This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Flagellation (Latin flagellum, 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on an unwilling subject as a punishment; however, it can also be submitted to willingly and even done by oneself in sadomasochistic or religious contexts.

The strokes are typically aimed at the unclothed back of a person, though they can be administered to other areas of the body. For a moderated subform of flagellation, described as bastinado, the soles of a person's bare feet are used as a target for beating (see foot whipping).

In some circumstances the word flogging is used loosely to include any sort of corporal punishment, including birching and caning. However, in British legal terminology, a distinction was drawn (and still is, in one or two colonial territories[citation needed]) between flogging (with a cat o' nine tails) and whipping (formerly with a whip, but since the early 19th century with a birch). In Britain these were both abolished in 1948.

Current use as punishment

editOfficially abolished in most countries, flogging or whipping, including foot whipping in some countries, is still a common punishment in some parts of the world,[1] particularly in countries using Islamic law and in some territories which were former British colonies.[citation needed] Caning is routinely ordered by the courts as a penalty for some categories of crime in Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and elsewhere.[citation needed]

Syria

editIn Syria, where torture of political dissidents, POWs and civilians is extremely common,[2][3] flagellation has become one of the most common forms of torture.[4] Flagellation is used by both the Free Syrian Army[5] and the Syrian Arab Army,[6] but is not practiced by the Syrian Democratic Forces.[7] ISIS most commonly used flagellation in which people would be tied to a ceiling and whipped.[8] It was extremely common in Raqqa Stadium, a makeshift prison where prisoners were tortured.[9][10] It was also common for those who did not follow ISIS strict laws to be publicly flogged.

Historical use as punishment

editJudaism

editAccording to the Torah (Deuteronomy 25:1–3) and Rabbinic law lashes may be given for offenses that do not merit capital punishment, and may not exceed 40. However, in the absence of a Sanhedrin, corporal punishment is not practiced in Jewish law. Halakha specifies the lashes must be given in sets of three, so the total number cannot exceed 39. Also, the person whipped is first judged whether they can withstand the punishment, if not, the number of whips is decreased. Jewish law limited flagellation to forty strokes, and in practice delivered thirty-nine, so as to avoid any possibility of breaking this law due to a miscount.

Antiquity

editIn the Roman Empire, flagellation was often used as a prelude to crucifixion, and in this context is sometimes referred to as scourging. Most famously according to the gospel accounts, this occurred prior to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Due to the context of the flagellation of Jesus, the method and extent may have been limited by local practice, though it was done under Roman law.

Whips with small pieces of metal or bone at the tips were commonly used. Such a device could easily cause disfigurement and serious trauma, such as ripping pieces of flesh from the body or loss of an eye. In addition to causing severe pain, the victim would approach a state of hypovolemic shock due to loss of blood.

The Romans reserved this treatment for non-citizens, as stated in the lex Porcia and lex Sempronia, dating from 195 and 123 BC. The poet Horace refers to the horribile flagellum (horrible whip) in his Satires. Typically, the one to be punished was stripped naked and bound to a low pillar so that he could bend over it, or chained to an upright pillar so as to be stretched out. Two lictors (some reports indicate scourgings with four or six lictors) alternated blows from the bare shoulders down the body to the soles of the feet. There was no limit to the number of blows inflicted—this was left to the lictors to decide, though they were normally not supposed to kill the victim. Nonetheless, Livy, Suetonius and Josephus report cases of flagellation where victims died while still bound to the post. Flagellation was referred to as "half death" by some authors, as many victims died shortly thereafter. Cicero reports in In Verrem, "pro mortuo sublatus brevi postea mortuus" ("taken away for a dead man, shortly thereafter he was dead").

From Middle Ages to modern times

editThe Whipping Act was passed in England in 1530. Under this legislation, vagrants were to be taken to a nearby populated area "and there tied to the end of a cart naked and beaten with whips throughout such market town till the body shall be bloody".[11]

In England, offenders (mostly those convicted of theft) were usually sentenced to be flogged "at a cart's tail" along a length of public street, usually near the scene of the crime, "until his [or her] back be bloody". In the late seventeenth century, however, the courts occasionally ordered that the flogging should be carried out in prison or a house of correction rather than on the streets. From the 1720s courts began explicitly to differentiate between private whipping and public whipping. Over the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the proportion of whippings carried out in public declined, but the number of private whippings increased. The public whipping of women was abolished in 1817 (after having been in decline since the 1770s) and that of men ended in the early 1830s, though not formally abolished until 1862.

Private whipping of men in prison continued and was not abolished until 1948.[12] The 1948 abolition did not affect the ability of a prison's visiting[clarification needed] justices (in England and Wales, but not in Scotland, except at Peterhead) to order the birch or cat for prisoners committing serious assaults on prison staff. This power was not abolished until 1967, having been last used in 1962.[13] School whipping was outlawed in publicly funded schools in 1986, and in privately funded schools in 1998 to 2003.[14]

Whipping occurred during the French Revolution, though not as official punishment. On 31 May 1793, the Jacobin women seized a revolutionary leader, Anne Josephe Theroigne de Mericourt, stripped her naked, and flogged her on the bare bottom in the public garden of the Tuileries. After this humiliation, she refused to wear any clothes, in memory of the outrage she had suffered.[15] She went mad and ended her days in an asylum after the public whipping.

In the Russian Empire, knouts were used to flog criminals and political offenders. Sentences of a hundred lashes would usually result in death. Whipping was used as a punishment for Russian serfs.[16]

Ashraf Fayadh (born 1980), a Saudi Arabian poet, was imprisoned for eight years and lashed 800 times, rather than receiving a death penalty, for apostasy in 2016. In April 2020, Saudi Arabia said it would replace flogging with prison sentences or fines, according to a government document.[17]

Use against slaves

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

Whipping has been used as a form of discipline on slaves. It was sometimes carried out during the period of slavery in the United States, by slave owners and their slaves. The power was also given to slave "patrolers," whites authorized to whip any slave who violated the slave codes.

Flogging as military punishment

editIn the 18th and 19th centuries, European armies administered floggings to common soldiers who committed breaches of the military code.

United States

editDuring the American Revolutionary War, the American Congress raised the legal limit on lashes from 39 to 100 for soldiers who were convicted by courts-martial.[18]

Prior to 1815 United States Navy captains were given wide discretion in matters of discipline. Surviving ships logs reveal the majority awarded between twelve and twenty-four lashes, depending on the severity of the offense. However, a few such as captain Isaac Chauncey awarded one hundred or more lashes.[19] In 1815 the United States Navy placed a limit of twelve lashes, a captain of a naval vessel, could award. More severe infractions were to be tried by court martial.[20] As critics of flogging aboard the ships and vessels of the United States Navy became more vocal, the Department of the Navy began in 1846 to require annual reports of discipline including flogging, and limited the maximum number of lashes to 12. These annual reports were required from the captain of each naval vessel. See thumbnail for the 1847 disciplinary report of the USS John Adams. The individual reports were then compiled so the Secretary of the Navy could report to the United States Congress how pervasive flogging had become and to what extent it was utilized.[21] In total for the years 1846–1847, flogging had been administered a reported 5,036 times on sixty naval vessels.[22] At the urging of New Hampshire Senator John P. Hale, the United States Congress banned flogging on all U.S. ships in September 1850, as part of a then-controversial amendment to a naval appropriations bill.[23][24] Hale was inspired by Herman Melville's "vivid description of flogging, a brutal staple of 19th century naval discipline" in Melville's "novelized memoir" White Jacket.[25][23] During Melville's time on the USS United States from 1843 to 1844, the ship log records 163 floggings, including some on his first and second days (18 and 19 August 1843) aboard the frigate at Honolulu, Oahu.[26] Melville also included an intense depiction of flogging, and the circumstances surrounding it, in his more famous work, Moby-Dick.

Military flogging was abolished in the United States Army on 5 August 1861.[27]

United Kingdom

editFlagellation was so common in England as punishment that caning (and spanking and whipping) are called "the English vice".[28]

Flogging was a common disciplinary measure in the Royal Navy that became associated with a seaman's manly disregard for pain.[29] Generally, officers were not flogged. However, in 1745, a cashiered British officer's sword could be broken over his head, among other indignities inflicted on him.[30] Aboard ships, knittles or the cat o' nine tails was used for severe formal punishment, while a "rope's end" or "starter" was used to administer informal, on-the-spot discipline. During the period 1790–1820, flogging in the British Navy on average consisted of 19.5 lashes per man.[31] Some captains such as Thomas Masterman Hardy imposed even more severe penalties.[32] Hardy while commanding HMS Victory, 1803–1805, raised punishments from the prior twelve lashes and twenty-four for more serious offenses to a new standard of thirty-six lashes with sixty lashes reserved for more serious infractions, such as theft or second offenses.[33]

In severe cases a person could be "flogged around the fleet": a significant number of lashes (up to 600) was divided among the ships on a station and the person was taken to all ships to be flogged on each, or—when in harbour—bound in a ship's boat which was then rowed among the ships, with the ships' companies called to attention to observe the punishment.[34]

In June 1879 a motion to abolish flogging in the Royal Navy was debated in the House of Commons. John O'Connor Power, the member for Mayo, asked the First Lord of the Admiralty to bring the navy cat o' nine tails to the Commons Library so that the members might see what they were voting about. It was the Great "Cat" Contention, "Mr Speaker, since the Government has let the cat out of the bag, there is nothing to be done but to take the bull by the horns." Poet Laureate Ted Hughes celebrates the occasion in his poem, "Wilfred Owen's Photographs": "A witty profound Irishman calls/For a 'cat' into the House, and sits to watch/The gentry fingering its stained tails./Whereupon ...Quietly, unopposed,/The motion was passed."[35]

In the Napoleonic Wars, the maximum number of lashes that could be inflicted on soldiers in the British Army reached 1,200. This many lashes could permanently disable or kill a man. Charles Oman, historian of the Peninsular War, noted that the maximum sentence was inflicted "nine or ten times by general court-martial during the whole six years of the war" and that 1,000 lashes were administered about 50 times.[36] Other sentences were for 900, 700, 500 and 300 lashes. One soldier was sentenced to 700 lashes for stealing a beehive.[37] Another man was let off after only 175 of 400 lashes, but spent three weeks in the hospital.[38] Later in the war, the more draconian punishments were abandoned and the offenders shipped to New South Wales instead, where more whippings often awaited them. (See Australian penal colonies section.) Oman later wrote:

If anything was calculated to brutalize an army it was the wicked cruelty of the British military punishment code, which Wellington to the end of his life supported. There is plenty of authority for the fact that the man who had once received his 500 lashes for a fault which was small, or which involved no moral guilt, was often turned thereby from a good soldier into a bad soldier, by losing his self-respect and having his sense of justice seared out. Good officers knew this well enough, and did their best to avoid the cat o' nine tails, and to try more rational means—more often than not with success.[39]

The 3rd battalion's Royal Anglian Regiment nickname of "The Steelbacks" is taken from one of its former regiments, the 48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot who earned the nickname for their stoicism when being flogged with the cat o' nine tails ("Not a whimper under the lash"), a routine method of administering punishment in the Army in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Shortly after the establishment of Northern Ireland the Special Powers Act of 1922 (known as the "Flogging Act") was enacted by the Parliament of Northern Ireland. The Act enabled the government to 'take all such steps and issue all such orders as may be necessary for preserving the peace and maintaining order'.[40] The long serving Home Affairs Minister Dawson Bates (1921–1943) was empowered to make any regulation felt necessary to preserve law and order. Breaking those regulations could bring a sentenced of up to a year in prison with hard labour, and in the case of some crimes, whipping.[41] This act was in place until 1973, when it was replaced with the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973. An imprisoned member of the Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), Frank Morris remembered his 15 "strokes of the cat" in 1942: "The pain was dreadful; you couldn't imagine it. The tail-ends cut my flesh to the bone, but I was determined not to scream and I didn't."[42]

The King's German Legion (KGL), which were German units in British pay, did not flog. In one case, a British soldier on detached duty with the KGL was sentenced to be flogged, but the German commander refused to carry out the punishment. When the British 73rd Foot flogged a man in occupied France in 1814, disgusted French citizens protested against it.[43]

France

editDuring the French Revolutionary Wars the French Army stopped floggings altogether,[43] inflicting death penalty or other severe corporal punishments instead.[44]

Australian penal colonies

editOnce common in the British Army and British Royal Navy as a means of discipline, flagellation also featured prominently in the British penal colonies in early colonial Australia. Given that convicts in Australia were already "imprisoned", punishments for offenses committed there could not usually result in imprisonment and thus usually consisted of corporal punishment such as hard labour or flagellation. Unlike Roman times, British law explicitly forbade the combination of corporal and capital punishment; thus, a convict was either flogged or hanged but never both.

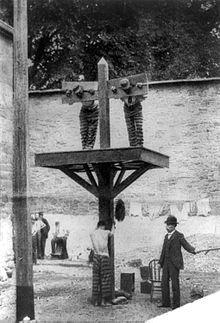

Flagellation took place either with a single whip or, more notoriously, with the cat o' nine tails. Typically, the offender's upper half was bared and he was suspended by the wrists beneath a tripod of wooden beams (known as 'the triangle'). In many cases, the offender's feet barely touched ground, which helped to stretch the skin taut and increase the damage inflicted by the whip. It also centered the offender's weight in his shoulders, further ensuring a painful experience.

With the prisoner thus stripped and bound, either one or two floggers administered the prescribed number of strokes, or "lashes," to the victim's back. During the flogging, a doctor or other medical worker was consulted at regular intervals as to the condition of the prisoner. In many cases, however, the physician merely observed the offender to determine whether he was conscious. If the prisoner passed out, the physician would order a halt until the prisoner was revived, and then the whipping would continue.

Female convicts were also subject to flogging as punishment, both on the convict ships and in the penal colonies. Although they were generally given fewer lashes than males (usually limited to 40 in each flogging), there was no other difference between the manner in which males and females were flogged.

Floggings of both male and female convicts were public, administered before the whole colony's company, assembled especially for the purpose. In addition to the infliction of pain, one of the principal purposes of the flogging was to humiliate the offender in front of his mates and to demonstrate, in a forceful way, that he had been required to submit to authority.

At the conclusion of the whipping, the prisoner's lacerated back was normally rinsed with brine, which served as a crude and painful disinfectant.

Flogging still continued for years after independence. The last person flogged in Australia was William John O'Meally in 1958 in Melbourne's Pentridge Prison.

As a religious practice

editAntiquity

editDuring the Ancient Roman festival of Lupercalia, young men ran through the streets with thongs cut from the hide of goats which had just been sacrificed, whipping people with the thongs as they ran. According to Plutarch, women would put themselves in their way to receive blows on the hands, believing that this would help them to conceive or grant them an easy delivery.[45] The eunuch priests of the goddess Cybele, the galli, flogged themselves until they bled during the annual festival called Dies Sanguinis.[46] The initiation ceremonies of Greco-Roman mystery religions also sometimes involved ritual flagellation, as did the Spartan cult of Artemis Orthia.[47]

Christianity

editThe Flagellation, in a Christian context, refers to an episode in the Passion of Christ prior to Jesus' crucifixion. The practice of mortification of the flesh for religious purposes has been utilised by members of various Christian denominations since the time of the Great Schism in 1054. Nowadays the instrument of penance is called a discipline, a cattail whip usually made of knotted cords, which is flung over the shoulders repeatedly during private prayer.[48]

In the 13th century, a group of Roman Catholics, known as the Flagellants, took self-mortification to an extreme, and would travel to towns and publicly beat and whip each other while preaching repentance. As these demonstrations by nature were quite morbid and disorderly, they were, during periods of time, suppressed by the authorities. They continued to reemerge at different times up until the 16th century.[49][50] Flagellation was also practised during the Black Plague as a means to purify oneself of sin and thus prevent contracting the disease. Pope Clement VI is known to have permitted it for this purpose in 1348,[51] but changed course, as he condemned the Flagellants as a cult the following year.[52]

Martin Luther, the Protestant Reformer, regularly practiced self-flagellation as a means of mortification of the flesh before leaving the Roman Catholic Church.[53] Likewise, the Congregationalist writer Sarah Osborn (1714–1796) also practiced self-flagellation in order "to remind her of her continued sin, depravity, and vileness in the eyes of God".[54] It became "quite common" for members of the Tractarian movement (see Oxford Movement, 1830s onwards) within the Anglican Communion to practice self-flagellation using the discipline.[55] St. Thérèse of Lisieux, a late 19th-century French Discalced Carmelite nun considered in Catholicism to be a Doctor of the Church, is an influential example of a saint who questioned prevailing attitudes toward physical penance. Her view was that loving acceptance of the many sufferings of daily life was pleasing to God, and fostered loving relationships with other people, more than taking upon oneself extraneous sufferings through instruments of penance. As a Carmelite nun, Saint Thérèse practiced voluntary corporal mortification.

Some members of strict monastic orders, and some members of the Catholic lay organization Opus Dei, practice mild self-flagellation using the discipline.[48] Pope John Paul II took the discipline regularly.[56] Self-flagellation remains common in Colombia, the Philippines, Mexico, Spain and one convent in Peru.[citation needed]

Shia Islam

editThis section should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (May 2022) |

As suffering and cutting the body with knives or chains (matam) have been prohibited by Shi'a marjas like Ali Khamenei, Supreme Leader of Iran,[57] some Shi'a observe mourning with blood donation which is called "Qame Zani"[57] and flailing.[58] Yet some Shi'ite men and boys continue to slash themselves with chains (zanjeer) or swords (talwar) and allow their blood to run freely.[58]

Certain rituals like the traditional flagellation ritual called Talwar zani (talwar ka matam or sometimes tatbir) using a sword or zanjeer zani or zanjeer matam, involving the use of a zanjeer (a chain with blades) are also performed.[59] These are religious customs that show solidarity with Husayn and his family. People mourn the fact that they were not present at the battle to fight and save Husayn and his family.[dubious – discuss][60][better source needed][61][better source needed] In some western cities, Shi'a communities have organized blood donation drives with organizations like the Red Cross on Ashura as a positive replacement for self-flagellation rituals like Tatbir and Qame Zani.

As a sexual practice

editFlagellation is also used as a sexual practice in the context of BDSM. The intensity of the beating is usually far less than used for punishment.

There are anecdotal reports of people willingly being bound or whipped, as a prelude to or substitute for sex, during the 14th century.[62] Flagellation practiced within an erotic setting has been recorded from at least the 1590s evidenced by a John Davies epigram,[63][64] and references to "flogging schools" in Thomas Shadwell's The Virtuoso (1676) and Tim Tell-Troth's Knavery of Astrology (1680).[65][66] Visual evidence such as mezzotints and print media in the 1600s is also identified revealing scenes of flagellation, such as in the late seventeenth-century English mezzotint "The Cully Flaug'd" from the British Museum collection.[65]

John Cleland's novel Fanny Hill, published in 1749, incorporates a flagellation scene between the character's protagonist Fanny Hill and Mr Barville.[67] A large number of flagellation publications followed, including Fashionable Lectures: Composed and Delivered with Birch Discipline (c. 1761), promoting the names of ladies offering the service in a lecture room with rods and cat o' nine tails.[68]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Three women among dozen publicly flogged in Afghanistan – Taliban official, by Mattea Bubalo, BBC News, 24 November 2022 Archived 24 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Houry, Nadim (16 December 2015). "If the Dead Could Speak". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Brutal torture in Syrian prison network detailed by New York Times investigation | CBC Radio". Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Documentation of 72 torture methods the Syrian regime continues to practice in its detention centers and military hospitals" (PDF). sn4hr.org. 21 October 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ "Syria: End Opposition Use of Torture, Executions". 17 September 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Rare Video Evidence of Torture in Syrian Hospitals". PBS. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Syria: Abuses in Kurdish-run Enclaves". 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Iraq: Chilling Accounts of Torture, Deaths". 19 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Smuggled video testimony documents harsh rule of Syrian Islamist group". TheGuardian.com. 19 February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Wilgenburg, Wladimir van (24 October 2017). "Secrets of the Black Stadium: In Raqqa, Inside ISIS' House of Horror". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Whipping". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 590–591.

- ^ "Crime and Justice – Punishment Sentences at the Old Bailey – Central Criminal Court". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ "Judicial and Prison Flogging and Whipping in Britain". www.corpun.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Country report for UK". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. June 2015.

- ^ Roudinesco, Elisabeth (1992). Madness and Revolution: The Lives and Legends of Theroigne de Mericourt, Verso. ISBN 0-86091-597-2. p. 198

- ^ Chapman, Tim (2001). Imperial Russia, 1801–1905 Archived 21 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 0-415-23110-8

- ^ "Saudi Arabia to end flogging as form of punishment: document". Reuters. 24 April 2020. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Martin, p. 76.

- ^ McKee, Christopher, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession The Creation of the U.S.Naval Officer Corps, 1794–1815, (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md.,1991), p. 243

- ^ McKee, p. 235

- ^ Sharp, John G.M., Flogging at Sea, Discipline and Punishment in the Old Navy http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/oldnavydiscipline.html Archived 23 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Parker, Hershel, Herman Melville A Biography Volume 1, 1819–1851 (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press 1996) p. 262

- ^ a b Hodak, George. "Congress Bans Maritime Flogging" Archived 22 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine. ABA Journal. September 1850, p. 72. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ 31st Congress, Session 1, Chapter 80 (1850), p. 515. Archived 11 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Quote: "Provided, That flogging in the navy, and on board vessels of commerce, be, and the same is hereby, abolished from and after the passage of this act."

- ^ "Sharp, John G.M. The Ship Log of the frigate USS United States 1843–1844 and Herman Melville Ordinary Seaman 2019, pp. 3–4 accessed 12 December 2020". www.usgwarchives.net. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Charles Roberts, editor, Journal of A Cruise to the Pacific Ocean, 1842–1844, in the Frigate United States With Notes on Herman Melville (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1937), p. 8.

- ^ Weigley, Russell (1984). History of the United States Army. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253203236.

- ^ Thomas Edward Murray; Thomas R. Murrell (1989). The Language of Sadomasochism: A Glossary and Linguistic Analysis. ABC-CLIO. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-313-26481-8. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "Life at sea in the age of sail Archived 27 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine". National Maritime Museum.

- ^ Tomasson, p. 127.

- ^ Underwood, Patrick, et al. "Threat, Deterrence, and Penal Severity: An Analysis of Flogging in the Royal Navy, 1740–1820." Social Science History, vol. 42, no. 3, 2018, pp. 411–439, JSTOR 90024188, Archived 27 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 27 December 2023

- ^ Knight, Rodger, The Pursuit of Victory The Life and Achievements of Horatio Nelson(Basic Books, New York, 2005), pp. 475–476

- ^ Sharp, John G.M., Americans on HMS Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar 21 Oct 1805, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/trafalgar.html Archived 21 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Keith Grint, The Arts of Leadership, 2000, ISBN 0191589330 pp. 237–238

- ^ Hughes, Ted, "Wilfred Owen's Photographs", Lupercal, 1960. See also Stanford, Jane, That Irishman: the Life and Times of John O'Connor Power, 2011, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Oman, p. 239.

- ^ Oman, p. 246.

- ^ Oman, p. 254.

- ^ Oman, p. 43.

- ^ McCluskey, Fergal, (2013), The Irish Revolution 1912–23: Tyrone, Four Courts Press, Dublin, p. 127, ISBN 9781846822995

- ^ McKenna, Fionnuala. "Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland), 1922". CAIN. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022. Paragraphs 4 and 5 of the Act.

- ^ Thorne, Kathleen (2019). Echoes of Their Footsteps Volume Three. Oregon: Generation Organization. p. 584. ISBN 978-0-692-04283-0.

- ^ a b Rothenberg, p. 179.

- ^ "... the infliction of corporal pain, without a Court-martial, and at the arbitrary will of the officers, did take place to a very great extent in the armies of Napoleon; in which, moreover, shooting was common to a degree that, he was persuaded, would astonish many hon. Gentlemen." Viscount Palmerston on Military flogging, Commons sitting, 02 April 1833 Archived 16 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Plutarch: The Life of Julius Caesar (section 61)". LacusCurtius. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Meyer, Marvin W. (1999). The Ancient Mysteries: A Sourcebook of Sacred Texts. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8122-1692-9. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Braunlein, Peter J. (2010). "Flagellation". In Melton, J. G.; Baumann, M. (eds.). Religions of the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 1119. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Opus Dei and corporal mortification". Opus dei. Opus Dei Information Office. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Flagellants". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "Flagellants". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 7 October 2018. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Leslie Alexander St. Lawrence Toke (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Aberth, John (2010). From the Brink of the Apocalypse: Confronting Famine, War, Plague and Death in the Later Middle Ages (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 144.

- ^ Wall, James T. The Boundless Frontier: America from Christopher Columbus to Abraham Lincoln. University Press of America. p. 103.

Though he did not go to the ends that had Luther—including even self-flagellation—the methods of ritualistic observance, self-denial, and good works did not satisfy.

- ^ Rubin, Julius H. (1994). Religious Melancholy and Protestant Experience in America. Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-19-508301-9.

In the many letters to her correspondents, Fish, Anthony, Hopkins, and Noyes, Osborn examined the state of her soul, sought spiritual guidance in the midst of her perplexities, and created a written forum for her continued self-examination. She cultivated an intense and abiding spirit of evangelical humiliation—self-flagellation and self-torture to remind her of her continued sin, depravity, and vileness in the eyes of God.

- ^ Yates, Nigel (1999). Anglican Ritualism in Victorian Britain, 1830–1910. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-19-826989-2.

Self-flagellation with a small scourge, known as a discipline, became quite common in Tractarian circles and was practised by Gladstone among others.

- ^ Barron, Fr. Robert (16 February 2010). "Taking the Discipline". YouTube. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021.

- ^ a b Akramulla Syed (20 February 2009). "Zanjeer Or Qama Zani on Ashura During Muharram". Ezsoftech.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Ashura observed with blood streams to mark Karbala tragedy". Jafariya News Network. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "Scars on the backs of the young". New Statesman. London. 6 June 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Bird, Steve (28 August 2008). "Devout Muslim guilty of making boys beat themselves during Shia ceremony". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 1 May 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ "British Muslim convicted over teen floggings". Alarabiya.net. 27 August 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Arne Hoffmann: In Leder gebunden. Der Sadomasochismus in der Weltliteratur, p. 11, Ubooks 2007, ISBN 978-3-86608-078-2 (German)

- ^ Epigram 33: "In Francum"

- ^ Bromley, James M. (1 May 2010). "Social Relations and Masochistic Sexual Practice in The Nice Valour". Modern Philology. 107 (4): 556–587. doi:10.1086/652428. ISSN 0026-8232. S2CID 144194164.

- ^ a b "British Printed Images to 1700: Print of the month". bpi1700.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Nomis, Anne O (2013) "Flogging Schools and Their Cullies" in The History & Arts of the Dominatrix, Mary Egan Publishing and Anna Nomis Ltd, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9927010-0-0 pp. 80–81

- ^ John Cleland: Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, Penguin Classics, (1986), ISBN 978-0-14-043249-7 pp. 180 ff

- ^ Fashionable Lectures Composed and Delivered with Birch Discipline (c. 1761) British Library Rare Books collection

Further reading

edit- Bean, Joseph W. Flogging, Greenery Press, 2000. ISBN 1-890159-27-1

- Bertram, James Glass. (1877 edition). Flagellation and the Flagellants: A History of the Rod. London: William Reeves.

- Conway, Andrew. The Bullwhip Book. Greenery Press, 2000. ISBN 1-890159-18-2

- Gibson, Ian. The English Vice: Beating, Sex and Shame in Victorian England and After. London: Duckworth, 1978. ISBN 0-7156-1264-6

- Martin, James Kirby; Lender, Mark Edward. A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763–1789. Arlington Heights, Ill.: Harlan Davidson, 1982. ISBN 0-88295-812-7

- Oman, Charles. Wellington's Army, 1809–1814. London: Greenhill, (1913) 1993. ISBN 0-947898-41-7

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1980). The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31076-8.

- Ricker, Kat. Doubting Thomas, Trillium Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-615-31849-3 Suspense thriller examining the dark nature of saintliness, including flagellation.

- Tomasson, Katherine & Buist, Francis. Battles of the '45. London: Pan Books, 1974.

External links

edit- Media related to Flagellation at Wikimedia Commons

- Video: Horrific footage shows man whipped with electrical cables

- Roots whipping scene of an enslaved person – Video

- Page about corporal punishment in the world

- "Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion" by Dr. Frederick Zugibe

- Pilot Guides – Flogging in penal Australia (including animation) Archived 13 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Information about a public punishment in Iran because alcohol and sex outside marriage

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Flagellation

- Suffering and Sainthood The importance of penance and mortification in the Catholic Church