This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

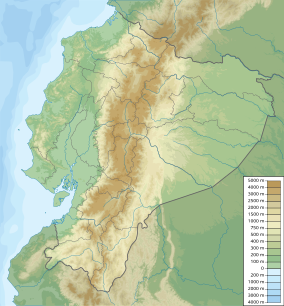

The Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve (Spanish: Reserva de Producción Faunística Cuyabeno) is the second largest reserve of the 56 national parks and protected areas in Ecuador.[1] It is located in the Putumayo Canton in the Sucumbíos Province and in the Aguarico Canton in the Orellana Province. It was decreed on 26 July 1979 as part of the creation of the national protected areas system based on the recommendations of the FAO report on the "National Strategy on the Conservation of Outstanding Wild Areas of Ecuador".[2]

| Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Ecuador Sucumbíos Province, Putumayo Canton; Orellana Province, Aguarico Canton |

| Coordinates | 0°07′00″S 75°50′00″W / 0.1167°S 75.8333°W |

| Area | 5900 km² |

| Established | 1979 |

From east to west, the elevation gently slopes from about 326 meters to slightly under 177 m above sea level and has an area of 590,112 hectares (5,900 km2 or 2,330 square miles).[3] The upper watershed being still close to the Andes, the weather seems slightly milder than more eastern parts of the Amazon, with temperatures a bit lower during the day and at night usually cooling to the low twenties (°C) or seventies (°F).

The Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve is an important nature reserve in Amazonia with rather unusual ecological characteristics. Located at the foothills of the Andes, it is different from any other Amazon protected area in the world. The area encompasses a poorly drained plain with a network of periodically inundated forests, lakes and creeks. Such conditions are rare so close to the Andes, where the drainage in the foothills prevents the development of swamps and lakes. Given its proximity to the mountains, combined with a slightly cooler and wetter climate it may be expected to have a partly different species composition than other areas in the upper Amazon watershed. As all protected areas in the Amazon region, the area has a high biodiversity, but possibly a bit lower than better drained protected areas like the neighbouring Yasuni National Park, which is considered the most diverse park in the world.[citation needed] However, such claims must be met with caution, as insufficient data of other areas exist to scientifically compare the diversity of areas. Moreover, to the incidental visiting tourist or even professional biologist such differences are irrelevant because all areas close to the Andes are incredibly rich in species.

Characteristics

editThere are nine major ecosystems in Cuyabeno:[4]

- (1) well-drained forest located on small hills in the upper watershed and the areas between the semi-inundated planes, particularly up-stream from the park entrance at "the Cuayabeno Bridge";

- (2) forests seasonally flooded by sediment-rich rivers, or varzea (Pires and Prance, 1985);[5]

- (3) seasonally flooded forests or swamps, traversed by sediment-poor black-water rivers with a vegetation dominated by Mauritia flexuosa palms;

- (4) semi-permanently inundated forests flooded by black-water rivers, or igapó (Pires and Prance, 1985) and dominated by macrolobium trees which are the homes to countless epiphytes, herons, blue and yellow macaws and hoatzins;

- (5) Submerged herbal vegetation found along lake and river shores; they consist of rooted water plants and shrubs that endure long-term submersion;

- (6) "coffee-and-milk" coloured sediment-rich rivers, the largest being the Río Aguarico;

- (7) "black-water" sediment-poor rivers, most notably the Zábalo River;

- (8) permanent lakes that rarely fall dry, primarily Zancudo Coche along the Río Aguarico;

- (9) semi-permanent lakes - the largest being the Cuyabeno Lake - that most of the years fall at least partly dry.

Black waters (both rivers and lakes) will turn sediment-laden during periods of high rainfall.

All large amazon mammals are present: the lowland tapirs, two species of deer, all Amazon cats, including jaguars and pumas, capibaras, two species of dolphins, manatees, both otter species, giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and neotropical otter (Lutra longicaudis), etc. Monkeys are represented by 10 species, while rodents and bats are represented by dozens of species.

The current number of registered bird species is under debate, some claiming 530 species while others suggest that more than 580 species have been observed, but nobody is known to keep solid records. At the peak of the wet season, thousands of hectares of forest become inundated, forming an El Dorado for an estimated number 350 fish species, two species of cayman, boa constrictors and anacondas, while countless frogs and toads sing their never-ending concerts. Dolphins have been seen swimming deep in the inundated forest during high water, as they follow the fishes.

There are two lake areas in the park. The nearest network of lakes is in the eastern part of the park, and can be conveniently reached from Lago Agrio over an asphalt road. The other lake network is located at the border with Peru, and requires some extensive travel, which is now organized by the Cofan tribe from their Cofan Lodge.[6] These lake and marsh areas have a different flora and fauna than the forests on the higher grounds in between these wetlands and at the upper watershed. While the inundated forests are relatively poor in species - but many more of each species, particularly wildlife -, the higher grounds have some of the highest number of trees per hectare on earth. On one location in neighbouring Yasuní National Park, 307 species of trees/hectare were counted.

The river system covers the rivers Aguarico, San Miguel and Cuyabeno along with their tributaries. Aforementioned two lake systems, both north of the Aguarico River have 13 lakes, while the largest lake, Zancudo Coche is South of the river. In the rainforest of the Amazon of Ecuador, it is difficult to speak of a rainy season, but a dryer season runs from somewhere mid-December to the end of the middle of March, but the beginning and the end of the dry season varies considerable. The climate corresponds to a wet tropical forest, with precipitation of about 3000 mm or 180 inches per year, and humidity ranging from 85% to 95%. The annual temperature oscillates around 25 °C or 77 °F.[7]

Ethnology

editThe Sionas live in the area of the upper Cuyabeno lakes network and along the Tarapuy river, while the Cofans, and the Secoyas live on the banks of the Aguarico, an affluent of the Amazon. The Secoyas, who originally lived within the borders of what is now the reserve, currently live just outside of the reserve. A few Siona, Secoya, and Cofan folk are still knowledgeable about the use of natural medicines, but unfortunately, that knowledge is fading away rapidly among the younger generations. Additionally, new arrivals have settled in the reserve, including smallholders, and Quichua Indians. Until the 1980s, these communities have mainly lived of fishing, farming and hunting. Since then, the life of the indigenous communities in the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve has changed due to improved access with roads built for oil exploitation and earnings from ecotourism.

References

edit- ^ "Ambiente-agua".

- ^ "Estrategia Preliminar para la Conservación de Áreas Silvestres Sobresalientes del Ecuador" (PDF). February 1976. UNDP/FAO-ECU/71/527 – via birdlist.org.

- ^ "Cuyabeno Fauna Production Reserve | Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas del Ecuador".

- ^ "CUYABENO NATIONAL RESERVE [ECUADOR's AMAZON]".

- ^ Pires, J.M.; Prance, Ghillean T. (1985). "The vegetation types of the Brazilian Amazon". In Prance, Ghillean T.; Lovejoy, Thomas E. (eds.). Key Environments: Amazonia. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. ISBN 9780080307763 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "6 Best Amazon Rainforest Vacations, [Review]".

- ^ "A local's guide to Ecuador". CN Traveller. 2021-09-03. Retrieved 2021-09-05.