The consolidation of the Cuban Revolution is a period in Cuban history typically defined as starting in the aftermath of the revolution in 1959 and ending in 1962, after the total political consolidation of Fidel Castro as the maximum leader of Cuba. The period encompasses early domestic reforms, human rights violations, and the ousting of various political groups.[1][2][3][4] This period of political consolidation climaxed with the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, which then cooled much of the international contestation that arose alongside Castro's bolstering of power.[5]

| Part of the Cold War | |

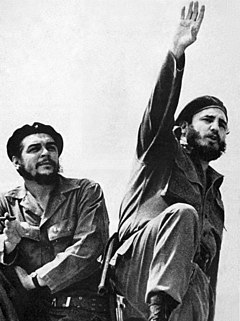

Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro (right) in 1961 | |

| Date | 1959–1962 |

|---|---|

| Location | Cuba |

| Outcome | Series of events including...

|

The political consolidation of Fidel Castro in the new Cuban government began in early 1959. It began with the appointment of communist officials to office and a wave of removals of other revolutionaries that criticized the appointment of communists. This trend came to a head with the Huber Matos affair and would continue that by mid-1960 little opposition remained to Castro within the government and few independent institutions existed in Cuba.[6][7]

As Castro's rule became more entrenched, between 1959 and 1960, Cuba's relationship with the United States began to falter. In the immediate aftermath of the 1959 revolution, Castro visited the United States to ask for aid and boast of land reform plans, which he believed the U.S. government would appreciate. Throughout 1960 tensions slowly escalated between Cuba and the United States due to the nationalizations of various American companies, retaliatory economic sanctions, and counterrevolutionary bombing raids. In January 1961, the U.S. cut off diplomatic relations with Cuba, and the Soviet Union started to solidify relations with Cuba. The U.S. feared growing Soviet influence in Cuba and backed the Bay of Pigs Invasion of April 1961, which later failed. By December 1961, Castro for the first time openly expressed his communist sympathies. Castro's fears of another invasion and his new Soviet allies influenced his decision to put nuclear missiles in Cuba, triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis.[8] In the aftermath of the crisis, the United States promised not to invade Cuba in the future; in compliance with this agreement, the U.S. withdrew all support from the Alzados, effectively crippling the resource-starved resistance.[9] The counterrevolutionary conflict, known abroad as the Escambray rebellion, lasted until about 1965, and has since been branded as the "Struggle Against Bandits" by the Cuban government.[9]

There are various historiographical interpretations of the political consolidation that occurred between 1959 and 1962. There is a periodization of these events, as the beginning of the "militarization of Cuba" which includes a long process of domestic militarization which climaxed in 1970.[10][11] There is the "grassroots dictatorship" model, which argues that the removal of liberal rights after the Cuban Revolution was the result of mass support and citizen deputization. This mass support came from a popular enthusiasm for national defense against American invasion.[12][13] There is also the "betrayal thesis" which posits that the political consolidation of Fidel Castro was a betrayal of the democratic aims of the Cuban Revolution against Batista.[14]

Background

editIdeology of the Cuban Revolution

editThe Cuba Revolution (Spanish: Revolución Cubana) was an armed revolt conducted by Fidel Castro and his fellow revolutionaries of the 26th of July Movement and its allies against the military dictatorship of Cuban President Fulgencio Batista. The revolution began in July 1953,[15] and continued sporadically until the rebels finally ousted Batista on 1 January 1959, replacing his government.[16]

The beliefs of Fidel Castro during the revolution have been the subject of much historical debate. Fidel Castro was openly ambiguous about his beliefs at the time. Some orthodox historians argue Castro was a communist from the beginning with a long-term plan; however, others have argued he had no strong ideological loyalties. Leslie Dewart has stated that there is no evidence to suggest Castro was ever a communist agent. Levine and Papasotiriou believe Castro believed in little outside of a distaste for American imperialism. While Ana Serra believed it was the publication of El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba.[17] As evidence for his lack of communist leanings they note his friendly relations with the United States shortly after the revolution and him not joining the Cuban Communist Party during the beginning of his land reforms.[18]

At the time of the revolution the 26th of July Movement involved people of various political persuasions, but most were in agreement and desired the reinstatement of the 1940 Constitution of Cuba and supported the ideals of Jose Marti. Che Guevara commented to Jorge Masetti in an interview during the revolution that "Fidel isn't a communist" also stating "politically you can define Fidel and his movement as 'revolutionary nationalist'. Of course he is anti-American, in the sense that Americans are anti-revolutionaries".[19]

Flight of Batista

editOn 31 December 1958, the Battle of Santa Clara took place in a scene of great confusion. The city of Santa Clara fell to the combined forces of Che Guevara, Cienfuegos, and Revolutionary Directorate (RD) rebels led by Comandantes Rolando Cubela, Juan ("El Mejicano") Abrahantes, and William Alexander Morgan. News of these defeats caused Batista to panic. He fled Cuba by air for the Dominican Republic just hours later on 1 January 1959. Comandante William Alexander Morgan, leading RD rebel forces, continued fighting as Batista departed and had captured the city of Cienfuegos by 2 January.[20]

Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo entered Havana's Presidential Palace, proclaimed the Supreme Court judge Carlos Piedra as the new president, and began appointing new members to Batista's old government.[21]

Castro learned of Batista's flight in the morning and immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, the military commander in the city, Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers not to fight, and Castro's forces took over the city. The forces of Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. They had met no opposition on their journey from Santa Clara to Cuba's capital. Castro himself arrived in Havana on 8 January after a long victory march. His initial choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.[22]

1959: "Year of Liberation"

editRebel victory

editCastro learned of Batista's flight in the morning of January 1 and immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, the military commander in the city, Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers not to fight, and Castro's forces took over the city. The forces of Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. They had met no opposition on their journey from Santa Clara to Cuba's capital. Castro himself arrived in Havana on 8 January after a long victory march. His initial choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, would later take office on 3 January.[23]

The new revolutionary government would name 1959 the "year of liberation", because of the year's efforts to deconstruct the old Batista government structures.[24]

Castro had made his opinion clear that lawyer Manuel Urrutia Lleó should become president, leading a provisional civilian government following Batista's fall. Politically moderate, Urrutia had defended MR-26-7 revolutionaries in court, arguing that the Moncada Barracks attack was legal according to the Cuban constitution. Castro believed Urrutia would make a good leader, being both established yet sympathetic to the revolution. With the leaders of the junta under arrest, Urrutia was proclaimed provisional president on 2 January 1959, Urrutia had been chosen because of his prestige and acceptability to both the moderate middle-class backers of the revolution and to the guerrilla forces who took part in the alliance formed in Caracas in 1958.[25] with Castro erroneously announcing he had been selected by "popular election"; most of Urrutia's cabinet were MR-26-7 members.[26] On January 8, 1959, Castro's army entered Havana. Proclaiming himself Representative of the Rebel Armed Forces of the Presidency, Castro – along with close aides and family members – set up home and office in the penthouse of the Havana Hilton Hotel, there meeting with journalists, foreign visitors and government ministers.[27]

On 11 January 1959 Ed Sullivan would interview Fidel Castro in Matanzas and broadcast it on The Ed Sullivan Show. In the interview Ed Sullivan refers to Castro and other rebels as "a wonderful group of revolutionary youngsters" and point out their admiration for Catholicism. Fidel Castro would deny the rebels affiliation with communism. Hours after the interview Fidel Castro would ride on captured tanks into the capital in Havana.[28]

Officially having no role in the provisional government, Castro exercised a great deal of influence, largely because of his popularity and control of the rebel army. Ensuring the government implemented policies to cut corruption and fight illiteracy, he did not initially force through any radical proposals. Attempting to rid Cuba's government of Batistanos, the Congress elected under Batista was abolished, and all those elected in the rigged elections of 1954 and 1958 were banned from politics. The government now ruling by decree, Castro pushed the president to issue a temporary ban on all political parties, but repeatedly stated that they would get around to organizing multiparty elections; this never occurred.[29] He began meeting members of the Popular Socialist Party, believing they had the intellectual capacity to form a socialist government, but repeatedly denied being a communist himself.[30]

Once in power, President Urrutia swiftly began a program of closing all brothels, gambling outlets and the national lottery, arguing that these had long been a corrupting influence on the state. The measures drew immediate resistance from the large associated workforce. The disapproving Castro, then commander of Cuba's new armed forces, intervened to request a stay of execution until alternative employment could be found.[31]

Tribunals and executions

editThe first major political crisis arose over what to do with the captured Batista officials who had perpetrated the worst of the repression.[32] During the rebellion against Batista's dictatorship, the general command of the rebel army, led by Fidel Castro, introduced into the territories under its control the 19th-century penal law commonly known as the Ley de la Sierra (Law of the Sierra).[33] This law included the death penalty for serious crimes, whether perpetrated by the Batista regime or by supporters of the revolution. In 1959 the revolutionary government extended its application to the whole of the republic and to those it considered war criminals, captured and tried after the revolution. According to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, this latter extension was supported by the majority of the population, and followed the same procedure as those in the Nuremberg trials held by the Allies after World War II.[34]

To implement a portion of this plan, Castro named Guevara commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison, for a five-month tenure (2 January through 12 June 1959).[35] Guevara was charged by the new government with purging the Batista army and consolidating victory by exacting "revolutionary justice" against those regarded as traitors, chivatos (informants) or war criminals.[36] As commander of La Cabaña, Guevara reviewed the appeals of those convicted during the revolutionary tribunal process.[37] The tribunals were conducted by 2–3 army officers, an assessor, and a respected local citizen.[38] On some occasions the penalty delivered by the tribunal was death by firing-squad.[39] Raúl Gómez Treto, senior legal advisor to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, has argued that the death penalty was justified in order to prevent citizens themselves from taking justice into their own hands, as had happened twenty years earlier in the anti-Machado rebellion.[40] Biographers note that in January 1959 the Cuban public was in a "lynching mood",[41] and point to a survey at the time showing 93% public approval for the tribunal process.[37] Moreover, a 22 January 1959, Universal Newsreel broadcast in the United States and narrated by Ed Herlihy featured Fidel Castro asking an estimated one million Cubans whether they approved of the executions, and being met with a roaring "¡Si!" (yes).[42]

Between 1,000[43] and 20,000 Cubans estimated to have been killed at the hands of Batista's collaborators,[44][45][46][47] and many of the accused war criminals sentenced to death accused of torture and physical atrocities,[37] the newly empowered government carried out executions, punctuated by cries from the crowds of "¡al paredón!" ([to the] wall!)[32] It is widely believed that those executed were guilty of the crimes of which they were accused, but that the trials did not follow due process.[48][49]

-

Execution of a suspected Batistiano spy (January 10, 1959)

-

Captain Alejandro García Olayón is executed by a rebel firing squad led by René Rodríguez Cruz (December 10, 1959).

-

Priests from Manzanillo give last sacraments to Ramón Llópiz Reytor before his execution by firing squad (January 30, 1959).

-

Firing squad about to execute Lieutenant Enrique Despaigne Noret during the San Juan Hill massacre (January 12, 1959).

-

Execution of Arístidez Díaz in Manzanillo in eastern Cuba, assisted by Father José Luis Sarragoitia Lazpica. Behind the bodies of others recently executed (January 12, 1959).

Reforms and electoral delay

editStarting in March 1959, Fidel Castro announced in a speech he would attempt to end racial discrimination in Cuban society. He detailed a plan to bring black and white Cubans together in shared schools and other institutions, via equal opportunity. In a later televised discussion Castro claimed his plans were mostly to improve economic conditions for black Cubans and that he is not encouraging total social integration. Social clubs were to be totally integrated, private beaches opened, and schools totally nationalized.

Private schools that once had majority white student bodies were now nationalized and faced an influx of new black and mulatto students. Social clubs were told to integrate as early as January 1959. White and black social clubs began to dissolve. Racism became branded as counterrevolutionary and critics of the government were often branded as racists.[50] Some white Cubans were fearful of integration, while some black Cubans were fearful of the closing of black social clubs and its effects on Afro-Cuban cultural life.[50]

On April 9, 1959, Fidel Castro announced a delay in elections, under the slogan "revolution first, elections later". The cause of the delay was a supposed focus on domestic reforms.[51][52][53][54][55]

Disagreements also arose in the new government concerning pay cuts, which were imposed on all public officials on Castro's demand. The disputed cuts included a reduction of the $100,000 a year presidential salary Urrutia had inherited from Batista.[56] By February, following the surprise resignation of Miró, Castro had assumed the role of prime minister; this strengthened his power and rendered Urrutia increasingly a figurehead president.[57] As Urrutia's participation in the legislative process declined, other unresolved disputes between the two leaders continued to fester. His belief in the restoration of elections was rejected by Castro, who felt that they would usher in a return to the old discredited system of corrupt parties and fraudulent balloting that had marked the Batista era.[58]

Urrutia was then accused by the Avance newspaper of buying a luxury villa, which was portrayed as a frivolous betrayal of the revolution and led to an outcry from the general public. He denied the allegation issuing a writ against the newspaper in response. The story further increased tensions between the various factions in the government, though Urrutia asserted publicly that he had "absolutely no disagreements" with Fidel Castro. Urrutia attempted to distance the Cuban government (including Castro) from the growing influence of the Communists within the administration, making a series of critical public comments against the latter group. Whilst Castro had not openly declared any affiliation with the Cuban communists, Urrutia had been a declared anti-Communist since they had refused to support the insurrection against Batista,[59] stating in an interview, "If the Cuban people had heeded those words, we would still have Batista with us ... and all those other war criminals who are now running away".[58]

Agrarian reform

editOn 15 April 1959, Castro began an 11-day visit to the United States, at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.[60] Fidel Castro made the visit in hopes of securing U.S. aid for Cuba. While there he openly spoke of plans to nationalize Cuban lands and at the United Nations he declared Cuba was neutral in the Cold War.[8] He said during his visit: "I know the world thinks of us, we are Communists, and of course I have said very clear that we are not Communists; very clear."[61]

In the summer of 1959, Fidel began nationalizing plantation lands owned by American investors as well as confiscating the property of foreign landowners. He also seized property previously held by wealthy Cubans who had fled.[62][63][64] He nationalized sugar production and oil refinement, over the objection of foreign investors who owned stakes in these commodities.[65][66]

On July 17, 1959, Conrado Bécquer, the sugar workers' leader demanded Urrutia's resignation. Castro himself resigned as Prime Minister of Cuba in protest, but later that day appeared on television to deliver a lengthy denouncement of Urrutia, claiming that Urrutia "complicated" government, and that his "fevered anti-Communism" was having a detrimental effect. Castro's sentiments received widespread support as organized crowds surrounded the presidential palace demanding Urrutia's resignation, which was duly received. On July 23, Castro resumed his position as premier and appointed Osvaldo Dorticós as the new president.[59]

In July 1959, army commando Huber Matos grew suspicious of the new government after the deposition of President Manuel Urrutia Lleó, and attempted to soon resign. On 26 July, Castro and Matos met at the Hilton Hotel in Havana, where, according to Matos, Castro told him: "Your resignation is not acceptable at this point. We still have too much work to do. I admit that Raúl [Castro] and Che [Guevara] are flirting with Marxism ... but you have the situation under control ... Forget about resigning ... But if in a while you believe the situation is not changing, you have the right to resign."[67] On October 20, 1959, a political scandal occurred when army commander Huber Matos resigned and accused Fidel Castro of "burying the revolution". Fifteen of Matos' officers resigned with him. Immediately after the resignation Fidel Castro critiqued Matos and accused him of disloyalty, then sent Camilo Cienfuegos to arrest Matos and his accompanying officers. Matos and the officers were taken to Havana and imprisoned in La Cabaña.[68] The scandal is noted for its occurrence alongside a greater trend of removals of Fidel Castro's former collaborators in the revolution. It marked a turning point where Fidel Castro was beginning to exert more personal control over the new government in Cuba. Matos' arresting officer and former collaborator of Fidel Castro: Camilo Cienfuegos, would soon die in a mysterious plane crash shortly after the incident.[6] Huber Matos, military chief of Camagüey province, had complained to Fidel Castro that communists were being allowed to occupy leadership positions in the revolutionary government and the army. Finding Castro unwilling to discuss his concerns, Matos sent a letter to Castro resigning his command. Castro denounced Matos and sent troops to occupy key positions in Camagüey, expecting incorrectly that Matos would lead a revolt, and named Cienfuegos to take command and to arrest Matos. Matos pleaded with Cienfuegos who was a close friend, to listen to his concerns, but Cienfuegos assured him it could be worked out and arrested Matos. Shortly after Hubert Matos' detention various other disillusioned economists would send in their resignations. Felipe Pazos would resign as head of the National Bank and be replaced within a month by Che Guevara. Cabinet members Manuel Ray and Faustino Perez also resigned.[69]

The United States was already suspicious of Fidel Castro after he enacted the Agrarian Reform Law banning foreigners from owning land and his appointment of communist Nuñez Jimenez as head of the reform program. U.S. President Eisenhower refused any aggressive action against Cuba knowing it would push Cuba towards an alliance with the Soviet Union in the Cold War.[8]

Emigration

editBy the middle of 1959 various new policies had affected Cuban life such as the redistribution of property, nationalization of religious and private schools, and the banning of racially exclusive social clubs. Those that began to leave the island were driven by them being negatively affected by new economic policies, their distaste with new national public schools, or anxiety over government supported racial integration.[70] Many middle class emigrants were often professionals that were tied to American companies that were nationalized.[71]

Many of the emigrants that would leave believed they would be returning soon to Cuba,[72] believing the U.S. would soon intervene and overthrow the Fidel Castro government.[73] Some of those exiled in the United States would organize a militant resistance to the Fidel Castro government.[71]

The flight of many skilled workers after the revolution caused a “brain drain.” This loss of trained professionals sparked a renovation of the Cuban education system to accommodate the education of new professionals to replace those that had emigrated.[74]

1960: "Year of Agrarian Reform"

editUS sanctions and internal repression

editJournalists and editors began to criticize Castro's left-ward turn, the pro-Castro printers' trade union began to harass and disrupt press actions. In January 1960, the government proclaimed that each newspaper need to publish a "coletilla": a clarification, by the printers' union at the end of every article that criticized the government. These "clarifications" signaled the start of press censorship in Castro's Cuba.[75]

As the United States began to grow colder in relations with Cuba, the Soviet Union began much warmer relations. In February Soviet Deputy Premier Anastas Mikoyan visited Havana which resulted in a major Cuban-Soviet trade agreement which gave Cuba Soviet oil in exchange for sugar.[76]

Cuba-United States relations were heavily strained after the explosion of a French vessel, the La Coubre, in Havana harbor in March 1960. The ship carried weapons purchased from Belgium, and the cause of the explosion was never determined, but Castro publicly insinuated that the U.S. government was guilty of sabotage, and wanted to use the explosion as the first stage of an invasion. He ended this speech with "¡Patria o Muerte!" ("Fatherland or Death"), a proclamation that he made much use of in ensuing years.[77][78]

There had already existed for months a popular desire for some form of urban-based civil defense against sabotage but the actual formation of such an institution came after the La Coubre explosion. The Committees for the Defense of the Revolution were formed.[79] Local CDR groups were tasked with keeping "vigilance against counter-revolutionary activity", keeping a detailed record of each neighborhood's inhabitants' spending habits, level of contact with foreigners, work and education history, and any "suspicious" behavior. Among the increasingly persecuted groups were homosexual men.[80]

In April the first shipment of 300,000 tons of Soviet oil arrived in Cuba. Oil refineries owned by United States companies refused to refine the oil so the Cuban government nationalized the refineries in June. In July the United States suspended the purchase of 700,000 tons of sugar from Cuba, four days later the Soviet Union announced they would buy one million tons of Cuban sugar. In August the United States announced a total economic embargo on Cuba and threatened other Latin American and European nations with reprisals if they did not do the same.[24]

Fidel Castro's visit to New York City

editFidel Castro made a trip to New York City starting September 18 to attend the United Nations General Assembly. While there, international tensions were much higher than during his 1959 trip and he was restricted to only staying on Manhattan island. Castro checked in to the Shelbourne Hotel then checked out a few hours later, complaining that the Shelbourne had asked for a $10,000 cash advance. Castro would then threaten the United Nations that he would camp in Central Park if he couldn't find lodging, eventually checking into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem. While there Castro would meet with various interviewers with African-American newspapers, and other notable people such as Malcolm X, Langston Hughes, Nikita Khrushchev, and Allen Ginsberg. During his stay various Castro supporters and opponents would crowd the outside of the hotel, often fighting. Various sensationalist stories came out about Castro at the time, rumors claimed his entourage were harboring prostitutes in the hotel and that Castro was originally kicked out of the Shelbourne for keeping live chickens in the room. By September 26 Castro would finally speak at the U.N. and would speak for over four hours in denouncing United States foreign policy. Two days later Castro would return to Cuba in a Soviet jet, after his jets were repossessed at the airport.[81]

On 13 October 1960, the US government then prohibited the majority of exports to Cuba – the exceptions being medicines and certain foodstuffs – marking the start of an economic embargo. In retaliation, the Cuban National Institute for Agrarian Reform took control of 383 private-run businesses on 14 October, and on 25 October a further 166 US companies operating in Cuba had their premises seized and nationalized, including Coca-Cola and Sears Roebuck.[82] On 16 December, the US then ended its import quota of Cuban sugar.[83]

1961: "Year of Education"

editBay of Pigs Invasion

editIn January 1961, Castro ordered Havana's U.S. Embassy to reduce its 300 staff, suspecting many to be spies. The U.S. responded by ending diplomatic relations, and increasing CIA funding for exiled dissidents; these militants began attacking ships trading with Cuba, and bombed factories, shops, and sugar mills.[84] Both Eisenhower and his successor John F. Kennedy supported a CIA plan to aid a dissident militia, the Democratic Revolutionary Front, to invade Cuba and overthrow Castro; the plan resulted in the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961. On 15 April, CIA-supplied B-26's bombed three Cuban military airfields; the U.S. announced that the perpetrators were defecting Cuban air force pilots, but Castro exposed these claims as false flag misinformation.[85] Fearing invasion, he ordered the arrest of between 20,000 and 100,000 suspected counter-revolutionaries,[86] publicly proclaiming that "What the imperialists cannot forgive us, is that we have made a Socialist revolution under their noses". This was his first announcement that the government was socialist.[86]

The CIA and Democratic Revolutionary Front had based a 1,400-strong army, Brigade 2506, in Nicaragua. At night, Brigade 2506 landed along Cuba's Bay of Pigs, and engaged in a firefight with a local revolutionary militia. Castro ordered Captain José Ramón Fernández to launch the counter-offensive, before taking personal control himself. After bombing the invader's ships and bringing in reinforcements, Castro forced the Brigade's surrender on 20 April.[87] He ordered the 1189 captured rebels to be interrogated by a panel of journalists on live television, personally taking over questioning on 25 April. 14 were put on trial for crimes allegedly committed before the revolution, while the others were returned to the U.S. in exchange for medicine and food valued at U.S. $25 million.[88]

The CIA contemplated the idea of staging the second coming of Christ to destabilize Cuba. However, they did not go through with the plan.[89]

The Cuban government also began to expropriate from mafia leaders and taking millions in cash. Before Meyer Lansky fled Cuba, he was said to be worth an estimated $20M ($163,685,121 in 2016, accounting for inflation). When he died in 1983, his family was shocked to find out that his estate was worth about $57,000. Before he died, Lansky said that Cuba "ruined" him.[90]

In August 1961, during an economic conference of the Organization of American States in Punta del Este, Uruguay, Che Guevara sent a note of "gratitude" to United States President John F. Kennedy through Richard N. Goodwin, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. It read "Thanks for Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs). Before the invasion, the revolution was shaky. Now it's stronger than ever."[91] In response to United States Treasury Secretary Douglas Dillon presenting the Alliance for Progress for ratification by the meeting, Guevara antagonistically attacked the United States' claim of being a "democracy", stating that such a system was not compatible with "financial oligarchy, discrimination against blacks, and outrages by the Ku Klux Klan".[92]

Literacy campaign and backlash

editIn April the country began a massive eight-month long effort to abolish illiteracy in Cuba.[93][94] It began in April 1961 and ended on December 22, 1961, successfully raising Cuba's literacy rate to nearly one-hundred percent.[95][94]

Supporters of the revolution who were too young or otherwise unable to participate in the downfall of Fulgencio Batista saw the campaign as an opportunity to contribute to the success of the new government and hoped to instill a revolutionary consciousness in their students.[74] Many of the instructional texts used during the Literacy Campaign focused on the history of the Revolution and had strong political messages, which made the movement a target of opposition.

Some parents who were fearful of their children being put under military supervision and made to leave their homes to teach, had their children leave Cuba through Operation Peter Pan.[96]

P.M. affair

editAfter a brief period of artistic optimism beginning in 1959, where exiled artists returned to Cuba, the banning of the film P.M., in 1960, triggered a slow wave of emigration of Cuban filmmakers, who grew more frustrated with growing censorship in Cuba. The banning of the film P.M. was not a lone act of censorship which caused pessimism among filmmakers, instead, the censorship of P.M. was viewed to exemplify a growing atmosphere of artistic overwatch.[97][98][99][100]

The debates that followed the banning of P.M., among film critics, caused the intervention of Fidel Castro, who met with the contesting writers and delivered his famed "Words to the Intellectuals" speech.[101]

In his June 1961, speech "Word to the Intellectuals", Castro stated:

This means that within the Revolution, everything goes; against the Revolution, nothing. Nothing against the Revolution, because the Revolution has its rights also, and the first right of the Revolution is the right to exist, and no one can stand against the right of the Revolution to be and to exist, No one can rightfully claim a right against the Revolution. Since it takes in the interests of the people and Signifies the interests of the entire nation.[102]

While Castro's proclamation was vague in defining to who was considered loyal to "the revolution", Castro also later defined in his speech, a need for the National Cultural Council to direct artistic affairs in Cuba, and for the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba to publish literary debate magazines.[103]

Night of the Three Ps

editThe Night of the Three Ps (Spanish: La Noche de las Tres Pes) occurred on October 11, 1961, in Havana which was a massive police raid targeting prostitutes, pimps, and "pájaros" (term coined in Cuba to refer to homosexuals).[104] Cuban poet Virgilio Piñera was arrested the morning after the raid but quickly released to avoid international scandal. The raid was the first moralist round up of the new Castro government and would be the beginning of various round-ups in Cuba of people considered undesirables. The raid took place at a time of heightened moral campaigns in Cuba demonizing homosexuality and other qualities considered uncompatible with the Cuban revolutionary "new man".[105][106] The raid of the Night of the Three Ps officially targeted prostitutes (Spanish: prostitutas), "pájaros", and pimps (Spanish: proxenetas). Scholars and observers have noted that the police raid making the Night of the Three Ps could be better understood as having taken place for longer than that one night. Carlos Franqui noted in his memoir that the real targets of the raid included homosexuals, intellectuals, artists, vagrants, voodoo practitioners, and anyone deemed suspicious.[107]

Marxist-Leninist turn

editAlthough the USSR was hesitant regarding Castro's embrace of socialism,[108] relations with the Soviets deepened. Castro sent Fidelito for a Moscow schooling and while the first Soviet technicians arrived in June[109] Castro was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.[110] On December 2, 1961, Castro proclaimed on national television that he was a Marxist-Leninist, stating:[111]

I am a Marxist-Leninist, and I shall be a Marxist-Leninist to the end of my life.

In Castro's Second Declaration of Havana he called on Latin America to rise up in revolution.[112] In response, the U.S. successfully pushed the Organization of American States to expel Cuba; the Soviets privately reprimanded Castro for recklessness, although he received praise from China.[113] Despite their ideological affinity with China, in the Sino-Soviet split, Cuba allied with the wealthier Soviets, who offered economic and military aid.[114]

1962: "Year of Planning"

editEscalante affair

editBy 1962, Cuba's economy was in steep decline, a result of poor economic management and low productivity coupled with the U.S. trade embargo. Food shortages led to rationing, resulting in protests in Cárdenas.[115] Security reports indicated that many Cubans associated austerity with the "Old Communists" of the PSP, while Castro considered a number of them – namely Aníbal Escalante and Blas Roca – unduly loyal to Moscow. In March 1962 Castro removed the most prominent "Old Communists" from office, labelling them "sectarian".[116] On a personal level, Castro was increasingly lonely, and his relations with Che Guevara became strained as the latter became increasingly anti-Soviet and pro-Chinese.[117]

On 26 March 1962, the IRO became the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC) which, in turn, became the modern Communist Party of Cuba on 3 October 1965, with Castro as First Secretary. Castro remained the ruler of Cuba, first as Prime Minister and, from 1976, as President, until his retirement on February 20, 2008.[118] His brother Raúl officially replaced him as president later that same month.[119]

Cuban Missile Crisis

editMilitarily weaker than NATO, Khrushchev wanted to install Soviet R-12 MRBM nuclear missiles on Cuba to even the power balance.[120] Although conflicted, Castro agreed, believing it would guarantee Cuba's safety and enhance the cause of socialism.[121] Undertaken in secrecy, only the Castro brothers, Guevara, Dorticós and security chief Ramiro Valdés knew the full plan.[122] Upon discovering it through aerial reconnaissance, in October the U.S. implemented an island-wide quarantine to search vessels headed to Cuba, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis. The U.S. saw the missiles as offensive, though Castro insisted they were defensive.[123] Castro urged Khrushchev to threaten a nuclear strike on the U.S. should Cuba be attacked, but Khrushchev was desperate to avoid nuclear war.[124] Castro was left out of the negotiations, in which Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for a U.S. commitment not to invade Cuba and an understanding that the U.S. would remove their MRBMs from Turkey and Italy.[125] Feeling betrayed by Khrushchev, Castro was furious and soon fell ill.[126] Proposing a five-point plan, Castro demanded that the U.S. end its embargo, cease supporting dissidents, stop violating Cuban air space and territorial waters and withdraw from Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Presenting these demands to U Thant, visiting Secretary-General of the United Nations, the U.S. ignored them, and in turn Castro refused to allow the U.N.'s inspection team into Cuba.[127]

Aftermath

editInternational relations

edit"The greatest threat presented by Castro's Cuba is as an example to other Latin American states which are beset by poverty, corruption, feudalism, and plutocratic exploitation ... his influence in Latin America might be overwhelming and irresistible if, with Soviet help, he could establish in Cuba a Communist utopia."

— Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964[128]

In February 1963, Castro received a personal letter from Khrushchev, inviting him to visit the USSR. Deeply touched, Castro arrived in April and stayed for five weeks. He visited 14 cities, addressed a Red Square rally and watched the May Day parade from the Kremlin, was awarded an honorary doctorate from Moscow State University and became the first foreigner to receive the Order of Lenin.[129][130] Castro returned to Cuba with new ideas; inspired by Soviet newspaper Pravda, he amalgamated Hoy and Revolución into a new daily, Granma,[131] and oversaw large investment into Cuban sport that resulted in an increased international sporting reputation.[132] The government agreed to temporarily permit emigration for anyone other than males aged between 15 and 26, thereby ridding the government of thousands of opponents.[133] In 1963, his mother died. This was the last time his private life was reported in Cuba's press.[134] In 1964, Castro returned to Moscow, officially to sign a new five-year sugar trade agreement, but also to discuss the ramifications of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[135]

Despite Soviet misgivings, Castro continued calling for global revolution and the funding militant leftists. He supported Che Guevara's "Andean project", an unsuccessful plan to set up a guerrilla movement in the highlands of Bolivia, Peru and Argentina, and allowed revolutionary groups from across the world, from the Viet Cong to the Black Panthers, to train in Cuba.[136][137] He considered western-dominated Africa ripe for revolution, and sent troops and medics to aid Ahmed Ben Bella's socialist regime in Algeria during the Sand War. He also allied with Alphonse Massemba-Débat's socialist government in Congo-Brazzaville. In 1965, Castro authorized Guevara to travel to Congo-Kinshasa to train revolutionaries against the western-backed government.[138][139] Castro was personally devastated when Guevara was subsequently killed by CIA-backed troops in Bolivia in October 1967 and publicly attributed it to Che's disregard for his own safety.[140][141] In 1966, Castro staged a Tri-Continental Conference of Africa, Asia and Latin America in Havana, further establishing himself as a significant player on the world stage.[142][143] From this conference, Castro created the Latin American Solidarity Organization (OLAS), which adopted the slogan of "The duty of a revolution is to make revolution", signifying that Havana's leadership of the Latin American revolutionary movement.[144]

Castro's increasing role on the world stage strained his relationship with the Soviets, now under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev. Asserting Cuba's independence, Castro refused to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, declaring it a Soviet-U.S. attempt to dominate the Third World.[145] In turn, Soviet-loyalist Aníbal Escalante began organizing a government network of opposition to Castro, though in January 1968, he and his supporters were arrested for passing state secrets to Moscow.[146] Castro ultimately relented to Brezhnev's pressure to be obedient, and in August 1968 denounced the Prague Spring as led by a "fascist reactionary rabble" and praised the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[147][148][149]

One-party state

editIn October 1965, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations was officially renamed the "Cuban Communist Party" and published the membership of its Central Committee.[133] In 1965, Cuba was officially a one-party state after a long period of political solidification by Fidel Castro after the Cuban Revolution. In September 1966, Fidel Castro gave a speech to representatives of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. In the speech, he gave his ruling that workers would no longer receive material bonuses for extra labor and instead be encouraged by "moral enthusiasm" alone, which distanced Cuba from the Soviet model of using material incentives. This independent approach to economic policy fell into a global trend during the Cold War in which Third World countries adopted independent economic strategies in relation to the industrialized dominant power blocs.[150]

Cuba had begun what was referred to as the "radical experiment", where the country was to be reorganized to promote revolutionary consciousness and an independent economy. Rural to urban migration was regulated, excess urban workers were sent to the countryside, and agricultural labor became common for students, soldiers, and convicts. The Military Units to Aid Production were established and used "anti-social" prisoners as penal laborers in agriculture.[151]

In February 1968, a group in the Communist Party of Cuba and other official organizations known as the "microfaction" was completely purged from the government. The group numbered almost forty officials who endorsed Soviet-style material incentives over moral enthusiasm to encourage workers. They were accused of conspiring against the state, and made to serve prison sentences.[152] Influenced by China's Great Leap Forward, in 1968 Castro proclaimed a Great Revolutionary Offensive, closed all remaining privately owned shops and businesses and denounced their owners as capitalist counter-revolutionaries.[153]

Further emigration

editOn 28 September 1965, Fidel Castro announced that Cubans wishing to emigrate could do so beginning 10 October from the Cuban port of Camarioca. The administration of U.S. President Johnson tried to control the numbers it would admit to the U.S. and set some parameters for their qualifications, preferring those claiming political persecution and those with family members in the U.S. In negotiations with the Cuban government it set a target of 3,000 to 4,000 people to be transported by air. Despite those diplomatic discussions, Cuban Americans brought small leisure boats from the United States to Camarioca. In the resulting Camarioca boatlift, about 160 boats transported about 5,000 refugees to Key West for immigration processing by U.S. officials. The Johnson administration made only modest efforts to enforce restrictions on this boat traffic. Castro closed the port with little notice on 15 November, stranding thousands. On 6 November, the Cuban and U.S. governments agreed on the details on an emigration airlift based on family reunification and without reference to those the U.S. characterized as political prisoners and whom the Cubans termed counter-revolutionaries. To deal with the crowds at Camarioca, the U.S. added a maritime component to the airborne evacuation. Both forms of transport started operating on 1 December.[154][155]

From December 1965 to early 1973, under the Johnson and Nixon administrations, twice daily "Freedom Flights" (Vuelos de la Libertad) transported émigrés from Varadero Beach to Miami. The longest airlift of political refugees,[citation needed] it transported 265,297 Cubans to the United States with the help of religious and volunteer agencies. Flights were limited to immediate relatives and Cubans already in the United States with a waiting period anywhere from one to two years.[156]

Many who came through Camarioca and the Freedom Flights were much more racially diverse, of lower economic standing, and of more women compared to earlier emigration waves. This is mainly due to Castro's restriction not allowing skilled laborers to leave the country.[157]

Historiography

editIn the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Revolution and Fidel Castro's consolidation of power, a historical interpretation developed, known as the "betrayal thesis". This thesis heralded the original struggle against Batista, and considered the revolution's democratic aims to be endearing, but Castro's rise to power is considered a "betrayal" of the original revolution. This thesis was propagated by Cuban exile organizations such as the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front, and the Cuban Revolutionary Council.[158] The thesis was also famously propagated by anti-Stalinist historian Theodore Draper.[14]

The period of political consolidation between 1959 and 1962, has also been considered the beginning of the "militarization of Cuba", which lasted from 1959 to 1970, and climaxed with the Revolutionary Offensive, that was organized by the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.[10] A chief proponent of the "militarization" periodization is historian Irving Louis Horowitz, who argues the militant origins of the revolution, the popularity of militarism in Latin America, Cuba's single-crop economy, desires to resist U.S. hostility, military support of regimes abroad, and Cuba's role as the USSR's lone ally in the Americas caused the militarization of Cuba. [159]

Another historiographical interpretation is that the political system that developed during the political consolidation of 1959–1962, was a "grassroots dictatorship". This label was developed by historian Lillian Guerra, and is used to describe how citizens themselves participated in the removal of liberal rights, and the mass deputization of citizens by the government, to act as citizen spies in the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution.[12]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Hellinger, Daniel (2014). Comparative Politics of Latin America Democracy at Last?. Taylor and Francis. p. 289. ISBN 9781134070077.

- ^ Staten, Clifford (2005). The History of Cuba. St. Martin's Press. pp. 69–105. ISBN 9781403962591.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Whalen, Charles (1975). Cuba Study Mission A Fact-finding Survey, June 26 – July 2, 1975. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 3.

- ^ Henken, Ted; Celaya, Miriam; Castellanos, Dimas (2013). Cuba. ABC-CLIO. p. 93. ISBN 9781610690126.

- ^ Lawson, George (2013). Anatomies of Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9781108587808.

- ^ a b Beyond the Eagle's Shadow New Histories of Latin America's Cold War. University of New Mexico Press. 2013. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0826353696.

- ^ Moore, Robin (2006). Music and Revolution Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba. University of California Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0520247116.

- ^ a b c Stanley, John. "What impact did the Cuban Revolution have on the Cold War?" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Cuba: Intelligence and the Bay of Pigs". Stanford University. 26 September 2002. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ a b Cuba's Forgotten Decade How the 1970s Shaped the Revolution. Lexington Books. 2018. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9781498568746.

- ^ Horowitz, Irving Louis (January 1995). Cuban Communism/8th Editi. Transaction Publisher. p. 585. ISBN 9781412820899.

- ^ a b Dictators and Autocrats Securing Power Across Global Politics. Taylor & Francis. 2021. p. (Section 4). ISBN 9781000467604.

- ^ Tarrago, Rafael (2017). Understanding Cuba as a Nation From European Settlement to Global Revolutionary Mission. Taylor & Francis. p. 99. ISBN 9781315444475.

- ^ a b Welch, Richard (October 2017). Response to Revolution The United States and the Cuban Revolution, 1959-1961. University of North Carolina Press. p. 141. ISBN 9781469610467.

- ^ Faria, Jr., Miguel A. (27 July 2004). "Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement". Newsmax Media. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Cuba Marks 50 Years Since 'Triumphant Revolution'" Archived 27 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Jason Beaubien. NPR. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Serra, Ana. Ideology and the novel in the Cuban revolution: the making of a revolutionary identity in the first decade. OCLC 42657417.

- ^ "Cuba receives first US shipment in 50 years" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (24 April 2017). Cuba's Revolutionary World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674978324.

- ^ Faria (2002), p. 69

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 212; Coltman 2003, p. 137.

- ^ Thomas (1998), pp. 691–93

- ^ Thomas (1998), pp. 691–693

- ^ a b Nieto, Clara (2011). Masters of War Latin America and U.S. Aggression From the Cuban Revolution Through the Clinton Years. Seven Stories Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1609800499.

- ^ Debra Evenson (June 4, 2019). Revolution In The Balance Law And Society In Contemporary Cuba. Taylor & Francis. p. 29. ISBN 9781000310054. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 153, 161; Quirk 1993, p. 216; Coltman 2003, pp. 126, 141–142.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 164; Coltman 2003, p. 144.

- ^ "When Fidel Castro Charmed the United States". Smithsonian.com.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 171–172; Quirk 1993, pp. 217, 222; Coltman 2003, pp. 150–154.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 166, 170; Quirk 1993, p. 251; Coltman 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Robert E. Quirk. Fidel Castro. p229.

- ^ a b Skidmore 2008, pp. 273

- ^ Gómez Treto 1991, p. 115 "The Penal Law of the War of Independence (July 28, 1896) was reinforced by Rule 1 of the Penal Regulations of the Rebel Army, approved in the Sierra Maestra February 21, 1958, and published in the army's official bulletin (Ley penal de Cuba en armas, 1959)" (Gómez Treto 1991, p. 123).

- ^ Gómez Treto 1991, pp. 115–116

- ^ Anderson 1997, pp. 372, 425

- ^ Anderson 1997, p. 376

- ^ a b c Taibo 1999, p. 267

- ^ Kellner 1989, p. 52

- ^ Niess 2007, p. 60

- ^ Gómez Treto 1991, p. 116

- ^ Anderson 1997, p. 388

- ^ Rally For Castro: One Million Roar "Si" To Cuba Executions – Video Clip by Universal-International News, narrated by Ed Herlihy, from 22 January 1959

- ^ Wickham-Crowley, Timothy P. (1990). Exploring Revolution: Essays on Latin American Insurgency and Revolutionary Theory. Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-87332-705-3.

- ^ Conflict, Order, and Peace in the Americas, by the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, 1978, p. 121. "The US-supported Batista regime killed 20,000 Cubans"

- ^ The World Guide 1997/98: A View from the South, by University of Texas, 1997, ISBN 1-869847-43-1, pg 209. "Batista engineered yet another coup, establishing a dictatorial regime, which was responsible for the death of 20,000 Cubans."

- ^ Fidel: The Untold Story. (2001). Directed by Estela Bravo. First Run Features. (91 min). Viewable clip. "An estimated 20,000 people were murdered by government forces during the Batista dictatorship."

- ^ Niess 2007, p. 61

- ^ Chase, Michelle (2010). "The Trials". In Greg Grandin; Joseph Gilbert (eds.). A Century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 163–98. ISBN 978-0822347378. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ Castañeda 1998, pp. 143–144

- ^ a b Benson, Devyn (2012). "Owning the Revolution: Race, Revolution, and Politics from Havana to Miami, 1959–1963" (PDF).

- ^ Wright, Thomas (2022). Democracy in Latin America A History Since Independence. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 9781538149355.

- ^ Martinez-Fernandez, Luis (2014). Revolutionary Cuba A History. University Press of Flordia. p. 52. ISBN 9780813048765.

- ^ Dominguez, Jorge (2009). Cuba Order and Revolution. Harvard University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780674034280.

- ^ The Department of State Bulletin. Michigan State University. 1960. p. 322.

- ^ Buckman, Robert (2013). Latin America 2013. Stryker Post. p. 147. ISBN 9781475804812.

- ^ Richard Gott. Cuba. A new history. p170.

- ^ Anderson, John Lee (1997). Che Guevara : A revolutionary life. Random House. pp. 376–405.

- ^ a b Quirk, Robert E. (1993). "The Political End of President Urrutia – Fidel Castro". Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ a b Thomas, Hugh (1998). Cuba. The pursuit for freedom. pp. 830–832.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (15 April 2013). "Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Cuban Revolution". 1959 Year in Review. United Press International. 1959. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Gibson, William E. (5 April 2015). "Cuban exiles seek compensation for seized property". Sun-Sentinel.com. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Luscombe, Joe Lamar Richard (1 August 2015). "Cuban exiles hope diplomatic thaw can help them regain confiscated property". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Run from Cuba, Americans cling to claims for seized property". Tampa Bay Times. 29 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Cuba, you owe us $7 billion". Boston Globe. 18 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ "1960 Dollars in 2016 Dollars". Inflation Calculator. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ "American Experience: Fidel Castro. People and Events: Huber Matos, a Moderate in the Cuban Revolution". PBS. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Anderson, John Lee (2010). Che Guevara A Revolutionary Life (Revised ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 427. ISBN 978-0802197252.

- ^ Gonzalez, Servando (2002). The Nuclear Deception Nikita Khrushchev and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Spooks Books. p. 52. ISBN 9780971139152.

- ^ Benson, Devyn Spence (22 March 2019). Not blacks, but citizens!: racial politics in revolutionary Cuba, 1959-1961 (Thesis). The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill University Libraries. doi:10.17615/ys7q-8n14. S2CID 161971505.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Irving; Suchlicki, Jaime (2001). Cuban Communism. Transaction Publishers. pp. 413–417. ISBN 9781412820875.

- ^ Duany, Jorge (1999). "Cuban communities in the United States: migration waves, settlement patterns and socioeconomic diversity". Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe Revue du Centre de Recherche Sur les Pouvoirs Locaux dans la Caraïbe (11): 69–103. doi:10.4000/plc.464. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ Pedraza, Silvia (Winter 1998). "Cuba's Revolution and Exodus". Journal of the International Institute. 5 (2). hdl:2027/spo.4750978.0005.204.

- ^ a b Klein, Deborah (2004). "Education as Social Revolution". Independent School. 63 (3): 38–47.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 197.

- ^ Fauriol, Georges (1990). Cuba The International Dimension. Transaction Publishers. pp. 42–45. ISBN 1412820820.

- ^ George, Alice (2013). The Cuban Missile Crisis The Threshold of Nuclear War. Taylor and Francis. p. 17. ISBN 978-1136174049.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Fagen, Richard (1969). The Transformation of Political Culture in Cuba. Stanford University: Stanford University Press. pp. 70. ISBN 9780804707022.

- ^ Young, Allen (1982). Gays under the Cuban revolution. Grey Fox Press. ISBN 0-912516-61-5.

- ^ Andrews, Evan (August 31, 2018). "Fidel Castro's Wild New York Visit". History.com.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 214.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 215.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 217–220.

- ^ a b Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 222–225.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Bevins, Vincent (2020). The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1541742406.

- ^ "Fidel Castro a mixed legacy that includes fighting the mafia". 26 November 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Anderson 1997, p. 509

- ^ "Economics Cannot be Separated from Politics" speech by Che Guevara to the ministerial meeting of the Inter-American Economic and Social Council (CIES), in Punta del Este, Uruguay on 8 August 1961.

- ^ Perez, Louis A. Cuba Between Reform and Revolution. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. Print.

- ^ a b "Literacy Campaigns | Concise Encyclopedia of Latin American Literature – Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ^ Uriarte, Miren. Cuba: Social Policy at the Crossroads: Maintaining Priorities, Transforming Practice. An Oxfam America Report. 2002, pp. 6–12. <http://www.oxfamamerica.org/newsandpublications/publications/research_reports/art3670.html Archived 2009-03-03 at the Wayback Machine>, December 2004.

- ^ "OPERATION PEDRO PAN AND THE EXODUS OF CUBA'S CHILDREN". upf.com. University Press of Florida.

- ^ Women Screenwriters An International Guide. Palgrave Macmillan. 2015. p. "Cuba" section. ISBN 9781137312372.

- ^ Diddon, Joan (2017). Miami. Open Road. p. Section 12. ISBN 9781504045681.

- ^ Jorge Berenschot, Denis (2005). Performing Cuba (Re)writing Gender Identity and Exile Across Genres. P. Lang. p. 111. ISBN 9780820474403.

- ^ Revolutionary Change in Cuba. University of Pittsburgh Press. 1972. p. 458. ISBN 9780822974130.

- ^ Censorship A World Encyclopedia. Taylor and Francis. 2001. pp. 400–401. ISBN 9781136798641.

- ^ Castro, Fidel (1961). "CASTRO'S SPEECH TO INTELLECTUALS ON 30 JUNE 61". lanic.utexas.edu.

- ^ Story, Isabel (4 December 2019). Soviet Influence on Cuban Culture, 1961–1987 When the Soviets Came to Stay. Lexington Books. p. 69. ISBN 9781498580120.

- ^ Zayas, Manuel (20 January 2006). "Mapa de la homofobia". CubaInformación (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ The Whole Island Six Decades of Cuban Poetry. University of California Press. 2009. p. 566. ISBN 9780520258945.

- ^ Anderson, Thomas (2006). Everything in Its Place The Life and Works of Virgilio Piñera. Bucknell University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780838756355.

- ^ Hynson, Rachel (2020). Laboring for the State Women, Family, and Work in Revolutionary Cuba, 1959–1971. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–202. ISBN 9781107188679.

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 231, Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 405.

- ^ "Fidel Castro speaks on Marxism-Leninism: Dec. 2, 1961". ucf.digital.flvc.org. University of Central Florida.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 230–234, Quirk 1993, pp. 395, 400–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 232–234, Quirk 1993, pp. 397–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 232, Quirk 1993, p. 397.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233, Quirk 1993, pp. 203–204, 410–412, Coltman 2003, p. 189.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 234–236, Quirk 1993, pp. 403–406, Coltman 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 258–259, Coltman 2003, pp. 191–192.

- ^ "Fidel Castro Resigns as Cuba's President". New York Times. 20 February 2008. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Raúl Castro becomes Cuban president". New York Times. 24 February 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 238–239, Quirk 1993, p. 425, Coltman 2003, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 239, Quirk 1993, pp. 443–434, Coltman 2003, pp. 199–200, 203.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 241–242, Quirk 1993, pp. 444–445.

- ^ "Cuba Once More", by Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964, p. 23.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 245–248

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 249

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 249–250

- ^ a b Coltman 2003, p. 213

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 250–251

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 263

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 255

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 211

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 255–256, 260

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 211–212

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 267–268

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 216

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 265

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 214

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 267

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 269

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 269–270

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 270–271

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 216–217

- ^ Castro, Fidel (August 1968). "Castro comments on Czechoslovakia crisis". FBIS.

- ^ Mesa-Lago, Carmelo (1972). Revolutionary Change in Cuba. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9780822974130.

- ^ Henken, Ted (2008). Cuba A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 139. ISBN 9781851099849.

- ^ Mesa-Lago, Carmelo (1972). "Ideological, Political, and Economic Factors in the Cuban Controversy on Material Versus Moral Incentives". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 14 (1): 71. doi:10.2307/174981. JSTOR 174981.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 227

- ^ Engstrom, David Wells (1997). Presidential Decision Making Adrift: The Carter Administration and the Mariel Boatlift. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 24ff. ISBN 9780847684144. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Cuban Americans", by Thomas D. Boswell, in Ethnicity in Contemporary America: A Geographical Appraisal, Jesse O. McKee, ed. (Rowman & Littlefield, 2000) pp144-145

- ^ "Search the Freedom Flights database - The Cuban Revolution". MiamiHerald.com. 30 July 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Powell, John (2005). "Cuban immigration". Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. Facts on File. pp. 68–71. ISBN 9781438110127. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Bustamante, Michael (2021). Cuban Memory Wars Retrospective Politics in Revolution and Exile. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 74–80. ISBN 9781469662046.

- ^ The Democratic Imagination Dialogues on the Work of Irving Louis Horowitz. Transaction Publishers. 2015. ISBN 9781412856263.

Cited sources

edit- Bourne, Peter G. (1986). Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 978-0-396-08518-8.

- Castañeda, Jorge G. (1998). Compañero : the life and death of Che Guevara (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75940-9.

- Coltman, Leycester (2003). The Real Fidel Castro. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10760-9.

- Faria, Miguel A. Jr (2002). Cuba in Revolution: Escape from a Lost Paradise. Milledgeville, GA: Hacienda Pub Inc. ISBN 0-9641077-3-2.

- Gómez Treto, Raul (1991). "Thirty Years of Cuban Revolutionary Penal Law". Latin American Perspectives. 18 (2): 114–125. doi:10.1177/0094582X9101800211. ISSN 0094-582X. JSTOR 2633612. S2CID 144092152.

- Kellner, Douglas (1989). Ernesto "Che" Guevara (World Leaders Past & Present). Chelsea House Publishers (Library Binding edition). ISBN 1-55546-835-7.

- Lazo, Mario (1970). American Policy Failures in Cuba – Dagger in the Heart. New York: Twin Circle Publishing Co. pp. 198–200, 204. LCCN 68-31632.

- Niess, Frank (2007). Guevara. London: Haus. ISBN 978-1-904341-99-4.

- Taibo II, Paco Ignacio (1999). Guevara, Also Known as Che. St Martin's Griffin. 2nd edition. ISBN 0-312-20652-6.

- Skidmore, Thomas E.; Smith, Peter H. (2008). Modern Latin America. Oxford University Press. p. 436. ISBN 978-0-19-505533-7.