The Indian National Army trials (also known as the INA trials and the Red Fort trials) was the British Indian trial by court-martial of a number of officers of the Indian National Army (INA) between November 1945 and May 1946, on various charges of treason, torture, murder and abetment to murder, during the Second World War.

Jawaharlal Nehru in Poona had announced that Congress would stand responsible for the trials. The committee formed for the defence of INA soldiers was formed by Congress Working Committee. It included Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Asaf Ali, Tej Bahadur Sapru, Kailash Nath Katju and others.[1]

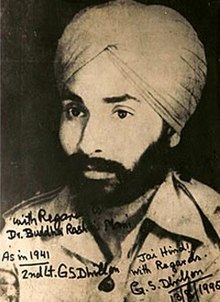

Initially, over 7,600 members of INA were set for trial but due to difficulty in proving their crimes the number of trials were significantly reduced.[2] Approximately ten courts-martial were held. The first of these was the joint court-martial of Colonel Prem Sahgal, Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon, and Major-General Shah Nawaz Khan. The three had been officers in the British Indian Army and were taken prisoner in Malaya, Singapore and Burma. They had, alongside a large number of other troops and officers of the British Indian Army, joined the Indian National Army and later fought in Burma alongside the Japanese military under the Azad Hind. These three came to be the only defendants in the trials who were charged with "waging war against the King-Emperor" (the Indian Army Act, 1911 did not provide for a separate charge for treason) as well as murder and abetment of murder. Those charged later only faced trial for torture and murder or abetment of murder.

The trials covered arguments based on military law, constitutional law, international law, and politics. Historian Mithi Mukherjee has called the event of the trial "a key moment in the elaboration of an anticolonial critique of international law in India."[3] As it was an army trial, Lt. Col. Horilal Varma Bar At Law & the then-Prime Minister of the Rampur State, along with Tej Bahadur Sapru, served as the lawyers for the defendants. These trials attracted much publicity, and public sympathy for the defendants, particularly as India was in the final stages of the Indian independence movement. Outcry over the grounds of the trial, as well as a general emerging unease and unrest within the troops of the Raj, ultimately forced the then-Army Chief Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck to commute the sentences of the three defendants in the first trial.

Indian National Army

editJapan, as well as South East Asia, was a major refuge for Indian nationalists living in exile before the start of World War II who formed strong proponents of militant nationalism and also influenced Japanese policy significantly. Although Japanese intentions and policies with regards to India were far from concrete at the start of the war, Japan had sent intelligence missions, notably under Major I Fujiwara, into South Asia even before the start of the World War II to garner support from the Malayan Sultans, the Burmese resistance and the Indian movement. These missions were successful in establishing contacts with Indian nationalists in exile in Thailand and Malaya, supporting the establishment and organisation of the Indian Independence League.

At the outbreak of World War II in South East Asia, 70,000 Indian troops were stationed in Malaya. After the start of the war, Japan's Malayan Campaign had brought under her control considerable numbers of Indian prisoners of war, notably nearly 55,000 after the Fall of Singapore. The conditions in the Japanese prisoner of war camps were notorious and led to some of the troops deserting, when offered release by their captors, and forming a nationalist army. From these deserters, the First Indian National Army was formed under Mohan Singh Deb and received considerable Japanese aid and support. It was formally proclaimed in September 1942 and declared the subordinate military wing of the Indian Independence League in June that year. The unit was dissolved in December 1942 after apprehensions of Japanese motives with regards to the INA led to disagreements and distrust between Mohan Singh and INA leadership on one hand, and the League's leadership, most notable Rash Behari Bose. The arrival of Subhas Bose in June 1943 saw the revival and reorganisation of the unit as the army of the Azad Hind government that was formed in October 1943. Within days of its proclamation in October 1943, the Azad Hind had been accorded recognition by Germany, Fascist Italy, Croatia, Thailand, Ba Maw's Burmese government, and some other Axis-allied nations, as well as receiving felicitations and gifts from the government of neutral Ireland and Irish republicans who had left British rule in 1912. The Azad Hind government declared war on Britain and America in October 1943. In Nov 1943, Azad Hind had been given a limited form of governmental jurisdiction over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which had been captured by the Japanese navy early on in the war. In the early part of 1944, INA forces were in action along with the Japanese forces in Imphal and Kohima area against Commonwealth forces, and later fell back with the retreating Japanese forces after the failed campaign. In early 1945, the INA's troops were committed against the successful Allied Burma Campaign. Most of the INA troops were captured, defected or fell otherwise into British hands during the Burma campaign by end of March that year and by the time Rangoon fell in May 1945, the INA had more or less ceased to exist although some activities continued until Singapore was recaptured.

At the conclusion of the Second World War, the government of British India brought some of the captured INA soldiers to trial on treason charges. The prisoners would potentially face the death penalty, life imprisonment or a fine as punishment if found guilty.

Early trials

editBy 1943 and 1944, courts martial were taking place in India of former personnel of the British Indian Army who were captured fighting in INA ranks or working in support of the INA's subversive activities. These did not receive any publicity or political sympathies and support until much later. The charges in these earlier trials were of "Committing a civil offence contrary to the Section 41 of the Indian Army Act,1911 or the Section 41 of the Burma Army Act" with the offence specified as "Waging War against the King" contrary to the Section 121 of the Indian Penal Code and the Burma Penal Code as relevant.[4]

With the release of Sarat Chandra Bose on 14 September 1945, the trials began to take an organised form.[5]

Public trials

editHowever, the number of INA troops captured by Commonwealth forces by the end of the Burma Campaign made it necessary to take a selective policy to charge those accused of the worst allegations. The first of these was the joint trial of Shah Nawaz Khan, Prem Sahgal and Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon, followed by the trials of Abdul Rashid, Shinghara Singh, Fateh Khan, Captain Malik Munawar Khan Awan, Captain Allah Yar Khan, and several other commissioned officers of the INA. The decision was made to hold a public trial, as opposed to the earlier trials, and given the political importance and significance of the trials, the decision was made to hold these at the Red Fort. Also, due to the complexity of the case, the provision was made under the Indian Army Act rule 82(a) for counsels to appear for defence and prosecution. The then Advocate General of India, Sir Naushirwan P Engineer was appointed the counsel for Prosecution.

INA Defence committee

editThe Indian National Congress made the release of the three defendants an important political issue during the agitation for independence of 1945–6. The INA Defence Committee was a committee established by the Indian National Congress in 1945 to defend those officers of the Indian National Army who were to be charged during the INA trials. Additional responsibilities of the committee also came to be the co-ordination of information on INA troops held captive, as well as arranging for relief for troops after the war. The committee declared the formation of the Congress' defence team for the INA and included Jawaharlal Nehru, Tej Bahadur Sapru, Bhulabhai Desai, R.B. Badri Das, Asaf Ali, Kanwar Sir Dalip Singh, Kailash Nath Katju, Bakshi Sir Tek Chand, P.N. Sen, Inder Deo Dua, Shiv Kumar Shastri, Ranbeer Chand Soni, Rajinder Narayan, Sultan Yar Khan, Narayan Andley and J.K. Khanna.[1]

The first trial

editThe first trial, that of Shah Nawaz Khan, Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon and Prem Sahgal was held between November and December 1945 against the backdrop of general elections in India with the Attorney General of India, Noshirwan P. Engineer as the chief prosecutor and two dozen counsel for the defence, led by Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru and fronted by Lt. Col Horilal Varma Bar At Law[6] All three of the accused were charged with "waging war against the king contrary to section 121 of the Indian Penal Code". In addition, charges of murder were leveled against Dhillon and of abetment to murder against Khan and Sahgal. The defendants were Punjabis who came from three different religions – one Hindu, one Sikh, and one Muslim – but all three elected to be defended by the defence committee set up by the Indian National Congress.[6]

Second trial

editThese were the trials of Captain Abdul Rashid, Captain Shinghara Singh Mann, Captain Munawar Khan, Captain Allah Yar Khan, Lieutenant Fateh Khan and some other officers. Shangara Singh was awarded the Sardar-e-Jung, the second-highest decoration bestowed by Azad Hind government for valour in combat, and the Vir-e-Hind medal. Subhas Chandra Bose himself gave Singh Mann his medals in Rangoon. He was captured by the British and held in a prison in Multan from January 1945 to February 1946. After his release, he returned to his family in the Punjab. In 1959, he settled in Vadodara, Gujarat, where he remained as of 2001. He died aged 113. Though Captain Allah Yar Khan and few of his coompanions were listed as POWs but in fact they escaped into jungle surrounding Singapore, fearing torture at the hands of the Japanese soldiers. They survived in jungle hunting and stalking on Japanese supply until October 1943 when they joined the second INA raised under Subhas Chandra Bose. At the time of trial, Captain Khan was under treatment at India-based General Hospital in Bangalore. In the wake of unrest over the charges of treason and glorification of INA soldiers in the first trial, the charges of treason was dropped. However, these officers were cashiered from army with rank reduction from the date of grant of emergency commission. The site of trial was also moved from the Red Fort to an adjoining building. [7]

Consequences of the trials

editBeyond the concurrent campaigns of noncooperation and nonviolent protest, this spread to include mutinies and wavering support within the British Indian Army. This movement marked the last major campaign in which the forces of the Congress and the Muslim League aligned together; the Congress tricolor and the green flag of the League were flown together at protests. In spite of this aggressive and widespread opposition, the court martial was carried out and all three defendants were sentenced to deportation for life. This sentence, however, was never carried out, as the immense public pressure of the demonstrations forced Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, to release all three defendants. A slogan popular during this time was, "Laal quile se aayi aawaz, Sahgal, Dhillon, Shahnawaaz". (transl. The sound coming from the Lal Red Fort says -Dhillion, Sehgal, Shahnawaz; May the three live long)[8]

During the trial, mutiny broke out in the Royal Indian Navy, incorporating ships and shore establishments of the RIN throughout India from Karachi to Bombay and from Vizag to Calcutta. The most significant if disconcerting factor for the Raj was the significant militant public support that it received. At some places, NCOs in the British Indian Army started ignoring orders from British superiors. In Madras and Pune, the British garrisons had to face revolts within the ranks of the British Indian Army.

Another Army mutiny took place at Jabalpur during the last week of February 1946, soon after the Navy mutiny at Bombay, which were both suppressed. It lasted about one week. After the mutiny, about 45 persons were tried by court martial. 41 were sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment or dismissal. In addition, a large number were discharged on administrative grounds. While the participants of the Naval Mutiny were given the freedom fighters' pension, the Jabalpur mutineers got nothing. They even lost their service pension.

Most of the INA soldiers were set free after cashiering and forfeiture of pay and allowance.[9]

Lord Louis Mountbatten, the head of Southeast Asia Command, ordered the INA memorial to its fallen soldiers to be demolished when Singapore was recaptured in 1945.[10] It has been suggested by some historians that Mountbatten's decision to demolish the INA memorial was part of a larger effort to prevent the spread of the socialist ideals of the INA in the political atmosphere of the Cold War and the decolonisation of Asia.[11][12] In 1995, the National Heritage Board of Singapore marked the place as a historical site. A Cenotaph has since been erected at the site where the memorial once stood.

After the war ended, the story of the INA and the Free India Legion was seen as so inflammatory that, fearing mass revolts and uprisings—not just in India, but across its empire—the British government forbade the BBC from broadcasting their story.[13] However, the stories of the trials at the Red Fort filtered through. Newspapers reported at the time of the trials that some of the INA soldiers held at Red Fort had been executed,[14] which only succeeded in causing further protests.

In popular culture

editThe 2017 period drama film Raag Desh is based on the INA trials.

See also

edit- Indian National Army

- INA Defence Committee, the legal defence team for the INA formed by the Indian National Congress in 1945.

- Shah Nawaz Khan, Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon and Prem Kumar Sahgal, defendants in the first INA trial.

- Malik Munawar Khan Awan, who commanded the 2nd INA Guerrilla Battalion during the Battle of Imphal.

- Habib-ur-Rehman, Subhas Chandra Bose's chief of staff.

- Lakshmi Sahgal, who commanded the Rani of Jhansi Regiment and was also the minister in charge of women's affairs in the Azad Hind government.

- Indian National Congress

References

edit- ^ a b Singh, Harkirat (2003). The INA Trial and the Raj. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 54. ISBN 978-81-269-0316-0.

- ^ Bayly, Christopher; Harper, Tim (2008). Forgotten Wars: The End of Britain's Asian Empire. Penguin Books Limited. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-14-190980-6.

- ^ Mukherjee, Mithi (2019). "The "Right to Wage War" against Empire: Anticolonialism and the Challenge to International Law in the Indian National Army Trial of 1945". Law and Social Inquiry. 44 (2): 420–443. doi:10.1017/lsi.2019.12. S2CID 191697854.

- ^ Stephen P. Cohen "Subhas Chandra Bose and the Indian National Army" Pacific Affairs Vol. 36, No. 4 (Winter, 1963) pp 411-429

- ^ Batabyal, R. (2005). Communalism in Bengal: From Famine To Noakhali, 1943-47. SAGE Series in Modern Indian History (in Indonesian). SAGE Publications. p. 191. ISBN 978-81-321-0205-2. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ a b Green, L.C. (January 1948). "The Indian National Army Trials". The Modern Law Review. 11 (4): 47–69. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.1948.tb00071.x. JSTOR 1090088.

- ^ Sharma, Ram Rakesh (1949): Azad Hind Fouj

- ^ "When INA soldier felt hurt in free India?". www.awazthevoice.in.

- ^ Nirad C. Chaudhuri "Subhas Chandra Bose-His Legacy and Legend" Pacific Affairs Vol. 26, No. 4 (December 1953), pp. 349-350

- ^ "Historical Journey of the Indian National Army". National Archive of Singapore.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Lebra, Joyce C., Jungle Alliance: Japan and the Indian National Army, Singapore, Asia Pacific Library

- ^ Borra R. Subhash Chandra Bose. Journal of Historical Review, 3, no. 4 (Winter 1982), pp. 407-439

- ^ Hitler's Secret Indian Army Last Section: "Mutinies" URL accessed on 8 August 2006

- ^ "Many I.N.A. men already executed, Lucknow" Archived 2007-08-09 at the Wayback Machine. The Hindustan Times, 2 November 1945. URL accessed 11 August 2006