^ Li Q, Han X, Lan X, Hong X, Li Q, Gao Y, et al. (December 2017). "Inhibition of tPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation involves adenosine A2b receptor activation after cerebral ischemia". Neurobiol Dis. 108: 173–182. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2017.08.011. PMC 5675803. PMID 28830843.

- ^ Bankhead C, Agus ZS (2013-08-23). "Clot-Busting Drugs Used More Often in Stroke". Medpage Today.

- ^ Schwamm LH, Ali SF, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, Saver JL, Messe S, et al. (September 2013). "Temporal trends in patient characteristics and treatment with intravenous thrombolysis among acute ischemic stroke patients at Get With The Guidelines-Stroke hospitals". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 6 (5): 543–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000095. PMID 24046398.

The frequency of IV tPA use among all AIS patients, regardless of contraindications, nearly doubled from 2003 to 2011. Treatment with tPA has expanded to include more patients with mild deficits, nonwhite race/ethnicity, and oldest old age

- ^ Mateen FJ, Nasser M, Spencer BR, Freeman WD, Shuaib A, Demaerschalk BM, et al. (April 2009). "Outcomes of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke in patients aged 90 years or older". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 84 (4): 334–8. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60542-9. PMC 2665978. PMID 19339651.

- ^ Mateen FJ, Buchan AM, Hill MD (August 2010). "Outcomes of thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in octogenarians versus nonagenarians". Stroke. 41 (8): 1833–5. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.586438. PMID 20576948.

- ^ Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT (2005). "An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite". J Trauma. 59 (6): 1350–1354. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000195517.50778.2e. PMID 16394908.; and repeated by Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, Cochran A, Edelman LS, Saffle JR (June 2007). "Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy". Archives of Surgery. 142 (6): 546–51, discussion 551–3. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.6.546. PMID 17576891.

- ^ a b c Newman D (March 25, 2013). "Thrombolytics for Acute Ischemic Stroke: No benefit found". NNT Group. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Sandercock P, Wardlaw JM, Lindley RI, Dennis M, Cohen G, Murray G, et al. (June 2012). "The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 379 (9834): 2352–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60768-5. PMC 3386495. PMID 22632908.

- ^ Brimelow A (2014-08-22). "Safety review into stroke clot-buster drug alteplase". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galiè N, et al. (November 2014). "2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism". European Heart Journal. 35 (43): 3033–69, 3069a–3069k. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283. PMID 25173341.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 144: Venous thromboembolic diseases: the management of venous thromboembolic diseases and the role of thrombophilia testing. London, 2012.

- ^ Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ (June 2008). "Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition)". Chest. 133 (6 Suppl): 71S–109S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0693. PMID 18574259.

- ^ "(TPA) Produced By Recombinant DNA Techniques". Biology Discussion. 1982-07-23. Archived from the original on 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2019-01-05.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Products of Recombinant DNA Technology". Biology Discussion. 2015-09-21. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ^ Pennica D, Holmes WE, Kohr WJ, Harkins RN, Vehar GA, Ward CA, et al. (January 1983). "Cloning and expression of human tissue-type plasminogen activator cDNA in E. coli". Nature. 301 (5897): 214–21. Bibcode:1983Natur.301..214P. doi:10.1038/301214a0. PMID 6337343. S2CID 39846803.

- ^ a b c Wanda L Rivera-Bou, José G Cabañas, Salvador E Villanueva (2017-05-02). "Thrombolytic Therapy: Background, Thrombolytic Agents, Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction". Medscape.

- ^ Tsurupa G, Medved L (January 2001). "Identification and characterization of novel tPA- and plasminogen-binding sites within fibrin(ogen) alpha C-domains". Biochemistry. 40 (3): 801–8. doi:10.1021/bi001789t. PMID 11170397.

- ^ Ichinose A, Takio K, Fujikawa K (July 1986). "Localization of the binding site of tissue-type plasminogen activator to fibrin". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 78 (1): 163–9. doi:10.1172/JCI112546. PMC 329545. PMID 3088041.

- ^ Zhuo M, Holtzman DM, Li Y, Osaka H, DeMaro J, Jacquin M, et al. (January 2000). "Role of tissue plasminogen activator receptor LRP in hippocampal long-term potentiation". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (2): 542–9. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00542.2000. PMC 6772406. PMID 10632583.

- ^ Orth K, Madison EL, Gething MJ, Sambrook JF, Herz J (August 1992). "Complexes of tissue-type plasminogen activator and its serpin inhibitor plasminogen-activator inhibitor type 1 are internalized by means of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (16): 7422–6. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.7422O. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7422. PMC 49722. PMID 1502153.

- ^ Parmar PK, Coates LC, Pearson JF, Hill RM, Birch NP (September 2002). "Neuroserpin regulates neurite outgrowth in nerve growth factor-treated PC12 cells". Journal of Neurochemistry. 82 (6): 1406–15. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01100.x. PMID 12354288.

- ^ Collen D (November 1987). "Molecular mechanism of action of newer thrombolytic agents". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 10 (5 Suppl B): 11B–15B. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80422-9. PMID 3117858.

- ^ Marcos-Contreras OA, Martinez de Lizarrondo S, Bardou I, Orset C, Pruvost M, Anfray A, et al. (November 2016). "Hyperfibrinolysis increases blood-brain barrier permeability by a plasmin- and bradykinin-dependent mechanism". Blood. 128 (20): 2423–2434. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-705384. PMID 27531677.

- ^ Wang J, Li J, Liu Q (August 2005). "Association between platelet activation and fibrinolysis in acute stroke patients". Neuroscience Letters. 384 (3): 305–9. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.090. PMID 15916851. S2CID 22979258.

- ^ a b "Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA)". diapharma.com. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ^ a b Gravanis I, Tsirka SE (February 2008). "Tissue-type plasminogen activator as a therapeutic target in stroke". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 12 (2): 159–70. doi:10.1517/14728222.12.2.159. PMC 3824365. PMID 18208365.

- ^ Khosravi A, Baharifar H, Darvishi MH, Karimi Zarchi AA (December 2020). "Investigation of chitosan-g-PEG grafted nanoparticles as a half-life enhancer carrier for tissue plasminogen activator delivery". IET Nanobiotechnology. 14 (9): 899–907. doi:10.1049/iet-nbt.2019.0304. PMC 8676530. PMID 33399124.

- ^ Calabresi P, Napolitano M, Centonze D, Marfia GA, Gubellini P, Teule MA, et al. (March 2000). "Tissue plasminogen activator controls multiple forms of synaptic plasticity and memory". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 12 (3): 1002–1012. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00991.x. PMID 10762331. S2CID 22764188.

- ^ PLAT_ plasminogen activator, tissue type [ Homo sapiens (human) ], NCBI gene database Gene ID: 5327 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/5327

External links

edit- History of Discovery: The Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Story, Collen, D., Lijnen, H.R.

- Genentech Press Release 1982 Archived 2018-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Tissue Plasminogen Activator from the American Heart Association

- Widening the Window : Strategies to buy time in treating ischemic stroke - Scientific American (August 2005)

- Study expands window for effective stroke treatment - explained on YouTube