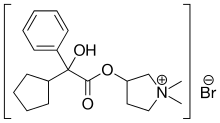

Glycopyrronium bromide is a medication of the muscarinic anticholinergic group.[7] It does not cross the blood–brain barrier and consequently has few to no central effects. It is given by mouth,[8] via intravenous injection, on the skin,[9] and via inhalation.[4][5][6] It is a synthetic quaternary ammonium compound.[2] The cation, which is the active moiety, is called glycopyrronium (INN)[10] or glycopyrrolate (USAN).

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Robinul, Cuvposa, Seebri, others |

| Other names | glycopyrrolate (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a602014 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, inhalation, topical, injection, subcutaneous |

| Drug class | Antimuscarinic (peripherally-selective) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 0.6–1.2 hours |

| Excretion | 85% Kidney, unknown amount in the bile |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.990 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H28BrNO3 |

| Molar mass | 398.341 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| |

| |

| | |

The most common side effects include irritability, flushing, nasal congestion, reduced secretions in the airways, dry mouth, constipation, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, and urinary retention.[7]

In September 2012, glycopyrronium was approved for medical use in the European Union.[4] In June 2018, glycopyrronium was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat excessive underarm sweating, becoming the first drug developed specifically to reduce excessive sweating.[11] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12]

Medical uses

editGlycopyrronium was first used in 1961 to treat peptic ulcers. Since 1975, intravenous glycopyrronium has been used before surgery to reduce salivary, tracheobronchial, and pharyngeal secretions.[13] It is also used in conjunction with neostigmine, a neuromuscular blocking reversal agent, to prevent neostigmine's muscarinic effects such as bradycardia.[14] It can be administered to raise the heart rate in reflex bradycardia as a result of a vasovagal reaction, which often will also increase the blood pressure.[15]

It is also used to reduce excessive saliva (sialorrhea),[7][16][17][18] and to treat Ménière's disease.[19]

It has been used topically and orally to treat hyperhidrosis, in particular, gustatory hyperhidrosis.[20][21]

When inhaled, it is used to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[4][5][6] Doses for inhalation are much lower than oral ones, so that swallowing a dose will not have an effect.[22][23]

Side effects

editDry mouth, urinary retention, headaches, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and blurry vision are possible side effects of the medication.[13]

Pharmacology

editMechanism of action

editGlycopyrronium competitively blocks muscarinic receptors,[13][24] thus inhibiting cholinergic transmission.

Pharmacokinetics

editGlycopyrronium bromide affects the gastrointestinal tracts, liver and kidney but has a very limited effect on the brain and the central nervous system. In horse studies, after a single intravenous infusion, the observed tendencies of glycopyrronium followed a tri-exponential equation, by rapid disappearance from the blood followed by a prolonged terminal phase. Excretion was mainly in urine and in the form of an unchanged drug. Glycopyrronium has a relatively slow diffusion rate, and in a standard comparison to atropine, is more resistant to penetration through the blood-brain barrier and placenta.[25]

Research

editReferences

edit- ^ "Neurological therapies". Health Canada. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Robinul- glycopyrrolate tablet Robinul Forte- glycopyrrolate tablet". DailyMed. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Dartisla ODT- glycopyrrolate orally disintegrating tablets tablet, orally disintegrating". DailyMed. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Seebri Breezhaler EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ a b c "Tovanor Breezhaler EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ a b c "Enurev Breezhaler EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Sialanar EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2023. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Glycopyrrolate Oral Inhalation". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Glycopyrronium Topical". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Bajaj V, Langtry JA (July 2007). "Use of oral glycopyrronium bromide in hyperhidrosis". The British Journal of Dermatology. 157 (1): 118–121. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07884.x. PMID 17459043. S2CID 29080876.

- ^ "FDA OKs first drug made to reduce excessive sweating". AP News. Archived from the original on 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ a b c Chabicovsky M, Winkler S, Soeberdt M, Kilic A, Masur C, Abels C (May 2019). "Pharmacology, toxicology and clinical safety of glycopyrrolate". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 370: 154–169. Bibcode:2019ToxAP.370..154C. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2019.03.016. PMID 30905688. S2CID 85498396.

- ^ Howard J, Wigley J, Rosen G, D'mello J (February 2017). "Glycopyrrolate: It's time to review". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 36: 51–53. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.09.013. PMID 28183573.

- ^ Gallanosa A, Stevens JB, Quick J (June 2023). "Glycopyrrolate". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252291. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Mier RJ, Bachrach SJ, Lakin RC, Barker T, Childs J, Moran M (December 2000). "Treatment of sialorrhea with glycopyrrolate: A double-blind, dose-ranging study". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 154 (12): 1214–1218. doi:10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1214. PMID 11115305. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ^ Tscheng DZ (November 2002). "Sialorrhea - therapeutic drug options". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (11): 1785–1790. doi:10.1345/aph.1C019. PMID 12398577. S2CID 45799443.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Olsen AK, Sjøgren P (October 1999). "Oral glycopyrrolate alleviates drooling in a patient with tongue cancer". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 18 (4): 300–302. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00080-9. PMID 10534970.

- ^ Maria SA, Claudia C, Pamela G, Andrea C, Roberto A (1 December 2012). "Medical therapy in Ménière's disease". Audiological Medicine. 10 (4): 171–177. doi:10.3109/1651386X.2012.718413. S2CID 72380413.

- ^ Kim WO, Kil HK, Yoon DM, Cho MJ (August 2003). "Treatment of compensatory gustatory hyperhidrosis with topical glycopyrrolate". Yonsei Medical Journal. 44 (4): 579–582. doi:10.3349/ymj.2003.44.4.579. PMID 12950111.

- ^ Kim WO, Kil HK, Yoon KB, Yoon DM (May 2008). "Topical glycopyrrolate for patients with facial hyperhidrosis". The British Journal of Dermatology. 158 (5): 1094–1097. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08476.x. PMID 18294315. S2CID 39870296.

- ^ "EPAR – Product information for Seebri Breezhaler" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 28 September 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Tzelepis G, Komanapolli S, Tyler D, Vega D, Fulambarker A (January 1996). "Comparison of nebulized glycopyrrolate and metaproterenol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". The European Respiratory Journal. 9 (1): 100–103. doi:10.1183/09031936.96.09010100. PMID 8834341.

- ^ Haddad EB, Patel H, Keeling JE, Yacoub MH, Barnes PJ, Belvisi MG (May 1999). "Pharmacological characterization of the muscarinic receptor antagonist, glycopyrrolate, in human and guinea-pig airways". British Journal of Pharmacology. 127 (2): 413–420. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702573. PMC 1566042. PMID 10385241.

- ^ Rumpler MJ, Colahan P, Sams RA (June 2014). "The pharmacokinetics of glycopyrrolate in Standardbred horses". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 37 (3): 260–268. doi:10.1111/jvp.12085. PMID 24325462.

- ^ Hansel TT, Neighbour H, Erin EM, Tan AJ, Tennant RC, Maus JG, et al. (October 2005). "Glycopyrrolate causes prolonged bronchoprotection and bronchodilatation in patients with asthma". Chest. 128 (4): 1974–1979. doi:10.1378/chest.128.4.1974. PMID 16236844. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- ^ Gilman MJ, Meyer L, Carter J, Slovis C (November 1990). "Comparison of aerosolized glycopyrrolate and metaproterenol in acute asthma". Chest. 98 (5): 1095–1098. doi:10.1378/chest.98.5.1095. PMID 2225951. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.