Roger Keith "Syd" Barrett (6 January 1946 – 7 July 2006) was an English singer, guitarist and songwriter who co-founded the rock band Pink Floyd in 1965. Until his departure in 1968, he was Pink Floyd's frontman and primary songwriter, known for his whimsical style of psychedelia,[1] English-accented singing, and stream-of-consciousness writing style.[4] As a guitarist, he was influential for his free-form playing and for employing effects such as dissonance, distortion, echo and feedback.

Syd Barrett | |

|---|---|

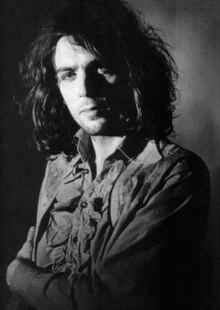

Barrett in 1969 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Roger Keith Barrett |

| Born | 6 January 1946 Cambridge, England |

| Died | 7 July 2006 (aged 60) Cambridge, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1963–1974 |

| Labels | Harvest |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | sydbarrett |

Trained as a painter, Barrett was musically active for fewer than ten years. With Pink Floyd, he recorded the first four singles, their debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), portions of their second album A Saucerful of Secrets (1968), and several songs that were not released until years later. In April 1968, Barrett was ousted from the band amid speculation of mental illness and his use of psychedelic drugs. He began a brief solo career in 1969 with the single "Octopus", followed by albums The Madcap Laughs (1970) and Barrett (1970), recorded with the aid of members of Pink Floyd.[5]

In 1972, Barrett left the music industry, retired from public life and guarded his privacy until his death. He continued painting and dedicated himself to gardening. Pink Floyd recorded several tributes and homages to him, including the 1975 song suite "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" and parts of the 1979 rock opera The Wall. In 1988, EMI released an album of unreleased tracks and outtakes, Opel, with Barrett's approval. In 1996, Barrett was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Pink Floyd. He died of pancreatic cancer in 2006.

Early life

Roger Keith Barrett was born on 6 January 1946[6] in Cambridge to a middle-class family living at 60 Glisson Road.[7][8] He was the fourth of five children.[9] His father, Arthur Max Barrett, was a prominent pathologist[7][10][11] and was said to be related to Elizabeth Garrett Anderson through Max's maternal grandmother Ellen Garrett.[10][11] In 1951, his family moved to 183 Hills Road, Cambridge.[7][8]

Barrett played piano occasionally but usually preferred writing and drawing. He bought a ukulele aged 10, a banjo at 11[12] and a Höfner acoustic guitar at 14.[13][14] A year after he purchased his first acoustic guitar, he bought his first electric guitar and built his own amplifier.[citation needed] He was a Scout with the 7th Cambridge troop and went on to be a patrol leader.[9]

Barrett reportedly used the nickname Syd from the age of 14, derived from the name of an old Cambridge jazz bassist,[14][15] Sid "the Beat" Barrett; Barrett changed the spelling to differentiate himself.[16] By another account, when Barrett was 13, his schoolmates nicknamed him Syd after he came to a field day at Abington Scout site wearing a flat cap instead of his scout beret, because "Syd" was a "working-class" name.[17] He used both names interchangeably for several years. His sister Rosemary said: "He was never Syd at home. He would never have allowed it."[15]

At one point at Morley Memorial Junior School, Barrett was taught by the mother of his future Pink Floyd bandmate Roger Waters.[18] Later, in 1957, he attended Cambridgeshire High School for Boys[19] with Waters.[7] His father died of cancer on 11 December 1961,[14][20] less than a month before Barrett's 16th birthday.[21] On this date, Barrett left the entry in his diary blank.[14] By this time, his siblings had left home and his mother rented out rooms to lodgers.[20][22][23]

Eager to help her son recover from his grief, Barrett's mother encouraged the band in which he played, Geoff Mott and the Mottoes, a band which Barrett formed,[14] to perform in their front room. Waters and Barrett were childhood friends, and Waters often visited such gigs.[7][14][24] At one point, Waters organised a gig, a CND benefit at Friends Meeting House on 11 March 1962,[7] but shortly afterwards Geoff Mott joined the Boston Crabs, and the Mottoes broke up.[14]

In September 1962, Barrett took a place at the art department of the Cambridgeshire College of Arts and Technology,[25] where he met the future Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour.[26] In late 1962 and early 1963, the Beatles made an impact on Barrett, and he began to play Beatles songs at parties and at picnics. In 1963, he became a Rolling Stones fan and, with then-girlfriend Libby Gausden, saw them perform at a village hall in Cambridgeshire.[26] He would cite Jimmy Reed as an influence; however, he remarked that Bo Diddley was his greatest influence.[27]

At this point, Barrett started writing songs. One friend recalled hearing "Effervescing Elephant", which he later recorded for his solo album Barrett.[28] Also around this time, Barrett and Gilmour occasionally played acoustic gigs together.[29] Barrett referred to Gilmour as "Fred" in letters to girlfriends and relatives.[30] Barrett had played bass guitar with Those Without in mid-1963[29][31] and bass and guitar with the Hollerin' Blues the next year.[29] In 1964, Barrett and Gausden saw Bob Dylan perform.[26] After this performance, Barrett was inspired to write "Bob Dylan Blues".[32] Barrett, now thinking about his future,[29] decided to apply for Camberwell College of Arts in London.[33] He enrolled in the college in mid-1964 to study painting.[29][34]

Career

Pink Floyd (1965–1968)

Starting in 1964, the band that would become Pink Floyd evolved through various line-up and name changes including the Abdabs,[35][36] the Screaming Abdabs,[36] Sigma 6[36][37] and the Meggadeaths.[36] In 1965, when Barrett joined them they were known as the Tea Set[36][38] (sometimes spelled T-Set).[39] When they played with another band of the same name, Barrett came up with the name the Pink Floyd Sound (also known as the Pink Floyd Blues Band,[39] later the Pink Floyd).[nb 1]

In 1965, Barrett had his first LSD trip in the garden of his friend Dave Gale,[43][44] with Ian Moore and the future Pink Floyd cover artist Storm Thorgerson.[nb 2][43] During one trip, Barrett and another friend, Paul Charrier, ended up naked in the bath, reciting: "No rules, no rules".[45] As a result of the continued drug use, the band became absorbed in Sant Mat, a Sikh sect. Thorgerson (then living on Earlham Street) and Barrett went to a London hotel to meet the sect's guru. Thorgerson joined the sect, but Barrett was deemed too young. Thorgerson saw this as a deeply important event in Barrett's life, as he was upset by the rejection. While living near his friends, Barrett wrote more songs, including "Bike".[42]

London underground, Blackhill Enterprises and gigs

While Pink Floyd began by playing cover versions of American R&B songs,[46] by 1966 they had carved out their own style of improvised rock and roll,[47][48] which drew as much from improvised jazz.[49] After the guitarist Bob Klose departed, the band's direction changed. However, the change was not instantaneous,[nb 3] with more improvising on the guitars and keyboards.[42] The drummer, Nick Mason, said most of the band's ideas came from Barrett.[nb 4][42]

Around this time, Barrett wrote most of the songs for Pink Floyd's first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), and songs that later appeared on his solo albums.[52] His reading reputedly included Grimm's Fairy Tales, Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and The I-Ching.[52] In 1966, Pink Floyd became a popular group in the London underground psychedelic music scene.[13] By the end of the year, Pink Floyd had gained a reliable management team in Andrew King and Peter Jenner.[54] In October, they booked a session at Thompson Private Recording Studio,[55] in Hemel Hempstead, for Pink Floyd to record demos.[nb 5][56] King said of the demos: "That was the first time I realised they were going to write all their own material, Syd just turned into a songwriter, it seemed like overnight."[57]

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

In 1967, Pink Floyd signed a record deal with EMI.[58] They recorded their first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, intermittently between February and July 1967 in Studio 3 at Abbey Road Studios (then called EMI Recording Studios), and produced by the former Beatles engineer Norman Smith.[59] Of the eleven songs Barrett wrote eight and co-wrote another two.[60] The album reached number six on the British album charts.[61]

Health problems

Through late 1967 and early 1968, Barrett became increasingly erratic, partly as a consequence of his heavy use of psychedelic drugs such as LSD.[13] Once described as joyful, friendly, and extroverted, he became increasingly depressed, withdrawn, and began experiencing hallucinations, disorganised speech, memory lapses, intense mood swings and periods of catatonia.[9] Although the changes began gradually, according to several friends —including the Pink Floyd keyboardist Richard Wright— he went missing for a long weekend and returned "a completely different person".[9]

One of the striking features of his change was the development of a blank, dead-eyed stare. Barrett did not recognise friends, and he often did not know where he was. While Pink Floyd were recording "See Emily Play" at the Sound Techniques studio, Gilmour stopped by on his return visit from Europe to say hello to Barrett. According to Gilmour, he "just looked straight through me, barely acknowledged me that I was there".[62] Record producer Joe Boyd encountered Barrett and the rest of the Floyd at the UFO Club in mid-1967, which he described in his memoir: "I had exchanged pleasantries with the first three when Syd emerged from the crush. His sparkling eyes had always been his most attractive feature but that night they were vacant, as if someone had reached inside his head and turned off a switch. During their set he hardly sang, standing motionless for long passages, arms by his sides, staring into space."[63] On a tour of Los Angeles, Barrett is said to have exclaimed, "Gee, it sure is nice to be in Las Vegas!"[9] Many reports described him on stage, strumming one chord through the entire concert, or not playing at all.[64] At a show in Santa Monica, Barrett slowly detuned his guitar.[65]

Interviewed on the Pat Boone in Hollywood television programme during the tour, Barrett replied with a "blank and totally mute stare". According to Mason, "Syd wasn't into moving his lips that day." Barrett exhibited similar behaviour during the band's first appearance on Dick Clark's television show American Bandstand.[66] Surviving footage of this appearance shows Barrett miming his parts competently;[67] however, during a group interview afterwards, Barrett gave terse answers. During their appearance on the Perry Como show, Wright had to mime all the vocals on "Matilda Mother" because of Barrett's condition.[68] Barrett would often forget to bring his guitar to sessions, damage equipment and was occasionally unable to hold the plectrum.[69] Before a performance in late 1967, Barrett reportedly crushed Mandrax tranquilliser tablets and a tube of Brylcreem into his hair, which melted down his face under the heat of the stage lighting,[70] making him look like "a guttered candle".[71] Mason disputed the Mandrax portion of this story, saying that "Syd would never waste good mandies".[72] During Pink Floyd's UK tour with Jimi Hendrix in November, the guitarist David O'List of the Nice, who were fifth on the bill,[73] substituted for Barrett on several occasions when he was unable to perform or failed to appear.[74]

Departure from Pink Floyd

Around Christmas 1967, Pink Floyd asked Gilmour to join as a second guitarist to cover for Barrett. For a handful of shows, Gilmour played and sang while Barrett wandered around on stage, occasionally joining the performance. The other band members grew tired of Barrett's behaviour. On 26 January 1968, when Waters was driving on the way to a show at Southampton University, they elected not to pick him up. One person said, "Shall we pick Syd up?" and another said, "Let's not bother."[75][76][77][78] As Barrett had written the bulk of the band's material, the plan was to retain him as a non-touring member, as the Beach Boys had done with Brian Wilson, but this proved impractical.[77][79][80]

According to Waters, Barrett came to what was to be their last practice session with a new song he had dubbed "Have You Got It Yet?". The song seemed simple when he first presented it, but it soon became impossible to learn. The band eventually realised that Barrett was changing the arrangement as they played,[77][80] and that Barrett was playing a joke on them.[81] According to Gilmour, "Some parts of his brain were perfectly intact—his sense of humour being one of them."[82] Waters called it "a real act of mad genius".[77][80]

Of the songs Barrett wrote for Pink Floyd after The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, only "Jugband Blues" was included on their second album, A Saucerful of Secrets (1968). "Apples and Oranges" became an unsuccessful single, while "Scream Thy Last Scream", "Vegetable Man" and the instrumental "In the Beechwoods" remained unreleased until 2016.[9] Another instrumental, mislabelled "Sunshine" by bootleggers, remains unreleased. Barrett played guitar on the Saucerful of Secrets tracks "Remember a Day" and "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun".[83]

Feeling guilty, the members of Pink Floyd did not tell Barrett that he was no longer in the band. According to Wright, who lived with Barrett at the time, he told Barrett he was going out to buy cigarettes when leaving to play a show. He would return hours later to find Barrett in the same position, sometimes with a cigarette burned completely down between his fingers. Emerging from catatonia and unaware that a long period had elapsed, Barrett would ask, "Have you got the cigarettes?" The incident was referenced in the 1982 film Pink Floyd – The Wall.[9]

Barrett spent time outside the recording studio, in the reception area,[84] waiting to be invited in. He also came to a few performances and glared at Gilmour.[83] On 6 April 1968, Pink Floyd announced that Barrett was no longer a member,[84] the same day their contract with Blackhill Enterprises was terminated. Considering him the band's musical leader, Blackhill Enterprises retained Barrett.[9][77][85]

Solo years (1968–1972)

After leaving Pink Floyd, Barrett was out of the public eye for a year.[86] In 1969, at the behest of EMI and Harvest Records, he embarked on a brief solo career, releasing two solo albums, The Madcap Laughs and Barrett (both 1970), and a single, "Octopus". Some songs, "Terrapin", "Maisie" and "Bob Dylan Blues", reflected Barrett's early interest in the blues.[87]

The Madcap Laughs (1970)

After Barrett left Pink Floyd, Jenner quit as their manager. He led Barrett into EMI Studios to record tracks[88] in May that were released on Barrett's first solo album, The Madcap Laughs. However, Jenner said: "I had seriously underestimated the difficulties of working with him."[89] By the sessions of June and July, most of the tracks were in better shape; however, shortly after the July sessions, Barrett broke up with his girlfriend Lindsay Corner and went on a drive around Britain, ending up in psychiatric care in Cambridge.[90] During New Year 1969, Barrett—somewhat recovered—had taken up tenancy in a flat on Egerton Gardens, South Kensington, London, with the postmodernist artist Duggie Fields.[90][91] Barrett's flat was so close to Gilmour's that Gilmour could look right into Barrett's kitchen.[90]

Deciding to return to music, Barrett contacted EMI and was passed to Malcolm Jones, the head of EMI's new prog rock label, Harvest.[88] After Norman Smith[92] and Jenner declined to produce Barrett's record,[92] Jones produced it.[90][92] Barrett wanted to recover the recordings made with Jenner; several of the tracks were improved upon.[93] The sessions with Jones started in April 1969 at EMI Studios. After the first, Barrett brought in friends to help: the Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley, and Willie Wilson, the drummer of Gilmour's old band Jokers Wild. For the sessions, Gilmour played bass. Jones said that communicating with Barrett was difficult: "It was a case of following him, not playing with him. They were seeing and then playing so they were always a note behind."[90] A few tracks on the album feature overdubs by members of Soft Machine.[94] During this time, Barrett also played guitar on the sessions for the Soft Machine founder Kevin Ayers' debut LP Joy of a Toy,[95] although his performance on "Religious Experience", later titled "Singing a Song in the Morning", was not released until the album was reissued in 2003.[94][96]

At one point, Barrett told his flatmate that he was going for an afternoon drive, but followed Pink Floyd to Ibiza; according to legend, he skipped check-ins and customs, ran onto the runway and attempted to flag down a jet. One of his friends, J. Ryan Eaves, the bass player for the short-lived but influential Manchester band York's Ensemble, spotted him on a beach wearing dirty clothes and with a carrier bag full of money. During the trip, Barrett asked Gilmour for help in the recording sessions.[90]

After two of the Gilmour/Waters-produced sessions,[97] they remade one track from the Soft Machine overdubs and recorded three tracks. These sessions came to a minor halt when Gilmour and Waters were mixing Pink Floyd's newly recorded album, Ummagumma. However, through the end of July, they managed to record three more tracks. The problem with the recording was that the songs were recorded as Barrett played them "live" in studio. On the released versions a number of them have false starts and commentaries from Barrett.[90] Despite the track being closer to complete and better produced, Gilmour and Waters left the Jones-produced track "Opel" off Madcap.[98]

Gilmour later said of the sessions for The Madcap Laughs:

[The sessions] were pretty tortuous and very rushed. We had very little time, particularly with The Madcap Laughs. Syd was very difficult, we got that very frustrated feeling: Look, it's your fucking career, mate. Why don't you get your finger out and do something? The guy was in trouble, and was a close friend for many years before then, so it really was the least one could do.[99]

Upon the album's release in January 1970, Jones was shocked by the substandard musicianship on the songs produced by Gilmour and Waters: "I felt angry. It's like dirty linen in public and very unnecessary and unkind." Gilmour said: "Perhaps we were trying to show what Syd was really like. But perhaps we were trying to punish him." Waters was more positive: "Syd is a genius."[100] Barrett said: "It's quite nice but I'd be very surprised if it did anything if I were to drop dead. I don't think it would stand as my last statement."[100]

Barrett (1970)

The second album, Barrett, was recorded more sporadically,[101] the sessions taking place between February and July 1970.[100][102] The album was produced by Gilmour,[100][103] and featured Gilmour on bass guitar, Richard Wright on keyboard and Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley. The first two songs attempted were for Barrett to play and/or sing to an existing backing track. However, Gilmour thought they were losing the "Barrett-ness". One track ("Rats") was originally recorded with Barrett on his own. That would later be overdubbed by musicians, despite the changing tempos. Shirley said of Barrett's playing: "He would never play the same tune twice. Sometimes Syd couldn't play anything that made sense; other times what he'd play was absolute magic." At times Barrett, who experienced synaesthesia,[9] would say: "Perhaps we could make the middle darker and maybe the end a bit middle afternoonish. At the moment it's too windy and icy."[100]

In a 1970 interview reprinted in 1975, Barrett mentions listening to Taj Mahal and Captain Beefheart.[104]

These sessions were happening while Pink Floyd had just begun to work on Atom Heart Mother. On various occasions, Barrett went to "spy" on the band as they recorded their album.[100]

Wright said of the Barrett sessions:

Doing Syd's record was interesting, but extremely difficult. Dave [Gilmour] and Roger did the first one (The Madcap Laughs) and Dave and myself did the second one. But by then it was just trying to help Syd any way we could, rather than worrying about getting the best guitar sound. You could forget about that! It was just going into the studio and trying to get him to sing.[105]

Performances

Despite the numerous recording dates for his solo albums, Barrett undertook very little musical activity between 1968 and 1972 outside the studio. On 24 February 1970, he appeared on John Peel's BBC radio programme Top Gear[100] playing five songs—only one of which had been previously released. Three would be re-recorded for the Barrett album, while the song "Two of a Kind" (written by Richard Wright) was a one-off performance.[106] Regarding "Two of a Kind", David Gilmour stated that Wright wrote the song but an increasingly confused Barrett insisted it was his own composition (and wanted to include it on The Madcap Laughs).[107] Barrett was accompanied on this session by Gilmour and Shirley who played bass and percussion,[100] respectively. These five songs were originally released on Syd Barrett: The Peel Session.

Gilmour and Shirley also backed Barrett for his one and only live concert during this period.[103] The gig took place on 6 June 1970 at the Olympia Exhibition Hall as part of a Music and Fashion Festival.[108] The trio performed four songs,[103] "Terrapin", "Gigolo Aunt", "Effervescing Elephant" and "Octopus". Poor mixing left the vocals barely audible until part-way through the last number.[108] At the end of the fourth song, Barrett unexpectedly but politely put down his guitar and walked off the stage.[103] The performance has been bootlegged.[108][109] Barrett made one last appearance on BBC Radio, recording three songs at their studios on 16 February 1971.[nb 6] All three came from the Barrett album. After this session, he took a hiatus from his music career that lasted more than a year, although in an extensive interview with Mick Rock and Rolling Stone in December, he discussed himself at length, showed off his new 12-string guitar, talked about touring with Jimi Hendrix and stated that he was frustrated in terms of his musical work because of his inability to find anyone good to play with.[110]

Later years (1972–2006)

Stars and final recordings

In February 1972, after a few guest spots in Cambridge with ex-Pink Fairies member Twink on drums and Jack Monck on bass using the name The Last Minute Put Together Boogie Band (backing visiting blues musician Eddie "Guitar" Burns and also featuring Henry Cow guitarist Fred Frith), the trio formed a short-lived band called Stars.[111] Though they were initially well received at gigs in the Dandelion coffee bar and the town's Market Square, one of their gigs at the Corn Exchange in Cambridge[112] with MC5 proved to be disastrous.[113] A few days after this final show, Twink recalled that Barrett stopped him on the street, showed him a scathing review of the gig they had played, and quit on the spot,[113] despite having played at least one subsequent gig at the same venue supporting Nektar.[72]

Free from his EMI contract on 9 May 1972, Barrett signed a document that ended his association with Pink Floyd, and any financial interest in future recordings.[114] He attended an informal jazz and poetry performance by Pete Brown and former Cream bassist Jack Bruce in October 1973. Brown arrived at the show late, and saw that Bruce was already onstage, along with "a guitarist I vaguely recognised", playing the Horace Silver tune "Doodlin'". Later in the show, Brown read out a poem, which he dedicated to Syd, because, "he's here in Cambridge, and he's one of the best songwriters in the country" when, to his surprise, the guitar player from earlier in the show stood up and said, "No, I'm not".[115]

By the end of 1973, Barrett had returned to live in London, staying at various hotels and, in December of that year, settling in at Chelsea Cloisters. He had little contact with others, apart from his regular visits to his management's offices to collect his royalties,[111] and the occasional visit from his sister Rosemary.

In August 1974,[111] Jenner persuaded Barrett to return to Abbey Road Studios in hope of recording another album. According to John Leckie, who engineered these sessions, even at this point Syd still "looked like he did when he was younger ... long haired".[116] The sessions lasted three days and consisted of blues rhythm tracks with tentative and disjointed guitar overdubs. Barrett recorded eleven tracks, the only one of which to be titled was "If You Go, Don't Be Slow". Once again, Barrett withdrew from the music industry, but this time for good. He sold the rights to his solo albums back to the record label and moved into a London hotel. During this period, several attempts to employ him as a record producer (including one by Jamie Reid on behalf of the Sex Pistols, and another by The Damned, who wanted him to produce their second album) were fruitless.[117][118]

Wish You Were Here sessions

Barrett visited the members of Pink Floyd in 1975 during the recording sessions for their ninth album, Wish You Were Here. He attended the Abbey Road session unannounced, and watched the band working on the final mix of "Shine On You Crazy Diamond"—a song about him. Barrett, then 29, was overweight and had shaved off all of his hair (including his eyebrows), and his former bandmates did not initially recognise him. Barrett spent part of the session brushing his teeth.[119][120] Waters asked him what he thought of the song to which Barrett responded "sounds a bit old".[120] He is reported to have briefly attended the reception for Gilmour's wedding to Ginger that immediately followed the recording sessions, but Gilmour said he had no recollection of this.[121]

A few years later, Waters saw Barrett in the department store Harrods;[122][verification needed] Barrett ran away, dropping his bags, which Waters said were filled with candy.[113]

Withdrawal to Cambridge

In 1978, when Barrett's money ran out, he moved back to Cambridge to live with his mother. He returned to live in London for a few weeks in 1982, but soon returned to Cambridge permanently. Barrett walked the 50 miles (80 km) from London to Cambridge.[123] Until his death, he received royalties from his work with Pink Floyd; Gilmour said, "I made sure the money got to him."[124] In 1996, Barrett was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Pink Floyd. He did not attend the ceremony.[125]

According to the biographer and journalist Tim Willis, Barrett, who had reverted to using his birth name Roger, continued to live in his late mother's semi-detached home, and returned to painting, creating large abstract canvases. He was also an avid gardener. His main point of contact with the outside world was his sister, Rosemary, who lived nearby. He was reclusive, and his physical health declined, as he had stomach ulcers and type 2 diabetes.[126]

Although Barrett had not appeared or spoken in public since the mid-1970s, reporters and fans travelled to Cambridge seeking him, despite public appeals from his family to stop.[127] Apparently, Barrett did not like being reminded about his musical career and the other members of Pink Floyd had no direct contact with him. According to The Observer, he visited his sister's house in November 2001 to watch the BBC Omnibus documentary made about him, said it was "a bit noisy", enjoyed seeing Mike Leonard again (calling him his "teacher"), and enjoyed hearing "See Emily Play".[128] However, in 2024 his sister denied this event took place.[129]

Barrett made a final public acknowledgement of his musical past in 2002, his first since the 1970s, when he autographed 320 copies of Psychedelic Renegades, a book by the photographer Mick Rock which contained a number of photos of Barrett. Rock had conducted Barrett's final interview in 1971 before his retirement from the music industry, and Barrett visited Rock in London several times for tea and conversation in 1978.[130] They had not spoken in more than 20 years when Rock approached Barrett to autograph his book, and Barrett uncharacteristically agreed. Having reverted to his birth name, he autographed the book "Barrett".[130]

Death and tributes

Barrett died at home in Cambridge on 7 July 2006[23] aged 60, from pancreatic cancer.[131][132] His death was reported a week later on 12 July.[133] He was cremated at a funeral held at Cambridge Crematorium on 18 July 2006; no Pink Floyd members attended. In a statement, Wright said: "The band are very naturally upset and sad to hear of Syd Barrett's death. Syd was the guiding light of the early band lineup and leaves a legacy which continues to inspire."[133] Gilmour said: "Do find time to play some of Syd's songs and to remember him as the madcap genius who made us all smile with his wonderfully eccentric songs about bikes, gnomes, and scarecrows. His career was painfully short, yet he touched more people than he could ever know."[134]

NME produced a tribute issue to Barrett a week later with a photo of him on the cover. In an interview with The Sunday Times, Barrett's sister, Rosemary Breen, said that he had written an unpublished book about the history of art.[135] According to local newspapers, Barrett left approximately £1.7 million to his four siblings,[136] largely acquired from royalties from Pink Floyd compilations and live recordings featuring Barrett's songs.[124] A tribute concert, "Madcap's Last Laugh",[137] was held at the Barbican Centre, London, on 10 May 2007 with Barrett's bandmates and Robyn Hitchcock, Captain Sensible, Damon Albarn, Chrissie Hynde and Kevin Ayers.[138] Gilmour, Wright and Mason performed the Barrett compositions "Bike" and "Arnold Layne", and Waters performed a solo version of his song "Flickering Flame".[139]

In 2006, Barrett's home in St. Margaret's Square, Cambridge, was put on the market and attracted considerable interest.[140] After over 100 showings, many to fans, it was sold to a French couple who knew nothing about Barrett.[141] On 28 November 2006, Barrett's other possessions were sold at an auction at Cheffins auction house in Cambridge, raising £120,000 for charity.[142] Items sold included paintings, scrapbooks and everyday items that Barrett had decorated.[143] His small, paperback copy of cambridge 2005 [sic] has the handwritten inscription "RB '06" inside the front cover.[clarification needed]

A series of events called The City Wakes was held in Cambridge in October 2008 to celebrate Barrett's life, art, and music. Breen supported this, the first series of official events in memory of her brother.[144] After the festival's success, arts charity Escape Artists announced plans to create a centre in Cambridge, using art to help people with mental health problems.[145] A memorial bench was placed in the Botanic Gardens in Cambridge and a more prominent tribute was planned in the city.[146]

Legacy

Compilations

In 1988, EMI Records (after constant pressure from Malcolm Jones)[147] made an album of Barrett's studio out-takes and unreleased material recorded from 1968 to 1970 under the title Opel.[148] The disc was originally set to include the unreleased Barrett Pink Floyd songs "Scream Thy Last Scream" and "Vegetable Man", which had been remixed for the album by Jones,[147] but the band pulled the two songs[149] before Opel was finalised.[150] In 1993 EMI issued another release, Crazy Diamond, a boxed set of all three albums, each with further out-takes from his solo sessions that illustrated Barrett's inability or refusal to play a song the same way twice.[151] EMI also released The Best of Syd Barrett: Wouldn't You Miss Me? in the UK on 16 April 2001 and in the US on 11 September 2001.[152] This was the first time his song "Bob Dylan Blues" was officially released, taken from a demo tape that Gilmour had kept after an early 1970s session.[152] Gilmour kept the tape, which also contains the unreleased "Living Alone" from the Barrett sessions.[153] In October 2010 Harvest/EMI and Capitol Records released An Introduction to Syd Barrett—a collection of both his Pink Floyd and remastered solo work.[154] The 2010 compilation An Introduction to Syd Barrett includes the downloadable bonus track "Rhamadan", a 20-minute track recorded at one of Syd's earliest solo sessions, in May 1968. In 2011, it was announced that a vinyl double album version would be issued for Record Store Day.[155][156]

Bootleg editions of Barrett's live and solo material exist.[157][158] For years the "off air" recordings of the BBC sessions with Barrett's Pink Floyd circulated, until an engineer who had taken a tape of the early Pink Floyd gave it back to the BBC—which played it during a tribute to John Peel on their website. During this tribute, the first Peel programme (Top Gear) was aired in its entirety. This show featured the 1967 live versions of "Flaming", "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun", and a brief 90-second snippet of the instrumental "Reaction in G". In 2012, engineer Andy Jackson said he had found "a huge box of assorted tapes", in Mason's possession, containing versions of R&B songs that (the Barrett-era) Pink Floyd played in their early years.[159]

Creative impact

Barrett wrote most of Pink Floyd's early material, and their producer, Norman Smith compared him favourably with John Lennon in his memoir: "Syd Barrett could write like John. I've said it before. He wasn't quite as good as John, and I am talking about a Syd on top form with 'See Emily Play'. But he would have developed. Definitely! In time he would have got even better."[160] Jimmy Page never saw Barrett play with the Floyd, but was a fan of the early group's music, telling an interviewer, "Syd Barrett's writing with the early Pink Floyd was inspirational. Nothing sounded like Barrett before Pink Floyd's first album. There were so many ideas and so many positive statements. You can really feel the genius there, and it was tragic that he fell apart. Both he and Jimi Hendrix had a futuristic vision in a sense."[161] According to critic Steven Hyden, even after Barrett left the band, Barrett's spirit "haunted" their records, and their most popular work "drew on the power of what Barrett signified".[162]

Barrett was an innovative guitarist, using extended techniques and exploring the musical and sonic possibilities of dissonance, distortion, feedback, the echo machine, tapes and other effects; his experimentation was partly inspired by free improvisation guitarist Keith Rowe of the group AMM, active at the time in London.[163] Rowe would lay the guitar flat on a table and, among other things, would run ball bearings, metal rulers, coins, or knives along the strings.[164] AMM and Pink Floyd played several gigs together from early 1966 to early 1967, and Barrett even attended the recording session for the group's debut album, "AMMMusic", in June 1966.[165] One of Barrett's trademarks was playing his guitar through an old echo box while sliding a Zippo lighter up and down the fret-board to create the mysterious, otherworldly sounds that became associated with the group. Barrett was known to have used Binson delay units to achieve his trademark echo sounds. Daevid Allen, founder member of Soft Machine and Gong, cited Barrett's use of slide guitar with echo as a key inspiration for his own "glissando guitar" style.[166]

Barrett's recordings both with Pink Floyd and in later solo albums were delivered with a strongly British-accented vocal delivery, specifically that of southern England. He was described by Guardian writer Nick Kent as having a "quintessential English style of vocal projection".[167] David Bowie said that Barrett, along with Anthony Newley, was the first person he had heard sing rock or pop music with a British accent.[168]

Barrett's free-form sequences of "sonic carpets" pioneered a new way to play the rock guitar.[169] He played several different guitars during his tenure, including an old Harmony hollowbody electric, a Harmony acoustic, a Fender acoustic, a single-coil Danelectro 59 DC,[170] several different Fender Telecasters and a white Fender Stratocaster in late 1967. A silver Fender Esquire with mirrored discs glued to the body[171] was the guitar he was most often associated with and the guitar he "felt most close to".[110] The mirrored Esquire was traded for a black Telecaster Custom, in 1968. Its whereabouts are currently unknown.[172]

Influence

Many artists have acknowledged Barrett's influence on their work. Paul McCartney, Pete Townshend,[173] Blur,[174][175][176] Kevin Ayers,[177] Gong,[177] Marc Bolan,[175][178] Tangerine Dream,[179] Genesis P-Orridge,[180][181] Julian Cope,[182] Pere Ubu,[183] Jeff Mangum,[184] The Olivia Tremor Control,[185] The Flaming Lips,[186] Animal Collective,[187] John Maus,[188] Paul Weller, Roger Miller, East Bay Ray, Cedric Bixler-Zavala,[189] and David Bowie[175][178] were inspired by Barrett; Jimmy Page, Brian Eno,[190] Sex Pistols,[191] and The Damned[117][192] all expressed interest in working with him at some point during the 1970s. Bowie recorded a cover of "See Emily Play" on his 1973 album Pin Ups.[193] The track "Grass", from XTC's album Skylarking was influenced when Andy Partridge let fellow band member Colin Moulding borrow his Barrett records. Robyn Hitchcock's career was dedicated to being Barrett-esque; he even played "Dominoes" for the 2001 BBC documentary The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story.[182]

Barrett also had an influence on alternative and punk music in general. According to critic John Harris:

To understand his place in modern music you probably have to first go back to punk rock and its misguided attempt to kick aside what remained of the psychedelic 1960s. Given that the Clash and Sex Pistols had made brutal social commentary obligatory, there seemed little room for any of the creative exotica that had defined the Love Decade—until, slowly but surely, singing about dead-end lives and dole queues began to pall, and at least some of the previous generation were rehabilitated. Barrett was the best example: having crashed out of Pink Floyd before the advent of indulgent "progressive" rock, and succumbed to a fate that appealed to the punk generation's nihilism, he underwent a revival.[194]

Barrett's decline had a profound effect on Waters' songwriting, and the theme of mental illness permeated the later Pink Floyd albums The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975) and The Wall (1979).[195] The reference to a "steel rail" in the song "Wish You Were Here"[196]—"can you tell a green field from a cold steel rail?"—references a recurring theme in Barrett's song "If It's In You" from The Madcap Laughs. The song suite "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" from Wish You Were Here is also a tribute to Barrett.[197]

In 1987, an album of Barrett cover songs called Beyond the Wildwood was released. The album was a collection of cover songs from Barrett's tenure with Pink Floyd and from his solo career. Artists appearing were UK and US indie bands including The Shamen, Opal, The Soup Dragons, and Plasticland.[198]

Other artists who have written tributes to Barrett include his contemporary Kevin Ayers, who wrote "O Wot a Dream" in his honour (Barrett provided guitar to an early version of Ayers' song "Religious Experience: Singing a Song in the Morning").[94][96] Robyn Hitchcock has covered many of his songs live and on record and paid homage to his forebear with the song "(Feels Like) 1974". Phish covered "Bike", "No Good Trying", "Love You", "Baby Lemonade" and "Terrapin". The Television Personalities' single "I Know Where Syd Barrett Lives"[176] from their 1981 album And Don't the Kids Love It is another tribute.[nb 7] In 2008, The Trash Can Sinatras released a single in tribute to the life and work of Syd Barrett called "Oranges and Apples", from their 2009 album In the Music. Proceeds from the single go to the Syd Barrett Trust in support of arts in mental health.

Johnny Depp showed interest in a biographical film based on Barrett's life.[200] Barrett is portrayed briefly in the opening scene of Tom Stoppard's play Rock 'n' Roll (2006), performing "Golden Hair". His life and music, including the disastrous Cambridge Corn Exchange concert and his later reclusive lifestyle, are a recurring motif in the work.[201][202] Barrett died during the play's run in London.

In 2016, in correspondence with the 70th anniversary birthday, The Theatre of the Absurd, an Italian independent artists group, published a short movie in honour of Barrett named Eclipse, with actor-director Edgar Blake in the role of Barrett. Some footage from this movie was also shown at Syd Barrett – A Celebration during Men on the Border's tribute: the show took place at the Cambridge Corn Exchange, with the participation of Barrett's family and old friends.[203]

For 2017 TV series Legion creator Noah Hawley named one of the characters after Barrett, whose music was an important influence on the series.[204]

In The X-Files season nine episode, "Lord of the Flies" (2001), a powerful mutant, Dylan Lokensgard (Hank Harris), has several posters of Syd Barrett on his bedroom wall, and listens to "It's No Good Trying" and "Terrapin" from The Madcap Laughs.[205][206][207] He recites the line, "A dream in a mist of gray", from Barrett's song "Opel", saying of the singer, "He was, like, this brilliant guy that no-one understood".[208]

Barrett's influence on the genesis of psychedelia was considered in a chapter entitled "Astronauts of Inner Space: Syd Barrett, Nick Drake and the Birth of Psychedelia" in Guy Mankowski's book Albion's Secret History: Snapshots of England's Pop Rebels and Outsiders.[209]

The 2023 documentary film Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd features interviews with Roger Waters, Nick Mason, David Gilmour, Barrett's sister Rosemary Breen, and Pink Floyd managers Peter Jenner and Andrew King. It is directed by Roddy Bogawa and Storm Thorgerson, and narrated by Jason Isaacs.[210][211]

Health

Members of Barrett's family denied that he was mentally ill.[9] Asked if Barrett may have had Asperger's syndrome, his sister Rosemary Breen said that he and his siblings were "all on the spectrum".[9][212] She also stated that, contrary to common misconception,[213] Barrett neither suffered from mental illness nor had he received treatment for it since they had resumed regular contact in the 1980s.[214] Breen said he had spent some time in a private "home for lost souls"—Greenwoods in Essex—but that there was no formal therapy programme there. Some years later, Barrett agreed to sessions with a psychiatrist at Fulbourn psychiatric hospital in Cambridge, but Breen said that neither medication nor therapy was considered appropriate.[214] Breen also denied Barrett was a recluse or that he was vague about his past: "Roger may have been a bit selfish—or rather self-absorbed—but when people called him a recluse they were really only projecting their own disappointment. He knew what they wanted, but he wasn't willing to give it to them."[215] In 1996, Wright said that Barrett's mother told the members of Pink Floyd not to contact him because being reminded of the band would make him depressed for weeks.[216]

Opinions of Pink Floyd members

In the 1960s, Barrett used psychedelic drugs, especially LSD, and there are theories he subsequently had schizophrenia.[81][217][218] Wright asserted that Barrett's problems stemmed from a massive overdose of acid, as the change in his personality and behaviour came on suddenly. However, Waters maintains that Barrett suffered "without a doubt" from schizophrenia.[9] In an article published in 2006, Gilmour was quoted as saying: "In my opinion, his nervous breakdown would have happened anyway. It was a deep-rooted thing. But I'll say the psychedelic experience might well have acted as a catalyst. Still, I just don't think he could deal with the vision of success and all the things that went with it."[219] According to Gilmour in a 1974 interview, the other members of Pink Floyd approached psychiatrist R. D. Laing with the "Barrett problem". After hearing a tape of a Barrett conversation, Laing declared him "incurable".[220][221]

Opinions of others

In Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey, author Nicholas Schaffner interviewed people who knew Barrett before and during his Pink Floyd days, including friends Peter and Susan Wynne-Wilson, artist Duggie Fields (with whom Barrett shared a flat during the late 1960s), June Bolan, and Storm Thorgerson. Bolan became concerned when Syd "kept his girlfriend under lock and key for three days, occasionally shoving a ration of biscuits under the door".[222] A claim of cruelty against Barrett committed by the groupies and hangers-on who frequented his apartment during this period was described by writer and critic Jonathan Meades. "I went [to Barrett's flat] to see Harry and there was this terrible noise. It sounded like heating pipes shaking. I said, 'What's up?' and he sort of giggled and said, 'That's Syd having a bad trip. We put him in the linen cupboard'".[223] Storm Thorgerson responded to this claim by stating "I do not remember locking Syd up in a cupboard. It sounds to me like pure fantasy, like Jonathan Meades was on dope himself."[223] Aubrey Powell added that they probably told Meades this, but only to "wind him up".[128]

Other friends state that Barrett's flatmates, who had also taken LSD, thought of Barrett as a genius or a deity, and were spiking his morning coffee every day without his knowledge, leaving him in a never-ending trip. He was later rescued from that flat by friends and moved elsewhere, but his erratic behaviour continued.[9] According to Thorgerson, "On one occasion, I had to pull him [Barrett] off [his girlfriend] Lindsay because he was beating her over the head with a mandolin";[224] Powell recalled this event as well, although Corner later denied this happened.[128] On one occasion, Barrett threw a woman called Gilly across the room, because she refused to go to Gilmour's house.[113]

Personal life

According to his sister, Rosemary, Barrett took up photography and sometimes they went to the seaside together. She also said he took a keen interest in art and horticulture and continued to devote himself to painting:

Quite often he took the train on his own to London to look at the major art collections—and he loved flowers. He made regular trips to the Botanic Gardens and to the dahlias at Anglesey Abbey, near Lode. But of course, his passion was his painting.[214][128]

Barrett had relationships with various women, such as Libby Gausden; Lindsay Korner; Jenny Spires; and Pakistani-born Evelyn "Iggy" Rose (1947–2017) (aka "Iggy the Eskimo", "Iggy the Inuit"), who appeared on the back cover of The Madcap Laughs.[9][225][226] He never married or had children,[227] though he was briefly engaged to marry Gayla Pinion and planned to relocate to Oxford.[228]

Discography

Solo albums

- The Madcap Laughs (1970)

- Barrett (1970)

with Pink Floyd

- The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

- A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

- 1965: Their First Recordings (2015)

- The Early Years 1965–1972 (2016)

Filmography

- Syd Barrett's First Trip (1966) directed by Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon[229]

- London '66–'67 (1967)

- Tonite Let's All Make Love in London (1967)

- The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story (2003)

- Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd (2023)

See also

References

Informational notes

- ^ Barrett devised the name "Pink Floyd" by juxtaposing the first names of Pink Anderson and Floyd Council[40] whom he had read about in a sleeve note for a 1962 Blind Boy Fuller album: "Curley Weaver and Fred McMullen, [...] Pink Anderson or Floyd Council—these were a few amongst the many blues singers who were to be heard in the rolling hills of the Piedmont, or meandering with the streams through the wooded valleys."[41][42]

- ^ While under the influence of the acid, Barrett had placed an orange, a plum and a matchbox in a corner, and then stared at this arrangement, which he claimed symbolised "Venus and Jupiter".[43][44] Thorgerson later added these items to the cover of the double album combination of Barrett's solo albums, Syd Barrett.[43]

- ^ The band were still playing R&B hits as late as early 1966,[50][51] however, mixed in with several original songs: "Let's Roll Another One", "Lucy Leave", "Butterfly", "Remember Me" and "Walk with Me Sydney".[50]

- ^ Barrett, frequently at his Earlham Street residence, played The Mothers of Invention's Freak Out!, The Byrds' Fifth Dimension, The Fugs' and Love's debut albums,[52] and The Beatles' Revolver,[53] repeatedly. All these albums were connected by their proto-psychedelic feel, which had begun to guide Barrett's songs, as much as R&B had, previously.[52] "Interstellar Overdrive" (included into the band's setlist from autumn), for example, was inspired by the riff from Love's "My Little Red Book", the free-form section (and also, "Pow R. Toc H.") was inspired by Frank Zappa's free-form freak-outs and The Byrds' "Eight Miles High". The Kinks' "Sunny Afternoon" was an important influence on Barrett's songwriting.[52]

- ^ The demo recordings consist of "I Get Stoned" (aka "Stoned Alone"), "Let's Roll Another One", "Lucy Leave" and a 15-minute version of "Interstellar Overdrive".[56]

- ^ These three songs, along with the five from the Top Gear performance, were released on Syd Barrett: The Radio One Sessions.

- ^ The Television Personalities became the subject of controversy and derision when, as they had been selected as the opening act on Gilmour's About Face tour in the early 1980s, lead singer Dan Treacy decided to read aloud Barrett's real home address to the audience of thousands. Gilmour removed them from the tour immediately afterwards.[199]

Citations

- ^ a b Reed, Ryan (29 June 2013). "How Pink Floyd Carried On With 'A Saucerful of Secrets'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Paytress, Matt (14 February 2001). "Syd Barrett Song Unearthed". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Faulk, Barry J. (2016). British Rock Modernism, 1967–1977. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-317-17152-2.

...Most of the musicians at the forefront of the experimental rock movement were on the rock casualty list: cracked up, like Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd...

- ^ Chapman 2010, pp. 144–148, 381–382.

- ^ Thomas, Stephen (11 October 2010). "Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "UPI Almanac for Sunday, Jan. 6, 2019". United Press International. 6 January 2019. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member Syd Barrett (Pink Floyd) in 1946

- ^ a b c d e f Manning 2006, p. 8

- ^ a b Chapman 2010, pp. 3–4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Palacios 2010.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 13

- ^ a b Chapman 2010, p. 4

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c Palacios 1997

- ^ a b c d e f g Manning 2006, p. 10.

- ^ a b Chapman 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Mason 2011.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 11–12.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 9.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 31.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 33.

- ^ a b "Seeing Pink – a Floyd gazetteer of Cambridge". Cambridge Evening News. 17 October 2007. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 22-23.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 40

- ^ a b c Manning 2006, p. 11

- ^ "Syd Barrett interview". www.sydbarrett.net. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c d e Manning 2006, p. 12

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 50

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 58

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 45

- ^ "Syd Barrett obit". The Times. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e Chapman 2010, p. 52

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 15

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 43

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 53

- ^ "Floyd Council". Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d Manning 2006, p. 19

- ^ a b c d Manning 2006, p. 17

- ^ a b Chapman 2010, pp. 76–77

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 18

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 73

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 99

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 124

- ^ a b Chapman 2010, p. 86

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 104

- ^ a b c d e Manning 2006, p. 26

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 132

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 25

- ^ Jones 2003, p. 27

- ^ a b Manning 2006, p. 28

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 32

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 34.

- ^ EMI Records Ltd., "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" insert

- ^ "PINK FLOYD | Artist". Official Charts. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 65.

- ^ Boyd 2009, p. 216 [ebook], pp. 140-141 [print].

- ^ "Syd Barrett". The Economist. 20 July 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 95.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Parker 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Willis 2002a, p. 102.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 42.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, pp. =13–14

- ^ a b Willis 2002a.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 94.

- ^ Mason 2011, pp. 95–105

- ^ "Gilmour interview in Guitar World". January 1995.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e Manning 2006, p. 45

- ^ Schaffner 2005, pp. 14–15

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Schaffner 2005, p. 14

- ^ a b DiLorenzo, Kris. "Syd Barrett: Careening Through Life." Trouser Press February 1978 pp. 26–32

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 334.

- ^ a b 1993 Guitar World interview with David Gilmour

- ^ a b Schaffner 2005, p. 15

- ^ Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd – The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ^ The Dark Star – Syd Barrett, Clash Music, 27 June 2011

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 9.

- ^ a b Jones 2003, p. 3

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e f g Manning 2006, p. 71

- ^ BdF. "Prose". Duggie Fields. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Jones 2003, p. 4

- ^ Jones 2003, pp. 3–4

- ^ a b c Manning 2006, p. 27

- ^ Bush, John (23 April 2012). "The Harvest Years 1969–1974 – Kevin Ayers : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b Palacios 2010, p. 362

- ^ Parker 2001, p. iv.

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ^ "David Gilmour: Record Collector, May 2003 – All Pink Floyd Fan Network". Pinkfloydfan.net. 10 January 2001. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Manning 2006, p. 72

- ^ Kent, Nick (2007). The Dark Stuff: Selected Writings on Rock Music. Faber & Faber, Limited. p. 121.

- ^ Barrett (booklet). Syd Barrett. Harvest, EMI. 1970. pp. 1–2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b c d Manning 2006, p. 61

- ^ "Syd Barrett interview". www.sydbarrett.net. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Rick Wright: Broken China Interview – Aug 1996 – All Pink Floyd Fan Network". Pinkfloydfan.net. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Edginton, John. "PINK FLOYD'S RICHARD WRIGHT FULL UNCUT INTERVIEW". JOHN EDGINTON DOCUMENTARIES. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 2001, p. 92

- ^ a b c Chapman 2010, p. 270

- ^ "RoIO LP: He Whom Laughs First". Pf-roio.de. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

"The International Echoes Hub – Recordings (RoIO) Database: Tatooed". Echoeshub.com. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

"The International Echoes Hub – Recordings (RoIO) Database: Olympia Exhibition Hall". Echoeshub.com. Retrieved 4 October 2012. - ^ a b Rock, Mick (December 1971). "The Madcap Who Named Pink Floyd". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

If you tend to believe what you hear, rather than what is, Syd Barrett is either dead, behind bars, or a vegetable. He is in fact alive and as confusing as ever, in the town where he was born, Cambridge.

- ^ a b c Manning 2006, p. 74

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. xv

- ^ a b c d Manning 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 400

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 401.

- ^ Parker 2001, p. 194.

- ^ a b Watkinson & Anderson 2001, pp. 121–122

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 213.

- ^ "The Syd Barrett story". Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ a b Palacios 2010, p. 408

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 231.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 412.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 414.

- ^ a b "Barrett leaves £1.25m". Cambridge Evening News. 11 November 2006. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Povey, Glenn (2007). Echoes – The Complete History of Pink Floyd. Mind Head Publishing. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5.

- ^ Gilmore, Mikal (5 April 2007). "The Madness and Majesty of Pink Floyd". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007.

- ^ "Set The Controls; Interview to Roger 'Syd' Barrett's Nephew". Pink-floyd.org. 22 April 2001. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d Willis, Tim (6 October 2002). "You shone like the sun". The Observer. London. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ^ "Ep.9 - Rosemary Breen on her Brother Syd Barrett: "He never sought celebrity"". Fingal's Cave Podcast. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b Cavanagh, David (September 2006). "The glory and torment of being Syd Barrett, by David Bowie, David Gilmour, Mick Rock, Joe Boyd, Damon Albarn and more..." Uncut. London. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 2001.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (31 December 2006). "Off-Key". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon (12 July 2006). "Syd Barrett, a Founder of Pink Floyd And Psychedelic Rock Pioneer, Dies at 60". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Co-Founder Syd Barrett Dies At 60". Billboard. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "My lovably ordinary brother Syd". The Sunday Times. July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "'Poverty-stricken' Syd Barrett and the Ł1.7m inheritance | Showbiz". Thisislondon.co.uk. 17 May 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Blake, Mark: Pigs Might Fly – The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, p.. 395, 2007, Aurum

- ^ Youngs, Ian (11 May 2007). "Floyd play at Barrett tribute gig". BBC News. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ Youngs, Ian (11 May 2007). "Floyd play at Barrett tribute gig". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Syd Barrett's home on the market". BBC News. 11 September 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ^ Smith, Andrew (4 August 2007). "Making tracks: Visiting England's semi-secret rock shrines". Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ "Syd's poem auctioned for £4,600". Cambridge Evening News. 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- ^ "Barrett paintings fetch thousands". BBC. 29 November 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Plea for memories of Floyd rocker". Cambridge Evening News. 17 July 2008. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ "Project in Syd's memory". Cambridge Evening News. 17 July 2008. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Pink Floyd memorial for Syd Barrett". Cambridge-news.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b Palacios 2010, p. 419

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Opel – Syd Barrett : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 186.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Crazy Diamond – Syd Barrett : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b Kellman, Andy (27 March 2001). "Wouldn't You Miss Me?: The Best of Syd Barrett – Syd Barrett : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Parker 2003

- ^ Thomas, Stephen (11 October 2010). "An Introduction to Syd Barrett – Syd Barrett : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Wyman, Howard (23 February 2011). "Introduction to Syd Barrett Ltd. 2LP Vinyl Coming for Record Store Day". Crawdaddy!. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "An Introduction to Syd Barrett – Syd Barrett : Releases". AllMusic. 11 October 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Pink Floyd RoIO Database Homepage". Pf-roio.de. 17 May 1994. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Marooned. "RoIO Audience/Soundboard Concert Database". Echoeshub.com. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

Unterberger, Richie. "Syd Barrett – Music Biography, Credits and Discography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012. - ^ Graff, Gary (8 February 2012). "Pink Floyd Mulling More Reissues After Expanded 'Wall' Releases". billboard.com. Detroit. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 220.

- ^ Tolinski 2012.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (2018). Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic Rock. Dey Street. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-06-265712-1.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Chapman 2010, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 99.

- ^ "Gong Family Maze | MizMaze / DaevidAllen". Planetgong.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ – Shine on you crazy diamond – The Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Pink Floyd's Barrett dies aged 60 – BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Denyer, Ralph (1992). The Guitar Handbook. London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd. ISBN 0-679-74275-1, p 23

- ^ "'68 Flashback: How Pink Floyd Found Their Future and Lost Psychedelic Genius Syd Barrett in A Saucerful of Secrets". Gibson.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 126

- ^ Baker, Alex (9 February 2017). "Psych Out: Syd Barrett's '62 Esquire and the Dawn of Pink Floyd". Fender.com. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 246

- ^ "Blur's Graham Coxon on Syd Barrett". YouTube. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ a b c "Pink Floyd Interviews". Pinkfloydz.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015.

- ^ a b Harris, John (12 July 2006). "John Harris on Syd Barrett's influence | Music". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ a b Manning 2006, p. 285

- ^ a b Manning 2006, p. 286

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 285–286.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (15 March 2020). "The extraordinary life and times of Genesis P-Orridge". Louder Sound. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Venker, Thomas (7 June 2015). "Genesis P-Orridge – Kaput Mag". Kaput Magazine. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

I saw the Rolling Stones in Hyde Park, I saw the first gigs by King Crimson, I saw Syd Barrett, all that stuff, live, over and over and over. So these are my roots, you know?

- ^ a b Manning 2006, p. 287

- ^ Smith, John (12 April 1996). "John Eric Smith Interviews Jim Jones, 12/4/96". Ubuprojex. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

Our determination was to expand upon the rich areas pioneered by bands such as The Stooges, Velvet Underground, Capt. Beefheart, MC5 & Syd Barrett's Pink Floyd. Bands that NEVER got played on commercial radio.

- ^ Hellweg, Eric (2 April 1998). "New & Cool: The Surreal Sound Of Neutral Milk Hotel". MTV. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

When asked about his musical influences, Mangum hedges before citing Pink Floyd-founder and fantastical lyricist, Syd Barrett, as well as many forms of world music, country and jazz.

- ^ Allen, Jim (31 July 2012). "Olivia Tremor Control's Bill Doss Dies". MTV. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

I heard MGMT, and I've heard people say 'Oh they're obviously influenced by Elephant 6,' but what I heard was them being influenced by what we were influenced by, because it sounded really like Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd.

- ^ Wener, Ben (21 June 2006). "Pop Life column: What will these freaks think up next?". Orange County Register. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Clements, Erin (23 January 2009). "We're With The Band: Animal Collective". Elle. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Mejia, Paula (26 October 2017). "John Maus: Baroque and Roll". Red Bull Music Academy. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Weller, Miller and Ray have all called Barrett one of their favourite guitarists, whilst Bixler-Zavala calls him an influence on his music with The Mars Volta. See: Palacios 2010

- ^ "CRACKED BALLAD OF SYD BARRETT – 1974". Luckymojo.com. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "John Lydon: I don't hate Pink Floyd". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 214.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Pin Ups – David Bowie : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ John Harris (12 July 2006). "Barrett's influence". The Guardian.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 16

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 18

- ^ The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story (Documentary). BBC. 2003.

- ^ Rabid, Jack. "Beyond the Wildwood – Various Artists : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 123

- ^ Douglas, Edward (29 June 2005). "In the Future: Chocolate Factory Cast & Crew". Coming Soon.net. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- ^ Stoppard, Tom (21 March 2012). "Here's Looking at You, Syd | Culture". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "'Rock 'N' Roll': Syd Barrett On Broadway, By Kurt Loder – Music, Celebrity, Artist News". MTV.com. 11 May 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

Sean O'Hagan (30 July 2006). "Theatre: Rock'n'Roll | Stage | The Observer". Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 July 2012. - ^ Cambridge honours its 'Crazy Diamond'

- ^ Desta, Yohana (9 October 2016). "The Surprising Connection Between Marvel's Legion and Pink Floyd". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Chris Carter (2005). The X Files Season 9 (Media notes). UK release: Twentieth Century Fox. ASIN : B0002OI074.

- ^ "Music from the X-Files S9E05".

- ^ ""The X-Files" Lord of the Flies (TV Episode 2001) – IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ ""The X-Files" Lord of the Flies (TV Episode 2001) – IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ Foster, Richard. "Guy Mankowski – Albion's Secret History, Snapshots of England's Pop Rebels and Outsiders – Book Review". Louder Than War.

- ^ Skinner, Tom (15 October 2022). "Syd Barrett to be subject of new documentary, 'Have You Got It Yet?'". NME. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Hadusek, Jon (26 April 2023). "Documentary on Pink Floyd's Syd Barrett Unveils Official Trailer". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Mojo magazine, June 2016, p. 71

- ^ "Pink Floyd news :: Brain Damage – Interview with Rosemary Breen, May 2009".

- ^ a b c Willis, Tim (16 July 2007). "My lovably ordinary brother Syd". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "My lovably ordinary brother Syd". 25 May 2023 – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ Polcaro, Rafael (6 September 2020). "Why Syd Barrett's mother asked Pink Floyd members to not talk to him". Rock and Roll Garage. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Greene, Andy (11 July 2006). "Founding frontman and songwriter for Pink Floyd dead at 60". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

The next year, following a highly successful tour with Jimi Hendrix, Barrett's mental state began to deteriorate ... Amid reports that he was suffering from schizophrenia, Barrett managed to release two solo albums in 1970 ...

- ^ "Syd Barrett, Founder of Pink Floyd band, Sufferer of Schizophrenia, Passed Away this Week." Schizophrenia Daily News Blog. 12 July 2006

- ^ "Syd Barrett, the swinging 60". The Independent. UK. 7 January 2006. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ Kent, Nick. "The Cracked Ballad of Syd Barrett". New Musical Express, 13 April 1974.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Schaffner 2005, p. 77.

- ^ a b Schaffner 2005, p. 110

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 2001, p. 83.

- ^ "The Holy Church of Iggy the Inuit". Atagong.com.

- ^ "Syd Barrett Girlfriends | Libby Gausden, Lindsay Korner, Iggy the Eskimo, Gayla Pinion". Neptunepinkfloyd.co.uk. 16 August 2010.

- ^ "The glory and torment of being Syd Barrett, by David Bowie, David Gilmour, Mick Rock, Joe Boyd, Damon Albarn and more…". Uncut.co.uk. 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Pink Floyd news :: Brain Damage – February 1978 – Source unknown". Brain-damage.co.uk.

- ^ Makey, Julian (1 November 2012). "Trip of a lifetime". Cambridge News. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

Bibliography

- Blake, Mark (2008). Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6.

- Boyd, Joe (2009). White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s (eBook ed.). London: Serpent's Tail. ISBN 978-1-84765-216-4.

- Chapman, Rob (2010). Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head (Paperback ed.). London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23855-2.

- Jones, Malcolm (2003). The Making of The Madcap Laughs (21st Anniversary ed.). Brain Damage.

- Manning, Toby (2006). The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (1st ed.). London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-575-1.

- Mason, Nick (2011) [2004]. Philip Dodd (ed.). Inside Out – A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Paperback ed.). Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-1906-7.

- Palacios, Julian (1997). Lost in the Woods: Syd Barrett and the Pink Floyd. Boxtree. ISBN 978-0-7522-2328-5.

- Palacios, Julian (2010). Syd Barrett & Pink Floyd: Dark Globe (Rev. ed.). London: Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-431-9.

- Parker, David (2003). Random Precision: Recording the Music of Syd Barrett 1965–1974. Cherry Red. ISBN 978-1-901447-25-5.

- Parker, David (2001). Random Precision: Recording the Music of Syd Barrett, 1965–1974. Cherry Red Books.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (2005). Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey (New ed.). London: Helter Skelter. ISBN 978-1-905139-09-5.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1991). Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey. New York: Delta Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-385306-84-3.

- Smith, Norman "Hurricane" (2008). John Lennon Called me Normal: "The Man that Got the Sound that Changed the World". United States: Norman Smith. ISBN 978-1-409202-90-5.

- Tolinski, Brad (2012). Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page. New York: Crown. ISBN 978-0307985712.

- Watkinson, Mike; Anderson, Pete (2001). Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett & the Dawn of Pink Floyd. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84609-739-3.

- Willis, Tim (2002a). Madcap: The Half-Life of Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd's Lost Genius. Short Books. ISBN 978-1-904095-24-8.

External links

- The Official Syd Barrett Website

- The Syd Barrett Archives

- Official trailer for Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd

- Syd Barrett at AllMusic

- Syd Barrett discography at Discogs