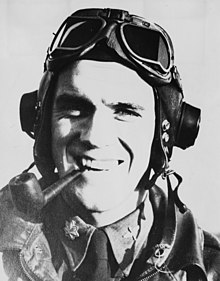

Richard Allen Peterson (February 26, 1923 – June 4, 2000) was a fighter ace and a major in the United States Army Air Forces. During World War II, he was the fourth highest scoring ace of 357th Fighter Group, with 15.5 aerial victories.[1][2][3]

Richard Allen Peterson | |

|---|---|

Major Richard A Peterson of the 357th Fighter Group | |

| Nickname(s) | Pete, Bud |

| Born | February 26, 1923 Hancock, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | June 4, 2000 (aged 77) Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Buried | Lakewood Cemetery Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Army Air Forces |

| Years of service | 1942–1946 |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | 364th Fighter Squadron, 357th Fighter Group |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | Silver Star Distinguished Flying Cross (3) Air Medal (13) |

Early life and education

editPeterson was born in Hancock, Minnesota and grew up in Alexandria, Minnesota. He graduated from Alexandria High School in 1940 and then attended the University of Minnesota.[1][4][5] From 1940 to 1941, he was part of the university's track team.[6]

World War II

editOn 30 March 1942, he enlisted in the Aviation Cadet Program of the United States Army Air Forces and in June 1942, he left the university to become an aviation cadet.[7]

After finishing flight training in March 1943, Peterson was assigned to the 364th Fighter Squadron of the 357th Fighter Group at Tonopah, Nevada, flying Bell P-39 Airacobras. On October 4, 1943, while flying a P-39 during a transfer flight from El Paso, Texas to Tucson, Arizona, he became disoriented and got separated from his flight. Despite suffering from navigation issues, Peterson made a deadstick landing at El Chapo town in Chihuahua, Mexico, resulting in his aircraft being damaged beyond repair and some railcars also being damaged due to the P-39's landing. Mexican officials confisciated the P-39's ammunition despite an USAAF officer showing up at the crash site upon Peterson's request. Peterson was later allowed to travel back to Nevada to rejoin his fighter group.[8][9]

In November 1943, the 357th Fighter Group was assigned to European Theater of Operations and was stationed at RAF Leiston in England, where the unit was now equipped with the North American P-51 Mustangs. On March 6, 1944, he shot down a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 over Bordeaux, France, his first aerial victory. On March 16, he was credited with the shared destruction of a twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110 and on March 18, he shot down a Messerschmitt Bf 109 over Augsburg, Germany, his second aerial victory. By the end of May 1944, he shot eight more enemy aircraft including two shared destructions, bringing his total aerial victories to nine and earned the title of flying ace. On July 1, he shot down two Bf 109s south of Saint-Quentin, France and later on the same month, he returned to the United States for shore leave.[10][11]

In October 1944, he returned to the 357th FG and on October 6, he shot down a Fw 190 over Berlin, Germany and on October 7, he shot down a Bf 109 over Jena, Germany. On November 2, he shot down a Bf 109 north of Merseburg, Germany. His fifteenth and final aerial victory was on November 11, when he shot down a Bf 109 over an airfield in Neuhausen, Germany.[12][11]

Peterson had 15.5 air victories and destroyed 3.5 aircraft on the ground while flying 150 missions.[13] His P-51 Mustang aircraft were named Hurry Home Honey after his wife's letter closing.[2] On one of the missions, he witnessed a Bf 109 shooting at American B-17 bomber crews in parachutes after being shot down. Peterson attacked the Bf 109 and forced the German pilot to bail out of the aircraft. He shot and killed him as he descended on his parachute. Peterson recalled that some of his unit were nervous that this would invite a retaliatory response from the Luftwaffe. "But they had to be there to know what I was seeing," Peterson said. "Those guys were helpless, the bomber crews going down".[14][15][16]

Post war

editPeterson and his wife Elaine had three children and numerous grandchildren.[6] After World War II, he left military service in 1946, and returned to the University of Minnesota and obtained a degree in architecture in 1949 which became his career. In 2000, he was inducted into the Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame.[17][18][19][1]

He died of cancer on June 4, 2000, at the age of 77 and was buried at Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis.[6][1]

Aerial victory credits

edit| Chronicle of aerial victories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | # | Type | Location | Aircraft flown | Unit Assigned |

| March 6, 1944 | 1 | Focke-Wulf Fw 190 | Bordeaux, France | P-51B Mustang | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| March 16, 1944 | 0.5 | Messerschmitt Bf 110 | Ulm, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| March 18, 1944 | 1 | Messerschmitt Bf 109 | Augsburg, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| April 11, 1944 | 1 | Bf 109 | Magdeburg, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| April 24, 1944 | 1 | Bf 109 | Munich, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| April 30, 1944 | 2 | Fw 190 | Auxerre, France | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| May 12, 1944 | 0.5 | Fw 190 | Frankfurt, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| May 13, 1944 | 1.5 | Messerschmitt Me 410 | Grünberg, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| May 28, 1944 | 1 | Bf 109 | Magdeburg, Germany | P-51B | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| July 1, 1944 | 2 | Bf 109 | Saint-Quentin, France | P-51D Mustang | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| October 6, 1944 | 1 | Fw 190 | Berlin, Germany | P-51D | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| October 7, 1944 | 1 | Bf 109 | Jena, Germany | P-51D | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| November 2, 1944 | 1 | Fw 190 | Merseburg, Germany | P-51D | 364 FS, 357 FG |

| November 11, 1944 | 1 | Bf 109 | Neuhausen, Germany | P-51D | 364 FS, 357 FG |

- SOURCES: Air Force Historical Study 85: USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World War II

Awards and decorations

edit| Army Air Forces Pilot Badge |

| Silver Star | |

| Distinguished Flying Cross with two bronze oak leaf clusters | |

| Air Medal with two silver and two bronze oak leaf clusters | |

| American Campaign Medal | |

| European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with silver campaign star | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| Croix de Guerre with bronze star (France) |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d William Hess. America's Top Eighth Air Force Aces in Their Own Words. Zenith Imprint. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-1-61060-702-5.

- ^ a b Chris Bucholtz (20 December 2012). Mustang Aces of the 357th Fighter Group. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-78200-872-9.

- ^ Martin W. Bowman (2006). Echoes of England: The 8th Air Force in World War Two. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3738-5.

- ^ "Richard Peterson - Recipient -". valor.militarytimes.com. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ "Richard A. (Bud) Peterson". Alexandria Education Foundation. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ a b c "Obituary: Richard A. Peterson (Aged 77)". Star Tribune (Newspapers.com). 2000-06-07. Retrieved 2024-07-14.

- ^ "Access to Archival Databases (AAD)". National Archives. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- ^ Olmsted, Merle C. "See Them Tumbling Down". To Fly and Fight. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Flories, Santiago A. (2019). Mexicans at War: Mexican Military Aviation in the Second World War, 1941–1945. Helion Limited. ISBN 9781913118396. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ "Air Force Historical Study 85: USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World War II" (PDF). 1978. p. 150. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Richard Peterson (Victory Table)". To Fly and Fight. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Peterson, Richard. "Combat Report (6 October 1944)". WWII Aircraft Performance. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Jerry Scutts (20 November 2012). Mustang Aces of the Eighth Air Force. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-1-78200-675-6.

- ^ Jay A. Stout (2004). Fighter Group: The 352nd "Blue-Nosed Bastards" in World War II. Stackpole Books. pp. 126–127.

- ^ TJ3 History (2021-10-01). "The P-51 Mustang Pilot that Killed a German in his Parachute - Brutal True Story of Richard Peterson". YouTube. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "WWII vet Richard Peterson explains why you don't Shoot a Parachuting Soldier". YouTube. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Richard A. "Bud" Peterson - - Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame Inductee". Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ "Elaine B. Peterson". Star Tribune. 2015-08-16. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ "Richard A. (Bud) Peterson". Alexandria Education Foundation. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

External links

edit- "Richard A. "Bud" Peterson 1923 - 2000". Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- "Richard A Peterson". American Air Museum in Britain. Retrieved 2018-06-27.