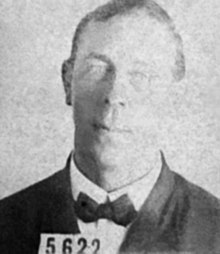

Robert Hichens (16 September 1882 – 23 September 1940) was a British sailor who was part of the deck crew on board the RMS Titanic when she sank on her maiden voyage on 15 April 1912. He was one of seven quartermasters on board the vessel and was at the ship's wheel when the Titanic struck the iceberg. He was in charge of Lifeboat #6, where he refused to return to rescue people from the water due to fear of the boat being sucked into the ocean with the huge suction created by the Titanic, or swamped by other floating passengers. According to several accounts of those on the boat, including Margaret Brown, who argued with him throughout the early morning, Lifeboat 6 did not return to save other passengers from the waters. In 1906, he married Florence Mortimore in Devon, England; when he registered for duty aboard the Titanic, his listed address was in Southampton, where he lived with his wife and two children.

Robert Hichens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16 September 1882 |

| Died | 23 September 1940 (aged 58) Aberdeen, Scotland |

| Resting place | Trinity Cemetery, Aberdeen, Scotland |

| Known for | Crew Member of the RMS Titanic |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | British Merchant Navy |

| Years of service | 1914–1918 1939–1940 |

| Battles / wars | |

Titanic

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Hichens gained notoriety after the disaster because of his conduct in Lifeboat No. 6, of which he was in command. Passengers accused him of refusing to go back to rescue people from the water after the ship sank, that he called the people in the water "stiffs," and that he constantly criticised those at the oars while he was manning the rudder. Hichens was later to testify at the United States Senate inquiry that he had never used the words "stiffs" and that he had other words to describe bodies. He would also testify to have been given direct orders by second mate Charles Lightoller and Captain Edward Smith to row to where a light could be seen (a steamer they thought) on the port bow, drop off the passengers and return. Later, it was alleged that he complained that the lifeboat was going to drift for days before any rescue came. At least two Lifeboat No. 6 passengers publicly accused Hichens of being drunk: Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen and Mrs Lucian Philip Smith.[1]

When the RMS Carpathia came to rescue Titanic's survivors, he said that the ship was not there to rescue them, but to pick up the bodies of the dead. By this time, the other people in the lifeboat had lost patience with Hichens. Although Hichens protested, Denver millionaire Margaret "Molly" Brown told the others to start rowing to keep warm. After a last attempt by Hichens to keep control of the lifeboat, Brown threatened to throw him overboard. These events would later end up being depicted in the Broadway musical and film, The Unsinkable Molly Brown. During the US inquiry into the disaster, Hichens denied the accounts by the passengers and crew in Lifeboat No. 6. He had been initially concerned about the suction from the Titanic and later by the fact that being a mile away from the wreck, with no compass and in complete darkness, they had no way of returning to the stricken vessel.[citation needed]

Later life

editHichens served with the Army Service Corps during the First World War; by 1919, he was third officer on a small ship named Magpie. Then Hichens moved to Devon, sometime in the 1920s, where he purchased a motorboat from a man named Harry Henley and operated a boat charter. In 1931, his wife and children left him and moved to Southampton. Over the next two years, Hichens traveled the country looking for work, and it is believed that he took to heavy drinking. In 1933, Hichens was jailed for attempting to murder Henley and was released in 1937.[2]

Death

editOn 23 September 1940, at age 58, Hichens died of heart failure aboard the ship English Trader, while the vessel was moored off the coast of Aberdeen in the north-east of Scotland.[3] His body was buried in Section 10, Lair 244, of Trinity Cemetery in Aberdeen.[4]

Depicted in fiction

editHichens' conduct was featured in the 1997 blockbuster, Titanic, in which he was played by Paul Brightwell. He was depicted as a tall thin man with a cockney accent, when in fact he was 5' 6", had a stocky build and spoke with a pronounced Cornish accent. He was also depicted saying "if you don't shut that hole in your face" to Molly Brown, but in fact those words were spoken by a steward in lifeboat 8.[citation needed] Unused footage from the film Titanic, that featured Brightwell as Hitchens, was also used in Cameron's documentary film Ghosts of the Abyss, wherein he was portrayed refusing an order to return to the sinking Titanic, stating "It's our lives now, not theirs".

Hichens' conduct was also depicted in the 1996 miniseries Titanic, in which he was played by Martin Evans. Hichens is shown telling the survivors in his lifeboat to "pipe down" when they get excited about spotting a flare from a ship on the horizon. He strongly protests when Molly Brown starts encouraging the other women to row towards the light, and she threatens to throw Hichens overboard. This depiction is more accurate than in the 1997 blockbuster.

Hichens was portrayed by Arthur Gross, who was uncredited, in the 1958 film A Night to Remember, which also portrays his conflict with Molly Brown in a more accurate manner.

Hichens' negative attitude was further depicted in Diane Hoh's 1998 romance novel Titanic: The Long Night, which recounts his conduct as well as that of Molly Brown, from the viewpoint of Elizabeth Farr, a fictional lifeboat passenger. Molly Brown urged lifeboat passengers to start rowing to keep warm, and Hichens protested, declaring that he was commanding the lifeboat, and he made a move to stop her. "I will throw you overboard if you interfere," she told him in this account.

In September 2010, Hichens' name was brought back into the limelight by Louise Patten, granddaughter of the most senior officer to have survived the Titanic disaster, second officer Charles Lightoller. In press interviews leading up to the publication of her latest novel, Good as Gold (into which she has worked the story of the catastrophe), Patten reports that a "straightforward" steering error by Hichens, brought about by his misunderstanding of a tiller order, caused the Titanic to hit an iceberg in 1912.[5][6] Patten's allegation that Hichens caused the disaster by turning the ship's wheel the wrong way is not supported by testimony at both the British and US enquiries, which established that the second watch officer, Sixth Officer James Moody, was stationed behind Hichens, supervising his actions, and he had confirmed to First Officer William Murdoch that the order had been carried out correctly.[7][8][9]

The claim was also disputed by Hichens' great-granddaughter on Channel 4 News. Sally Nilsson explained that Hichens was a well-trained Quartermaster with years of experience steering large vessels. He had been responsible on his watch for steering the Titanic for four days before the collision and would not have made such a glaring error. As to the steering orders, in 1912 they were as follows: There was only one way of giving steering orders. The order was always given with reference to the tiller. To go to port the Officer ordered starboard. The Quartermaster turned the wheel to port, tiller went to starboard and the ship turned to port. This was a hangover from the old days when ships were steered with tillers, steering oars, etc. The change in steering orders did not occur until the 1930s. Sally Nilsson's biography on the life of Robert Hichens was published in 2011.[10]

Hichens also appears in the play Iceberg – Right Ahead! by Chris Burgess, which debuted on 22 March 2012 at Upstairs at the Gatehouse. In this production, he was played by Liam Mulvey.

Portrayals

edit- Arthur Gross (1958), A Night to Remember (British film)

- Martin Evans (1996), Titanic

- Paul Brightwell (1997), Titanic

- Miguel Wilkins (2003), Ghosts of the Abyss; documentary

References

edit- ^ "Robert Hichens, Quartermaster". www.williammurdoch.net. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Three Men on the Titanic". The Maritime Executive. 15 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Spignesi, Stephen J (2011). "Surviving the Sinking of the Titanic". The Titanic for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-118-17766-2.

He died of heart failure possibly resulting from stomach cancer or a gastric ulcer in 1940 aboard the ship English Trader off the Coast of Aberdeen, Scotland, at the age of 58. It was thought he was buried at sea until his grave was discovered in Aberdeen, Scotland in 2012 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-17551053.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Gall, Charlie (6 April 2012). "Grave of seaman who 'sank the Titanic' is discovered in Aberdeen". Daily Record. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Mike Collett-White (reporter), Paul Casciato (editor) (22 September 2010). "Titanic sunk by steering mistake, author says". Daily Telegraph. Reuters. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Family's Titanic secret revealed". BBC News Northern Ireland. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Maltin, Tim; Aston, Eloise (2010). 101 Things You Thought You Knew About the Titanic...But Didn't London: Beautiful Books. ISBN 1-905636-68-7, page 89

- ^ "Testimony of Robert Hichens (Quartermaster, SS Titanic)". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ United States Senate Enquiry: Testimony of Alfred Olliver

- ^ Nillsson, Sally (2011). The Man Who Sank Titanic: The Troubled Life of Quartermaster Robert Hichens. Stroud, England: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6071-0.