Russian Americans (Russian: русские американцы, romanized: russkiye amerikantsy, IPA: [ˈruskʲɪje ɐmʲɪrʲɪˈkant͡sɨ]) are Americans of full or partial Russian ancestry. The term can apply to recent Russian immigrants to the United States, as well as to those who settled in the 19th-century Russian possessions in northwestern America. Russian Americans comprise the largest Eastern European and East Slavic population in the US, the second-largest Slavic population generally, the nineteenth-largest ancestry group overall, and the eleventh-largest from Europe.[3]

Русские американцы (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 2,432,733 self-reported[1] 0.741% of the U.S. population (2019) 391,641 Russian-born[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| Languages | |

| American English, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Eastern Orthodoxy (Russian Orthodox Church, Orthodox Church in America) Minority: Old Believers (Russian Orthodox Old-Rite Church), Catholic Church (Russian Greek Catholic Church), Protestantism, Judaism, Shamanism, Tengrism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Belarusian Americans, Rusyn Americans, Ukrainian Americans, Russian Jews, Alaskan Creoles |

In the mid-19th century, waves of Russian immigrants fleeing religious persecution settled in the US, including Russian Jews and Spiritual Christians. From 1880 to 1917, within the wave of European immigration to the US that occurred during that period, a large number of Russians immigrated primarily for economic opportunities. These groups mainly settled in coastal cities, including Brooklyn (New York City) on the East Coast, and Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Oregon, and various cities in Alaska, on the West Coast, as well as in Great Lakes cities, such as Chicago and Cleveland. After the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922, many White émigrés also arrived, especially in New York, Philadelphia, and New England. Emigration from Russia subsequently became very restricted during the Soviet era (1917–1991). However, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War, immigration to the United States increased considerably.

In several major US cities, many Jewish Americans who trace their heritage back to Russia and other Americans of East Slavic origin, such as Belarusian Americans and Rusyn Americans, sometimes identify as Russian Americans. Additionally, certain non-Slavic groups from the post-Soviet space, such as Armenian Americans, Georgian Americans, and Moldovan Americans, have a longstanding historical association with the Russian American community.

Demographics

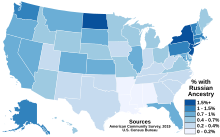

editAccording to the Institute of Modern Russia in 2011, the Russian American population is estimated to be 3.13 million.[4] The American Community Survey of the US census shows the total number of people in the US age 5 and over speaking Russian at home to be slightly over 900,000, as of 2020.

Many Russian Americans do not speak Russian,[5] having been born in the United States and brought up in English-speaking homes. In 2007, however, Russian was the primary spoken language of 851,174 Americans at home, according to the US census.[4] According to the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University, 750,000 Russian Americans were ethnic Russians in 1990.[6]

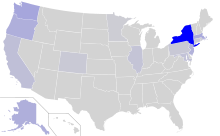

The New York City metropolitan area has historically been the leading metropolitan gateway for Russian immigrants legally admitted into the United States.[7] Brighton Beach, Brooklyn continues to be the most important demographic and cultural center for the Russian American experience. However, as Russian Americans have climbed in socioeconomic status, the diaspora from Russia and other former Soviet-bloc states has moved toward more affluent parts of the New York metropolitan area, notably Bergen County, New Jersey. Within Bergen County, the increasing size of the Russian immigrant presence in its hub of Fair Lawn prompted a 2014 April Fool's satire titled, "Putin Moves Against Fair Lawn".[8]

Sometimes, Carpatho-Rusyns and Ukrainians who emigrated from Carpathian Ruthenia in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century identify as Russian Americans. More recent émigrés would often refer to this group as the starozhili 'old residents'. This group became the pillar of the Russian Orthodox Church in America.[citation needed] Today, most of this group has become assimilated into the local society, with ethnic traditions continuing to survive primarily around the church.

Russian-born population

editRussian-born population in the US since 2010:[9][2]

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 383,166 |

| 2011 | 399,216 |

| 2012 | 399,128 |

| 2013 | 390,934 |

| 2014 | 390,977 |

| 2015 | 386,529 |

| 2016 | 397,236 |

| 2017 | 403,670 |

| 2018 | 391,094 |

| 2019 | 391,641 |

Social status

editThe median household income in 2017 for Americans of Russian descent is estimated by the US census as $80,554.[10]

| Ethnicity | Household Income | College degrees (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Russian | $80,554 | 60.4 |

| Polish | $73,452 | 42.5 |

| Czech | $71,663 | 45.4 |

| Serbian | $79,135 | 46.0 |

| Slovak | $73,093 | 44.8 |

| Ukrainian | $75,674 | 52.2 |

| White non-Hispanic | $65,845 | 35.8 |

| Total US population | $60,336 | 32.0 |

History

editColonial era

editRussian America (1733–1867)

editThe territory that today is the US state of Alaska was settled by Russians and controlled by the Russian Empire; Russian settlers include ethnic Russians but also Russified Ukrainians, Russified Romanians (from Bessarabia), and Indigenous Siberians,[citation needed] including Yupik, Mongolic peoples, Chukchi, Koryaks, Itelmens, and Ainu. Georg Anton Schäffer of the Russian-American Company built three forts in Kauai, Hawaii. The southernmost such post of the Russian-American Company was Fort Ross, established in 1812 by Ivan Kuskov, some 50 miles (80 km) north of San Francisco, as an agricultural supply base for Russian America. It was part of the Russian-America Company, and consisted of four outposts, including Bodega Bay, the Russian River, and the Farallon Islands. There was never an established agreement made with the government of New Spain which produced great tension between the two countries. Spain claimed the land but had never established a colony there. The well-armed Russian fort prevented Spain from removing the Russians living there. Without the Russians' hospitality, the Spanish colony would have been abandoned because their supplies had been lost when Spanish supply ships sank in a large storm off the South American coast. After the independence of Mexico, tensions were reduced and trade was established with the new government of Mexican California.

Russian America was not a profitable colony because of high transportation costs and the declining animal population. After it was purchased by the United States in 1867, most Russian settlers went back to Russia, but some resettled in southern Alaska and California. Included in these were the first miners and merchants of the California gold rush.[citation needed] All descendants of Russian settlers from Russian Empire, including mixed-race with partial Alaska Native blood, totally assimilated to the American society. Most Russians in Alaska today are descendants of Russian settlers who came just before, during, and/or after Soviet era; two thirds of the population of town of Alaska named Nikolaevsk are descendants of recent Russian settlers who came in the 1960s.

Immigration to the US

editFirst wave (1870–1915)

editThe first massive wave of immigration from all areas of Europe to the United States took place in the late 19th century. Although some immigration took place earlier – the most notable example being Ivan Turchaninov, who immigrated in 1856 and became a United States Army brigadier general during the Civil War– millions traveled to the new world in the last decade of the 19th century, some for political reasons, some for economic reasons, and some for a combination of both. Between 1820 and 1870 only 7,550 Russians immigrated to the United States, but starting with 1881, immigration rate exceeded 10,000 a year: 593,700 in 1891–1900, 1.6 million in 1901–1910, 868,000 in 1911–1914, and 43,000 in 1915–1917.[11]

The most prominent Russian groups that immigrated in this period were groups from Imperial Russia seeking freedom from religious persecution. These included Russian Jews, escaping the 1881–1882 pogroms, who moved to New York City and other coastal cities; the Spiritual Christians, treated as heretics at home, who settled largely in the Western United States in the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco,[11][12] and Portland, Oregon;[13] two large groups of Shtundists who moved to Virginia and the Dakotas,[11] and mostly between 1874 and 1880 German-speaking Anabaptists, Russian Mennonites and Hutterites, who left the Russian Empire and settled mainly in Kansas (Mennonites), the Dakota Territory, and Montana (Hutterites). Finally in 1908–1910, the Old Believers, persecuted as schismatics, arrived and settled in small groups in California, Oregon (particularly the Willamette Valley region),[13] Pennsylvania, and New York.[11] Immigrants of this wave include Irving Berlin, legend of American songwriting and André Tchelistcheff, influential Californian winemaker.

World War I dealt a heavy blow to Russia. Between 1914 and 1918, starvation and poverty increased in all parts of Russian society, and soon many Russians questioned the War's purpose and the government's competency. The war intensified anti-Semitic sentiment. Jews were accused of disloyalty and expelled from areas in and near war zones. Furthermore, much of the fighting between Russia, and Austria and Germany took place in Western Russia in the Jewish Pale of Settlement. World War I uprooted half a million Russian Jews.[14] Because of the upheavals of World War I, immigration dwindled between 1914 and 1917. But after the war, hundreds of thousands of Jews began leaving Europe and Russia again for the US, modern-day Israel and other countries where they hoped to start a new life.[15]

Second wave (1916–1922)

editA large wave of Russians immigrated in the short time period of 1917–1922, in the wake of October Revolution and Russian Civil War. This group is known collectively as the White émigrés. The US was the third largest destination for those immigrants, after France and Serbia.[citation needed] This wave is often referred to as the first wave, when discussing Soviet era immigration. The head of the Russian Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky, was one of those immigrants.

Since the immigrants were of the higher classes of the Russian Empire, they contributed significantly to American science and culture. Inventors Vladimir Zworykin, often referred to as "father of television", Alexander M. Poniatoff, the founder of Ampex, and Alexander Lodygin, arrived with this wave. The US military benefited greatly with the arrival of such inventors as Igor Sikorsky (who invented the practical Helicopter), Vladimir Yourkevitch, and Alexander Procofieff de Seversky. Sergei Rachmaninoff and Igor Stravinsky are by many considered to be among the greatest composers ever to live in the United States of America. The novelist Vladimir Nabokov, the violinist Jasha Heifetz, and the actor Yul Brynner also left Russia in this period.

As with first and second wave, if the White émigré left Russia to any country, they were still considered first or second wave, even if they ended up moving to another country, including the US at a later time. There was no 'strict' year boundaries, but a guideline to have a better understanding of the time period. Thus, 1917-1922 is a guideline. There are Russians who are considered second wave even if they arrived after 1922 up to 1948.

Soviet era (1922–1991)

editDuring the Soviet era, emigration was prohibited, and limited to very few defectors and dissidents who immigrated to the United States of America and other Western Bloc countries for political reasons. Immigration to the US from Russia was also severely restricted via the National Origins formula introduced by the US Congress in 1921. The chaos and depression that plagued Europe following the conclusion of World War II drove many native Europeans to immigrate to the United States. After the war, there were about 7 million displaced persons ranging from various countries throughout continental Europe.[16] Of these 7 million, 2 million were Russian citizens that were sent back to the USSR to be imprisoned, exiled, or even executed having been accused of going against their government and country.[17] Roughly 20,000 Russian citizens immigrated to the United States immediately following the conclusion of the war.[18] Following the war, tensions between the United States and the then Soviet Union began to rise to lead to the USSR placing an immigration ban on its citizens in 1952.[18] The immigration ban effectively prevented any citizen or person under the USSR from immigrating to the United States. This came after a large percentage of Russian immigrants left for the United States specifically leaving the USSR embarrassed at the high percentage of Russian citizens emigrating. After the immigration ban was placed into effect, any Russian citizen that attempted to or planned to leave Russia was stripped of citizenship, barred from having any contact with any remaining relatives in the USSR, and would even make it illegal for that individual's name to be spoken.[19] Some fled the Communist regime, such as Vladimir Horowitz in 1925 or Ayn Rand in 1926, or were deported by it, such as Joseph Brodsky in 1972, or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in 1974, some were communists themselves, and left in fear of prosecution, such as NKVD operative Alexander Orlov who escaped the purge in 1938[20] or Svetlana Alliluyeva, daughter of Joseph Stalin, who left in 1967. Some were diplomats and military personnel who defected to sell their knowledge, such as the pilots Viktor Belenko in 1976 and Aleksandr Zuyev in 1989.

Following the international condemnation of the Soviet reaction to Dymshits–Kuznetsov hijacking affair in 1970, the Soviet Union temporarily loosened emigration restrictions for Jewish emigrants, which allowed nearly 250,000 people leave the country,[21] escaping covert antisemitism. Some went to Israel, especially at the beginning, but most chose the US as their destination, where they received the status of political refugees. This lasted for about a decade, until very early 1980s. Emigrants included the family of Google co-founder Sergey Brin, which moved to the US in 1979, citing the impossibility of an advanced scientific career for a Jew.[citation needed] By the 1970s, relations between the USSR and the United States began to improve and the USSR relaxed its emigration ban, permitting a few thousand citizens to emigrate to the United States.[18] However, just as had happened 20 years prior, the USSR saw hundreds of thousands of its citizens emigrate to the United States during the 1970s.[18] The Soviet Union then created the "diploma tax" which charged any person that had studied in Russia and was trying to emigrate a hefty fine. This was mainly done to deter Soviet Jews who tended to be scientists and other valued intellects from emigrating to Israel or the West.[16] Due to the USSR suppressing its citizens from fleeing the USSR, the United States passed the Jackson-Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974. The amendment stipulated that the United States would review the record of human rights before permitting any special trade agreements with countries with non-market economies.[22] As a result, the USSR was pressured into allowing those citizens that wanted to flee the USSR for the United States to do so, with a cap on the number of citizens allowed to leave per year.[23] The Jackson-Vanik amendment made it possible for the religious minorities of the USSR such as Roman-Catholics, Evangelical Christians, and Jews to emigrate to the United States.[18] It effectively kept emigration from the USSR to the United States open and as a result, from 1980 to 2008 some 1 million people emigrated from the former Soviet Union to the United States.[18]

The 1970s witnessed 51,000 Soviet Jews emigrate to the United States, a majority after the Trade Agreement of 1974 was passed.[22] The majority of the Soviet Jews that emigrated to the United States went to Cleveland.[22] Here, chain migration began to unfold as more Soviet Jews emigrated after the 1970s, concentrating in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland.[22] The majority of Soviet Jews that had arrived were educated and held college degrees.[22] These new immigrants would go onto work in important industrial businesses in the city such as BP America and General Electric Co. Other Russian and later post-Soviet immigrants found work in the Cleveland Orchestra or the Cleveland Institute of Music as professional musicians and singers.[22][24]

The slow Brezhnev stagnation of the 1970s and Mikhail Gorbachev's following political reforms since the mid-1980s prompted an increase of economic immigration to the United States, where artists and athletes defected or legally emigrated to the US to further their careers: ballet stars Mikhail Baryshnikov in 1974 and Alexander Godunov in 1979, composer Maxim Shostakovich in 1981, hockey star Alexander Mogilny in 1989 and the entire Russian Five later, gymnast Vladimir Artemov in 1990, glam metal band Gorky Park in 1987, and many others.

Post-Soviet era (1991–present)

edit| Year | Speakers |

|---|---|

| 1910a | 57,926 |

| 1920a | 392,049 |

| 1930a | 315,721 |

| 1940a | 356,940 |

| 1960a | 276,834 |

| 1970a | 149,277 |

| 1980[25] | 173,226 |

| 1990[26] | 241,798 |

| 2000[27] | 706,242 |

| 2011[28] | 905,843 |

| ^a Foreign-born population only[29] | |

With perestroika, a mass Jewish emigration restarted in 1987. The numbers grew very sharply, leading to the United States forbidding entry to those emigrating from the USSR on Israeli visa, starting October 1, 1989. Israel withheld sending visa invitations from the beginning of 1989 claiming technical difficulties. After that the bulk of Jewish emigration went to Israel, nearing a million people in the following decade. However, the conditions for Soviet refugees belonging to several religious minorities - including Jews, Baptists, Pentecostalists, and Greek Catholics - were eased by the Lautenberg Amendment passed in 1989 and renewed annually. Those who could claim family reunion could apply for the direct US visa, and were still receiving the political refugee status in the early 1990s. 50,716 citizens of ex-USSR were granted political refugee status by the United States in 1990, 38,661 in 1991, 61,298 in 1992, 48,627 in 1993, 43,470 in 1994, 35,716 in 1995[30] with the trend steadily dropping to as low as 1,394 refugees accepted in 2003.[31] For the first time in history, Russians became a notable part of illegal immigration to the United States.

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent transition to free market economy came hyperinflation and a series of political and economic crises of the 1990s, culminating in the financial crash of 1998. By mid-1993 between 39% and 49% of Russians were living in poverty, a sharp increase compared to 1.5% of the late Soviet era.[32] This instability and bleak outcome prompted a large new wave of both political and economic emigration from Russia, and one of the major targets became the United States, which was experiencing an unprecedented stock market boom in 1995–2001.

A notable part of the 1991—2001 immigration wave consisted of scientists and engineers who, faced with extremely poor job market at home[33] coupled with the government unwilling to index fixed salaries according to inflation or even to make salary payments on time, left to pursue their careers abroad. This coincided with the surge of hi-tech industry in the United States, creating a strong brain drain effect. According to the National Science Foundation, there were 20,000 Russian scientists working in the United States in 2003,[34] and the Russian software engineers were responsible for 30% of Microsoft products in 2002.[33] Skilled professionals often command a significantly higher wage in the US than in Russia.[35] The number of Russian migrants with university educations is higher than that of US natives and other foreign born groups.[36]

51% of lawful Russian migrants obtain permanent residence from immediate family member of US citizens, 20% obtain it from the Diversity Lottery, 18% obtain it through employment, 6% are family sponsored, and 5% are refugee and asylum seekers.[37]

The Soviet Union was a sports empire, and many prominent Russian sportspeople found great acclaim and rewards for their skills in the United States. Examples are Anna Kournikova, Maria Sharapova, Alexander Ovechkin, Alexandre Volchkov, and Andrei Kirilenko. Nastia Liukin was born in Moscow, but came to America with her parents as a young child, and developed as a champion gymnast in the US.

On 27 September 2022, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre encouraged Russian men fleeing their home country to avoid being drafted to apply for asylum in the United States.[38] In early 2023, the Biden administration resumed deportations of Russians who had fled Russia due to mobilization and political persecution.[39]

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the persecution of Russian citizens who disagree with the policies of Russian leader Vladimir Putin has increased significantly. For example, in early 2024, ballet dancer Ksenia Karelina, a dual American-Russian citizen and resident of Los Angeles, was arrested while visiting family in Russia and charged with treason for sending $51.80 to Razom, a New York City-based nonprofit organization that sends humanitarian assistance to Ukraine.[40] She initially faced life in prison, but pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 years in prison.[41] In July 2024, Russian-American journalist Alsu Kurmasheva was sentenced to 6.5 years in prison for spreading "false information" about Russia's military operations in Ukraine.[42]

Notable communities

editCommunities with high percentages of people of Russian ancestry

The top US communities with the highest percentage of people claiming Russian ancestry are:[43]

- Fox River, Alaska 80.9%[44]

- Aleneva, Alaska 72.5%[45]

- Nikolaevsk, Alaska 67.5%[46]

- Pikesville, Maryland 19.30%

- Roslyn Estates, New York 18.60%

- Hewlett Harbor, New York 18.40%

- East Hills, New York 18.00%

- Wishek, North Dakota 17.40%

- Eureka, South Dakota 17.30%

- Beachwood, Ohio 16.80%

- Penn Wynne, Pennsylvania 16.70%

- Kensington, New York and Mayfield, Pennsylvania 16.20%

- Napoleon, North Dakota 15.80%

US communities with the most residents born in Russia

Top US communities with the most residents born in Russia are:[47]

- Millville, Delaware 8.5%

- South Windham, Maine 7.8%

- South Gull Lake, Michigan 7.6%

- Loveland Park, Ohio 6.8%

- Terramuggus, Connecticut 4.7%

- Harwich Port, Massachusetts 4.6%

- Brush Prairie, Washington 4.5%

- Feasterville, Pennsylvania 4.4%

- Colville, Washington 4.4%

- Mayfield, Ohio 4.0%

- Serenada, Texas 4.0%

- Orchards, Washington 3.6%

- Leavenworth, Washington 3.4%

Apart from such settlements as Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, concentrations of Russian Americans can be found in Bergen County, New Jersey; Queens; Staten Island; Anchorage, Alaska; Baltimore; Boston; The Bronx; other parts of Brooklyn; Chicago; Cleveland; Detroit; Los Angeles; Beverly Hills; Miami; Milwaukee; Minneapolis; Palm Beach; Houston; Dallas; Orlando; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Portland, Oregon;[48] Sacramento; San Francisco; Raleigh and Research Triangle Region North Carolina, and Seattle.

Notable people

editSee also

edit- Russian language in the United States

- History of the Russians in Baltimore

- Slavic Voice of America

- St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral

- Florida Russian Lifestyle Magazine

- AmBAR – American Business Association of Russian Professionals

- American Chamber of Commerce in Russia

- Category:Russian communities in the United States

- Russian colonization of the Americas

- Russian American Medical Association

- Brighton Ballet Theater

- Russian Canadian

- Russia–United States relations

- Russian Americans in New York City

- Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia

- Orthodox Church in America (formerly North American Russian Metropolia)

References

edit- ^ "Table B04006 - PEOPLE REPORTING ANCESTRY - 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Table B05006 - PLACE OF BIRTH FOR THE FOREIGN-BORN POPULATION IN THE UNITED STATES - 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "Largest Ethnic Groups and Nationalities in US". World Atlas. July 18, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "Rediscovering Russian America". Institute of Modern Russia. 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "Growing Up Russian". Aleksandr Strezev, Principia. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ "Immigration: Russia. Curriculum for Grade 6–12 Teachers". Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2013". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Matt Rooney (April 1, 2014). "Putin Moves Against Fair Lawn". Save Jersey. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

In a move certain to carry dire geopolitical consequences for the world, the Russian Federation has moved troops into the 32,000-person borough of Fair Lawn, New Jersey, only days after annexing Crimea and strengthening its troop positions along the Ukrainian border.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Nitoburg, E. (1999). Русские религиозные сектанты и староверы в США. Новая И Новейшая История (in Russian) (3): 34–51. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ Chapter 1 – The Migration in Dukh-i-zhizniki In America by Andrei Conovaloff, 2018 (in-progress)

- ^ a b "Russians and East Europeans in America". Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ Gitelman, Zvi. A Century of Ambivalence, The Jews of Russia and the Soviet Union, 1881 to the Present. 2nd Ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988. Print.

- ^ Barnarvi, Eli ed. A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People. New York: Schocken Books, 1992. Print.

- ^ a b Moh, Caroline. "The Jackson-Vanik Amendment and U.S.-Russian Relations". wilsoncenter.org.

- ^ "Russians and East Europeans in America". sites.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Soviet Exiles | Polish/Russian | Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "Soviet Exiles | Polish/Russian | Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History | Classroom Materials | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Trahair, R. C. S. (2004). Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-0-313-31955-6. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ History of Dissident Movement in the USSR by Lyudmila Alexeyeva. Vilnius, 1992 (in Russian)

- ^ a b c d e f Shaland, Irene. "Soviet and Post-Soviet Immigration". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ "Cypress & Spruce". Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "Russians". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ "Appendix Table 2. Languages Spoken at Home: 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2007". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Detailed Language Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for Persons 5 Years and Over --50 Languages with Greatest Number of Speakers: United States 1990". United States Census Bureau. 1990. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "Language Spoken at Home: 2000". United States Bureau of the Census. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Language Use in the United States: 2011" (PDF). United States Bureau of the Census. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "Mother Tongue of the Foreign-Born Population: 1910 to 1940, 1960, and 1970". United States Census Bureau. March 9, 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Fiscal Year 1999 Statistical Yearbook" (PDF). Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ^ "Refugees and Asylees: 2005" (PDF). Department of Homeland Security Office of Immigration Statistics. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ^ Branko Milanovic, Income, Inequality, and Poverty During the Transformation from Planned to Market Economy (Washington DC: The World Bank, 1998), pp.186–90.

- ^ a b "Russian brain drain tops half a million". BBC. June 20, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "Утечка мозгов" – болезнь не только российская. Экология И Жизнь (in Russian). 2003. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "Russian brain drain tops half a million". June 20, 2002. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ "Census 2000 Foreign-Born Profiles". www.census.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ "Table 10. Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status By Broad Class Of Admission And Region And Country Of Birth: Fiscal Year 2016". Department of Homeland Security. May 16, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ "The White House told Russians to flee here instead of fighting Ukraine. Then the U.S. tried to deport them". Los Angeles Times. August 17, 2023.

- ^ "Biden administration quietly resumes deportations to Russia". The Guardian. March 18, 2023.

- ^ Stapleton, Ivana Kottasová, AnneClaire (August 7, 2024). "Russian-American woman admits guilt in treason case, Russian state media reports". CNN. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ksenia Karelina: US-Russian woman jailed in Russia for 12 years for treason". www.bbc.com. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ "Russian-American journalist jailed by Moscow for six-and-a-half years". The Guardian. July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Ancestry Map of Russian Communities". Epodunk.com. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml# [1] American fact finder, Fox River, Alaska, Census 2000-Selected Social Characteristics (Household and Family Type, Disability, Citizenship, Ancestry, Language, ...)

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml# [2] American fact finder, Aleneva, Alaska, Census 2000-Selected Social Characteristics (Household and Family Type, Disability, Citizenship, Ancestry, Language, ...)

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml# [3] American fact finder, Nikolaevsk, Alaska, Census 2000-Selected Social Characteristics (Household and Family Type, Disability, Citizenship, Ancestry, Language, ...)

- ^ "Top 101 cities with the most residents born in Russia (population 500+)". City-Data. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Greenstone, Scott (June 16, 2016). "Oregon's Soviet Diaspora: 25 Years Later, The Refugee Community Wants To Be Known". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Eubank, Nancy. The Russians in America (Lerner Publications, 1979).

- Hardwick, Susan Wiley. Russian Refuge: Religion, Migration, and Settlement on the North American Pacific Rim (U of Chicago Press, 1993).

- Jacobs, Dan N., and Ellen Frankel Paul, eds. Studies of the Third Wave: Recent Migration of Soviet Jews to the United States (Westview Press, 1981).

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. "Russian Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 4, Gale, 2014), pp. 31–45. online

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. The Russian Americans (Chelsea House, 1989).

External links

edit- "Russian". Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey. Chicago Public Library Omnibus Project of the Works Progress Administration of Illinois. 1942 – via Newberry Library. (English translations of selected newspaper articles, 1855–1938).