In English contract law, an agreement establishes the first stage in the existence of a contract. The three main elements of contractual formation are whether there is (1) offer and acceptance (agreement) (2) consideration (3) an intention to be legally bound.

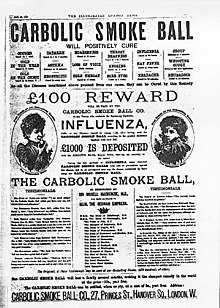

One of the most famous cases on forming a contract is Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company,[1] decided in nineteenth-century England. A medical firm advertised that its new wonder drug, a smoke ball, would cure people's flu, and if it did not, buyers would receive £100. When sued, Carbolic argued the ad was not to be taken as a serious, legally binding offer. It was merely an invitation to treat, and a gimmick. But the court of appeal held that it would appear to a reasonable man that Carbolic had made a serious offer. People had given good "consideration" for it by going to the "distinct inconvenience" of using a faulty product. "Read the advertisement how you will, and twist it about as you will," said Lindley LJ, "here is a distinct promise expressed in language which is perfectly unmistakable".

Offer

editThe most important feature of a contract is that one party makes an offer for a bargain that another accepts. This can be called a 'concurrence of wills' or a 'meeting of the minds' of two or more parties. There must be evidence that the parties had each from an objective perspective engaged in conduct manifesting their assent, and a contract will be formed when the parties have met such a requirement.[2] An objective perspective means that it is only necessary that somebody gives the impression of offering or accepting contractual terms in the eyes of a reasonable person, not that they actually did want to contract.[3]

Invitations to treat

editWhere a product in large quantities is advertised for in a newspaper or on a poster, it is generally regarded as an offer, however if the person who is to buy the advertised product is of importance, i.e. his personality etc., when buying e.g. land, it is merely an invitation to treat. In Carbolic Smoke Ball, the major difference was that a reward was included in the advertisement which is a general exception to the rule and is then treated as an offer. Whether something is classified as an offer or an invitation to treat depends on the type of agreement being made and the nature of the sale. In retail situations an item being present is normally considered an invitation to treat; this was established for items on display in shop windows in Fisher v Bell [1961] 1 QB 394 and for items on shelves in Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd [1953] 1 QB 401.

Retail agreements can also be considered invitations to treat if there is simply not enough information in the initial statement for it to constitute an offer.[4] In Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 1 WLR 1204 the defendant had placed an advertisement indicating that he had certain birds for sale, giving a price but no information about quantities. He was arrested under the Protection of Birds Act 1954 for 'offering such birds for sale'; it was ruled that since the advertisement did not specify the number of birds he had it could not constitute an offer; if it did he could have been legally bound to provide more birds than he possessed.[4] The same principle was applied for catalogues in Grainger v Gough [1896] AC 325, when it was ruled that posting catalogues of items for sale to people did not constitute an offer since there was insufficient detail.[4]

- Chapelton v Barry UDC

- Spencer v Harding (1870) LR 5 CP 561

- Harvey v Facey [1893] AC 552

Offers generally

edit- Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. [1893] 1 QB 256

Auctions

edit- Warlow v Harrison (1859) 1 E & E 309; 120 ER 925

- Harris v Nickerson

- Payne v Cave

- Barry v Davies (t/a Heathcote Ball & Co) [2001] 1 All ER 944

- Sale of Goods Act 1979, s 57(2)

Termination of offer

editRevocation

edit- Routledge v Grant (1828) 4 Bing 653; 130 ER 920: Grant offered to buy Routledge’s house, and laid down a requirement that his offer had to be accepted within six weeks. During that period he withdrew the offer. The court held that "the offeror was entitled to revoke his offer at any time prior to acceptance because no option agreement existed",[5] which would have obliged Grant to keep the offer open.

- Byrne v Van Tienhoven (1880) 5 CPD 344

- Dickinson v Dodds [1876] 2 Ch D 463

- Errington v Errington [1952] 1 KB 290

Rejection

editAn offer can be rejected by the offeree(s). An offer which is rejected is thereby extinguished: see Hyde v Wrench (1840) 3 Bea 334.

Lapse of time

editWhen an offer is stated to be open for a specific length of time, the offer automatically terminates when it exceeds the time limit. See:

- Ramsgate Victoria Hotel v Montefiore (1866) LR 1 11 Ex 109

- Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial Investments Ltd

Death

edit- In Bradbury et al. v Morgan et al. (1862),[6] the court ruled that a death does not in general operate to revoke a contract, although in exceptional cases it will do so.[7]

Counter offers

edit- Hyde v Wrench (1840) 3 Bea 334

- Stevenson, Jacques & Co v McLean (1880) 5 QBD 346

Acceptance

editAcceptance by conduct

edit- Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co (1877) 2 App Cas 666

Prescribed method of acceptance

edit- Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial Investments Ltd [1969] 3 All ER 1593

Knowledge and reliance on offer

edit- Williams v Carwardine (1833) 5 C & P 566; 172 ER 1101

- Gibbons v Proctor

- R v Clarke (1927) 40 CLR 227

Cross offers

editA writes to B offering to sell certain property at a stated price. B writes to A offering to buy the same property at the same price. The letters cross in the post. Is there (a) an offer and acceptance, (b) a contract?

In this case, it is assumed that "where offers cross there was no binding contract", because B's acceptance was not communicated to A. Therefore, there was no contract what so ever.

- Tinn v Hoffman (1873) 29 LT 271: "A rejection terminates an offer, so that it can no longer be accepted." The authority cited in Bonner Properties Ltd v McGurran Construction Ltd, a Northern Ireland case of 2008, is Tinn v Hoffman and Company (1873):

In that case Mr Tinn was negotiating with the defendants for the purchase of some 800 tons of iron. The exchange of correspondence between them dealt with quantity, time and price. The majority of the Court of Exchequer held that there was no binding contract as the plaintiff's purported letter of acceptance of 28 November did not constitute the same as it was too late for the defendant's offer to sell contained in the letter of 24 November (which had requested "your reply by return of post"). On appeal to the Court of Exchequer Chamber the majority of that court (Blackburn, Keating, Brett, Grove and Archibald JJ, with Quain and Honeyman JJ dissenting) affirmed this judgment of the majority below.[8]

Battle of the forms

edit- Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-cello Cpn (England) Ltd [1979] 1 WLR 401

Acceptance in case of tenders

edit- Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Co of Canada [1986] AC 207

- Blackpool & Fylde Aero Club v Blackpool Borough Council [1990] 1 WLR 1195

Communication of acceptance

editNecessity for communication

editWaiver

editSilence a condition of acceptance

edit- Felthouse v Bindley (1862) 11 CBNS 869

- Consumer Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000 (SI 2000/2334) Reg 24

Post or telegram

edit- Adams v Lindsell [1818] EWHC KB J59

- Henthorn v Fraser [1892] 2 Ch 27

- Holwell Securities Ltd v. Hughes [1974] 1 WLR 155

Telex

edit- Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corporation [1955] 2 QB 327

- Brinkibon Ltd v. Stahag Stahl mbH [1983] 2 AC 34

- The Brimnes [1975] QB 929

Revocation of Acceptance

editRevocation can be made by the offeror only before acceptance is made. Also the revocation must be communicated to the offeree(s).Unless and until the revocation is communicated, it is ineffective. See:

- Byrne v Van Tienhoven (1880) 5 CPD 344.

- Hudson ‘Retraction of Letters of Acceptance’ (1966) 82 Law Quarterly Review 169

Certainty and completeness

editIf the terms of the contract are uncertain or incomplete, the parties cannot have reached an agreement in the eyes of the law.[9] An agreement to agree does not constitute a contract, and an inability to agree on key issues, which may include such things as price or safety, may cause the entire contract to fail. However, a court will attempt to give effect to commercial contracts where possible, by construing a reasonable construction of the contract (Hillas and Co Ltd v Arcos Ltd[10]).

Courts may also look to external standards, which are either mentioned explicitly in the contract[11] or implied by common practice in a certain field.[12] In addition, the court may also imply a term; if price is excluded, the court may imply a reasonable price, with the exception of land, and second-hand goods, which are unique.

If there are uncertain or incomplete clauses in the contract, and all options in resolving its true meaning have failed, it may be possible to sever and void just those affected clauses if the contract includes a severability clause. The test of whether a clause is severable is an objective test—whether a reasonable person would see the contract standing even without the clauses.

- Sale of Goods Act 1979 ss 8(2) 9

See also

edit- English tort law

- Consideration in English law

- Powell v Lee (1908) 99 LT 284

Notes

edit- ^ Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1893] 2 QB 256

- ^ e.g. Lord Steyn, Contract Law: Fulfilling the Reasonable Expectations of Honest Men (1997) 113 LQR 433; c.f. § 133 BGB in Germany, where "the actual will of the contracting party, not the literal sense of words, is to be determined"

- ^ Smith v Hughes

- ^ a b c Poole (2004) p.40

- ^ Keenan, A. (2012), Essentials of Irish Business Law, 6th edition, chapter 10, p 94, accessed 25 May 2021

- ^ 1 H & C 249; 158 ER 877

- ^ All Answers Ltd., Bradbury v Morgan (1862) 158 ER 877, accessed 23 April 2018

- ^ High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland, Chancery Division, Bonner Properties Ltd v McGurran Construction Ltd, NICh 16, delivered 26 November 2008, accessed 16 August 2023

- ^ Fry v Barnes (1953) 2 DLR 817 (BCSC)

- ^ (1932) 147 LT 503

- ^ Whitlock v Brew (1968) 118 CLR 445

- ^ Three Rivers Trading Co Ltd v Gwinear & District Farmers Ltd (1967) 111 Sol J 831