Resistance in the German-occupied Channel Islands

During the German occupation of the Channel Islands, there was limited resistance. The islands had a very high number of German soldiers compared to the civilian population, one soldier for every 2-3 civilians, which reduced options; this linked to the severe penalties imposed by the occupiers meant that only forms of non-lethal resistance were used by the population. Even so, over twenty civilians died for resistance against the occupiers.

Background

editFrom the British declaration of war on Germany in September 1939 until May 1940, a number of Channel Islanders had left to volunteer for the armed forces in Britain or to work in associated war industries, whilst British people came to the Channel Islands on holiday.

On 10 May 1940, Nazi Germany invaded France and the Low Countries. The Blitzkrieg (Lightning War) tactics took the Western powers by surprise. By the time of the resignation of the French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud on 16 June, it was obvious that Germany victory in the Battle of France was inevitable. In the Channel Islands, civilians worried about the consequences of remaining on the islands but, to avoid panic, were told by the authorities to stay put. Senior officials were ordered to stay to maintain order and to keep the Government functioning. On 15 June, the British government decided to demilitarise the islands, evacuating the British garrisons and leaving them undefended. The Germans were not informed, however, and on 28 June German Heinkel bombers from Cherbourg bombed and strafed the harbours of Saint Peter Port and Saint Helier killing 38 and wounding 45 civilians.[1]: 32 [2]: 50 [3]: 36 Evacuation boats for civilians only became available on 20 June and again, to stop a panic, people were still told to remain where they were and that only women and children should be taken. Only when the Lieutenant Governors of the islands evacuated was the recommendation relaxed. The last official ships sailed on 23 June.[2]: 51

In total 17,000 from Guernsey, 6,600 from Jersey and all the 1,400 on Alderney travelled to England.[4] The size of the evacuation inevitably reduced the pool of potential active resistors in the Islands once the Germans landed and began their occupation on 30 June 1940.

German occupation authorities

editThe German occupation administration in the Channel Islands reported to Paris, the headquarters of Army Group A where two branches, the Verwaltungsstab for civilian matters and the Kommandostab who dealt with military matters, controlled occupied France.

The German military Police, the Feldgendarmerie (Field Police) were in operation on both Islands. Their line of reporting was directly to the Field Commander in each Island and dealt with all crimes as well as routine traffic control and guarding installations. They formed working relationships with the civilian policemen as their scope of operations frequently overlapped.[2]: 84 The Geheime Feldpolizei (Secret Field Police) were tasked with detecting sabotage and subversion and reported to the SS.[2]: 84

Aside from the various security forces, a large number of German troops were also garrisoned in the Islands. In October 1944, there were 12,000 soldiers in Jersey and 13,000 in Guernsey. This should be compared to the civilian populations of 39,000 in Jersey and 23,000 in Guernsey: ratios of 1:3 and 1:2.[2]: 158 By comparison, there were a mere 100,000 Germans in the whole of the German-zone in France in December 1941,[5] responsible for a population of over 25 million (a ratio of 1:250), although the ratio later reduced to around 1:80. Over 17,000 private houses were used for billeting German soldiers in 1942.[6]: 253

Growth of resistance

editDemographics

editIn July 1940, the few military personnel trapped on the Islands were identified and sent to POW camps.[2]: 229 A year later, all trained army officers in the Islands, many being retired British people who would be deported from the Islands to Germany in 1942, or were Islanders who had served in World War I, many of these holding positions of authority in the Island Governments were identified. What was left were elderly veterans and civilian men and women, with no weapons or communications with Britain to give guidance.

Scholar Louise Willmot said that the percentage of the population actively resisting German occupation in other European countries was 0.6 to 3 percent and that the percentage of the islander population participating in acts of active resistance was comparable.[7] From a wartime population of 66,000 in the Channel Islands[8] a total of around 4,000 islanders were sentenced for breaking laws (around 2,600 in Jersey and 1,400 in Guernsey), although many of these were for criminal acts rather than resistance; 570 prisoners were sent to continental prisons and camps, and at least 22 persons from Jersey and 9 from Guernsey did not return.[9] Willmott estimated that over 200 people in Jersey provided material and moral support to escaped forced workers, including over 100 who were involved in the network of safe houses sheltering escapees.[7]

Organisation

editThe British government had ordered the Islands leaders and crown officers to remain in the Islands and do their duties in the interest of the inhabitants.[2]: 50 The British government had further demilitarised the Islands in late June 1940 and did little or nothing to foster or help any form of resistance in the Islands.[1]: 175

Resistance efforts were rarely organised; those that were, were organised through the traditional social networks of the Islands. The absence of political parties and the weakness of trade unions meant that political networks that facilitated resistance in other countries were lacking in the Channel Islands. Patriotic pride was bound up more in survival than in imagery of resistance. Some individuals who were later eligible for awards from the Soviet Union for their help towards Soviet prisoners were reluctant to participate in what they considered propaganda. Personal contacts between fugitive prisoners and the families that had helped them were in some cases maintained after the war despite the Cold War and the barriers to communication. Communists and conscientious objectors, groups regarded with disdain by many Islanders, were among those who identified with and sympathised with fugitive workers. Others sympathised on compassionate grounds; some offering help in the way they hoped members of their own family caught up in the war might be treated by others wherever they might be. Some saw helping fugitives as the only practical way of defying the Germans in the face of obstacles to more active forms of resistance. In other occupied countries, those who sheltered victims of Nazism were generally offering help to local deserters from forced service and Jews – mostly their friends, neighbours, family, or people from the same social milieu. With so few Jews in the community, and the forced labour situation being different, in the Channel Islands those who helped fugitives were generally harbouring strangers with whom they did not share a language.[7]

Norman Le Brocq of the Jersey Communist Party (JCP) led a resistance group called Jersey Democratic Movement (JDM). The resistance helped many of the Soviet forced labourers that the Germans had brought to the island. JDM, the JCP and Transport and General Workers' Union distributed propaganda. With the aid of a German deserter, Paul Mulbach, they apparently had some success in turning the soldiers of the garrison against their masters, including most notably the highest military authority in the Islands, Huffmeier. There is some evidence to suggest that they had even set a date for this mutiny (1 May 1945) but that it was rendered pointless by the suicide of Adolf Hitler. Peter Tabb suggests that they were involved in the blowing up of the Palace Hotel and of separate ammo dumps; in fact it is more likely that their involvement was to set fire to the hotel, and the German efforts to put out the subsequent blaze by using dynamite to create a breach between the flames were misjudged and set off charges in a neighbouring ammo dump. Nevertheless, the JCP do seem to have made many plans for organised resistance.[10]

Escapees

editA total of 225 islanders, such as Peter Crill, escaped from the islands to England or France: 150 from Jersey, and 75 from Guernsey.[9] A high number of people drowned or failed to escape and were captured.[11] Five boats left Guernsey the day after the occupation started.[4] The number of escapes increased after D-Day, when conditions in the islands worsened as supply routes to the continent were cut off, the desire to join in the liberation of Europe increased and the route shortened.[12]: 128

In May 1942, three youngsters, Peter Hassall, Maurice Gould, and Denis Audrain, attempted to escape from Jersey in a boat (Audrain drowned, Hassall and Gould were imprisoned in Germany, where Gould died).[9] Following this escape attempt, restrictions on small boats and watercraft were introduced and after each attempt, further temporary bans and restrictions and penalties were imposed.[13]

Some escapees carried information on the Islands fortifications and the defending forces as well as messages.[14]: 67 Successful escapees were debriefed to obtain as much information as possible on conditions in the Islands.[2]: 158 One escapee was met by HM Customs and Excise who charged him 10/- import duty on his dinghy.[2]: 115

Once the Cherbourg peninsula was in allied control, an "easier" escape route became possible. Amongst those heading to France were two American officers, Captain Ed Clark and Lieutenant George Haas, who escaped from the prisoner of war camp at St. Helier on 8 January 1945. Assisted by several residents, including Deputy W.J. Bertram of BEM East Lynne, Fauvic, they crossed to the Cotentin Peninsula in a small boat on the night of 19 January 1945. The penalty for anyone caught helping them was death.[1]: 106

Forms of resistance

editResistance involved passive resistance, acts of minor sabotage, sheltering and aiding escaped slave workers, and publishing underground newspapers containing news from BBC Radio. Penalties if caught could be severe.

Resistance started very early in the occupation; a local newspaper published on 1 July 1940 the "Ordre of the Kommandant of the German Forthes in occupation of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, Alderney and Sarc", using the exact spelling they were given.[15]

There were no radio transmitters available to civilians in the islands as transmitters required licences,[16]: 216 so all owners were known to the authorities, nor was any attempt made by the British to deliver a radio to the islands. The islands stayed isolated and out of contact with Britain throughout the occupation.

Inherent resistance

editThe physical location of the Islands, the loyalty of the Islanders to the British Crown and the fact that it was the only part of "British" territory that was captured by the German forces,[17] resulted in a strong desire, especially by Hitler himself, to defend and spend excessive amounts of time and energy on the Islands. The "Festung" books, hand created with coloured drawings for Hitler, showing in great detail the Islands defences are testament to his interest in the Islands.

An important military consequence of the occupation and fortification of the Channel Islands was the deployment of very large numbers of German troops and high usage of slave labour relative to the minor amount of military resources and strategic value they held. This became evident in July 1944, shortly after the D-Day landings and the subsequent St Lo breakout. As the Allies simply chose to bypass the Islands, and many of the arguably far more militarily-significant French coastal ports such as St Nazaire, Lorient, Brest, and St Malo as well, all of which Hitler had previously ordered to be defended and held at all costs and consequently all of which were all heavily garrisoned, this meant that well over 100,000 German troops which could otherwise have served to help to defend Occupied France (and subsequently Germany itself), at a time when Germans forces on the Western Front were suffering from a massive shortage of manpower, were tied down in positions which were essentially militarily useless. The German historian Joachim Ludewig estimates from his study of German archival records that in the middle of 1944 the Channel Islands occupation alone was responsible for over 30,000 such misdeployed troops.[18] Around 500 Germans had died in the Channel Islands.[2]: 218

Passive resistance

editSome defiance or passive resistance was very minor and personal to each activist, from crossing a road to avoid meeting a German soldier on a pavement, knocking on a door using the morse code letter V •••-, breaking a used matchstick into a "V" shape, to providing a crust of food to a starving forced worker.

The Guernsey Evening Press and The Star, subject to censorship from the German authorities, continued to publish, eventually on alternate days given the shortage of materials and staff available. After the Germans temporarily removed the editor of The Star, Bill Taylor, from his position, following an article which they deemed offensive, it was edited by Frank Falla. Falla was a key member of the Guernsey "Resistance", being involved in the Guernsey Underground News Sheet (which went by the acronym GUNS). GUNS published BBC news, illegally received, typed on a single news sheet using tomato packing paper. According to his memoirs, through strategic placement of stories handed to him by the German authorities in The Star, he allowed islanders to distinguish easily between German news and stories emanating from Guernsey journalists. Falla was eventually betrayed by an Irish collaborator and, along with his peers who helped to produce GUNS, was deported to Germany. Falla survived, though other members of the organisation did not return from Germany.[19]

A shortage of coinage in Jersey (partly caused by occupying troops taking away coins as souvenirs) led to the passing of the Currency Notes (Jersey) Law on 29 April 1941. A series of two shilling notes (blue lettering on orange paper) was issued. The law was amended on 29 November 1941 to provide for further issues of notes of various denominations, and a series of banknotes designed by Edmund Blampied was issued by the States of Jersey in denominations of 6 pence (6d), 1, 2 and 10 shillings (10/–) and 1 pound (£1). The 6d note was designed by Blampied in such a way that the word six on the reverse incorporated an outsized "X" so that when the note was folded, the result was the resistance symbol "V" for victory.[20] A year later he was asked to design six new postage stamps for the island, in denominations of ½d to 3d. As a sign of resistance, he cleverly incorporated into the design for the 3d stamp the script initials GR (for Georgius Rex) on either side of the "3" to display loyalty to King George VI.[21] Edmund Blampied forged stamps for documents for fugitives.[7]

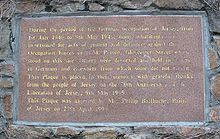

In June 1943 the bodies of two RAF NCO's washed ashore in Jersey, the military funeral attracted large crowds along the route[22]: 50 then in November, soon after the sinking of HMS Charybdis and HMS Limbourne on 23 October 1943, the bodies of 21 Royal Navy and Royal Marines men were washed up in Guernsey. The German authorities buried them with full military honours. The funerals became an opportunity for some of the islanders to demonstrate their loyalty to Britain and their opposition to the occupiers: around 5,000 of the 23,000 Islanders attended the funeral, laying some 900 wreaths – enough of a demonstration against the Occupation for subsequent military funerals to be closed to civilians by the German occupiers.[23] Every year a commemoration service is held, which is attended by survivors of the action and their relatives, the Guernsey Association of Royal Navy and Royal Marines, Sea Cadets, St John Ambulance Brigade, the Police and the Red Cross and representatives of the Royal Navy.[23][24]

Islanders joined in Churchill's V sign campaign by daubing the letter "V" (for Victory) over German signs, resulting in the German troops painting their own "V" signs.[11]: 173 "V" signs went undercover with badges being made from a shilling showing the king's head surmounting a "V" that could be worn under the lapel and shown to select people; one of the badges was even sold to and worn by a German soldier.[25] Scouting was banned, but continued undercover,[26] as did the Salvation Army after it was banned.

The making and concealing of crystal sets expanded when radios were confiscated, taking earphones from public phones and using common objects like metal bedsteads as aerials.[6]: 87

One side effect of the occupation and local resistance was an increase in the speaking of local languages (Guernésiais in Guernsey and Jèrriais in Jersey). As many of the German soldiers were familiar with both English and French, the indigenous languages enjoyed a brief revival as islanders sought to converse without the Germans understanding.

Active resistance

editThere was no armed resistance movement in the Channel Islands. This has been ascribed to a range of factors including the demilitarisation of the Islands by the British government in 1940, the physical separation of the islands, the density of troops (up to one German for every two islanders), the small size of the islands precluding any hiding places for resistance groups,[1]: 174 and the absence of the Gestapo from the occupying forces. Moreover, much of the population of military age had already joined the British or French armed forces.

Minor acts of sabotage, such as cutting a telephone wire, which could be repaired in an hour, would result in collective punishment with men in the area required to stand guard duty for several nights,[27]: 105 [28]: 201 a breach of the Hague Convention on military law.[28]

Marie Ozanne, a Major in the Salvation Army, did not agree with the German Order to ban preaching in the open air or to close the "Army" down,[3]: 43 nor did she agree with the inhumane treatment meted out to the workers building the fortifications. Her repeated protests about the prisoners to the German authorities resulted in her imprisonment. She died in April 1943 at the age of 37. Although she achieved little at the time, her show of courage, decency and defiance, suppressed at the time by the Germans, was an example to all.[1]: 179

The Reverend Cohu would deliver his sermon in church each week, in which he would add items of news obtained from the BBC to cheer up his flock. He was arrested in the middle of a sermon in March 1943. Shipped to Germany and put in an SS camp, starved, he died in September 1944.[1]: 195

Two French lesbian artists, one of whom was Jewish, Lucille (also known as Claude) Cahun and Suzanne Malherbe, both having failed to register properly in 1940, produced anti-German leaflets from English-to-German translations of BBC reports, pasted together to create rhythmic poems and harsh criticism. The couple then dressed up and attended many German military events in Jersey, and put the leaflets in soldiers' pockets, on their chairs or "hidden" inside cigarette packets also encouraging soldiers to shoot their officers. Denounced by a neighbour, they were captured by the Germans in late summer of 1944, condemned to death, the intervention of the Jersey Bailiff succeeded in getting the sentence commuted to prison.[1]: 191

After curfew one night, two Police constables saw a very drunk German soldier staggering through town, and gave him a quick shove which sent him flying down a steep flight of granite steps. The Police reported a drunk soldier lying on the steps and after an ambulance had taken him away, the policemen were given some cigarettes from a grateful German for helping their comrade.[27]: 106 A minor assault on a German soldier could result in 3 months jail and a fine of 2 years salary.[28]: 203

Jersey's Medical Officer of Health, Dr Noel McKinstry, a Northern Irelander by birth, was active in providing his own home to shelter fugitives, in providing forged papers and forging statistics in order to be able to issue extra supplies. Officials of the Parish of Saint Helier provided ration cards and identity cards for fugitives. Some individuals taught fugitives English; eventually some fugitives were proficient enough in English to move around and to be able to participate in activities without detection.[7]

Miriam Milbourne risked her life to save a rare breed, a small herd of Golden Guernsey goats, by hiding them for years.[29] A farmer hid his bull in a haystack for years, only letting it out at night.[30]: 160

Because of the small size of the islands, most resistance involved individuals risking their lives to save someone else.[31] The British government followed a policy of not encouraging resistance in the Channel Islands.[9] Reasons for this British policy included the fact that resistance within such "parochial limits" was unlikely to be effective, would be of no direct use to the war effort, and the risk of violent retaliation against British citizens in the Islands was not something the wider British population would be likely to accept (as opposed to the hostage-shootings that were occurring in continental Europe).[9]

On 9 March 2010 the award of British Hero of the Holocaust was made to 25 individuals posthumously, including 4 Jerseymen, by the United Kingdom government in recognition of British citizens who assisted in rescuing victims of the Holocaust. The Jersey recipients were Albert Bedane, Louisa Gould, Ivy Forster and Harold Le Druillenec. It was, according to historian Freddie Cohen, the first time that the British Government recognised the heroism of islanders during the German occupation.[31]

Public attitudes

editAttitudes to German rule changed as the Occupation went on. At first, the Germans followed a policy of presenting a non-threatening presence to the resident population for its propaganda value ahead of a possible invasion and occupation of the United Kingdom.[32] Many Islanders were willing to go along with the necessities of Occupation as long as they felt the Germans were behaving in a correct and legal way. Two events particularly jolted many Islanders out of this passive attitude: the confiscation of radios, and the deportation of large sections of the populations.[7]

Listening to BBC Radio had been banned in the first few weeks of the occupation and then (surprisingly given the policy elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe) tolerated for a period before being once again prohibited. In 1942 the ban became draconian, with all radio listening (even to German stations) being banned by the occupiers, a ban backed up by the confiscation of wireless sets.[16]: 223

Denied access to BBC broadcasts, the populations of the Islands felt increased resentment against the Germans and increasingly sought to undermine the rules. Hidden radio receivers and underground news distribution networks spread. Nevertheless, many islanders successfully hid their radios (or replaced them with homemade crystal sets) and continued listening to the BBC despite the risk of being discovered by the Germans or being informed on by neighbours.[33] The regular raids by German personnel hunting for radios further alienated the occupied civilian populations.[7]

In September 1941 the British War Cabinet ordered German civilians in Persia to be interned, which was against international law. Hitler in response ordered the internment of British civilians, most of whom were to be found in the Channel Islands; 10 British for 1 German and shipped to the Pripet Marshes. The Islands had been ordered to carry out a census, so the Germans knew the place of birth of every Islander. Such a reprisal act was against international law. The Germans in the islands delayed, however in August 1942 Hitler was reminded of the issue by a Swiss trying to arrange an exchange of prisoners for British civilians and reissued his order when he found his initial 1941 order had not been acted upon.[1]

The deportations of 2,058 men, women, children and babies in September 1942, which triggered suicides in Guernsey, Sark and Jersey,[1] sparked the first mass demonstrations of patriotism of the Occupation. The illegality and injustice of the measure, which contrasted with the Germans' earlier showy insistence on legality and correctness, outraged those who remained behind and encouraged many to turn a blind eye to the resistance activities of others in passive support.[7][34] The deportees were sent to camps in Germany, sailing off singing patriotic songs, including "There'll Always Be an England" and "God Save the King".[1]: 84

Further resentment was caused by a second deportation of 187 that occurred in early 1943, following a commando raid on Sark, Operation Basalt, which resulted in captive German soldiers being killed while trying to escape.

The sight of brutality against slave workers brought home to many Islanders the reality of Nazi ideology behind the punctilious façade of the Occupation. Forced marches between camps and work sites by wretched workers and open public beatings rendered visible the brutality of the régime.[7]

The rotation of German soldiers, with first-grade men being gradually downgraded until many soldiers were non-German, ex-Russian prisoners appearing in German uniform resulted in a reduction in morals and an increase in crimes, often linked to the soldiers' hunger, including murders.[35]: 26

Following the Normandy invasion in June 1944, many changes to attitude occurred, prisoners could no longer be sent to France, similarly, no supplies could be received into the Islands. Both sides realised that the writing was on the wall for Germany and the Island authorities could become less subservient and more demanding in requests, such as the request for Red Cross assistance. The Germans were agreeing to more of these requests. Even Britain changed its attitude, previous requests for Red Cross help being refused with Churchill, on 27 September 1944, writing a note saying: "Let them starve. No fighting. They can rot at their leisure".[1]: 100

The Channel Islands had been bypassed by the Battle of Normandy, leading to wide-spread hunger during the winter of 1944–1945. Each arrival of the SS Vega gave brief opportunities to celebrate. During April 1945 British flags started to appear, and the public was warned not to aggravate the Germans. The true feelings of Islanders burst out into the open on 9 May 1945 when they were finally liberated.[36]

There is no doubt that the Islands were an embarrassment to Churchill. His "We will fight them on the beaches" speech was certainly not taken up in the Channel Islands. However it was the British Government that had abandoned the Islands and declared them neutral territory in June 1940.[37]

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth made a special visit to the Islands on 7 June 1945.[38]

Retribution

editOn 13 December 1940, sixteen young Frenchmen, soldiers on probation, set out in a boat from occupied Brittany with the intention of joining the Free French forces in England. Failure of navigation skills and rough seas led them to land in Guernsey, thinking it was the Isle of Wight. They landed singing the Marseillaise only to be captured straightaway by German sentries. Six of them were transferred to Jersey for trial, where François Scornet (1921–1941)[39] was nominated as the ringleader and at a German military trial in the States Building in Jersey was sentenced to death. He was shot by firing squad on 17 March 1941[40] in the grounds of Saint Ouen's Manor.[9]

Louisa Gould hid a wireless set and sheltered an escaped Soviet prisoner. Betrayed by an informer at the end of 1943, she was arrested and sentenced on 22 June 1944. In August 1944 she was transported to Ravensbrück where she died on 13 February 1945.[41] In 2010 she was posthumously awarded the honour British Hero of the Holocaust.

Anyone captured for a resistance activity faced prison, sometimes on the Island, however some were sent off Island. For listening to the BBC a sentence of 4 weeks in the local prison followed by deportation to a prison in France and then on to Germany as a forced labourer for years was not unknown.[42] This was mild compared to the SS "Nacht und Nebel" directive of December 1941, which denounced even a sentence of hard labour for life as a "sign of weakness", and recommended death or disappearance for any civilian who sought to resist.[1]: 111

In July 1941 Colonel Knackfuss issued a notice warning that anyone caught undertaking espionage, sabotage or high treason, the penalty would be death. In addition and more worrying was the notice that in the event of any attacks against communications, such as cutting telephone wires, the Germans would have the right to nominate anyone in the area and give them a death sentence.[27]

The highest profile person to be caught was Ambrose Sherwill, President of the Controlling Committee in Guernsey, sent to Cherche-Midi prison in Paris for helping two British soldiers.[43]: 134 Lt Hubert Nicolle and Lt James Symes, both Guernsey men, landed in plain clothes to "spy" on the Germans however they became stranded. His efforts got them treated as PoWs rather than spies. The Germans in France changed the decision and would have had them shot had it not been for the German Commandant in Guernsey who managed to reverse the decision at a "Court of Honour", as he had given his word regarding their treatment. They were moved to a PoW camp.[44]

Harold Le Druillenec, brother of Louisa May Gould, was arrested on 5 June 1944 for trying to help an escaped Russian prisoner of war and having a radio, his sentence took him to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp for ten months and he was the only British survivor from that camp. He commented that: All my time here was spent in heaving dead bodies into the mass graves kindly dug for us by 'outside workers' for we no longer had the strength for that type of work which, fortunately, must have been observed by the camp authorities. Jungle law reigned among the prisoners; at night you killed or were killed; by day cannibalism was rampant.[45]

A number of Islanders died as a result of their resistance activities including:

Jersey

- Clifford Cohu: clergyman, arrested for acts of defiance including preaching against the Germans. Died in Spergau.[35]

- Arthur Dimmery: sentenced for digging up a buried wireless set for Saint Saviour wireless network. Died in Laufen.[46]: 132

- Maurice Jay Gould: arrested following a failed attempt to escape to England. Died in Wittlich.[35]

- Louisa Gould: arrested for sheltering an escaped slave worker.[41] Died in Ravensbrück concentration camp.[35]

- James Edward Houillebecq: deported following discovery of stolen gun parts and ammunition. Died in Neuengamme concentration camp.[35]

- Frank René Le Villio: deported for serious military larceny (stealing a motorbike). Spent time in Belfort, Neuengamme and Belsen camps.[47] Died in hospital in Nottingham shortly after the end of the war.[46]: 138

- William Howard Marsh: arrested for spreading BBC news. Died in Naumburg prison.[35]

- Edward Peter Muels: arrested for helping a German soldier to desert after killing his officer.[46]: 139

- John Whitley Nicolle: sentenced as ringleader of Saint Saviour wireless network. Died in Dortmund.[35]

- Léonce L'Hermitte Ogier: advocate, arrested for possession of maps of fortifications and a camera, died in internment following imprisonment.[46]: 145

- Frederick William Page: sentenced for failing to surrender a wireless set. Died in Naumburg-am-Saale penal prison.[46]: 154

- Clarence Claude Painter: arrested following a raid that discovered a wireless set, cameras and photographs of military objects. Died on train to Mittelbau-Dora.[46]: 155

- Peter Painter: son of Clarence Painter, arrested with his father when a pistol was found in his wardrobe. Died in Natzweiler-Struthof.[35]

- June Sinclair: hotel worker, sentenced for slapping a German soldier who made improper advances. Died in Ravensbrück concentration camp.[46]: 157

- John (Jack) Soyer: sentenced for possession of a wireless, escaped from prison in France and died fighting with a Maquis unit.[46]: 157

- Joseph Tierney: first member of Saint Saviour wireless network to be arrested. Died in Celle.[35]

Guernsey

- Sidney Ashcroft: convicted of serious theft and resistance to officials in 1942.[34] Died in Naumburg prison.

- Joseph Gillingham: was one of a number of islanders involved in the Guernsey Underground News Service (GUNS).[34] Died in Naumburg prison.

- John Ingrouille: aged 15, found guilty of treason and espionage and sentenced to five years hard labour.[34] Died in Brussels after release in 1945.

- Charles Machon: brainchild of GUNS.[11]: 112 [34] Died in Hamelin prison.

- Percy Miller: sentenced to 15 months for wireless offences.[34] Died in Frankfurt prison.

- Marie Ozanne: refused to accept the ban placed on the Salvation Army.[34] Died in Guernsey hospital after leaving prison.

- Louis Symes: sheltered his son 2nd Lt James Symes, who was on a commando mission to the island.[34] Died in Cherche-Midi prison.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Nettles, John (October 2012). Jewels and Jackboots. Channel Island Publishing; 1st Limited edition (October 25, 2012). ISBN 978-1905095384.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tabb, Peter (2005). A peculiar occupation. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711031135.

- ^ a b Chapman, David (2009). Chapel and Swastika: Methodism in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940-1945. ELSP. ISBN 978-1906641085.

- ^ a b Hamon, Simon (30 June 2015). Channel Islands Invaded: The German Attack on the British Isles in 1940 Told Through Eye-Witness Accounts, Newspapers Reports, Parliamentary Debates, Memoirs and Diaries. Frontline Books, 2015. ISBN 9781473851603.

- ^ "The Civilian Experience in German Occupied France, 1940-1944". Connecticut College.

- ^ a b Carre, Gilly (14 August 2014). Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands. Bloomsbury Academic (August 14, 2014). ISBN 978-1472509208.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Willmot, Louise (May 2002). "The Goodness of Strangers: Help to Escaped Russian Slave Labourers in Occupied Jersey, 1942–1945". Contemporary European History. 11 (2): 211–227. doi:10.1017/s0960777302002023. JSTOR 20081829. S2CID 159916806.

- ^ Willmot, Louise, (May 2002) The Goodness of Strangers: Help to Escaped Russian Slave Labourers in Occupied Jersey, 1942-1945," Contemporary European History, Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 214. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e f Sanders, Paul (2005). The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940–1945. Jersey: Jersey Heritage Trust / Société Jersiaise. ISBN 0953885836.

- ^ Tabb, A Peculiar Occupation, (Jersey 2005)

- ^ a b c Turner, Barry (April 2011). Outpost of Occupation: The Nazi Occupation of the Channel Islands, 1940-1945. Aurum Press (April 1, 2011). ISBN 978-1845136222.

- ^ McLaughlin, Roy (1997). The Sea was their Fortune. Seaflower Books 1997. ISBN 0948578866.

- ^ Parker, William (15 August 2011). Life in Occupied Guernsey: The Diaries of Ruth Ozanne 1940-45. Amberley Publishing Limited, 2013. ISBN 9781445612607.

- ^ The Organisation Todt and the Fortress Engineers in the Channel Islands. CIOS Archive book 8.

- ^ "The First Attack on England". Calvin.

- ^ a b Lempriére, Raoul (1974). History of the Channel Islands. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0709142522.

- ^ "German Occupation of the Channel Islands". BBC.

- ^ Rückzug (Retreat), Joachim Ludewig, Rombach GmbHm, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1991, Eng. trans. © 2012 The University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 978-0-8131-4079-7, pp. 37-41.

- ^ Falla, Frank (2018). The Silent War (4th ed.). Guernsey: Blue Ormer. OCLC 1053852898.

- ^ Edmund Blampied, Marguerite Syvret, London 1986 ISBN 0-906030-20-X

- ^ Cruickshank (1975)

- ^ Briggs, Asa (1995). The Channel Islands: Occupation & Liberation, 1940-1945. Trafalgar Square Publishing. ISBN 978-0713478228.

- ^ a b Charybdis Association (1 December 2010). "H.M.S. Charybdis: A Record of Her Loss and Commemoration". World War 2 at Sea. naval-history.net. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Local History: HMS Charybdis". BBC.co.uk. 7 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Strappini, Richard (2004). St Martin, Guernsey, Channel Islands, a parish history from 1204. p. 152.

- ^ "Pine Tree Web Home Page". www.pinetreeweb.com.

- ^ a b c Bell, William (1995). I beg to report. Bell (1995). ISBN 978-0-9520479-1-9.

- ^ a b c Cortvriend, V V. Isolated Island. Guernsey Star (1947).

- ^ "THE GOLDEN GUERNSEY". Guernsey Goat Society.

- ^ Strappini, Richard (2004). St Martin, Guernsey, Channel Islands, a parish history from 1204.

- ^ a b Senator is a driving force behind move for international recognition, Jersey Evening Post, 9 March 2010

- ^ "1940- 45 OCCUPATION OF GUERNSEY BY GERMAN FORCES". Guernsey Museum.

- ^ Bunting (1995); Maughan (1980)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Guernsey resistance to German occupation 'not recognised'". BBC. 3 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i King, Peter. The Channel Islands War. Robert Hale Ltd; First edition (Jun. 1991). ISBN 978-0709045120.

- ^ "Liberation of the Channel Islands in 1945" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Bunting, Madelaine (1995). The Model Occupation: the Channel Islands under German rule, 1940–1945. London: Harper Collins. p. 316. ISBN 0-00-255242-6.

- ^ "Liberation stamps revealed". ITV News. 29 April 2015.

- ^ "François Scornet". Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Il y a 70 ans disparaissait François Scornet". Le Télégramme. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ a b "John Nettles: 'Telling the truth about Channel Islands cost me my friends'". Express. 5 November 2012.

- ^ "From the testimony of Walter Henry Lainé". The Guardian. 18 November 2010.

- ^ Bell, William. Guernsey Occupied but never Conquered. The Studio Publishing Services (2002). ISBN 978-0-9520479-3-3.

- ^ "Obituary: Hubert Nicolle". Independent. 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Harrowing Tales Of Nazi Persecution Uncovered". Sky News. 31 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mière, Joe (2004). Never to be forgotten. Channel Island Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9542669-8-1.

- ^ "Can you solve the mystery of the islander whose bike ride led to Belsen?". Bailiwick Express. 10 April 2017.

Bibliography

edit- Bell, William M. (2005), "Guernsey Occupied But Never Conquered", The Studio Publishing Services, ISBN 978-0952047933

- Bunting, Madeleine (1995), The Model Occupation: the Channel Islands under German rule, 1940–1945, London: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-255242-6

- Carre, Gilly, Sanders, Paul, Willmot, Louise, (2014) Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands: German Occupation, 1940-45, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1472509208

- Cruickshank, Charles G. (1975), The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, The Guernsey Press, ISBN 0-902550-02-0

- Jackson, Jeffrey H. (2020), Paper Bullets: Two Artists Who Risked Their Lives to Defy the Nazis, Chapel Hill, NC: Workman Publishing ISBN 9781616209162

- Lewis, John (1983), "A Doctor's Occupation", New English Library Ltd; New edition (July 1, 1983), ISBN 978-0450056765

- Maughan, Reginald C. F. (1980), Jersey under the Jackboot, London: New English Library, ISBN 0-450-04714-8

- Mière, Joe (2004), "Never to Be Forgotten", Channel Island Publishing, ISBN 978-0954266981

- Nettles, John (2012, Jewels & Jackboots, Channel Island Publishing & Jersey War Tunnels, ISBN 978-1-905095-38-4

- Sanders, Paul (2005), The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940–1945 Jersey Heritage Trust / Société Jersiaise, ISBN 0953885836

- Tabb, Peter (2005), A peculiar occupation, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 0-7110-3113-4

- Turner, Barry 92011), Outpost of Occupation: The Nazi Occupation of the Channel Islands, 1940-1945, Aurum Press, ISBN 978-1845136222